Transcribed from the 26 November 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Any reasonably thoughtful adult would readily concede that a shared meal is a very poor representation of colonial-Indigenous relations. The more common features of colonial American history were Indian-colonial wars and race-based slavery.

Chuck Mertz: Thanksgiving is supposed to be about giving thanks for something—I’m not really sure what, but something. I’ve never really been clear what this holiday is actually about, and apparently history has been pretty unclear about it too. Here to help us learn the true meaning of Thanksgiving, David J. Silverman is author of This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. David is professor of history at George Washington University and specializes in Native American, colonial American, and American racial history. He is an award-winning author, and his most recent book prior to this one is 2016’s Thundersticks: Firearms and the Violent Transformation of Native America.

Welcome to This is Hell!, David.

David J. Silverman: Thanks for having me.

CM: You write, “Serious critical history tends to be hard on the living. It challenges us to see distortions embedded in the heroic national origin myths we have been taught since childhood.”

How traumatizing can critical history be? What happens when that trauma is confronted by denialism?

DS: In the case of the Thanksgiving myth, it forces Americans to come to the realization that colonization was a bloody affair—that it wasn’t consensual, and that Native people didn’t just disappear after the Thanksgiving dessert was served. We have to take a more critical look back on where our country came from and recognize that there are colonial legacies that live with us to this very day, not least of all the fact that we all live on lands seized from indigenous people, and that the racial hierarchies that are so embedded in our society are a colonial legacy.

It forces us to take a more critical look at our present and our future, and to ask ourselves whether we want to do better than our forebears.

CM: In really general terms, it seems like what we are trying to avoid is how the United States was born out of violence. Why don’t we want to have an origin myth of the United States that includes violence?

DS: There are all kinds of reasons for that kind of historical amnesia. Those who don’t want to confront this history worry about what justice will look like moving forward if we acknowledge the truth. My job is not to craft policies that will promote justice in our society. My job is to get the history right, and so that’s what I do.

Many white Americans in particular believe that the purpose of a history education is to create patriots: to cultivate people who are proud of their country’s history, as opposed to people who can analyze their country’s history critically.

CM: Is there are a fear, from people who are in denial about our violent past, of retribution for that violent past?

DS: For certain. Their main concern is that there will be a redistribution of wealth in order to address some of these historical wrongs. They are also often concerned that folks who have previously been voiceless or powerless in our society will have a stake, and want their interests represented in our policies.

CM: How does the way we celebrate Thanksgiving—how might that undermine any potential for, let’s say, reparations for Native Americans?

DS: The Thanksgiving myth as it’s been propagated in American society since the late 1800s is a sanitized version of colonial American history. The first thing it does is sanitize New England’s history. It refuses to address the fact that the relationship between the Wampanoags and the English very quickly degenerated into violence, and eventually into the terrible King Philip’s War of 1675-78. It refuses to acknowledge that even in New England, colonists held slaves–and not just Africans as slaves, but indigenous people, including the Wampanoags.

The Thanksgiving myth takes a sanitized version of New England’s history and makes it a symbol for colonial America at large. Any reasonably thoughtful adult would readily concede that a shared meal is a very poor representation of colonial-Indigenous relations. The more common features of colonial American history were Indian-colonial wars and race-based slavery. As a historian I would prefer for us to focus on those very real themes than the mythical Thanksgiving feast.

CM: I’ve often heard people in the north—people including me—complain about the denialism that we often hear from people in he south, from people who might fly confederate flags: the denialism of the long legacy, that continues, of African-American slavery in the south.

Yet here in the north, we seem to be in even greater denialism of Native American slavery, because it’s something that never comes up at all. It was only a couple years ago that the author of a book about Native American slavery was on our show to discuss the concept.

Have we erased Native American slavery and the institutions and legacy of slavery in the north far more than even the south has?

DS: It’s been common in American history circles to refuse to address that very basic feature of colonial American history. As your listeners might know, given that you’ve had historians on previously who specialize in this area, our best estimates nowadays are that somewhere between three and five million indigenous people suffered slavery at colonial hands in this hemisphere during the greater colonial era. That higher number is forty percent of the estimated volume of the transatlantic slave trade. So this wasn’t some kind of eccentric exception to historic patterns of slavery in the colonies.

