Transcribed from the 30 March 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Class-based rage is an overlying theme, and something that is often under-examined in regard to women’s anger at the world. Women live in conditions that are just fundamentally different, often, than men.

Chuck Mertz: Feminist manifestos are rude, they are crude, they speak impolitely, they yell and scream—and are unfairly dismissed, even by liberal feminism. Here to tell us about the power of the feminist manifesto, professor of women’s and gender studies at Arizona State University, Breanne Fahs is editor of the collection Burn it Down: Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Breanne.

Breanne Fahs: Thank you so much for having me.

CM: You start by citing Valerie Solanas’s 1967 SCUM Manifesto, which you say is one of the “all-time great declarations of war against the patriarchal status quo.” Solanas writes, “Life in this society being at best an utter bore, and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

I’m on board with most of that (the destroy-the-male-sex part I’m not too sure about). Why do you think that is one of the all-time great declarations among feminist manifestos? Why is this a great declaration of war to you, and has it be come more, or less, relevant over time?

BF: Valerie Solanas is one of those wonderful characters who continues to plague people with questions. Was she serious? Was she writing a satirical document? People still don’t really know. People thought it was satire—then she shot Andy Warhol and people changed their minds. Whether this was a document where she meant it to be completely serious or not, people don’t know. I think it’s a wonderful document no matter how you read it.

Sometimes it feels like a document of humor, sometimes it feels like a declaration of war. Great manifestos do that. They come alive in different historical moments. They go dormant sometimes, and then you read them again a year later and suddenly they’re magical and alive again.

This manifesto really embodies everything that feminist manifestos often are: absolutely unapologetic, militant, forward, not allowing any room for anyone to disagree. They are really unusual documents in that way. They are declarations of revolution.

CM: What makes a manifesto a manifesto? Is it just because the authors themselves called it a manifesto? In that way, is a manifesto like art? If an artist calls it art, it’s art.

BF: A manifesto is a revolutionary document that isn’t very careful in the way that it speaks. The tone is very often combative or aggressive. It has a very distinct way of not making room for counterarguments. It doesn’t cite things. It’s very different than other kinds of scholarly documents or creative writing. It has a lot of very strong emotion right on the surface of it.

This is quite different from the more dispassionate forms of writing. Manifestos don’t mind being hot-tempered and angry and of-the-moment. They are supposed to feel like someone threw them out of a window and they smashed all over the place—that’s the vibe they’re supposed to have.

Often they speak to various immediate concerns that are happening right in that cultural moment. They’re not meant to be documents that last forever or that speak to people forever, although a lot of them, interestingly, do come to feel that way over time.

It’s a tricky genre, because it doesn’t necessarily have a super specific form. But the emotionality, the revolutionary intention, the anger, and the sense that things urgently need to change are all very consistent throughout them.

CM: You were saying that they’re not necessarily welcoming to critique, but does that mean that manifestos are above criticism?

BF: No, but we want to take them for what they are. When we’re looking at something like class-based rage, we want that to be able to exist without critiquing it in the ways we would other kinds of documents: “You’re not thinking about this with enough historical context,” or “You haven’t cited your sources.” These are not things we would apply to a document that is a manifesto.

Manifestos are really about breaking free of something in the old world order and making something new. They’re trying to break ground. In that sense, to the extent that they’re successful in doing that, maybe we could critique them—or to the extent that they produce an emotional reaction in us as readers, maybe we can critique them. But it doesn’t come with the same set of critiques that we would have for other kinds of documents.

CM: You cite Valerie Solanas again writing in the SCUM Manifesto, saying that her manifesto is “for those in the gutter: whores, dykes, criminals, and homicidal maniacs wholly refusing to pander to nice, passive, accepting, cultivated, polite, dignified, subdued, dependent, scared, mindless, insecure, approval-seeking daddy’s girls.”

Are feminist manifestos then, necessarily, class manifestos?

BF: I think so. That’s a subtext that runs through this whole book: women thinking about what it means to live in the gutter, what it means to live without as many resources as others. Class-based rage is an overlying theme here, and something that is often under-examined in regard to women’s anger at the world. Women live in conditions that are just fundamentally different, often, than men. That is a narrative that runs through this.

