Transcribed from the 4 May 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

What’s critical is not trying to ‘help’ in an unsolicited way, and really making sure that you’re listening.

Chuck Mertz: What happens when the state and the market fail to provide people with the very basics necessary to survive in a time of crisis, when again the government has failed its citizenry? The coronavirus outbreak isn’t the first time people have needed help and the neoliberal government was unwilling to provide services—so this time, at least in Queens, they were prepared.

Here to talk mutual aid and autonomy, Matt Peterson and Maria Herron are members of Woodbine, an experimental hub in Ridgewood, Queens, New York, for “developing the practices, skills, and tools needed to build autonomy.”

Matt is an organizer at Woodbine and is currently helping to coordinate the food pantry. He directed the 2015 documentary Scenes from a Revolt Sustained, and 2018’s Spaces of Exception. Maria is a member of Woodbine and has transformed Mil Mundos, a nearby Brooklyn bookstore, into a mutual aid hub and depot in collaboration with Bushwick Mutual Aid.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Matt.

Matt Peterson: Hey, thanks for having us.

CM: And welcome to This is Hell!, Maria.

Maria Herron: Hi, thanks so much for having us.

CM: Let’s start with you, Matt. It says at the website that Woodbine is a “volunteer-run experimental hub in Ridgewood, Queens for developing the practices, skills, and tools needed to build autonomy.” Let’s start with the very idea of mutual aid, in case people listening do not know what that is. What is mutual aid, and more importantly how does it differ, say, from a state-run social program when it comes to providing food, housing, shelter, whatever is needed to survive daily life?

MP: One of the issues is that at first in the pandemic there weren’t a lot of functional state-run programs. When these disasters happen people have to spontaneously self-organize among themselves and help their neighbors to find information or tools or resources and, in our case, food. Immediately there is a big need for food because people are out of work, they are forced to stay home, and they don’t really want to take the train or the bus, so they didn’t know how to access food. In our case we decided to start a food pantry. Our space is not a food pantry, so we had to spontaneously transform it into one and find supply lines of food with different networks that we were able to build and maintain.

This is an example, for us, of mutual aid: being able to transform our space like this and find supply lines of food—and not just for other people but also for ourselves. We’re also eating this food, because we’re also out of work and precarious and in need, and we’ve been taking on more volunteers, so it’s not just us providing food to other people, but it’s us collectively in our neighborhood figuring out how to maintain the supply line in this crisis.

CM: Matt mentioned the neighborhood, Maria—how is the neighborhood reacting to the work that you are doing? Is your neighborhood a welcoming place? Is it controversial to have your kind of space there? I know that at least here in Chicago (and I’ve heard about other places around the country) where people are providing mutual aid, at times even before the virus, where people are feeding the homeless, there has been pushback either by the community or by the state or law enforcement.

MH: You have to make sure you have the community in mind and the lines of communication have been open from the jump. We’ve found in coordinating with different autonomous spaces—Mil Mundos is kind of an offshoot of Woodbine; being a Woodbine member prompted me to create Mil Mundos for specifically the Latinx and Spanish-speaking community of Bushwick. The response has been overwhelmingly positive. But what’s critical to that is not trying to “help” in an unsolicited way, and really making sure that you’re listening.

At Mil Mundos, a lot of the work that we do with Bushwick Mutual Aid (Woodbine being just over the border in Ridgewood, giving us a really great balance over the two neighborhoods) is in Spanish, and a lot of families that don’t have access to English support systems or have devices at home to fill out a Google forms sheet—they’re just hungry. They just want help. There’s something really critical to just listening to what people need, and this is what prompted Matt and me to start with food and to start with spaces that can function as depots—when people say they need diapers, they need baby food, then that’s what we tell the community, that’s what’s needed. We’re just a liaison at that point.

CM: Let me follow up with you really quickly on that, Maria. There’s always a concern about technological disparity; there might be difficulties for some people to have access to Google docs. How do you make certain to get the message out to your greater community in a way that isn’t limited to only communicating with people electronically?

