A Teenager Photographs the Syrian War

by Leila Nachawati Rego for El Diario (Spain), translated by Joey Ayoub

1 August 2019 (original post in Spanish)

Muhammad Najem, sixteen years old, has spent almost half his life living through and reporting on the Syrian war, sharing on social media his everyday experiences under the bombs. Today he does so from Istanbul, where he fled eight months ago and from where he continues to alert the world about the situation in Idlib and the rest of Syria.

Russian planes have been bombing Idlib, in Syria’s northwest, since the end of April. They do so on a daily basis, and the victims are in their hundreds. On July 22 and 23 alone, over sixty people were murdered and one hundred injured in an offensive that the UN described as the most lethal since the increase in hostilities. Bombs have fallen on markets, universities, and hospitals, and a majority of victims are women and children—many of whom had already been twice or thrice displaced. Idlib, the last place left in Syria outside of Assad’s control, has become host in recent years to people fleeing other areas such as Hama, Homs, and Ghouta.

One of those people is Muhammad Najem, a young boy of sixteen who has spent nearly half his life living through and reporting about the war, sharing his everyday experiences under the bombs on Youtube, Twitter, and Instagram. First he reported from Eastern Ghouta, the suburb outside of Damascus which in August of 2013 suffered the first chemical attack in the country, and a place described by the UN in February of 2018 as “hell on Earth.”

He was only a child when, staring at the camera with his big blue eyes, he shared his first images of the bombings flattening his neighborhood. Since that day, he would record almost daily, prematurely becoming a reporter in a war that has long ceased to make headlines. Today he does so from Istanbul, where he fled eight months ago and from where he continues to alert the world about the situation in Idlib and the rest of Syria.

“Wait, I need to write my ideas to organize them,” he tells me before answering the first questions. “If I don’t write it, everything is very chaotic to me.” He shares with me a large image file, inside of which are photos of demolished buildings and very graphic scenes of the aftermath of bombings, mixed with snapshots of children playing football or orange blossoms—these the photographer shows with pride.

We stop at one photo showing him studying by candlelight during one of the many blackouts in Eastern Ghouta. A very good student since childhood, Muhammad says that since then it’s become harder to study without being close to his sister. “It is especially difficult to learn English, although I know it is very important to study it in order to continue telling the world what is happening in Syria.”

Doubly Displaced

After a few months in Idlib, Muhammad managed to reach Turkey. He was accompanied by his mother and three siblings—four, seven, and twenty-five years old. Qusay Noor, the eldest, is also known for sharing everyday life under siege through his social networks. “It was he who taught me how to record, to do the selfies properly, to open internet accounts,” Muhammad emphasizes. A fourth sibling is eight months pregnant and stayed in Idlib out of fear that the trip would be too risky. Now she regrets not having left immediately and has been trying, unsuccessfully, to reunite with the rest of the family in Istanbul.

“When we were leaving Idlib and saw that we were going to take a plane, we wept with emotion,” recalls the teenager. “My little sister kept asking me if I was sure that this was not the same plane that was bombing us.”

For much of the Syrian population, the countless subjected to years of airstrikes, airplanes are synonymous with bombing. Muhammad has seen them destroy everything they found in their path, razing land and buildings and leaving indelible consequences on their victims, especially the youngest.

“With my photos and videos I have tried to focus on the effect on children,” he says. “During the chemical attack, many children I lived around in Ghouta suffered terrible burns. Years later, they still had disfigured faces. They were burned so horribly that other children were frightened and did not want to play with them. I would stay to play with them and in the end they ended up forgetting everything and smiling. I really liked that feeling.”

He tells of life under siege with raw images showing the population’s suffering mixed with everyday moments of relative normality. He also accompanies these with comments full of sensitivity, tenderness, black humor, irony, and resilience. He shows me a photo in which he is seen eating from a gas stove, surrounded by rubble. The caption reads “Here are the sons of Ghouta. Despite the hysterical bombing, despite the hell of death, despite the lack of life and lack of food and medicine … always smiling.” The hashtag “#Life_In_Graves” follows.

When the situation became unsustainable in Ghouta, Muhammad had fled with his family to Idlib, a place that has received displaced families from across the country. “For a few months we were quite happy there. I liked going to visit families who had just arrived, like us, and who were welcomed by those who were already there, to interview them. Those months, when there were no bombings and Syrians could live in relative freedom, were good.”

The truce which Muhammad is referring to, the one agreed to by Turkey, Russia, and the Syrian regime, did not last. Idlib, located in the northwestern corner of Syria, along with parts of Aleppo and Hama provinces, is controlled by an alliance in which the Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) group, an Al-Qaeda offshoot, is the most powerful. HTS is also responsible for repressing local dissent and using their power to silence those who question their authority.

