Transcribed from the 23 February 2020 episode of The Final Straw Radio (Asheville, North Carolina) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole episode:

Although each country has its own specific situation, there are a lot of similarities: the authoritarian regimes, the corruption, the bad socioeconomic situation. And people are not being silenced. Something changed in 2011, and despite the massive repression these protest movements have faced, something has changed within people. That’s going to have a massive impact on the future. There’s going to be a lot of change happening in the region, and we’re only at the start of that process.

The Final Straw: I’m very happy to be joined by Leila al-Shami and Joey Ayoub. Joey is a Lebanese-Palestinian writer, editor, and researcher; he was the Middle East and North Africa editor at both Global Voices and IFEX until recently, and is co-editor of the book Enab Baladi: Citizen Chronicles of the Syrian Uprising. Currently he is doing a PhD at the University of Zurich on postwar Lebanese society. Leila is a British-Syrian activist and the coauthor of Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War.

Thank you both very much for taking the time to chat with me.

Leila al-Shami: Thank you.

Joey Ayoub: Thank you.

FS: I thought we could talk about anti-authoritarian aspects of popular movements against the regimes in both Lebanon and Syria and for new ways of living, and what solidarity can look like, within that region and from outside, with those popular anti-authoritarian movements. This is a really big conversation, and I’m very excited for the information that y’all are going to present.

First can y’all lay out a thumbnail of the post-colonial development in the respective countries—in Syria and Lebanon—including a bit about the interrelation between those neighboring countries, at least up until those anti-corruption and anti-authoritarian protests known as the Arab Spring?

JA: The primary thing to remember when it comes to the relationship between Syria and Lebanon is that historically they are the same region, “Greater Syria.” With regard to contemporary events, what’s important to understand from a Lebanese perspective is that the Syrian regime was one of two military occupiers of Lebanon—the other being Israel—between 1976 and 2005, when it was essentially forced out after a popular uprising.

Since then, the relationship between the two countries is extremely complicated, to say the least. On the one hand there is a major Lebanese political party that is active in supporting the Assad regime in Syria—I’m talking about Hezbollah. On the other hand, when we speak of Syrians in Lebanon we have to differentiate between the Syrian regime and Syrian refugees. Syrian refugees are effectively powerless and living in pretty bad conditions—I’m phrasing this lightly. It is really bad these days. They are often the victims of scapegoating by xenophobic sectarian parties that have played the same card against Palestinian refugees in the past—they are just using it against Syrian refugees today.

Any relationship is very complicated; there are historical links, but there are activist links as well. But other than that, the two countries are fairly separated due to this power dynamic.

LS: From my side, I think it’s important to understand how the Syrian regime, the current regime, came to power. The Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party came to power in 1963 through a military coup, and it was founded upon an ideology which incorporated elements of Arab nationalism and Arab socialism, both of which were witnessing popular resurgence in the wave of decolonization. Hafez al-Assad came to power in 1970 through an internal coup within the Ba’ath Party. It was under him that the totalitarian police state was built, which repressed all political freedom. Any opposition or dissidents were dealt with very severely under Hafez al-Assad, and what became known as the ‘Kingdom of Silence’ was built. People were not able to express themselves politically.

Bashar inherited the dictatorship from his father in 2000, and when he came to power, Syrians were hoping for an opening—that they would have more rights and freedoms. But really he continued the policies of his father in terms of political repression, and the prisons were full of Muslim Brotherhood members, Kurdish opposition activists, leftist activists, and human rights activists. And there was also a very desperate socioeconomic situation: a wave of liberalization of the economy under Bashar which really consolidated the wealth in the hands of crony capitalists who were loyal to or related to the president, meanwhile subsidies and welfare that the poor relied on were dismantled.

It was these two factors, both the political repression and the very desperate socioeconomic situation, which led to the uprising which broke out in 2011—which of course arrived in the context of this transnational revolutionary wave that was sweeping the region.

FS: I think a lot of people in the West get confused with the term socialist in the expression of Ba’athists, and don’t have a specific understanding of what that term means in that instance. Can you break it down for those of us who are confused about what socialism refers to in terms of Ba’athism?

LS: The Ba’ath Party advocated socialist economics, but rejected the Marxist conception of class struggle. The Ba’ath believed that all classes among the Arabs were united in opposing capitalist domination by imperial powers, proposing that nations themselves, rather than social groups within and across nations, constituted the real subjects of struggle against domination.

So when they came to power, they pursued top-down socialist economic planning based on the Soviet model. They nationalized major industries, and engaged in large infrastructural modernization to contribute to this nation-state building enterprise: redistributing land, erasing the land-owning class, and improving rural conditions. It was these kinds of populist policies which brought the party a measure of cross-sectarian public support.

But at the same time, leftists were purged from the Ba’ath Party right at the beginning. Hafez al-Assad’s coup within the Ba’ath Party was against the leftwing faction. And later, all left opposition was either co-opted or crushed. Independent associations of workers, students, and producers were repressed, and para-statal organizations said to represent their interests emerged—a kind of corporatist model.

And like I said, under Bashar there was an increasing liberalization of the economy; it really moved away from any kind of socialist economic model towards a model which created a great deal of wealth disparity within the population.

FS: Joey, I wonder if you could set up how, after the civil war and occupation in Lebanon, power was distributed through the state structure there.

“All of them means all of them.” It’s very simple. Every single politician that has participated in this postwar status quo has to go. It’s a complete rejection of every single political leader of the postwar era, basically, whether they are currently in government or not.

JA: It’s been thirty years since the end of the civil war. The postwar era, as we call it, started in 1990, when the civil war officially ended with the signing of the Taif agreement—Taif being the city in Saudi Arabia where they signed it. So it’s been almost exactly three decades since then.

The postwar era is defined by a number of things. The primary two components relevant to what is happening today are the format in which this so-called peace happened, and what happened after that. The format can be symbolized through an amnesty law that was passed in early 1991, which pardoned most crimes which were committed during the war—the only exception being the killing of other important people. If you had assassinated a prime minister or something like that, you might be exempted from the amnesty law. Other than that—if you were involved in kidnappings, enforced disappearances, torture, murder, all of these things—all of your crimes were wiped clean overnight.