MH: With Bushwick Mutual Aid specifically, one thing that attracted Mil Mundos to them is that they set up Google voice lines, one in English and one to field Spanish requests. We have a lot of volunteers who work as intake volunteers, and when there’s a missed call we get an email in the corresponding Google inbox, and one of our intake volunteers calls them back. We ask our volunteers if they speak Spanish or are bilingual, if they can translate and help fill out forms. And then there are mutual aid networks to tap into: we’ll get calls from South Ridgewood, people who don’t know who to call who speak Spanish in their neighborhood, and we’re able to connect them to Woodbine, which is closer to them.

Having Google voice numbers has been critical. Fifteen to twenty percent of people are calling from a landline—that’s roughly the number of people who can’t field SMS when we text them to let them know their groceries are here. A lot of people are calling using the same phone number, multiple families calling from one phone number in the same home. And as we’ve found, for a lot of these families, Spanish is their second language. Maybe a version of Quechua is their first, or another Indigenous language. But it’s really revealing the disparity that exists. I think we’re doing a great job of tackling it…for now.

CM: Matt, in an article at Eflux, Woodbine collectively writes, “At Woodbine, an autonomous space and organizing framework we have maintained in New York City since 2014, this is what we have been preparing for, this kind of crisis we are facing right now. To mobilize our network skills, knowledges, and energy to coordinate and provide for each other while simultaneously building the longer-term capacity to face the future.”

Why were you so certain a crisis would happen? If you’ve been preparing for a crisis, why were you so certain it was going to happen? What differentiates you—I hate to say this—from preppers?

We need physical and material infrastructure to provide for ourselves and to provide for other people. Twitter and podcasts aren’t the only ways that people need to organize; people need material things.

MP: I don’t know what the distinction is exactly, but Maria and I are both from New York, and growing up in New York we experienced 9/11 and the financial crisis in 2008, and then hurricane Sandy in 2012, and right now this pandemic is kind of a combination of all three of them. The Occupy movement, which was a delayed response to the financial crisis, was big for us. Obviously hurricane Sandy was a formative experience for us in testing our capacity to self-organize. These are really the things that inspired us to open Woodbine in Ridgewood and self-organize together there.

For the last year or so, as attention has been spent on the election, and a lot more energy on the radical left has been spent on Twitter and social media and things for the screen, we felt that we were becoming a bit anachronistic maintaining a physical space and have all these bills and expenses. It wasn’t until now that we realized this is why we did it this way. This had been our hypothesis all along: we need physical and material infrastructure to provide for ourselves and to provide for other people. Twitter and podcasts aren’t the only ways that people need to organize; people need material things.

This reminded us again of those experiences of the hurricane, of financial crisis, 9/11, these different experiences that we always felt like were going to increase and were going to put people in New York City into more and more precarity. There’s already precarity. When the food pantries first started in Ridgewood around March 10, there were already long lines around the block, but it wasn’t because people had COVID. It’s because people were already food insecure and already needed access to more food. The crisis is exacerbating something that already existed; it’s just bringing a new visibility to it. This is the context within which we’re trying to self-organize, around economic and state dysfunction, collapse, or mismanagement.

CM: You mentioned Occupy Sandy, and Woodbine collectively writes in that Eflux article, “The local experience of hurricane Sandy should also be mentioned, as the immediate response revealed both potentials and limits of a crisis moment like the present. Occupy Sandy was a citywide infrastructure of self-organized disaster relief. After the hurricane struck New York in 2012, some suggested it offered a prefigurative glimpse of disaster communism. However, it could also be argued that the primary function of Occupy Sandy was that of a supplementary service provider within the void left by the state, and that it was never able to become a sustained political formation capable of forcing concessions from the ruling class.”

So Matt, just to follow up on what you were saying, does the work that you are currently doing at Woodbine, and the previous work you did at Occupy Sandy, prove that Occupy was a success? A lot of people argue that Occupy was not a success. Does Occupy continue to this day through mutual aid to provide the services necessary for us to survive under the virus?

MP: Coming out of the response to the financial crisis, there was a traditional organized institutional left—political parties and unions and electoral campaigns and legislative campaigns—and then there was Occupy, which was a bit more subterranean or spontaneous or ad hoc, with people coming together who are not part of those organized forms. Occupy—participating in a process and a model like that—was really transformative for a lot of people, including ourselves.