There’s no question about it. The north has engaged in its own historical amnesia just as the south has, and I think the Thanksgiving myth and its whitewashing of Indian-colonial warfare, of colonists’ aggressive and underhanded engrossment of Native American land, and of the enslavement and forced indentured servitude of indigenous people is part of that sanitation.

The whole point of the exercise is to have Native people voluntarily cede their territory so that the United States can become a beacon of liberty and Christianity and democracy, and then after the dessert is served, the Indians just disappear.

CM: You write, “A history of English-Wampanoag relations turn the bedtime story of the Thanksgiving myth into a nightmare. European mariners called ‘explorers’ by historians were in fact slavers who raided the Wampanoag coast for years before the pilgrims’ arrival, capturing people for sale to different places of which they had never heard. The Plymouth colonists were no better; despite their claims to piety, they introduced themselves to the Wampanoag by desecrating graves and robbing seedcorn from underground storage barns. Nevertheless, Massesoit, the tribal leader, extended a peaceful hand to the newcomers—not out of innate friendliness but pity, and because his people needed allies against their Narragansett Indian rivals after the Wampanoag suffered a devastating epidemic introduced by Europeans. This horror was the dark background to the supposed first Thanksgiving.”

What happens to our understanding of our national origin when we erase slavery, thievery, and all of the attacks and violence from the pilgrims? When I was a little kid looking at a pilgrim with all those buckles—I never really understood all those buckles—I didn’t know what the “pilgrims” really did. What happens when we erase slavery from the history of the pilgrims?

DS: The Native actors, and for that matter the English actors, become caricatures of themselves. In the Thanksgiving myth, friendly Indians—there’s no explanation for why they’re friendly, and there’s usually no tribal identification of who they are—reach out to the pilgrims not because they wanted a defensive alliance, not because they wanted trade, but because supposedly they wanted to gift their country to foreigners. The whole point of the exercise is to have Native people voluntarily cede their territory so that the United States can become a beacon of liberty and Christianity and democracy, and then after the dessert is served, the Indians just disappear. There’s no explanation of where they went, if anywhere, or of how the history of relationship between these two peoples went after the meal.

Again, the people just become shadows of themselves. Telling the history in that mythical way doesn’t require us to think hard about how torturous it really was, about how bloody it was, about how violent colonialism is by its very nature, and that that foundation is the bedrock of our country.

CM: You write, “The dishes had barely been cleared from the first Thanksgiving before a litany of English crimes began to mount: atrocities like the New England colonists’ 1637 massacre of the Pequots of Mystic Fort (which Connecticut and Massachusetts memorialize on the day of Thanksgiving), cheating Indians out of their land, herding them into reservations and making them trespassers in their own country, exploiting Indian poverty and English control of the courts to force Indians into servitude, degrading Indians by calling them savages at every opportunity. The moral of the first Thanksgiving was that the English and their descendants betrayed the Wampanoags who had once befriended them in their time of need.”

Is the real story of Thanksgiving that of betrayal? And is the lesson for Native Americans a reminder that white people cannot be trusted, that the United States cannot be trusted?

DS: Let me be clear to your listeners. Native people have been confronting white Americans with the hypocrisy of their sanitized history since the 1600s. They’ve been quite vocal about all that. But there’s no reason why this false history has to be attached to Thanksgiving. It hadn’t been before, during the 1600s or the 1700s or the first several decades of the 1800s. Indeed, Americans had been celebrating Thanksgiving without any reference to pilgrims and Indians for quite a long time—actually, for longer than Americans have now been making that association. That association is an invention of the late 1800s.

We were talking earlier about the way the north has sanitized its own history. This invention came at a time when Anglo protestants in the northeast felt like their cultural authority was slipping away. There was an influx of non-protestant immigrants from parts of Europe that hadn’t been represented in the United States in force up to that time. Also, the country was expanding to the west. And finally they wanted to distance themselves from what contemporaries considered to be the Black and Indian Problems—the Black Problem being Reconstruction in the south, and the Indian problem being the US-Indian wars of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountain west.

This false Thanksgiving myth was an invention of mostly Anglo protestant New Englanders who wanted to hold up their ancestors as the Founding Fathers of the Country. Well, look, here we are a century and a half later. We don’t need to do their bidding any longer. We can get together with family and friends and be thankful for the goodness in our lives without propagating a false history, and a damaging one at that.

CM: A false history, granted, but how well did the invention of Thanksgiving in 1863, when the country was divided—how well did that work in bringing the country back together? How well does it work as a tool of national unity?