I love that thing that Valerie Solanas said about who the manifesto is for, because this collection feels like that too. This collection is not just for a small, elite, well-educated audience only. There’s something in here for people who often don’t feel like they can access themselves in books at all. This book is meant for people who are feeling marginalized or lonely or who don’t feel like their voices have a home. There are writers in here who have never had their words published at all, anywhere. There are writers who are talking about very unsexy themes like severe poverty and violence and rage.

Not only is that an ethos that runs through the book, but this book itself is designed to be accessible and speak to people in different ways than most books do.

We’re in the middle of this pandemic crisis. There’s a sense of despair and depression sinking in. Soon enough, there will be a huge emergence of collective anger, if we play our cards right, and that has to be valued.

CM: Is feminism a class project? And does feminism being a class project mean that it is not only for those who identify as women? Is feminism only for and about women? Or is this more about everybody, as a class project?

BF: This is a question that I hear a lot, and it’s tricky. There are lots of different versions and styles of feminism. Feminism is not something I can wholly define for listeners and readers. At the same time, if feminism links up with class-based struggle, then of course it has more implications than just for women themselves. Feminism is something that demands attention from everyone, and should demand attention from everyone.

The more people suffer under the system of capitalism, the more a feminist critique is needed as well. We want to see that link, and we want to see that all the time in people’s minds. There is no such thing as not joining the feminist struggle, if you care about class struggle.

CM: You point out that “the validation of women’s anger in the late 1960s, a cultural zeitgeist moment that recognized women as finally fed up and truly enraged, made it possible for women to push back against cultural pressures for politeness and respectability.”

Today we hear concerns over a lack of civility when it comes to protesters and activists and the demands they have for change. What does it say about being polite or respectful or civil, when struggling for rights seemingly upsets all of those societal customs?

BF: That is a common way of undermining radical movements, and social movements in general. I’m all for a complete rebellion against the notion of politeness and respectability. Those are just funnels that try to consolidate power, that push a more elite way of thinking or functioning, that disempower people.

Politeness has been tinged with gender norms and gender roles for ages and ages. It’s something that disallows women of their own anger; it strips people of their sense solidarity with others. I’ve heard this hesitation a lot: “We can’t hate the rich, because hatred is bad for us.” I couldn’t disagree more. When we have anger and rage and radicalism and are pushing back against politeness and respectability, we are doing that from a fundamental, deep-seated place of love, or hope for what our country could be, or what humanness could be.

It’s not coming from a place of apathy that people feel those things. It’s coming from quite the opposite. We’ve created this false binary where lack of civility, hatred, anger, taking to the streets, or radical protest is seen as the opposite of feeling fundamental deep-seated love for fellow humans. That’s just not true.

In this collection there is so much validation of women’s anger and its potential for being a very revolutionary thing, and for helping us to see ourselves and find ourselves there. In this cultural moment—we’re in the middle of this pandemic crisis. There’s a sense of despair and depression sinking in. Soon enough, there will be a huge emergence of collective anger, if we play our cards right, and that has to be valued.

We can’t have that under the guise of politeness and respectability. That’s not going to be how this goes. That’s not going to get people what they need to get through this.

CM: Many of the different manifestos that you have in this collection are collectively written. In doing your research, did you find that to be more common with feminist manifestos? What does it reveal about feminism when so many of these manifestos are written collectively?

BF: I love that. It really pushes back against the idea of some individual in a tortured state writing a manifesto alone in a room. This is not how many of these are written at all. These are written by people who don’t even want to take credit with their names. They want the manifesto to have the name of their underground group or their collective sometimes. It’s a really important feature of feminist manifestos that there are people working together to create a vision for a new world or for what could be possible.

It is absolutely important for us to think in those terms as much as possible: What is possible? That is one of the levels on which we are often impoverished: not to be able to think about new possibilities, or to be stripped of our sense that it’s even something we’re allowed to do. A lot of these groups of women are sitting down trying to think together about what is possible, and I can’t think of almost anything that I find more powerful and important than that.