Warlords who made their names during the war became the warlords who entered government in the nineties. They removed their military uniforms, put on their business suits, and became the government. The people we’re dealing with today for the most part are the exact same people who were the warlords during the civil war. The two very easy examples I can give are the current president, Michel Aoun, who was a warlord in the eighties, and the speaker of parliament, Nabih Berri, who was also a warlord in the eighties.

These people have each created clientelist networks—we call it wasta in Arabic—and the result is we don’t really have one state. We do in theory—but that state is subsumed within these sectarian networks.

The second thing that happened in the postwar era which is also important is what you might describe as actually-existing neoliberalism. There was a rabid form of capitalism, the “shock doctrine” scenario that Naomi Klein famously coined in her book, wherein all the ruins of the war were further demolished. The most symbolic example of that is downtown Beirut, which saw a lot of the violence. Large parts of it were completely demolished instead of being renovated and public spaces being made accessible again, and everything was privatized.

Fast forward three decades: what we’ve been seeing since October 17, 2019, this symbolic date when the current uprisings started, are attempts by a number of protesters to reclaim this public space that has been privatized, and to reclaim a sense of identity that transcends these sectarian limits which were implemented in the postwar era.

They were always there—they have been part of Lebanon’s de facto legal reality. Sectarianism is institutionalized. Political confessionalism is the official term for it. In the postwar era there have been quite a lot of protest movements trying to move beyond sectarianism, calling for some kind of secularism, some kind of trans-sectarian identity, with the knowledge that sectarianism isn’t just a social ill in itself (as in, it’s bad to be sectarian) but also understanding that sectarianism is used in a specific way in Lebanon that benefits those who are already at the top.

That’s a simplistic summary, of course, but that’s essentially what we’ve been seeing since October 17. And this time there is a momentum that is explicitly anti-sectarian, and an awareness that as soon as sectarianism wins, the movement immediately loses. There’s an extreme sensibility towards remaining anti-sectarian.

FS: Would you mind talking a little bit about how the clientelism and expectations of social infrastructure, and the lack of following through on these expectations, led to the October protests, and how clientelism stands in opposition to the idea of a social contract?

JA: It is very difficult in Lebanon to do anything unless you have the connections. Education, healthcare, basic services like electricity and water—people tend to rely on private networks for all these things. I went through a private education. Most people in Lebanon have to pay two electricity bills, one private and one public, because the public one is not 24/7. For water, technically you pay three different bills, because there’s public and private running water, and separately there is bottled water because the tap water is not potable. This is a small example of how the clientelism functions in Lebanon.

It really precedes the civil war, and going all the way into that would require a different kind of analysis which I’m not the most capable of giving. But what we saw in October—and in the months and years preceding October 17—was this lack of social contract becoming even more painful. Before then, there was always a way for a percentage of the population—I can’t even say for sure it’s a majority—to sort of get by. There was always a way to make ends meet, so to speak, one way or another. Living conditions were never extremely good, but they were decent enough for you to have an okay life. Especially, obviously, if you’re middle class. That has declined in the last decade or so.

The 2011 uprisings had an impact on Lebanon. Cutting off Syria economically from Lebanon impacted business locally. It also reduced significantly any kind of Gulf investment, which had been reliable up until 2011-12. That’s what has been breaking down slowly in the last decade, and that’s part of the spark that led to October 17, 2019. But that week, that same week, there were very bad wildfires that ravaged through the country and even reached parts of Syria; it was over forty-eight hours before they were fought off through a combination of luck—it started raining—and airplanes that were donated by foreign governments.

And just a day later, the government decided to impose a tax on WhatsApp calls, which are obviously free and used by virtually all Lebanese because actual phonecalls are so expensive due to the corruption and clientelism. That was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

On the night of 17 October, the day the WhatsApp tax was proposed, people spontaneously went to Beirut, to Nabatiyeh in the south, to Tripoli in the north—people went out in cities across Lebanon. In the first couple of weeks, the momentum was so overwhelming. It was on all levels across all regions of Lebanon, with almost no exceptions, touching all socioeconomic classes (there were even protests where I live; this has never happened before), and there was a very explicit anti-sectarian component.

When the 2011 uprising happened in Syria, it was a broad-based, inclusive movement. It included many women from all different backgrounds, a diversity of Syria’s religious groups and ethnic groups, all united around the demands for freedom, for democracy, and for social justice.

This is remarkable because sectarianism in Lebanon has created a reality where it is virtually impossible—in practice it just never happens—that if you are from a certain region and you’re just used to seeing people from a certain sect (with the exception of the big cities like Beirut), you don’t really know much about other parts of the country where a different sect has a majority. If you come from Mount Lebanon you don’t necessarily know much about the south or the north, unless you have family connections.

That’s been our reality for three decades. And nonetheless in the first month or so, it was very common to see people in Tripoli (the Sunni-majority city in the north) sending their solidarity to Nabatiyeh (the Shia-majority area in the south) and vice versa. In Jounieh (which is Christian majority) and Beirut (which is very mixed) and Mount Lebanon (which is Druze majority), there were always explicit statements of solidarity from one region to another, from one sect to another, saying, essentially: we have this thing that unites us beyond our sectarian allegiances.

The other extremely important component is summarized by the chant kelon ya’neh kelon, which means “All of them means all of them.” It’s very simple. Every single politician that has participated in this postwar status quo has to go. It’s a complete rejection of every single political leader of the postwar era, basically, whether they are currently in government or not.

That’s very important, because there have been a number of sectarian parties that were previously in the government and currently are less so—they still have MPs but they are not the ruling parties—that have been trying to ride the wave of the revolution by presenting themselves as opposition parties, trying to play with the binary that is the March 8 and March 14 movements.

What are these two? March 8 and March 14 are the names of two coalitions that were formed on those dates in 2005. Following the assassination of then-prime minister Rafic Hariri on February 14, 2005, there were mass mobilizations on these two dates with different orientations towards the Syrian regime. On March 8 was the pro-Syrian regime protest, led by Hezbollah and Amal at the time. On March 14 was the anti-Syrian regime protest, led by the Future Movement, the Lebanese Forces, the Phalangists, and the Progressive Socialist Party and other parties. Since then they have created a power-sharing agreement following the model of the postwar era, where it’s one coalition or the other that’s ruling, always fighting with each other but always finding more things in common than things that distinguish them—especially when there are independents trying to run against both of them, that’s when they close ranks.