DS: It has worked for white people for the better part of a century and a half. At the time, southerners in particular were quite resistant to taking up the celebration of what they considered to be a Yankee holiday. Thanksgiving was a Yankee holiday. But eventually it took hold.

One of the reasons it took hold in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was a widespread white protestant anxiety over non-protestant European immigrants to the country—Catholic, Jewish, Eastern Orthodox, and the like. It also took hold when it did because it’s a myth that asks Americans from a variety of backgrounds to identify with the pilgrims as “we,” and to think of the Native people as “they.” Even in a classroom full of Europeans from various ethnic backgrounds, the children would be asked to see the pilgrims as “my forefathers.”

That’s part of the way that people with last names like mine, Silverman, were indoctrinated into conceiving of themselves as white people. That’s another reason why this myth has taken hold the way that it has.

CM: You write, “The national origin myth upholds the traditional social order by teaching that the rulers came by their position heroically, righteously, and even with the blessing of the divine. Such themes are favored by those guarding their privilege against the supposed barbarians at the gate.”

The blessing of the divine—is there something akin to an adoration of monarchy within the national origin myth and, say, through the framers of the constitution, the “founding fathers?” Did we inherit certain aspects of monarchy within our national origin myth despite our national origin being about overthrowing a monarchy?

In the late 1860s and 1870s, Massachusetts divvied up the half-dozen or so Wampanoag reservations throughout the state, granted citizenship to indigenous people, and then declared them no longer recognized as Indians.

DS: All political and social orders want to buttress their authority by trying to indoctrinate people with the idea that god—or whoever their spiritual authority is—wants that particular social order to exist. In European history, there was the divine right of kings: the king and/or queen is the representative of god on Earth. That’s been democratized in the American through Manifest Destiny, the idea that god blessed the United States to expand, not at the expense of Indigenous people, not for the purposes of spreading slavery, but to spread liberty, democracy, and Christianity, and thereby salvation, through its expansion.

The Thanksgiving myth is very much an iteration of the ideology of Manifest Destiny. Here we have Native people voluntarily ceding their country to these pilgrims, without any bloodshed! In the myth, god wants that to happen. Think of the songs that accompany the grade school Thanksgiving pageants which have been so common in American schools for the better part of the century, songs like “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” This country is blessed by god!

CM: You mention attempts on a peninsula at Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, beginning in the 1860s and 1870s, to “finally make Indians as a group vanish, as nature supposedly intended, by bringing their land into the market and forcing them to scatter and assimilate among the larger American population.”

Vanishing as nature intended, by bringing their land into the market—which makes the market a natural function. How often do we accept crimes against humanity as simply nothing more than the outcome of market forces? Does the market make even genocide invisible? Is Thanksgiving about erasing the violence of the market?

DS: One of the most sinister aspects of white American dispossession of Indigenous people has involved taking Native people’s communal land holdings, dividing them into private property tracts, and then subjecting those private property tracts to taxation and confiscation for debt. Private property has been a basic pillar of white American society since the beginning of the United States, but for Indigenous people the private property regime is an assault on their peoplehood.

When communal lands are divided and subject to taxation and confiscation for debt, it’s a guarantee that a sizable portion of the people will have to scatter as they fall into financial straits. Communal landholding usually doesn’t provide the mechanisms for many people in the community to get far ahead of the group, but it also means that not that many people fall all that far behind. It allows the group, as a group, to stay together.

In the late 1860s and 1870s, Massachusetts divvied up the half-dozen or so Wampanoag reservations throughout the state, granted citizenship to indigenous people, and then declared them no longer recognized as Indians. At that time, being Indian and being a citizen were considered antithetical to one another. The white authorities who pushed these policies had absorbed the ideology of Manifest Destiny and trafficked in this notion that Native people were savage, pagan peoples—inferior peoples, destined by god to disappear. So the fact that giving up their communal lands would speed this process along was seen as a way of promoting destiny, not as an assault on indigenous people.

CM: Did we need victory over Native Americans, even through genocide, before we could incorporate Native Americans into our national origin myths? Was the incorporation of Native Americans into our national origin myths the final site of subjugation of Native Americans by colonists?

Did we need to wipe them out before we let them into our myths?

DS: I think so. I’m often asked by audiences who have read this book or heard me talk: couldn’t it have gone better than it did? And my answer is no, it could not. Indigenous people, whether in North America or anywhere else around the world, didn’t concede to their own subjugation, didn’t concede to foreigners seizing their lands and asserting their jurisdiction. Everywhere around the world, including in New England and in North America more generally, Indigenous people resisted.