You saw how that was applied to the hurricane. And now with the mutual aid proliferation throughout New York City and the country, it’s basically like a generalization of Occupy. A lot of these mutual aid hubs, like Woodbine and Mil Mundos and others, look like versions of the encampments during Occupy, where there were a lot of people who didn’t know each other before coming together spontaneously out of nowhere and figuring out how to work together and collaborate and meet needs.

Disasters like a hurricane or an earthquake are localized. They happen in one place and everyone floods to that place and figures out how to work together. Now with the pandemic, it’s generalized. It’s throughout the city, it’s national, and it’s global. It is everywhere simultaneously all at once, and that’s why we’re thinking about networking, what we call disaster confederalism: where, as this goes on, all these mutual aid hubs and groups are going to have to figure out how to collaborate with each other.

This is the alternative or autonomous or subterranean form of organization that I think we’re going to have to see—not just with the medical crisis but with the social and economic crisis that is going to extend for months, if not years.

CM: Maria, in the Eflux article it states that “Woodbine is about deliberating how, if, and when to activate our space as an infrastructural hub within the crisis, beyond the current period of isolation. This will require building relationships and trust to find and become reliable collaborators who can assess their and others’ risk and capacity. We are asking people to think seriously about what this time calls for.”

Maria, how can you build those kinds of relationships under the virus and the isolation that we’re going through right now? Doesn’t sheltering in place undermine most of our ability to organize for a post-virus world?

MH: It can certainly feel that way. But with a space like Woodbine (and we have other friends and comrades who have small businesses or have commercial long-term leases): how do we create spaces, both figuratively and literally, when congregating in person is just not an option? It necessitates a radical re-imagination of how we use these spaces.

For example, both Woodbine and Mil Mundos don’t really allow more than two or three people in the space at a time, but they have become these tremendous warehouses. The conversations that we carry and that we try to engage others in—it’s not just Ridgewood and Bushwick. Now that we’re making it more available online, we’re seeing engagement from around the country and around the world. It’s this kind of space-making: it’s not just space for us, but it’s space for what kinds of conversations we are prioritizing. The silver lining of us all being out of work is that we have some time to prioritize these conversations that we already had a desperate need for beforehand. This is just exacerbating problems that were obviously already here.

How we use our spaces is yet to be written. But the only way that they’re really going to serve us and serve our community is if we’re deciding as a network and as a unit.

Despite what the government is saying, this is going to be a long term situation. Obviously the economic and social effects of it are going to last far longer. For better or worse, people have a lot of time on their hands right now, and they need to be thinking about how they apply themselves to really help other people.

CM: Matt, how sustainable do you think these kinds of networks can, be post-virus? Is there a danger in people feeling that these are only actions that happen during a state of emergency? How sustainable do you think these kinds of networks can remain?

MP: It depends on the relationships we and everyone builds in the midst of this crisis. Our network and friendships came out of the student movement in 2008-9 in New York, and then Occupy, and then Sandy, so we’ve maintained a certain amount of relationships for more than ten years; we’ve been able to sustain Woodbine, and then Mil Mundos is an outgrowth of that. We’re already a testament of people who have passed through different social movements or disasters. And now the sustainability of the project requires more people to get involved, because people have different knowledges and skills and resources, and different networks that can extend to increase supply lines and maintain staffing of the spaces, and have different ideas or networks or contexts about things we can acquire and get. The sustainability is tied into the relationships we’re able to build. It’s not that myself and Maria ourselves are able to maintain these projects or spaces. We need help and we need the energy and commitment and investment of dozens if not hundreds of people as this goes forward.

And I don’t necessarily think the viral crisis is going away any time soon. From what I understand, yesterday was the largest death toll yet in the United States. Despite what the government is saying, it’s going to be a longer term situation. Obviously the economic and social effects of that are going to last far longer. For better or worse, people have a lot of time on their hands right now, and they need to be thinking about how they apply themselves to really help other people.

