Transcribed from the 12 March 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

There’s unfinished business. There are treaty obligations, and we have to address colonization, so we’re not going to just politically assimilate into your interior state.

Chuck Mertz: For centuries, Britain and then Canada stole land from the Indigenous in the area we now know as Canada—and they did it “legally,” within the fiction of their law that was based on complete nonsense. The outcome of that theft was the devastation of a culture, a people, and language that would become twisted by the society which tried to assimilate them, with tragic results.

Here to explain why giving land back to Canada’s Indigenous is not only fair and right and just, but it might actually be a huge step towards saving us all, our guests Dr. Hayden King and Dr. Shiri Pasternak are contributors to the new Yellowhead Institute red paper entitled “Land Back.” Dr. King is executive director at Yellowhead Institute, and Dr. Pasternak is research director.

First, welcome to This is Hell!, Dr. King.

Hayden King: Aniin, welcome, thanks for having me.

CM: And welcome to This is Hell!, Dr. Pasternak.

Shiri Pasternak: Hi, thanks for having us.

CM: Let’s start with you, Dr. King. You write, “From 1968 to 1969, the federal liberal government led by Pierre Trudeau drafted a new Indian policy as a response to the activism of Indigenous leaders. The document proposed a shift away from oppressive and discriminatory government policies rooted in inequality, or as Trudeau put it, ‘A just society for Indigenous people.’ It was a demand for integrity from Canadians, honoring treaty rights, restitution, self-determination. The white paper, as the new policy became known, betrayed those demands and prescribed political and legal assimilation into Canadian society. This, of course, was more of the same.”

Hayden, what was the point of coming up with a new policy if in fact it ended up being more of the same? And did it placate the Indigenous activists at the time who had pressured Pierre Trudeau to do something?

HK: This is one iteration of a very long historical phenomenon—one moment in this very long history between Indigenous people and Canadians, and I would go so far as to say Indigenous people and Americans. Settler-colonialism on the continent has gone through these phases where colonization unfolds, Indigenous people resist, and then often federal officials will try to contain that resistance in some way. In this case it was to say, “Okay, well, we’ve stolen all your land and oppressed all your people and kidnapped your children. We realize that was probably wrong, so we’re going to create a new policy to fix all of that.” In 1951, the same thing was attempted, and you can trace this back further. Every generation or so there is one of these moments where an attempt at reconciliation unfolds.

The white paper was just one of those attempts, and it was responded to by Native leaders with anger, because ultimately—like all of those previous attempts—it was really just an attempt to rescue colonization, to rescue Canada, and really change nothing fundamental about the relationship. We saw that before 1968-9, and we see it after 1968-9.

CM: Was one of the shortcomings of the white paper that it was more about incremental reforms and not any kind of systemic challenge?

HK: It wasn’t even about incremental reforms. What the government of the day was attempting to do was disguise an attack on treaty rights and Indigenous rights as progressive change. They thought the best way forward was to privatize all Indigenous land, to have Indigenous people fall under provincial jurisdiction, and just to get on with the relationship as legal equals—during a civil rights movement. But Indigenous people of course were saying there’s unfinished business. There are treaty obligations, and we have to address colonization, so we’re not going to just politically assimilate into your interior state.

CM: Dr. Pasternak, the red paper states, “In response, First Nation leaders in Alberta drafted Citizens Plus in 1970, known as the red paper. The red paper was a constructive alternative to Canada’s vision. Yellowhead Institute is inspired by the notion of the red paper as a productive vision of Indigenous futures that critically engages with Canadian frameworks. In the case of our red paper, we aim to link Canadian policy prescriptions more closely to land and resource management and to outline the corresponding Indigenous alternatives. Like the 1970 original, we aim to support communities with additional information, ideas, and tools to respond to federal plans on their own terms.”

Shiri, why the focus on land and resource management? Is the fight for Indigenous rights the fight for land rights? And if so, why?

SP: That’s a really deep question about the nature of anti-colonial struggle in Canada. This is the second major report that Yellowhead put out; in our first one we focused on policy and legislation that the government is introducing in order to make gestures towards incremental change, towards recognizing land rights. In this report, we go right into the heart of the issue of the ongoing forms of dispossession that we need to be attentive to in order to understand what all of those gestures of recognition look like and how they fall short of actual restitution and redistribution of land.