If Europeans were going to establish colonies, and later establish a nation-state which claimed the continent, it was going to be bloody work, in terms of relations with indigenous people. And as long as indigenous people were resisting, one could not expect those against whom they were resisting to incorporate them into a national origin myth. The subjugation had to be finished before that process could occur.

CM: What’s wrong with imbuing Native Americans with a sense of kindness and care within a US origin myth about Thanksgiving? As the story goes, they open their hearts and their homes and their fields to the pilgrims, to the colonists. What’s wrong with imbuing Native Americans with that sense of kindness and care?

DS: First of all, it’s not true. Depicting the Wampanoags as innately friendly when they reached out to the English robs them of the context in which they were operating. Ousamequin, their sachem, who was in charge of this diplomacy, faced a great deal of opposition among his own people. They had suffered a century of European raids on the coast, in which Europeans very often enslaved Wampanoag people and sold them overseas, or brought them back to England for training as interpreters and guides. Understandably, Wampanoag people were quite wary of Europeans and opposed to them establishing permanent settlements along their coasts.

Ousamequin made this decision not because he had some kind of love for the Europeans but because his people had suffered a terrible epidemic disease between 1616 and 1619, just before the arrival of the Mayflower. His people were hobbled, and their Narragansett tribal rivals to the west were trying to subjugate them to tributary status. The Thanksgiving myth does violence to this actual history.

More importantly, the Thanksgiving myth makes light of Indigenous people’s very real historical traumas. It depicts the only authentic Indians as frozen in time at the moment of contact, and it blinds Americans to the existence of Native people in modern times. It blinds modern Americans to the ways Native people have resisted colonization across the centuries, the ways they made it through the apocalypse—they were really staring genocide in the face—and the ways they have adapted to become part of contemporary society.

Native people are not some kind of subjugated foreigners. They are our countrymen and -women. They are part of our national fabric. We shouldn’t be propagating a historical lie tied to a national holiday that does damage to any part of our national community.

CM: You write, “The name ‘Day of Mourning’ hearkened back not only to the recent national days of mourning held throughout the United States after the assassinations of John F. Kennedy in 1963 and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. It also evoked the eulogy of King Philip written in 1836 by William Apess, a Pequot preacher and activist who served the Wampanoag community of Mashpee. In his eulogy, Apess declared the December 22, 1620 anniversary of the pilgrims’ landing and the Fourth of July to be days of mourning and not joy for Indians, because of the evils whites had done to them.”

That’s 1836. So how new is the understanding that the United States did a horrible wrong to Native Americans? Did the colonists actively erase Native Americans from their history, or were they simply unaware of Native American history, because why pay attention to a civilization that you’re going to destroy?

The Thanksgiving myth teaches white proprietorship in the nation. It doesn’t just neglect the Native American role, but it teaches that white people were destined to rule this country, and that from the start they were in control.

DS: Generations of white historians—a disproportionate number of whom were trained at northeastern universities like Harvard and Yale—believed that the point of history was to tell a narrative of progress. The reason that Native people weren’t important in that narrative is that Native people were supposedly ‘primitives.’ They weren’t part of human society’s march towards progress, towards betterment. What was the point in telling their side of the story?

A great many Americans have been passive recipients of this kind of history, and weren’t taught to think about it critically. But Native people have been criticizing this kind of whitewashing since the very inception of the United States—indeed, all the way back to the revolutionary era and before that, during the colonial period. William Apess, Pequot minister to the Mashpee Wampanoags at Cape Cod, was one of the most eloquent proponents of this view, and he’s the first one to introduce the idea that on the on July 4 and December 22 (the anniversary of the pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth), Native people should pause and mourn what they have lost.

I should note, by the way: Apess made this speech in front of an all-white audience in Boston, in the middle of the period of Andrew Jackson’s removal of the eastern tribes. One of the reasons he chose that particular setting is that white New Englanders were among Andrew Jackson’s fiercest critics. What Apess was saying was, “Don’t get on your high horse. Look in your own backyard at the way you treat your own Indigenous neighbors.”