CM: You write, “Manifestos pry open the eyes we would rather shut, forcing us to reckon with the scummy, dirty, awful truths we would rather not face.”

If manifestos do open our eyes to the ugly truth about the world, what impact does that have on their popularity and acceptance? Is that what makes them unpopular?

BF: I’ve had many people tell me they didn’t even know there was such a thing as a feminist manifesto. Many people have heard of the Communist Manifesto, or some other big classic manifestos. They often haven’t heard of other kinds of manifestos with a more strongly feminist overlay.

It’s true that when we’re dealing with a genre that is overtly emotional, it is frowned upon—especially within the academy. It always enrages me that you’re not supposed to teach or write or interact with documents that are on the surface level very emotional. That degrading of writing that is impassioned and emotional is also part of how we’re trained not to take these things seriously, or even to resist them.

There’s something about this collection—look at it as a whole. Even the manifestos that frankly disagree with each other, you find them compelling somehow. There are ones that, even if you hate them, are interesting. They are provocative, and they definitely make you think about your own politics and the limits of those politics. I don’t write myself out of that. Sometimes even for me, reading manifestos can be unpleasant. It’s almost as if you have to wince when people are talking in this way. It takes a lot to steel yourself to read these.

At the same time, at the other end of it, when people speak the truth about themselves and the world, you feel like you can breathe again, there’s oxygen. Even if it’s something that you don’t initially like, it’s really powerful and important.

Maybe people have come across a manifesto here and there, or they’ve read one or two, but they haven’t really thought about how manifestos function as a body of work, or how they can be a testament to an entire hundred-year history of the ways people have been thinking.

CM: You point out how feminist manifestos travel in time and space. Your collection includes stuff going back to Sojourner Truth, from 1851 up until 2018. You have a wide variety of diverse views. And we were talking about timeliness and timelessness. Last August we spoke with Bathsheba Demuth, author of Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait. Bathsheba explained how European political economic systems do not work in the region around the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia, because they cannot be sustained by the agricultural or manufacturing capability there. American capitalism, Western European socialism, and Soviet communism all have failed there. None of those systems really work in Beringia.

Can the same be said of feminism? In your study, did you find different feminist manifestos with different feminisms based not just on time but on space, or based on the author being somebody who is a white European as opposed to somebody who is Indigenous?

BF: Sure. When we look globally at how manifestos travel, and the ways people are thinking, context definitely matters. Look at South African feminism, which has a long history of being wonderfully radical and militant. They don’t have nearly the same hesitation around it that we find in the US and Western European feminism. There are many different variations between regions.

Of course we would be remiss if we don’t look at ourselves. US politics often embrace the liberal at the expense of the radical. You see that in the ways manifestos enter the scene and are rejected, or are regarded as useful or useless. Teaching manifestos in a classroom can be really tricky. People react to them differently than other kinds of documents. Their emotional experience of reading them, or of you teaching them, is quite different.

What’s wonderful about them is that people are writing from the space and place and time and context that they’re in. You really get a sense of what it means to become radicalized in your own time and place. We’re seeing that right now. I can’t imagine that this experience we’re all going through doesn’t have the potential to be very radicalizing for a lot of people. The virus will inform the way people experience their politics for a long time.

CM: You write about how in 1775, the idea of the manifesto was a top-down order from government, imposing something upon the people. And then the people took the authoritative voice found in manifestos, and turned it back on the government. It turned into a document of rebellion.

Can that kind of co-optation work again in reverse? Can corporations, can capital again try to co-opt or take control over the idea of a manifesto, and again rebrand that manifesto and that revolutionary voice for their own profit-seeking? How easily or how well can that kind of corporate co-optation take place?

BF: They’re trying. There’s a brand of wine called “Manifesto,” that has these catchy sayings on the side, or brands of jeans that are using the word. You see the world manifesto used in car commercials. It is quite alarming and disturbing how much people take this word to sell things or to be cool, to appeal to some kind of rich hipster demographic.

But manifestos are good at pushing back against that. They feel like they don’t have sticking power in that way. Manifestos are the screaming that happens in a particular moment. They can have resonance later on, but they don’t really work as a corporate co-optation. It ends up looking more laughable and pathetic than effective—at least in my view. Although honestly I don’t think we will ever see corporations stop trying to use them as a way to sell or market things.