You can’t really get away from the fact that the entire state formation project and the political economy of Canada today are premised on the dispossession of Indigenous land. If people are going to have an economic base of self-determination, we’re going to have to address the restitution of land and the original form of oppression, which is dispossession, in Canada.

CM: The red paper also cites Harold Cardinal, who you describe as “critical to the creation of the first red paper, recognizing nearly fifty years ago writing in The Unjust Society that ‘the old religion of the Indians’ forefathers slowly twisted into moral positions that had little relevance to my environment—twisted to fit seemingly senseless concepts of good and bad.’ Whether through residential schools, Indian agencies, or Christianization, this ‘twisting’ manifested itself in dismantling the power of women, evacuating the ceremony meant to honor the animals we hunted, and the rise of homophobia and lateral violence. And so, going back to Harold Cardinal’s writing: ‘A return to the old values, ethics, and morals old Native beliefs would strengthen our social institutions.’”

Shiri, this twisting was the process of European assimilation. Why does Indigenous culture, when twisted with white European culture, lead to the disempowerment of women, the rise of patriarchy, homophobia, lateral violence—that is, more violence among one another? Why does that happen to Indigenous culture when white European culture is imposed upon it?

SP: The answer is really to turn the gaze onto white European culture and to look at the organization of societies through patriarchy that relied on the subjugation of women and the devaluing of women’s knowledge. With colonization, primarily through education systems but also through cultural exchange and contact, these ideologies of patriarchy were imposed upon Indigenous people that are then internalized through colonial structures of governance like the band council system that’s introduced through the Indian Act.

Indigenous people have understood for a very long time that if you don’t take care of that which sustains you—the land, the water—then you’ll die. In very straightforward ways. That’s what we’re all experiencing right now with climate change.

CM: Hayden, the red paper also mentions how “assimilation by force, from residential schools, Indian agents, or Christianization also led to evacuating ceremony that was meant to honor the animals we hunted.” I just want to repeat that because in January, we spoke with sociologist Kari Marie Norgaard, author of Salmon and Acorns Feed Our People: Colonialism, Nature, and Social Action. Kari studies the relationship between the Karuk people and the land of the Klamath basin in northern California and southern Oregon, and she mentions the importance of ceremony when it comes to land management, how those ceremonies were targeted by settler-colonialism, and their potential today for environmentalism is very great, according to Kari.

Was assimilation a religious war on a land management process that was spiritually bound to nature? Was this a religious war?

HK: It’s a conflict over law, really. I come from the Anishinaabeg tradition, and ceremony is important, and understanding how we relate to the land and how we fit into all of creation is important, and that can be thought of as religious in nature. But it can also be thought of in more material terms, in really pragmatic ways. Anishinaabeg people and other Indigenous people generally have understood for a very long time that if you don’t take care of that which sustains you—the land, the water—then you’ll die. In very straightforward ways. That’s what we’re all experiencing right now with climate change, and Indigenous people, whether they are Anishinaabeg or Klamath or Dakota—across the continent—have since time immemorial developed laws and values and spiritualities that have embedded these really basic principles into how we relate to one another and how we relate to the land.

Of course when settlers arrived and sought to exploit the land and viewed it as a commodity, those original Indigenous values had to be liquidated, they had to be suppressed. Because they posed a threat to extraction and exploitation of the land. This conflict that we’re talking about certainly could be framed as religious, but ultimately it was economic and legal at its heart.

CM: Dr. Pasternak, you write, “The infrastructure to legally steal our lands is important to understand, and so are the concrete promising practices to reassert jurisdiction. But without including a discussion on how those promising practices are being done in a good way, we’ll keep getting it twisted.”

This is the part that really confuses me a lot, Shiri. Is the history of Indigenous lands being stolen by settlers not a history of a crime but something that was, according to the laws written by the settlers, completely legal? If I understand your writing correctly, the logic behind it is that the Europeans ‘discovered’ the land and therefore it is theirs, despite the fact other people had been living on it for thousands of years. That logic just seems absurd.

So was this a legal crime? Was the legality based on an absurd logic?

SP: It goes back to Hayden’s point about the fact that this is a context of legal warfare between different legal systems. Colonization in Canada was strictly by the rule of law—settler law, that is. And it has continued that way until today. Dating back to the imperial legalities of the doctrines of discovery, we still see the arguments of discovery being held up in the supreme court of Canada by the state as the rationale for claiming underlying title to all lands in Canada.