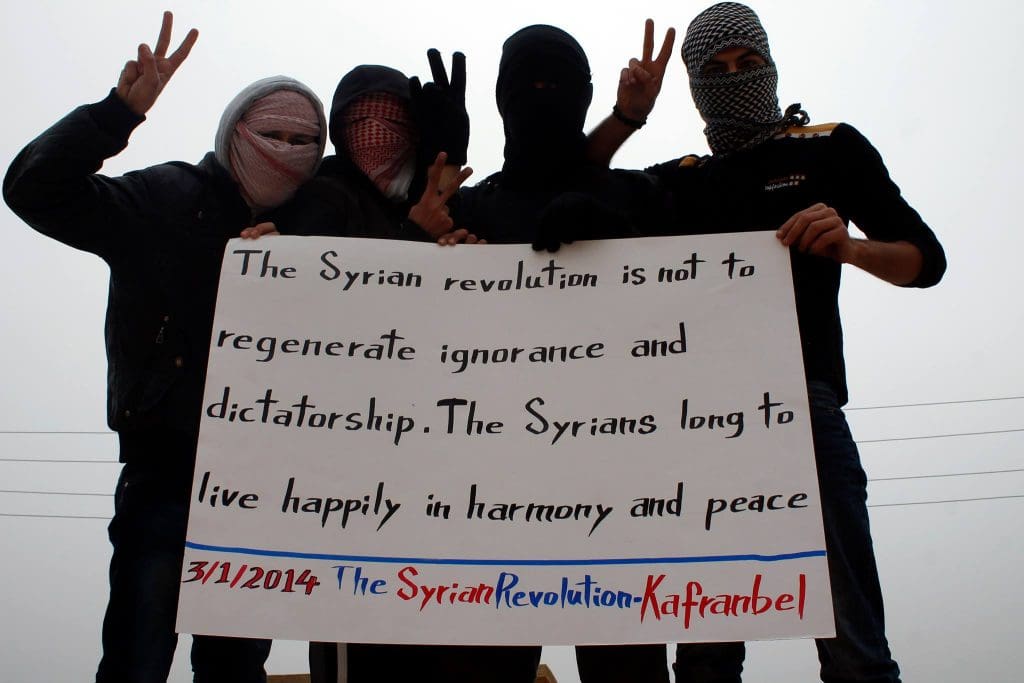

In addition to that group, other activists and opponents from across the country form a complex network throughout the region. This network regularly produces internal tensions between civil activists and extremist groups, and hundreds of people have participated in demonstrations calling for freedom and justice, both against Assad and his allies and against those who try to take their place by destroying the people’s aspirations. In addition to this difficult situation, air attacks have become common over the past three months, progressively constricting the last space beyond the control of the Assad dictatorship.

Speaking with Muhammad, it is easy to notice that, in his sixteen years in which he has seen and experienced things that most do not in a lifetime, he feels indebted to the children who remain within the country. “Now I am safe, but I don’t feel well. I think I should be inside, sharing the fate of the rest of the children and telling the world what is happening and how people live in my country.”

The attention of the world that Muhammad seeks has long since died down, as has the coverage of the tragedies that continue to plague the Syrian population. Those of us who closely follow the situation in the country often hear the question: “But isn’t the war over already?” The truth is that the announcement of the war’s “end,” promoted by Assad and his allies since December 2018, does not recognize the devastation they continue to cause in the north of the country, where they recently bombed a well that supplied drinking water to much of the local population. “The end of the war” also does not acknowledge the increase in torture in regime prisons, a situation that organizations such as Amnesty International have condemned.

People detained and executed in Syria include numerous internally displaced persons, such as the young Tareq Abdul Hakim Kiwan, who defected from the regime army. After a long stay in Dera’a, he had returned to Damascus in the hope of finding relative stability and reconciling with authorities. He was arrested on the spot and died under torture at the end of July, according to news received by his family. Many who have tried to “reconcile” with the regime have met the same fate. Other detainees are people expelled back from countries where they had managed to flee, such as Lebanon or Turkey–they are received by the Assad regime with death sentences.

Muhammad knows of people in Turkey who are being forced to return to a Syria that is not safe for them. He tells me that he does not understand what is happening. “They treat me and the people I know here well,” he says, “but now they say there are many Syrians who are here illegally and must return.”

“Most of us will not be able to return while there is no freedom in Syria,” he adds.

All images reproduced with the permission of the photographers.