Because the current government, for various reasons, is a March 8 government—Hezbollah, Amal, and the Free Patriotic Movement—there are parties that were traditionally associated with March 14—the Future Movement, the Progressive Socialist Party, the Lebanese Forces, and the Phalangists—that have been trying to place themselves in the position of opposition against the March 8-led government.

The protesters are rejecting that. No. All of them means all of them; you will not be able to ride the wave of the revolution. In five days it will be the four-month anniversary of these protests, and the momentum has changed, but it is still firmly anti-sectarian.

FS: Let’s turn and rejoin Leila in the chronology of how anti-corruption movements had been developing in Syria and then come back to anti-corruption in Lebanon. Leila, Joey had mentioned Syrian refugees being present and the way the forest fires crossed the border; these two countries have had a lot of interaction between each other. I’m wondering if you could talk about how the anti-corruption and reform movements and revolutionary movements of the Arab Spring effected and impacted Syria, with the Syrian revolution and subsequent civil war.

LS: People in Syria were generally quietly against the regime prior to 2000. The last major uprising had been at the end of the seventies and beginning of the eighties, and started off as a broad-based movement against the regime but ended up becoming very dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood due to the severe repression of those who were participating in it. It culminated in the massacre of Hama, when thousands of people were killed and much of the old city of Hama was destroyed by Assad’s forces. In addition to that, thousands of people disappeared into regime detention; many of them were never seen again. This experience of such brutal repression had kept Syrians quiet since that time.

But when the Arab Spring, as it came to be known in the West, emerged in 2010-11, people in Syria were seeing what was happening in Egypt, what was happening in Tunisia, and the governments being brought down there, and they began to ask, “Why not us?” This gave people—a new generation that hadn’t directly experienced the repression that had occurred before—the strength to go out onto the streets and start demonstrating themselves. Unlike Tunisia and Egypt, though, people in Syria didn’t go out into the streets calling for the fall of the regime, initially. What they were calling for was reforms: things like a multi-party system, the release of political prisoners, a free press.

These were demands which had been taken up in 2000 when Bashar first came to power, and people thought there was an opening for change. There was a small movement—it wasn’t a popular broad-based movement like we saw in 2011, but it was a movement among intellectuals and human rights activists that started to call for reforms when Bashar came to power. That movement, again, was severely repressed, and all hope for change under Bashar died at that point—until 2011, when what happened in Tunisia and Egypt really reignited the hopes of a new generation.

So they came out onto the streets calling for reform, but the brutality of the response by the state—which immediately began meeting peaceful, unarmed pro-democracy protesters with gunfire, massive waves of detention, and repression—radicalized the movement. It caused it to spread rapidly across the country, and it encouraged people to start calling for the fall of the regime and even for the execution of the president. It was the regime’s repression which really catalyzed the movement’s spreading and becoming a revolutionary movement.

I think it’s very important to recognize that when this happened in 2011, it was a broad-based, inclusive movement. It included many women from all different backgrounds, a diversity of Syria’s religious groups and ethnic groups, all united around the demands for freedom, for democracy, and for social justice. The social justice element is often not focused on very much in the West. But it was a large component of the revolutionary demands.

Many people went out on the streets and chanted against the crony capitalists who had amassed a great deal of wealth under the current regime. For example, Rami Makhlouf, who is Assad’s maternal cousin, was estimated prior to 2011 to control some sixty percent of the Syrian economy through his business interests—in real estate, mobile telephone companies, etcetera. There were large chants against him on the streets and against other crony capitalists.

There was a strong element of awareness and strong social and economic demands as part of the revolutionary movement, but those were not focused on very much in Western reporting.

While the organized resistance movement and organized civil society has been very much crushed over recent months as the regime has taken control, we see that the desire for freedom, for justice, for this regime to end, has not gone away.

FS: In your book Burning Country that you coauthored, y’all made a point of saying when people took up arms to defend themselves against the government, the inclusivity of the popular movement started to dissipate. That’s how I remember reading it, at least. Can you talk about what the integration of armed struggle into the movement against the government did to the dynamic of the revolution, and how it became a civil war?

LS: Taking up arms was a response to the massive repression by the state against peaceful protesters. At the beginning it was still inclusive—this wasn’t an organized military or army. This was people taking up weapons in their communities to defend their communities and their families from assault. People were being taken from their homes and detained; there was also a mass rape campaign carried out in oppositional communities by Assad-affiliated militias. So people took up arms to defend themselves in loosely-coordinated defense brigades.

By the summer of 2012, we started to see the Free Army label being used. Now, the Free Army was never really an organized army; it was never centrally controlled or centrally funded, although there were failed attempts to do so. It was an umbrella which different groups and different militias could come under with two main aims: one was the fall of the regime, to force Assad out of power, and the other was to see some kind of democratic transition take place. The people who signed up to the Free Army label were people who were united behind those aims.

But as time went by, the armed opposition became more and more fragmented, due to external pressures on them. They couldn’t get the weapons that they needed to really defend themselves and their communities from regime assaults. There were light weapons going in, but the anti-aircraft missiles which people desperately needed were not being provided. Aerial assaults were the main cause of destruction and main cause of death, and it was Assad who was controlling the skies—later alongside his Russian ally.

We also saw, around December 2013, an increasing Islamization among armed groups in Syria. The main reason for that was the failure of the democrats of the Free Army to attract funding and support from the Western states that they were reaching out to. Some brigades started Islamizing their rhetoric in order to attract support from Gulf donors specifically.

So there was an increasing Islamization of the opposition groups, and an increasing fragmentation of armed opposition groups. There were so many different armed brigades that were present at that time, and we see now that most of the armed groups operating in Syria do have an Islamist leaning and have eclipsed in strength the democrats of the Free Army.

But while there was this fragmentation of the armed opposition—which was due in large part to this competing struggle for weapons, competing struggles for military dominance and political dominance in areas they were controlling—there was also, in parallel, a continuing civil movement which was committed to the original goals of the revolutionary struggle and remained an inclusive and diverse movement.