That’s another big part of mutual aid. A lot of people are sitting at home trying to protect themselves, they’re on Netflix and ordering food delivery, and at some point or another their attention is going to have to shift towards other people. How do they help other people and how do they get involved in projects like this? That’s the only thing that will really sustain any of this.

CM: Matt, how is your supply chain? Are you as impacted as the local stores are when it comes to shortages, particularly of meat and milk, which are reportedly in decreasing supply? Do you face the exact same challenges as any other food supply chain? Or does your farm-share network make it so you can circumvent the more conglomerated, centralized food distribution change?

MP: The pantry is affected by the general supply chain; we have seen a decrease in meat coming in, and we’ve only really been able to provide milk once. But we mostly provide produce, fruits and vegetables. And we get some bread and pasta and rice, things like that. We’re in partnership with a homeless outreach organization called Hungry Monk, and ninety percent of the food comes through that partnership. Recently we’ve been putting pressure on some elected officials in the neighborhood, so they’re finally coming around to help us buy and get more food. But that’s not everything. People still need to buy things like milk and meat—those things we’re not supplying.

But we also separately run a farm-share out of the space in the summer and winter seasons, and this summer’s farm-share is going to be our largest one in the last five years. More than a hundred people have signed up already, which is close to double what it would normally be, and it’s only growing. The farm-share provides vegetables, fruit, meats, dairy, yogurt, and cheese from an organic farm in the Hudson valley just north of the city, and more and more we’re seeing more people wanting to develop their own autonomous supply chains directly from the farmers and the people growing and producing the food.

It’s not that we extra advertised or circulated the farm-share, but when people are going through this disaster they realize they need autonomous sources of food and also want to support local farmers rather than just the traditional supermarkets. This is another exciting, interesting outcome, seeing these networks grow and proliferate.

CM: Maria, in an article at Commune Magazine, Woodbine writes, “The spring of that first year [after hurricane Sandy] is when we started our weekly Sunday dinners, which continued consistently until the arrival of COVID-19 last month. This regular gathering to cook and share food was meant to break out of the dogmatic, professionalizing, and instrumentalizing modes of relation among activists in the city. The idea was that the rhythm and temporality of collective meals maintained consistently for dozens of people on a weekly basis would enrich and deepen both our relationships and the organizational work that came out of them. Collective activities build communities.”

Do these activities—do they need speeches and political power point presentations to teach the audience about the revolution, or is the revolution simply getting people to sit down and share a meal together?

MH: Definitely the latter. Woodbine dinners have continued in this social-distancing era—the first week that we didn’t have dinner, we were kind of shook. This never happens. We always have dinner. People are organizing through Slack and Zoom calls, and at Woodbine we often organize through various networks on Signal, but there were so many people who were so interested in jumping on a shared video call for dinner, people who normally wouldn’t engage—even if there were technical issues, they were like, “Okay, let’s figure it out. How can we still have dinner together?”

So many people are galvanized to make space together. Even if it’s just to have a meal together—not even eating the same thing at this point. Some people aren’t even eating. But just to share space together—Matt or I have hosted some of the dinners since the pandemic started, and then passed it off to other people who may not have felt empowered to facilitate such a thing at first. I’ll say, “I have a call Sunday night, can you host this dinner?” It becomes much more horizontal and autonomous in this way.

For me, the most revolutionary part of that is watching people learn how to carry their own revolutions in their own hearts.

How do you reject the current paradigm while still being held within it? Deprioritizing commerce and capital, and prioritizing mutual aid—prioritizing how someone else is doing. It’s a balance of autonomy and accountability. Who takes care of us? We have to take care of us.

CM: Is the goal, then, Maria, to live outside of the market, outside of the state, outside of capitalism? To live off the grid even if you are living within the grid in Queens?

MH: I think it certainly serves us better. I guess it’s a goal, yes. How do you reject the current paradigm while still being held within it? Deprioritizing commerce, capital, these sorts of things, and prioritizing exactly what we’re talking about, mutual aid—prioritizing how someone else is doing. It’s this balance of autonomy and accountability. Who takes care of us? We have to take care of us.