We always have to worry about staying one step ahead of co-optation. Even when I write about women’s sexuality, which is another theme that I work on in my academic writing, I’m always saying that. Co-optation of resistance movements is always coming, and you have to try to stay one step ahead. That’s the best we can do. We will never be free of the politics of co-optation.

Everything that we label as cutting edge—consider “sexual freedom”—will be coopted in a negative way one minute later, and we have to then try to reimagine those politics again, trying to stay one step ahead. We saw this with the politics of the orgasm. It was a huge important part of the sexual revolution that women were allowed to have orgasms, and then one generation later, huge percentages of women are saying that they’re faking orgasms.

You have to stay one step ahead of what the rhetorics of sexual liberation and other kinds of liberation mean. Same with manifestos. We want to always stay one step ahead of what those co-optive politics look like or feel like. But they will be coming for us. They always are.

CM: You point out that your book is not about legitimizing the manifestos you’ve included, but having people think about why they have been dismissed. Why is it so important to consider why these manifestos have been dismissed, while reading them?

BF: We just don’t give manifestos a fair shake. People don’t even understand that manifestos comprise entire bodies of work. Maybe people have come across a manifesto here and there, or they’ve read one or two, but they haven’t really thought about how manifestos function as a body of work, or how they can be a testament to an entire hundred-year history of the ways people have been thinking.

The notion of writing from the gutter or thinking about trashiness has a whole body of work around it. Queer and trans manifestos—the history of radical queer movements and the manifesto writing within that—is a body of work that we can look at and consider. Part of not dismissing them is looking at them collectively, looking at groups of manifestos and digesting them in that way. It helps to imagine that resistance has always been there, and that people have been fighting these fights for much longer than we consciously realize.

CM: One of the manifestos you include is the Alt-Woke Manifesto, which was written by anonymous authors. It states, “There is no term more ubiquitous, obnoxious, and self-serving in our current lexicon than woke. Woke is safety-pin politics, masturbatory symbolism, and virtue-signaling of a deflated left insulated by algorithms, filter bubbles, and browser extensions that replace pictures of Donald Trump with Pinterest recipes. Woke is a misnomer—it’s actually asleep and myopic. Woke is a safe space for the easily distracted and defensive pop culture inbred. Woke is the left curled up in a fetal ball scribbling thinkpieces about Broad City while its rights get trampled by ascendant fascism, domestically and globally.”

That’s the great thing about all these essays. At certain points I’m really angry and then two words later in the same sentence I’m laughing. How common is it for feminist manifestos to target the liberalism of what it means to be “woke,” engaged in by those who believe they are doing the right thing as opposed to those who are intentionally and purposely doing the wrong thing? How often is it criticizing those who may be well-intentioned and not necessarily those who are directly opposed to what those manifestos believe in?

BF: The divide and distinction between liberal politics and radical politics is crucial. Often people don’t understand that radical does not mean “extreme.” It means digging into the root structures of a thing. This is a radical critique of woke politics. They’re trying to say: we cannot stay with these superficial, surface-level, within-the-system forms of change. Those don’t mean anything. This is a hollow signifier. What we need is a much deeper analysis of the root structures of why we’re all screwed.

It’s a great manifesto for embodying the difference between liberal and radical politics. Liberal politics are trying to work within the existing structures and the existing systems. Radical politics are trying to dig underneath the surface and start anew, trying to build something else. That has gotten lost in the shuffle. We’ve misused the word radical, thinking that anything extreme is radical. No. Radical is doing a deeper-level dig-into-the-roots analysis of oppression, misery—of everything.

Almost every woman on the planet has been accused of being “too much” in their emotions or their anger. In the manifesto genre, people are too much on purpose.

I love this manifesto too, and you’re absolutely right: Sometimes when you’re reading them and you feel like they are saying things that are true, you can’t help but laugh. Not because you’re dismissing them, but because that’s where great humor comes from. Humor comes from the place of people saying things that we know are true. I have that reaction to many of these manifestos, including the SCUM Manifesto. They are profoundly funny in addition to being deeply true.