FS: Fast-forwarding now into what has been nine years of one of the most deadly civil wars of the twenty-first century so far, I’m sure what a lot of people are experiencing on the ground in opposition areas at this point is simply a struggle for survival against this genocidal regime. But can you say anything about what exists, as far as you’re aware, of democratic movements for social justice in Syria?

LS: There are plenty of Syrians who are still committed to those ideals of the revolution, and there are plenty of Syrians working today within their communities trying to keep things functioning; plenty of civil society organizations that are continuing to do media work, continuing to assist the displaced, trying to keep hospitals functioning. But it has become a matter of survival, a struggle for survival. Today the main area which is outside Assad regime control, or still in the control of rebel groups, is Idlib. Idlib today is facing an absolutely relentless assault, a war of extermination against the civilian population there.

Since the assault on Idlib began in April 2019, over a million people have been displaced, nearly 700,000 since December alone—just gone. There have been massive attacks on civilian infrastructure; dozens of hospitals put out of action. People are fleeing for their lives. It’s very hard in such circumstances to talk about any kind of organized movement, because people are really just struggling to survive. People are fleeing outside of Idlib city or to the north of Idlib, and there’s no place left to go, no remaining safe haven for people. Many of these people had already been displaced multiple times, when their communities came under attack or were forced to surrender and recaptured by regime forces. And the borders are not open. The situation on the ground today in Syria is completely desperate.

In areas that have come back under regime control, whether we’re talking about Dera’a in the south or the Ghouta around Damascas, there have been massive waves of repression against the population who stayed. Anyone who is seen to have been in any way affiliated with the opposition has been arrested and detained. Young men have been rounded up and sent to the front lines to fight, basically on missions from which they are not going to return.

But we have also seen that resistance has continued. There have been waves of protests happening in Dera’a. Extremely courageous people in regime-controlled areas have still been protesting, calling for things like the release of prisoners, protesting against the desperate economic situation. Just in the last couple of weeks in Sweida, which is a Druze-majority area, people have been out on the streets protesting against a very desperate economic situation, protesting against the corruption they’re seeing.

In Dera’a, we’re seeing waves of assassinations against regime forces as well. So while the organized resistance movement and organized civil society has been very much crushed over recent months as the regime has taken control, we see that those desires for freedom, for justice, for this regime to end, have not gone away. And when others have a chance to organize, they’re still trying to organize—they’re very clear that they’re not going to accept this regime. There’s no life for people under this regime.

If I want a society that is better than the current society, I have to face the contradictions of that society. Those contradictions, whether we’re talking about sectarianism, xenophobia, nationalism—all of these things exist everywhere in Lebanon. They exist within your own family, within your community networks. It is very difficult just to say, “Screw all of you, I am going to create something without all of you.”

FS: This is a subject that I’m sure gets brought up a lot in conversations about Syria with Westerners, but it seems like the democratic social movement had a few different fronts on which they were being attacked, including with the uprising of Daesh as a movement across Iraq and Syria. In your experience, is Daesh still a threat against social movements, or has it been crushed, as it’s been presented in the Western media?

LS: Daesh hasn’t been crushed. There’s this idea that you can defeat an ideology militarily when the conditions that fed that ideology are still very preset, when the chaos which allows such extremist groups to thrive is still there. Daesh has certainly lost a lot of its organized power, but it has the ability to regroup and re-form—we’ve seen that in Iraq, and in attacks that have been carried out in Syria in recent months.

It’s not just Daesh which is a threat. If we look at Idlib—I said that Idlib was the main province still under rebel control. The group in control of a large part of Idlib is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, formerly al-Nusra, which is a very extremist Islamist militia. They have repeatedly tried to wrest power away from the democratic opposition structures which were established in Idlib following the liberation from the regime, and have tried to impose their own extremely authoritarian religious strictures upon a population which overwhelmingly rejects them.

This is something which is not spoken about much in the West. People often say Idlib is an “al-Qaeda enclave” because this group HTS was formerly affiliated to al-Qaeda. What they’re overlooking is all the people protesting against the group. We’ve seen continuous demonstrations in Idlib, up until now, people calling for HTS to leave their communities and hand over power to democratic opposition structures.

So yes, Syrians have had a battle on two fronts. They’ve had a battle against this fascist tyrannical regime which is committing genocide against a population which demanded freedom, and a struggle against extremist Islamist groups such as Daesh and HTS and others.

The third battle, of course, has been against people in the West, often people who identify as being on the left, who have continuously slandered revolutionary Syrians, have equated revolutionary Syrians with groups like al-Qaeda, and have in fact thrown their support behind the Assad regime. Free Syrians have found that they have very few friends. But they retain their desire for freedom, and they continue to maintain that they are not going to accept one tyranny being followed by another.

FS: Joey, on an episode of the Arab Tyrant Manual from November 2019, you and another guest, Timour Azhari, were talking about calls for solidarity with the Syrian people that were coming up in the chants of Lebanese protesters, and I wonder if you, or both of you, could talk a little bit about solidarity against authoritarian structures across that border, between Lebanon and Syria, and between the popular mobilizations against sectarianism that you’ve seen.

JA: The anti-sectarian component of the protest movements in Lebanon essentially appeals to some kind of national identity. It’s one thing to have my religion as a Christian, as a Shia, as a Sunni, as a Druze, and that’s fine, but there should be something that unites us further than that—we’re all Lebanese. Of course that’s a double-edged sword: nationalism can unite people across sects within one nation-state, and it can also otherize people who are not Lebanese.

That’s a very common thing, and it’s a reality that anti-authoritarians, progressives, radicals, lefties, and others in Lebanon have to contend with: the overwhelming presence of xenophobia. Much of it was created during the civil war; the Syrian regime was an occupier, so many Lebanese, especially those of the older generation, equate Syrians with the Assad regime. This is very ironic and self-defeating, because obviously Syrian refugees in Lebanon are fleeing a conflict that was started by the Assad regime; there could have been opportunities for cooperation and unity. But what is happening is xenophobia and nationalism.

In the same way as in Hong Kong, where there is a segment of the population which is anti-China in the ethnic sense rather than being anti-Chinese-government, there is in Lebanon a segment of the protesters that is anti-Syrian, not just anti-Syrian regime. There are even Lebanese who oppose the Syrian regime, who oppose Hezbollah, who still share the same xenophobic, racist attitudes towards Syrian refugees.