It helps move things along that everyone is more or less on the same page. It’s not about what people are able to do—a lot of people are like, “Damn, I should have learned how to sew I guess.” Everyone’s cooking a new thing, learning a new skill, watching obscene amounts of YouTube tutorials in this time. But we’re all learning together, and we’re all learning with the main priority in mind of how to take care, how to really deliberately do that to sustain and survive.

CM: Maria, what does it say about the state, what does it say about the market, when mutual aid can do for the public what capitalism and the nation-state cannot?

MH: It says that it’s become a simulation of itself, that it’s dangerously out of touch. I don’t know how obvious those two statements are to your listeners. Sorry if it’s a little plain to say.

For me, the idea of waiting for the governor of my state to “help” me just feels wild. What goes on in media discourse right now is so far from the needs on the street today. People are hungry today. People call and say, “I haven’t had food in two days.” I don’t know how you’re supposed to tell a mother of three who lives with her sisters and their kids to leave their kids to go to a public school to wait for two sandwiches to bring back. It’s so out of touch.

We’re going to get direct deposit money—assuming you’re eligible for a bank account, assuming you have access to these sorts of systems in your language, assuming you have a say at all. Having access—even if it’s in the form of a delivery window, or the steps of Woodbine—just being able to come up to someone who’s handing you food, let’s just start there. You need to be okay for this to be sustainable. We have to first make sure that we’re all okay. Then we can think more long term.

The state is just thinking about economics and the sustainability of the status quo, which wasn’t for everyone in the first place.

CM: You mention the media narrative. CBS Evening News ends every broadcast with a feel good story. It’s usually an individual who has given money to another individual. It’s always an individual story and not about addressing larger systemic issues. I was surprised back in 2012 when Occupy Sandy was getting national news coverage for their amazing mutual aid work.

Why do you think it is that TV news media seems more than willing to celebrate individual actions and work done by “heroes” and seemingly ignores the work that’s being done by tens, hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions, in mutual aid?

MH: If they went that route, it would be acknowledging the failure of a paradigm. With these individual stories, they’re trying to convince people that they have agency within this paradigm. But the most agency people have on their own is to reject it and to go out and work together. There is only so much one person can do. We need help. Me and Matt can’t do this alone. Woodbine and Mil Mundos and Bushwick Mutual Aid, and the mutual aid that goes on with Hungry Monk in Ridgewood—these are massive teams that are working together. There are tens of thousands of people on the same page.

It doesn’t necessarily benefit the media narrative to highlight teamwork in that way. They try to satiate people in the interim: “It’s okay, your small deed is enough.” I don’t know if it’s enough! I don’t see the benefit for the media in highlighting these mutual aid networks. It doesn’t make sense that they would.

CM: Matt, how secretive is mutual aid right now? How much is there a difficulty between wanting to be safe and secure and at the same time have outreach to your community? Because I can imagine that there would eventually be obstacles to this kind of service. Within the nation-state, revolution is illegal. There is no alternative, because it’s illegal to have an alternative.

So how secretive are you right now? Is that an obstacle to getting your services to the people who need them?

MP: It’s the opposite, and that’s one of the big contradictions. We’re being as public as we can possibly be right now with the work we’re doing. On pantry days, hundreds of people line up around the block and there’s nothing that the city or the state can do to say that can’t happen. Effectively we qualify as essential workers, because we’re doing so-called charitable work for those in need. We are not under the stay-at-home orders.

But one of the real contradictions with mutual aid work is when the politicians themselves put out calls for mutual aid, calls for neighbors to help each other: “We all need to step up and do the work.” It’s one thing for me and Maria to talk about, but it feels different when a politician says that. We don’t need you to tell us to do the mutual aid. You should be doing your job and passing legislation and getting state resources to these things. We’ve had some politicians who want to come volunteer with us and have a photo op of them handing out pantry bags. We don’t need you to hand out pantry bags. We need you to figure out how to cancel rent, how to pass legislation that really helps people, how to give people more, how to increase the stimulus packages so people have more income coming in for the months ahead. I don’t think this single $1200 Trump check is gonna get very far. We’ve already seen the rent strikes informally or explicitly on April first or May first. But what about June first, or July first?