CM: Is “being woke” a capitalist-friendly version of antiracism? Are well-intended actions undermining the fight against racism and misogyny and patriarchy? Or is wokeness—and even liberal feminism, for that matter—at least a step in the right direction?

BF: I take the position that James Baldwin often argued, which is that there is almost nothing more dangerous than the well-intentioned liberal. Well-intentioned people who follow a within-the-system form of change will often say things like, “Well, we need this first, and then we’ll get to the more radical critique or the radical politics later,” or “We just need to be patient and wait for change to come,” or “You know, we want to take it slow and step-by-step and we can’t think in big sweeping ways.”

That’s super dangerous. For many of your listeners it will be very obvious why. We don’t want to dismiss liberal feminism or wokeness entirely, but we do need to be extremely aware of how dangerous some of these rhetorics are if our overarching goals are getting at a bigger, more powerful and lasting form of social change.

It’s never good when people are doing the “Let’s take it slow, let’s wait and see, let’s take the lesser of two evils, moderate perspectives are good” thing. We’ve seen the hazards of that in such technicolor detail, both lately and historically, that I can’t imagine we’re not a little bit more wary of it by now. This collection is really an effort to focus our attention on what it means to think in bigger sweeping terms. What does it mean when individuals who we ordinarily strip of the power to do that are empowered to think in these ways, and tell us their worldviews? We need radical feminism. It is the way forward. Radical politics in general are the way forward.

CM: ANON writes in the Alt-Woke Manifesto, “The moderate midwifed the birth of the alt-right through bipartisan compromises. Moderate liberals are basically content to vest trust in their vaunted Democratic Party as it slides further to the right, thereby underpinning a level of discourse friendly to the far right. It’s worth remembering that the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first centuries were a period of die-hard cooperation between liberals and conservatives in crafting today’s authoritarianism.”

Does liberal feminism also give cover for the rise of the more far-right misogynistic types who flourish within the alt-right? Is that another problem with liberal feminism, that it gives cover for the far right?

BF: It’s possible. Arguments like “Make sure you work within the system” fundamentally validate the system and the rightness of that system. The system itself becomes the container in which you can shuffle things around, but the shape of that container never changes. Validating the rightness of that container, that system, gives way to all sorts of things that we may not intend.

A well-intentioned liberal is well-intentioned. I don’t doubt that. People want the best for each other, and they feel like moderate politics are the way to go, and they mean that sincerely. But when we validate the system as it is—whether that’s our electoral system or the current economic system—that can lead to really insidious, problematic results, not the least of which is the rise of the alt-right.

I don’t want to come across as dismissing all of it completely. But we want to try to remember that when we move in a more radical direction, people are more likely to win than when we don’t.

CM: You write, “For feminists, the manifesto became an ideal mode of communication, as women usurped power typically reserved for men, expressed rage and anger typically denied to them, and sought revolutionary goals and principles. Within the manifesto genre, they could be mad.”

Why were women allowed to be mad within the context of a manifesto but not outside of that manifesto? And why is it so important to be mad?

BF: I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to validate women’s anger, and what it has the potential to do. Think of all the ways women, in their normal daily lives (and this is not just here in the US but throughout the world), are stripped of both individual and collective forms of anger. It is devastating. There’s a pressure within feminism for women to feel like their feminist politics always have to make people feel comfortable or at ease; they adopt a feminism-is-for-everybody approach. “I’m not really that threatening, I’m not really that angry, I’m not that disgusted with patriarchy.” I’m not this or I’m not that—people are disavowing identities that they think are scary or less palatable.

Manifestos are doing the opposite. They are not in any way trying to make people feel more comfortable or more at ease. We see the real transformative potential of anger. Women do feel anger, they just don’t express it a lot. And they feel it in all sorts of ways. We see that now in the ways that women are trapped in their homes with their families, and they’re starting to realize, “I thought I had come a long way in regard to my politics of domestic work, and now I am responsible for taking care of all my kids and my partner…”

Women’s anger functions in potentially transformative ways which often go under the radar. Manifestos bring it to the fore: they use emotionality, and all the things that women are accused of that they often try to take distance from, like being “too much.” Women are always accused of being too much. Almost every woman on the planet has been accused of being “too much” in their emotions or their anger. In the manifesto genre, people are too much on purpose.