And this power dynamic is worsened by the fact that the economic situation in Lebanon is already shit. It’s really bad. It creates the opportunity for scapegoating Syrian refugees, modeled after the scapegoating of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon since the Nakba: they faced this type of attitude, especially during the civil war because there was an armed Palestinian faction, but that’s a different story.

To try and counter that, there is a segment of Lebanese protesters, most notably the feminists, who are trying to create a movement that is more inclusive. They are openly intersectional and speak about class struggle, and about gender equality beyond the confines of citizenship—which is already very restrictive in Lebanon. You cannot become Lebanese other than by marrying a Lebanese citizen or inheriting it—and even then it is only passed on by a man. You can inherit citizenship if your father is Lebanese, but you cannot inherit it if only your mother is Lebanese. So there is a percentage of the population in Lebanon that are “not even Lebanese” but who are in fact Lebanese. What the progressives are saying is that if someone can be Lebanese and not Lebanese at the same time, we can also accept that there might be more than one way of being Lebanese. This is why I insist on calling myself Lebanese-Palestinian, to refuse to relinquish my grandfather’s identity. It’s not even considered something that can be a reality. You’re either one or the other, and that’s it.

Something being called a “revolution” or having revolutionary momentum does not automatically mean that everyone participating in that uprising has the best politics in the world. Even in Syria in 2011-12, there were conservatives who would take part in the protests. That’s completely normal. There’s more than one way of expressing opposition to illegitimate authority. If we’re talking about the Assad regime, there are multiple ways of opposing it. There are even Islamists who oppose the Assad regime. As a progressive who would not want to have an Islamist regime either, you still can’t automatically reject everyone who doesn’t share every single one of your politics. It’s complicated.

In Lebanon it’s complicated in different ways. In the beginning, there were sectarian people participating in the protests. There were members of Hezbollah, members of the Lebanese Forces, and members of other sectarian political parties among us. Even to this day, there still are, but to a lesser extent. They were in fact going against their own parties, without renouncing their parties. What happens in that space, within that momentum, is a sort of negotiation. Chanting kelon ya’neh kelon made lots of people uncomfortable. Calling out certain specific politicians by name made certain people uncomfortable. That alienated some people, whereas other stuck around. Some people were “converted.” Other people still participate without chanting these specific chants.

So there’s an ideal: kelon ya’neh kelon, anti-sectarianism, a vision of a fair society. And within that ideal, there are multiple ways of negotiating, because at the end of the day, if I want a society that is better than the current society, I have to face the contradictions of that society. Those contradictions, whether we’re talking about sectarianism, xenophobia, nationalism—all of these things exist everywhere in Lebanon. They exist within your own family, within your community networks. It is very difficult just to say, “Screw all of you, I am going to create something without all of you.”

The first and most important aspect of solidarity is correcting the information. There is so much disinformation circulating about what is happening in the region. It’s so exhausting for activists who have much more important struggles than focusing on correcting the narrative. It would be great if some of that work could be done from the outside.

FS: Leila, the reason I first heard your name besides Burning Country was in reference to Tahrir-ICN coming up in the 2010s. Can you talk a little bit about that project and what became of it, how it developed, and what impacts you saw it have?

LS: Tahrir-ICN was an attempt to address the issue of a lack of knowledge of anti-authoritarian struggles in the region, outside of it. A group of activists came together, myself included, with the idea to build this network among anti-authoritarian activists in the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. It had two components to it. The first was an information-sharing platform, establishing a blog and social media accounts. The second was to build a physical network where we could work on practical actions and build solidarity together, sharing experiences.

The first aspect of it was quite successful. It started in 2012, just after the revolutions in the region broke out. Different collectives from across the region and in Europe started sharing information of what was happening in their country. This was a time when there were lots of uprisings across the region and also in Greece and in Spain: the Occupy movement, a lot of exciting things were happening. It didn’t have one vision. It was trying to learn from a wide variety of experiences and struggles loosely labeled anti-authoritarian. We had quite a wide readership for our blog, and I think it was very useful for people outside, in Europe or in America, to find out more about anti-authoritarian struggles in the Middle East and North Africa, and vice-versa..

The second aspect, building a physical network—we had a number of discussions about having an event to bring people together. There was certainly a lot of interest in that. But then the counterrevolutions broke out very strongly. People became very bogged down in what was happening in their countries. People started losing a lot of energy, and the network kind of fizzled out. I myself decided that I had to prioritize what was happening in Syria due to my connections with Syria. People got very caught up in their own stuff, and it kind of died out. But I think that for the time when it was operative, it provided a useful source of information to learn about each other and to see the wide variety of struggles that were occurring.

FS: For the sake of us staying informed and educated about what’s actually going on in this region of the world, can y’all talk about maybe some resources that we have, particularly in English, that we could be relying on to get a better grasp? And also maybe some resources that you think are trash and we should avoid? That would be very helpful.

LS: I would encourage people to look for resources which are produced by people who are living in or connected to the regions themselves. It’s very important to try to go to native sources where possible, to people who have a very real understanding of the issues because they’re directly affected by them. We’ve been very privileged that there is so much information available in English. There are so many activists who are very active on social media across the region who we can connect with on Twitter, on Facebook, who are telling their stories. From Syria, there are so many great independent media initiatives. There is Enab Baladi—Joey worked on producing a book of some of their texts—which was established by women in one of the main revolutionary towns known as Daraya. There were some amazing experiences of self-organization in that town. There is al-Jumhuriya, which was established by Syrians, which is great for analysis of the region.

I would encourage people to find out a bit more and to go to these sources, and to try to educate themselves. The first and most important aspect of solidarity is correcting the information. There is so much disinformation circulating about what is happening in the region. It’s so exhausting for activists who have much more important struggles than focusing on correcting the narrative. It would be great if some of that work could be done from the outside. It would certainly free up Syrian activists to focus on other more practical things that they need to address.

JA: On the Lebanon side of things, I can start by recommending a podcast that’s called The Lebanese Politics Podcast. Starting with the episode which was released just after the October 17 revolution started, they’ve put out about an episode a week, in English, in which they go back to the events of that week and interpret them and talk about them. It is as objective as you can get, from an archival perspective. Both of them are on the left and are analyzing from the anti-sectarian angle.