Partly the reason for that is just the racist anthropology that the country is based on. But the other part is more practical, which is that without the doctrines of discovery the state doesn’t have a legal basis for claiming sovereignty on these lands. That’s the foundation of sovereignty in Canada. After the doctrines of discovery that initiated contact and claims of territory, there was a whole slew of colonial legalities that followed that set up the foundations for the Canadian state.

But power doesn’t flow in one direction. What we see when we look at the history of the country and how the law has been used to legislate all kinds of oppressive policies against Indigenous people—from land dispossession to the abduction of children and so on—we also see this constant pushback by Indigenous people that’s shaping the law itself, both in the sense that the Indian Act provisions become more and more oppressive as Indigenous people resist attempts to take over their governance systems and to change the status of women in their communities, but also in the sense that the law has had to break and give in different circumstances.

In 1982, due to the tremendous efforts of Indigenous people, Indigenous rights were patriated into our constitution which were supposed to usher in a new era of lawmaking in the country where Indigenous governments would be considered a third order of government and would have their rights and treaties respected according to Indigenous law. Unfortunately, that has been a very rocky path. But there have been these tensions throughout the formation of law in Canada: it’s been used to oppress Indigenous people but then also taken up as a tool by Indigenous people to push back against its restrictions and limitations on their sovereignty and self-determination.

CM: Shiri, do you know if that doctrine of discovery—is that typical? Is that not unique to Canadian law? Is the same thing being done against the Indigenous anywhere? In Brazil, in Australia, in the United States, is that part and parcel to the whole idea of land theft from Indigenous people?

SP: Certainly what legalized the global scramble for resources and land in the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth centuries was a notion of discovery and the authority of the Pope (then as things changed, royal kingdoms throughout Europe) to claim Indigenous lands. But all of those claims are different according to different national traditions. I am most well aware of the Anglophone settler colonies—the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. And certainly the doctrine of discovery was the foundational legal principle that justified colonization in those places.

CM: You’d think that logic would be overturned by now, and by now that would no longer have any kind of legal power.

Hayden, you write, “This report has been drafted with attention to those speaking back against the Western masculine and exclusionary politics and values that many in our communities have adopted and practiced.” Is this a project to de-Westernize Indigenous culture?

HK: In some ways, it is. I’m not sure I would make the dichotomy around Western versus non-Western, but maybe around Indigenous and settler. Ultimately what we have seen in Canada and the United States since the 1960s and 70s has been a tremendous resurgence in Indigenous culture, politics, economics, philosophy. After being suppressed for so long, there has been a real return to those original values, and the tensions that we’re seeing are between those who are saying “Let’s continue down this path and resurrect our languages and our worldviews and our political economies and legal systems,” and those who are saying, “There’s this mine opening up that we could get jobs in and benefit from.” The tribal chiefs we have in our communities—we call them Indian Act chiefs—derive their power from federal legislation and maybe perpetuate some of those more masculine ideals of what Indigenous community and society is right now.

These are tensions. It’s not a complete project, the resurgence of Indigenous communities and cultures. When I’m writing about those tensions, it’s a conflict that we’re having internally. Really it’s a conversation for Indigenous communities ourselves. What is authentic, as we move through colonization? And how do we ensure that the future we’re creating for our children and grandchildren is an authentic one that’s true to our ancestors?

That’s one challenge that we’re grappling with, amid trying to deal with things like the legacy of the doctrine of discovery and the imposition of settler-colonial laws and the ongoing attempts at cultural assimilation of Indigenous people. To answer your question in a straightforward way, it’s trying to revitalize what being Indigenous is.

The power of that movement was that it was led by women and queer communities and individuals, but also that people took that leadership, which is the critical next step in an actual revolutionary politics: people recognizing who has the authority to make decisions and lead people towards what Indigenous jurisdiction and self-determination will look like.

CM: Shiri, the red paper states that “We have identified cases of land and water reclamation that center women and to a lesser extent queer and/or two-spirit individuals. We have more work to do to amplify these perspectives and experiences. After all, as our board member Emily Riddle has taught us, Indigenous governance is actually pretty gay.”

Shiri, what do you mean by that, and how is Indigenous governance “pretty gay?”

SP: A lot of the leadership resurgence that Hayden just described is being led by queer communities and individuals across the country. Some of the writers who have attempted to theorize this, like Alex Wilson, have talked about the fact that gender, bodies, and sovereignty are deeply intertwined in Indigenous communities. It’s not an accident that queer people are at the forefront of resurgence; it’s actually about the integral ways in which they are connected to, responsible for, and in attunement with the relationship between the health of their bodies and the health of the land.