CM: You write, “Who gets to say things also changes and shifts with manifestos. Manifestos are more often found than they are officially published, giving then an ephemeral, unedited, and immediate feel. Once mostly the domain of the art world, manifestos at their core want to radically upend and subvert public consciousness around disempowerment, giving voice to those stripped of social and political power.”

Back in March of 2017, we spoke with Jessa Crispin about her book Why I Am Not a Feminist: A Feminist Manifesto, which is featured in your collection. Last year we spoke with Cinzia Arruzza about Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto, which she co-authored with Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser.

To what extent does the fact that those are officially, commercially published limit their ability to be true manifestos?

BF: The contradiction here cannot be minimized. I feel like this all the time when I teach manifestos within the context of the academy as well. It’s completely bizarre. I’m teaching these documents that are meant to be anti-institutional and revolutionary and activist in nature. And I’m doing it within the hallowed walls of the academy. Same with this book: trying to corral these manifestos into a book is a profound irony that is not lost on me. They are wild animals. These manifestos are in some ways not meant to be corralled. Doing so is a weird contradiction.

I felt that also when writing the biography of Valerie Solanas. That was a very weird thing to try to do. So many aspects of her life and her persona are about being firmly against the idea of someone else telling her story.

The best we can do is live with those contradictions and try to do right by the work as much as possible, and feel shitty about it sometimes, and not minimize that in any way. There’s no point in minimizing that. My hope is that this book will be passed from person to person or obtained by any means necessary, quite honestly, to be used by whoever needs it. But there’s no way to feel totally comfortable or settled with that. This is a document that contains things that aren’t really containable. It’s an unresolvable contradiction that we have to work with.

CM: Thank you very much for being on our show this week.

BF: Thank you.

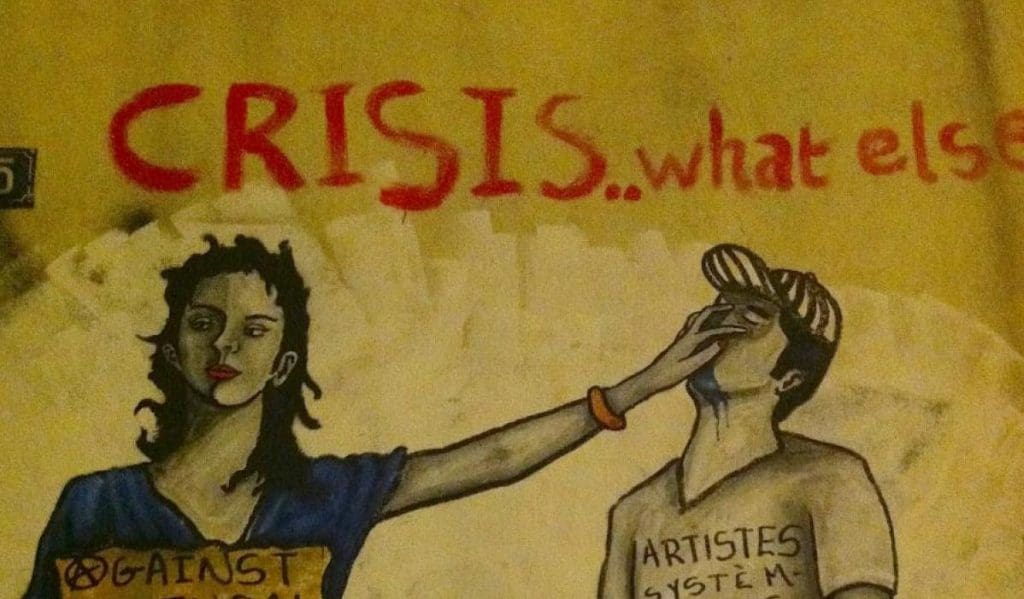

Featured image: Street art in Athens, Greece ca. 2013