Other than that, most good media in Lebanon is in Arabic. Recently, especially since 2015 when there was another uprising—which was not as successful but laid the groundwork for what was to come—there were things like Megaphone News, which is mostly in Arabic but sometimes has English stuff; they are really good. There is the Public Source—again, these are mostly in Arabic but occasionally have some English stuff.

A lot of the voices of anti-authoritarian Syrians are present in mainstream Anglo media. Just recently there was For Sama, the documentary that was nominated for an Oscar and won many film festival awards. There was the White Helmets documentary from 2017. There are a bunch of really good war-related but more personal-narrative documentaries popping up. All of these are available with English subtitles, and are very easy to find these days.

The main thing to challenge, really, is disinformation. The decision is whether people want to believe what they are seeing with their own eyes. For Sama is literally just footage put together to tell a story. You can think whatever you want, but if you’re starting to doubt what you see with your own eyes, the bombing that you’re literally seeing in front of you, then we’re entering a world that has not just implications for Syrians and Palestinians and Lebanese and others, but indeed implications for everyone else.

Privilege is a responsibility. Having privilege means you should do something with it. Use the access to knowledge that you have and inform yourself on what’s been happening in Syria, especially since 2011, or since 1982, or wherever you want to start, instead of just getting stuck in these echo chambers which have been so common, unfortunately, with the Western left.

The election of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote and the so-called wave of far-right populism (which is a nice euphemism for fascism a lot of the time) didn’t really surprise a lot of us who live on this side of the world and have been involved with anti-authoritarian politics. Some of the signs that we were going into a dangerous international moment were already present in Syria as early as 2013, with the chemical massacre in Eastern Ghouta, among other things. The reactions to that started signaling that we’re slowly moving towards a normalization of blatant violence against civilian bodies.

What progressives in Lebanon are trying to do right now is create a different media landscape outside the norms, a counternarrative to the dominant narratives in Lebanon, because they are very influenced by the sectarian status quo. Many of them are owned by the sectarian parties. With Syria it was very different at first, because there wasn’t really any independent media before 2011. But an explosion of creativity came after 2011 (Enab Baladi, the project I worked on, is one of the examples of that), so now it is very easy to get very decent, advanced, sophisticated information. The question is how much energy people are willing to put into it.

It’s always good to inform yourself as much as possible about what’s happening in the rest of the world, just as a general rule, and there tends to be enough information these days. But the other thing is calling out disinformation when you see it online. To do that convincingly, you do need to arm yourself with quite a lot of knowledge, because the disinformation campaigns, especially since Russia decided to intervene militarily in Syria, have been pretty extraordinary. We’re not just dealing with RT and Sputnik. There are horrific takes being taken for granted which if they were on Palestine would be the abode of the far right, but for some reason when it comes to Syria, lots of lefties repeat basically the same things that rightwing Zionists would repeat on Palestine—the same takes! They just go with that narrative instead of looking at the facts on the ground and reading the books by Syrians who have been writing for decades now, many of whom are translated into English.

Information is power, and it can be used for good. But we have to deal with all of the disinformation around us. It’s been exhausting. Many of us have experienced months of burnout. Most activists I know, including those who were in Aleppo until recently, or in Ghouta or in Idlib or in the south or wherever, have completely given up on trying to challenge anyone online, or are just working locally. Some still spend entire days sometimes arguing with mostly Westerners online about their own country and their own homes that they just had to leave.

Westerners are not going through fascism in the same sense that Syrians are. There is definitely that threat, especially these days, but it’s still not at the level of the Assad regime controlling everything and dropping barrel bombs, and having foreign militaries invited into your country. I don’t know how to say this, but privilege is a responsibility. Having privilege means you should do something with it. Use the access to knowledge that you have and inform yourself on what’s been happening in Syria, especially since 2011, or since 1982 with the Hama massacre as Leila mentioned, or wherever you want to start, instead of just getting stuck in these echo chambers which have been so common, unfortunately, with the Western left.

FS: I’m wondering if either of you have the energy to talk really briefly about that or touch on some of the conspiracy theories we need to challenge? You don’t have to answer if you don’t have the energy.

LS: Very briefly, the White Helmets are volunteer first responders, men and women, people who are often the first on the scene to assist victims of Assad and Russia’s aerial bombardment, taking bodies from the rubble, taking people to makeshift hospitals for treatment. I think it’s because they are first on the scene to record and witness these state crimes that they have come under vicious attack. A lot of the assault on the White Helmets does originate in Russian state media; the Russian state has carried out a massive disinformation campaign against the White Helmets. We’ve seen them being accused of being al-Qaeda operatives; we’ve seen them being accused of being behind chemical weapons massacres. There have even been reports that they are engaged in organ harvesting. All sorts of horrendous and malicious accusations have been thrown at them.

The problem is that a lot of these accusations, which are starting in Russian or Syrian state media, are then being propagated and spread by people who identify as being on the left. We’ve seen a lot of these disinformation campaigns carried out by purportedly leftist activists, and these kinds of conspiracies also find their way into the mainstream. It’s very difficult now to even mention the White Helmets. I spend quite a lot of my time traveling and giving talks about Syria, trying to build solidarity for Syria, and even when I come across people who are generally sympathetic to what I’m saying—they’re not supportive in any way of the Assad regime; they seem to want to stand in solidarity with free Syrians—they’ll come up to me at the end of the talk and say, “Well, what about these White Helmets? We’ve heard this, we’ve heard that.” So this campaign of disinformation has been very successful in polluting the public space in such a way that really makes any kind of practical solidarity with revolutionary Syrians almost impossible.

It’s so dangerous at the moment in a place like Idlib, where international aid agencies have all pulled out. We’re seeing massive targeting of residential infrastructure and survival infrastructure—hospitals, schools, water supplies. It’s the White Helmets who are there, who can provide any kind of lifeline to people who are facing that kind of assault. They are maligned and slandered, when they are really the people who we should be standing behind and supporting—they are in desperate need of funding to continue their work. It’s very difficult to constantly face these kinds of attacks.