There’s been a lot of really amazing advocacy. The Native Youth Sexual Health Network is at the forefront of some of this incredible writing. But there are uncountable organizations and individuals who are really leading movements. For example, you saw a lot of these queer and Indigenous women and girls at the forefront of the recent blockades that were erected in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en people who were evicted from their lands by an energy company last month. A lot of those movements were led by these communities and really showed tremendous bravery, strength, and courage in the face of massive oppression that followed.

CM: Are they, then, the people who are making these times revolutionary, as your paper states? “Our times are revolutionary. While tragically little has changed since 1968-70, there are also emerging debates to reflect on and work through together.” So Shiri, is it that leadership, that queer non-heteronormative leadership what is making these times revolutionary for the Indigenous in Canada?

SP: That’s a really hard question to answer. In my personal opinion I see that leadership being instrumental, but instrumental in leading a vast network of coalition-building between Indigenous people and non-Indigenous supporters and allies—which, again, we saw come to the forefront last month with all of these solidarity blockades that essentially shut the country down. The power of that movement was that it was led by women and queer communities and individuals, but also that people took that leadership, which is the critical next step in an actual revolutionary politics: people recognizing who has the authority to make decisions and to lead people towards what Indigenous jurisdiction and self-determination will look like—are we ready to heed that call?

CM: Hayden, the report states, “We continue to grapple with federal and provincial bureaucrats and industry on rights, title, and jurisdiction, but we are increasingly turning inward and we are having productive conversations about what reclaiming land and water might look like for all of us.”

I’m going to hate asking this question, Hayden. It says “All of us.” How much is “Land Back” a challenge to white privilege? Will this be an inconvenience to white supremacy?

HK: Yeah, that’s the reconciliatory question, isn’t it? When I wrote that passage, the “All of us” was meant to speak to all of us as Indigenous people. What does Land Back look like for all of us, as Indigenous people, with the conflicts that we have internally in our communities? But your question does open up space to ask what the role is for non-Indigenous people.

What we try to drive home in the conclusion is that we’re currently facing a climate crisis—all of us are facing a climate crisis—and the practices and philosophy that underwrite Indigenous jurisdiction of land, Indigenous decisions on land and water use are actually the source, the well of knowledge that we can draw on to (at least) help preserve biodiversity. Biodiversity, of course, is the key to ensuring ecosystems are resilient when it comes to adapting to climate change. What we’re ultimately talking about—and I know that this may sound hyperbolic—is Indigenous people helping to save the world. Non-Indigenous people need to understand and recognize that this knowledge is valid and relevant and revolutionary. And the solution, or at least a partial solution, to adapting to climate change is, effectively, Land Back.

It’s important for non-Indigenous people, Canadians or Americans, to get behind that and to lend their support to the types of strategies that we describe in the paper.

CM: Shiri, I want to get back to a point that both you and Hayden were touching on earlier. If Indigenous culture and spirituality and ceremony are centered around nature, and capitalism depends upon resource extraction for fuel and industry, is Indigenous culture, as well as rights, law, and religion, anti-capitalist? And if so, does that explain why Indigenous cultures are so often victims of genocide by capitalism and its supporters? Because they just don’t fit within capitalism?

SP: I don’t want to answer for all Indigenous people about whether they are anti-capitalist. But certainly we can look at the relationship between capitalism and colonialism in Canada and the States, and draw pretty concrete conclusions about the intersectionality between those forms of power. Especially in Canada—to a greater extent than in the US—resource extraction was the main engine for colonization and settlement. There is an entire infrastructure for this country that is based on the dispossession of Indigenous people, and that infrastructure continues to be the basis of the Indigenous economy. Our dollars are to a great extent petro-dollars. So the prioritization of capitalism and particularly fossil fuel-based capitalism is really having a disproportionate impact on Indigenous people—although obviously it affects us all.

There are definite relationships between an anti-capitalist and an anti-colonial politics here, especially in Canada because they are so deeply intertwined. It’s not just the oil and gas industry, it’s also our hydroelectric industry (which is considered a green energy but has caused catastrophic impacts on communities through diversions and dams on their territories); the mining industry (which is one of the biggest in the world); forestry; and other industries. From the perspective of anti-capitalism, just from my personal perspective, investments in alternative forms of economic organization as well as a transition to green energy—as long as it was centered on and led by Indigenous people—could really be a conjoined way out of both capitalism and colonialism. If people were actually committed to making those kinds of changes.