Politicians themselves wanting to participate in mutual aid is a direct acknowledgment that their paradigm of governance doesn’t work. Politicians don’t need to be on the food pantry line helping. The whole point of the food pantry line is because the political paradigm has failed, and the economic system as failed. We don’t need you to volunteer to come help us prove that. The reason we’re doing this work so publicly is precisely to prove and demonstrate that this needs to happen more and more, just like it happened in the hurricane and after the financial crisis. People need to self-organize, because the government and the economy are not functional, even in normal times, in providing for the needs that they are supposedly organized to do, and this is just proving that and bringing that to greater visibility.

That’s the opportunity that we’re living in right now, seeing all these structural contradictions made manifest.

CM: Matt, to what extent does that kind of self-organizing, that kind of parallel state, prove to those who are libertarian, or pro-business, that everybody can take care of themselves and therefore we don’t need social security, we don’t need safety nets, we don’t need universal healthcare, everything will take care of itself? How much is there a fear that that kind of self-organization will prove libertarians correct?

MP: One of the reasons we talk about dual power is to recognize that there’s different forms of power existing already in how the world works, and while we’re doing mutual aid work, we’re using it as an opportunity to put pressure on the government and local elected officials. They’ve already been forced to step up, out of embarrassment or shame, to find us more masks, more PPE, more food, because it’s clear to so many hundreds of people that we’re providing a greater service than they are.

They don’t see or hear anything from the elected officials. The work of mutual aid should be a force to put pressure and leverage on the government and elected officials—more than just totally seceding, we need more help from them. We need rent legislation. We need more stimulus money. We need more things. By self-organizing, it’s not to totally leave social security, but to put more pressure on it. They can’t just exist without us.

CM: Maria, is Woodbine, Mil Mundos and Bushwick Mutual Aid all a communist conspiracy? And Maria, would you feed a fascist?

MH: No.

CM: Thank you so much for being on our show, Matt and Maria.

MP: Thank you.

MH: Thank you so much.

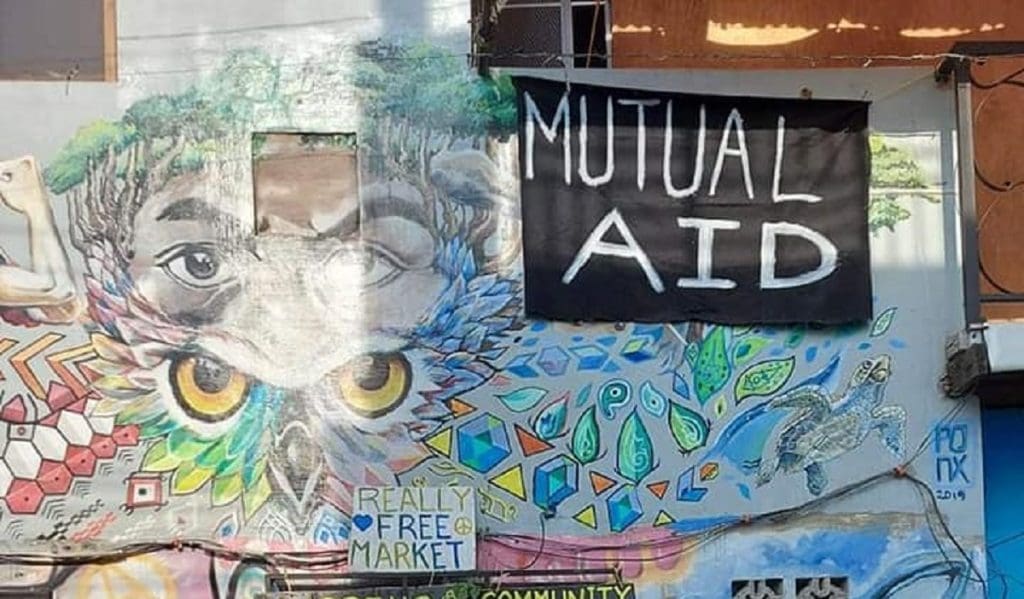

Featured image source: Etniko Bandido Infoshop (Philippines), via Enough Is Enough (Germany)