JA: Russia’s online disinformation campaigns have been widely studied by now. The discourse that Russia appeals to, or that pro-Assad or pro-Hezbollah folks appeal to, is identical to the War on Terror narrative that was popularized by George W. Bush in the aftermath of 9/11. The whole “You’re either with us or the enemy” mentality was literally almost quoted verbatim by Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, just a few weeks ago. This discourse has been reinforced and rendered hegemonic in some circles of the broader left, especially (but not just) the Western left. Russia has an obvious interest in people believing that the White Helmets are terrorists, because under the War on Terror, terrorists are fair game. You can shoot them. It’s really that simple.

The Russian embassies on Twitter (some particular embassies, like the one in South Africa, have a particular notoriety for some reason) post disinformation against the White Helmets, and against the documentary about the White Helmets—they posted a photo of Osama bin Laden receiving the Oscar. All of these things are Islamophobic smears that have been widespread especially since the aftermath of 9/11. Russia has utilized this in the past, in Chechnya. Chechnya is particularly important to mention here because one of the Russian embassies also tweeted at one point some years ago, during the fall of Aleppo, a before-and-after picture of Grozny—eradicated by Putin and rebuilt—and the message was, “This could be Aleppo.”

One of the untold stories of the Syrian revolution is how in the absence of the state, when the state collapsed or was pushed out of the majority of the country, people came together and began to build alternative structures for self-organization within those areas.

If those among us who call ourselves anti-authoritarians do not understand the consequences or the connotations of this, then we’re basically saying that we do not really care about groups of people that are vulnerable in our own societies, let alone in other societies or in the wider world, including Syrians in this case. The disinformation campaigns don’t just tell you something—they also tell you what not to think. Nothing is True and Everything is Possible. It’s that sort of mentality. It stays in the back of your mind, it just festers there, and that alone is enough to reduce any momentum towards solidarity. What it does is discourage people from looking further.

That is the success of the disinformation. You pollute the media sphere. If you just google the White Helmets, on the first pages you will find a lot of horrible things being said. If you go on Twitter it’s dominated by Russian disinformation campaigns. When I say Russian disinformation I don’t just mean RT and Sputnik, but anyone who hovers around that world. That is extremely dangerous in a situation where these people are literally being murdered as we speak. They have even been targeted by al-Qaeda. Calling them al-Qaeda is not just a horrific, racist, Islamophobic smear—it actually puts their lives in danger.

FS: We haven’t really touched on the Syrian diaspora. I didn’t think about how a lot of this conspiracy theory stuff plays into the rightwing xenophobic rhetoric about people escaping the civil war there or escaping war in Libya or other parts of the world that the West often views through an orientalist and Islamophobic lens: that they are bringing this contagion of terrorism with them or whatever.

JA: Leila’s coauthor Robin Yassin-Kassab observed that before Syrians arrived on the shores of Fortress Europe and were being demonized by the far right as terrorists and demographic threats and all of these slurs, they were already being demonized and treated with hostility by large segments of the left. That scapegoating was already there—it’s not just that suddenly Syrians started appearing in Europe and there was massive reaction against them by the right. Of course there was that as well. But the stories of Syrians arriving in Europe (most are not in Europe, obviously; they are in Lebanon and Turkey and Jordan and so on) were canceled, deleted, smeared, and demonized in advance, accelerating the process of dehumanization.

Understanding what’s happening, the context of a country, especially one in “conflict” like Syria, also means supporting the refugees that come to your shores.

FS: A lot of the coverage that this show has done on war in Syria has been specifically focusing on the struggles in northern Syria, particularly as relates to the Kurdish-majority areas and the PYD and the PKK-affiliated Kurdish movement. This is partly because there’s a better infrastructure for communication and discourse in the West, but also a lot of anarchists and leftists have been for a long time in very active solidarity with PKK-related struggles.

Leila, as someone who’s covered the war in Syria and the revolution before that, could you talk a little bit about how the PYD has related to that?

LS: That struggle has certainly gained much more solidarity in the West, and you touched on the reasons for that: the Kurdish diaspora in Europe and the US has been there for a long time and has been able to build solidarity networks that take a long time to build, and Syrians living in other parts of the country had not had that. They didn’t have so much connection with the West. It’s very difficult, obviously. Even prior to the revolution it was difficult for Syrians to travel, to get visas, to be outside. So there wasn’t that much exchange built up for people to know what was happening in other areas.

Some of it also comes down to a Western orientalism that often likes to focus on minority groups as being the most persecuted, combined with Islamophobic racism towards Sunni majorities in Syria and elsewhere. This does tend to have a disproportionate impact on the way minority groups are able to attract solidarity.

That said, there are lots of very inspiring things happening within the Kurdish movement in northern Syria which are directly attractive to anti-authoritarians and anarchists in the West, and I see why there’s an appeal. But there have also been plenty of very inspiring things happening in other parts of Syria. One of the untold stories of the Syrian revolution is how in the absence of the state, when the state collapsed or was pushed out of the majority of the country, people came together and began to build alternative structures for self-organization within those areas.

For example, when the state withdrew and pulled out services, people realized that they needed to build forums to keep their communities functioning. The model that they looked to was developed by a Syrian anarchist called Omar Aziz, who advocated for the establishment of local councils, grassroots forums in which people could come together to discuss the needs in their community and self-organize to keep services functioning, such as electricity supply, hospitals, water supply systems, education systems. That model spread throughout Syria, leading to the establishment of hundreds of local councils throughout the country.

These experiences of self-organization and autonomous politics that happened as a direct result of the Syrian revolution should have been something that people outside were looking at and learning from, and that was a missed opportunity. Possibly some of that was on us, on our inability to communicate effectively what was happening. But also we had a lot of other priorities. It should have been people on the outside looking at what was happening inside Syria and seeing how they could find access to better information.

FS: To close, where do you think the people’s more democratic movements in these two venues are going? Are there any things to keep an eye on? Any direct ways, other than countering disinformation, that folks in the listening audience can support people who are struggling for autonomy and to uplift their dignity in Syria and Lebanon?

There has been an outburst of creativity. Arts and music genres that hadn’t been explored before are now being explored, like metal and rap and hip-hop. Lebanon is freer than Syria as a society, there are less restrictions; there is a bit more breathing space to create some of this infrastructure that is now booming. Currents like environmentalism, feminism, queer rights, and so on are finding momentum in the ongoing revolutionary upheavals.