CM: Hayden, the red paper states, “Women, queer, transgender, gender-diverse, and two-spirit people have never been the beneficiaries of these new distributions of power through colonization. Rather they were targeted and disempowered, removing the challenge they posed to the patriarchy of Western systems of governance. The system was in many cases internalized by Indigenous communities and often reproduced through misogyny in First Nation governments. Women and queer Indigenous people are excluded from management, jurisdiction, decisionmaking, and contemporary policy and politics, which results in, among other things, environmental and sexual violence.”

Women, queer, and transgender people, especially when Indigenous, are seen as challenges to patriarchy, so they are discriminated against, subjugated. But is it possible for there to be a capitalism without patriarchy? Can’t we have a capitalist matriarchy or a capitalism that isn’t either, that is gender neutral, giving all gender identities fair and equal rights? Or is that just simply not how capitalism works?

Man camps have been correlated with incredible rates of violence against Indigenous women. This goes back to the 1960s, when there were reports from Manitoba Hydro about impacts on Indigenous women—sexual violence both by workers but also by local police forces.

HK: That’s a big question. Ultimately when we’ve looked to Indigenous feminist thought and we look to Indigenous queer thought, we see a lot of attention to care, a lot of attention to love, and I think that’s really what Emily Riddle was talking about when she said that Indigenous governance is actually kinda gay. These are frameworks of tenderness.

If we conceptualized funding methodologies or GDP or wealth generally along these lines of care, then we would have a radically different economic system, a radically different political economy. Capitalism, at least as it’s been practiced and as far as my knowledge of it, really rests on exploitation: exploitation of land, exploitation of labor. That’s a framework that has evacuated all care, evacuated love, evacuated these principles of supporting one another in an economic system.

Fundamentally, at the most general level, I think there’s an incompatibility there that is perhaps impossible to reconcile.

CM: Shiri, the report states, “Land alienation must also be understood through gender dynamics, which are instrumental to how land loss and dispossession unfold and impact people’s lives. Gender is also critical to the ways in which the right to consent is denied to Indigenous peoples. They might have the right for consultation, but certainly not the right to consent.”

How is land alienation linked to gender dynamics?

SP: Let me give one example that’s been at the forefront of a lot of incredible activism right now, which is the construction of man camps associated with large industrial development. The construction of pipelines, for example, through Indigenous territories is often accompanied by camps of men, up to a thousand people, who are temporary workers: they work long hours, have access to a lot of cash, and often are heavy drug users as a result of needing to put in incredibly arduous shift hours.

Man camps have been correlated with incredible rates of violence against Indigenous women. This goes back to the 1960s, when there were reports from Manitoba Hydro about impacts on Indigenous women—sexual violence both by workers but also by local police forces. This has been a huge issue for a lot of Indigenous women who are protesting or contesting the construction of fossil fuel infrastructure through their territories. One of the examples that we look at in the “Reclamation” section of the report are the Tiny House Warriors, who are building tiny houses in the path of the Trans Mountain Pipeline in so-called British Columbia, through Secwepemc territory. One of those tiny houses in Blue River is blocking the construction of one of those man camps.

This advocacy is intertwined against fossil fuels, against resource extraction, against colonization and dispossession, but it’s a gender-based analysis against violence that is at the forefront of their concerns, in particular within the construction phase of this industrial development.

CM: Hayden, you write, “Another place where we disagree with the UN global assessment report is the UN is an organization of states that first and foremost defends the territorial integrity of sovereign states; that means that states are the primary vehicle to address climate change and loss of biodiversity. Even while the UN recognizes the harms states perpetuate against Indigenous people, including denying consent, they cannot imagine non-state Indigenous-led solutions that may threaten the state system.”

Hayden, in your opinion, is the number one cause of climate change and threat to the planet—the state?

HK: That’s a tricky question. I wish I could say there was a single cause or a single greatest cause. The state as a political community is really good at holding up particular institutions and individuals with power, and those institutions and individuals often serve capital. The state also helps to organize particular social norms like patriarchy and homophobia. So I would say it’s a central element of a complex.