CM: Is celebrating Thanksgiving sadistic? You write, “Thanksgiving eclipses Columbus Day as the one time a year when the country considers the Native American role in the nation’s past. It is bad enough to have gotten the story so wrong for so long; it is inexcusable to continue the annual tradition of having a phalanx of teachers, politicians, and television producers traffic in the Thanksgiving myth, and homeowners and shopping centers sport decorations of happy Indians and pilgrims. These practices dismiss Native people’s real historical traumas in favor of depicting their ancestors as consenting to colonialism. To call the consequences harmless is to ignore the chorus of Native Americans, our fellow Americans after all, who say the hurt is profound, particularly to their children.”

So is celebrating Thanksgiving sadistic? Is it deriving pleasure from inflicting psychic pain, suffering, or humiliation on others?

DS: I think it’s neglect more than anything else. Most Americans don’t recognize that Native people are part of modern society, and therefore don’t take their feelings into account.

I think it’s cruel by neglect. I don’t think most people are intentionally trying to hurt their Native American countrymen and -women. But the way we celebrate the holiday is damaging in another way as well, that might not be so readily apparent. The Thanksgiving myth teaches white proprietorship in the nation. It doesn’t just neglect the Native American role, but it teaches that white people were destined to rule this country, and that from the start they were in control.

The only way that we’re going to come to terms with how we’ve come to this white nationalist moment, with a white nationalist president promoting policies that are attacking people of color in every iteration around this country, is to recognize that this mentality is upheld by a thousand different buttresses. I would contend that the Thanksgiving myth is one of those buttresses.

CM: You write, “The question was and still is how to move forward.” But how possible is it to move forward when there are so many who are in complete denial of Native genocide and white betrayal? How possible is it to move forward when there seems to be a resurgence in this belief in white supremacy and privilege? Do you see any signs that we are more open to reconsidering our national origin myth as what is is, a myth?

DS: I think half the country is and half the country isn’t, and we have a major fight on our hands. I think the white nationalist moment is in no small degree a backlash against the fact that white people aren’t going to represent a majority in this country for long, and will have to cede a significant amount of their power to that basic demographic truth. I have found that there is a sizable portion of the American public that is open to the message that I am promoting. I’ve seen it in people who have attended talks that I have given; I have seen it in the fact that radio shows like yours and many others are interested in this story.

I’m not naive. I’m not suggesting that achieving these goals will be easy. It won’t. It’s going to require a fight. We just need to keep pushing our views, and I am hopeful that if we do that and if we don’t tire out and if we don’t bow to convenience, that the truth will win out at the end of the day.

CM: We should celebrate this or memorialize this as a Day or Mourning, not as a day of thanks. We should remember that this is a day that reinforces myths that prop up white supremacy and white privilege and continues the legacy of racism and colonialism that Native Americans experience each and every day. So David, what do we serve at the Thanksgiving meal when it’s a day of mourning?

DS: Many Wampanoags I know celebrate Thanksgiving. I’m not trying to discourage anybody from getting together with family and friends to reflect on the goodness of their lives. But if we’re going to attach the story of pilgrims and Indians to the holiday—and I don’t think we need to—we need to get the story straight. That turns the story from one of celebration to one of reflection. I think many people will reflect in the spirit of mourning, which I believe is entirely appropriate to the real details of the story.

CM: David, I really appreciate you being on our show, thank you.

DS: Thank you for having me and thanks for fighting the good fight.

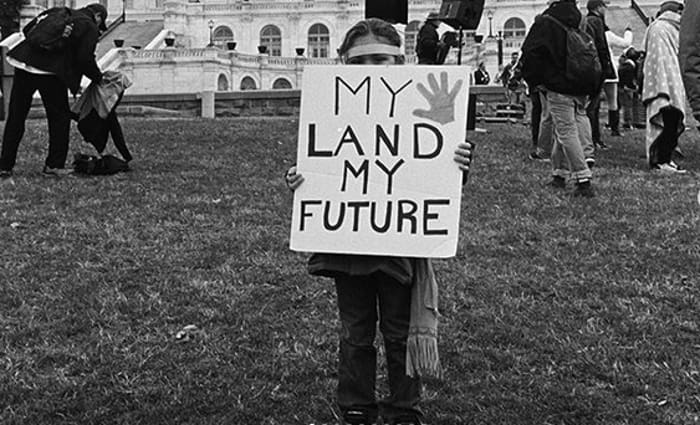

Featured image: Mashpee Wampanoag Land Sovereignty Walk and Rally, Washington DC, 2018. Source: Portugal The Man (Twitter)