LS: I would love to talk about all the opportunities for political solidarity, to build the free Syria that we all want to see. But Syrians are facing a war of extermination right now. The situation on the ground is so absolutely desperate in places like Idlib that any immediate call has to be a purely humanitarian call, to try to pressure a ceasefire, to stop the assault by Russia and the regime on residential communities, to stop this humanitarian crisis from spiraling absolutely out of control, which it is doing at the moment.

I would encourage people to look at some of the Syrian-led organizations which are providing support to these internally displaced people on the ground. The Molham Volunteering Team is a wonderful organization doing wonderful work. Violet Organization, Kids Paradise—the immediate needs for survival take precedence over any other call I think of right now.

And then I’ll reiterate what we’ve been saying about being more informed—there are still many Syrians working to try to hold this regime accountable, to try to keep going with their desire to live in a free country. I encourage people to find out who they are and to see which ways they can stand in solidarity with them.

JA: As for Lebanon, what’s been happening in the past almost four months is often described as a rebirth. There is a lot of very new momentum. Some of the media outlets that I mentioned before were literally launched in the past few weeks. A few of them are the offspring of the 2015 movement, but others are really much newer than that. There are websites that only have half a dozen articles and they are just building on that.

That’s the exciting part. We’re having an emergence. There is an emergence of a civic-society mentality—though that has a lot of limitations. Sometimes it’s limited by a liberal paradigm. But it creates a space. It’s a moment to push for ideas that are more progressive. That’s what folks like me are trying to do. I am just a writer. Other people are doing much more direct work on the ground. There are soup kitchens that have popped up in places like Beirut and Tripoli. There are independent unions being formed because the current unions are either co-opted or useless. There are independent media workers—while there are good people working within mainstream outlets, they tend to be limited by those outlets’ priorities.

At the same time, in the same way as in Syria, there has been an outburst of creativity. Arts and music genres that hadn’t been explored before are now being explored, like metal and rap and hip-hop. Lebanon is freer than Syria as a society, there are fewer restrictions. There is a lot of self-censorship, but not as much of the overt censorship that there is in Syria. You can pretty much say whatever you want, within some limits sometimes, and that has allowed us a little bit more breathing space compared with what Syrians have had, to create some of this infrastructure that is now booming. Currents like environmentalism, feminism, queer rights, and so on are also finding momentum in the ongoing revolutionary upheavals.

The only limitation so far is refugee rights, and migrant domestic worker rights. The revolution hasn’t really addressed these issues as much as it should. But hopefully the more we continue and the more progressives and others manage to steer the revolution in a certain direction rather than in a nationalist direction, that might be possible in the near future. I personally think it’s going to be extremely difficult, but there is hope in that matter.

LS: One other area that I’d like to draw attention to is the prisoners’ struggle. The prisoner issue is something that everybody should be supporting. There are thousands of Syrians in prison, and we know the horror stories of how widely practiced torture is within regime detention. Those are our people. Those are the peaceful pro-democracy activists who were struggling against this regime. They are the people who are inside prison who we should be supporting.

There are some fantastic organizations that people can get behind. Families for Freedom is a women-led movement set up by Syrian women: the mothers, wives, sisters of political prisoners. It is a movement that was inspired by Argentina’s Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, and by a similar women-led movement looking for the disappeared in Lebanon. They’re doing as much work as they can trying to keep the issue of prisoners on the international agenda, calling for the release of not only those detained in regime prisons but also those detained in prisons by Islamist groups.

That’s something that everybody should be getting behind and finding out about and seeing how they can support, because it’s never on the agenda even though for every Syrian, it’s one of the most important issues because we all have family members or friends who have disappeared in regime detention.

We spoke a lot about how exhausted and traumatized Syrian activists are right now because of the strength of the counterrevolution and what they’ve gone through over the past few years. But one thing that has given us so much hope and strength and inspiration is seeing the protests happening in Lebanon. Also in Iraq, where people have been out on the streets and going through extremely challenging circumstances—this is also very inspirational in the way they are using anti-sectarian slogans. Also what’s happening in Iran with the protest movement there. All these movement have given us a lot of hope and courage.

Syria has been used to silence people across the region as a kind of bogeyman: if you raise your voice and demand freedom, this is what’s going to happen to you. You’re going to end up like Syria. The revolutions and uprisings that happened in 2010-11 have been crushed, they’re over. But they haven’t been crushed. This is part of a long term process. Although each country has its own specific situation, there are a lot of similarities: the authoritarian regimes, the corruption, the bad socioeconomic situation. And people are not being silenced. Something changed in 2011, and despite the massive repression these protest movements have faced, something has changed within people. That’s going to have a massive impact on the future. There’s going to be a lot of change happening in the region, and we’re only at the start of that process.

FS: Thank you so much for having this conversation, I really appreciate it.

LS: Thank you for inviting us.

JA: Thanks a lot.

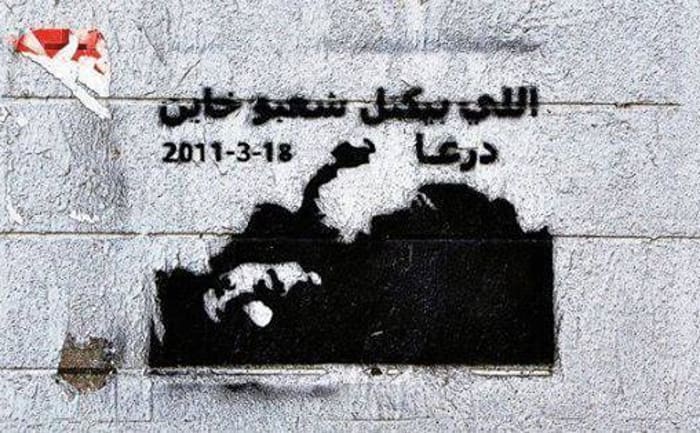

Featured image: Protest sign in Beirut, October 2019, reading “Syria and Lebanon: a Revolution Against Tyranny.” Source: an excellent Twitter thread on how the Syrian revolution featured in the latest Lebanese protests.