This is a significant collective action problem that humanity is facing right now, and individual states are pointing fingers at each other instead of working collectively. China is burning too much coal. The Americans have pulled out of the Paris accords. The state inculcates, in communities and individuals, this very nationalist mentality and perspective, and that nationalism blinds us to the work that we have to do collectively as a species—a species with obligations to the land and the water. I think the state as a political community, as an institution, needs to be dismantled, and it’s a huge barrier to addressing climate change.

CM: Shiri, the red paper states, “The matter of Land Back is not merely a matter of justice, rights, or reconciliation. Indigenous jurisdiction can indeed help mitigate the loss of biodiversity and climate crisis.”

Shiri, can giving land back to the Indigenous save us from climate change?

SP: Absolutely. I think it can, and I also think that there is no other way forward at this point. I agree with Hayden that the state is one of the greatest obstacles to meaningful adaptation and mitigation of climate change. But the state is also a colonial actor, so it’s up to people now to reframe where they put their trust and where they’re taking direction—away from the state and towards Indigenous people.

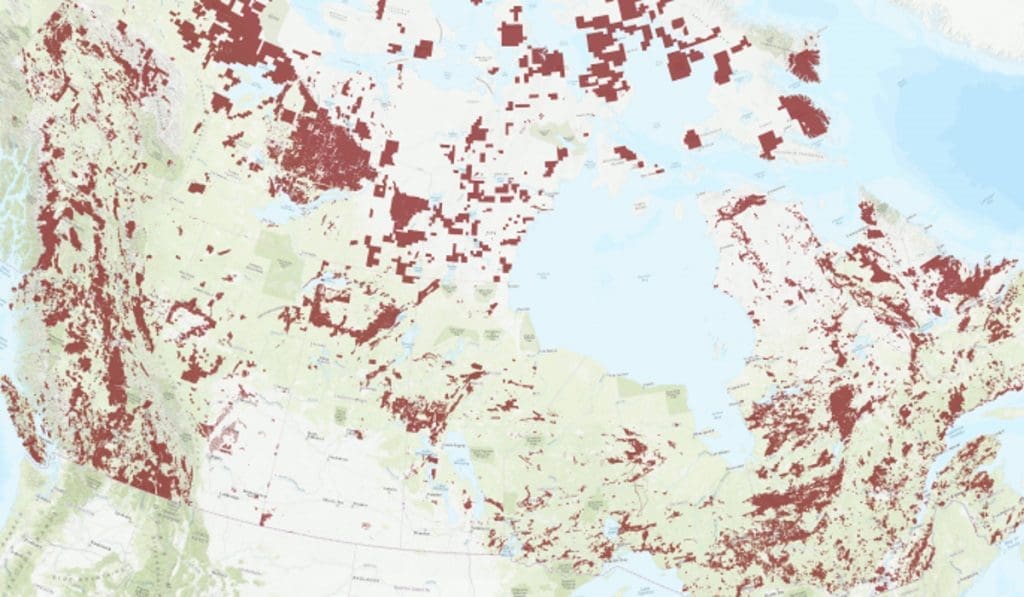

The situation in Canada makes that pretty straightforward for us. We have a situation where the Crown (that is, the federal and provincial governments) claims about 93% of the land base of this gigantic country as Crown land. Most of it is not held as private property, so there wouldn’t be a big issue in terms of land expropriation from private property owners. What the Crown is doing with that land is leasing and permitting and licensing it to resource companies that come and extract these resources—leaving environmental destruction behind, adding to the cumulative impact of decades and centuries of land exploitation, and leaving us to deal with the mess. We’re not even really benefiting economically, in terms of the tax and revenues that come from this extraction.

The time is now for Canadian citizens to rethink their allegiance to the state, and to turn towards Indigenous people and the leadership that they’re showing on the ground to protect their lands and waters, and to follow their lead, and to act in solidarity with them. Indigenous people don’t have to be recognized by the state to have their jurisdiction respected. Canadians at all levels—local and nationally—can recognize Indigenous jurisdiction and defer to Indigenous people in terms of land management protocols and forms of governance.

There really is no one coming to save us. I really feel like the time is now for us to all take a second to recognize our own responsibilities, and to act on them responsibly, and take leadership from Indigenous people at this time.

CM: I want to thank you both for being on the air with us today. Dr. Hayden King and Dr. Shiri Pasternak, thank you for being on our show this week.

SP: Thank you so much.

HK: Miigwech.

Featured image source: Yellowhead Institute