Transcribed from the 10 August 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The “new Cold War” paradigm, which is being amplified both by global elites and so-called anti-imperialist writers, does not benefit the left at all and has totally opposite goals from international solidarity. State elites, from China to the United States, are connected.

Chuck Mertz: Many on the left outside Hong Kong see the protests there as supporting the US or President Trump, or being created by the CIA as a covert operation, or a US project to wrest control of Hong Kong away from China and build up to a larger military confrontation. This is far different from what our guests see in the protests: a movement against colonialism, imperialism, and capital interests that drive state violence.

Here to explain, members of the Lausan collective, Andi W. and Promise Li wrote the Tempest magazine article “Left on an Island: Hong Kong, China, and International Solidarity.” Andi is an organizer and writer based in northern California. Promise is a socialist activist from Hong Kong and Los Angeles, a member of Lausan collective, Solidarity US, and also of the Democratic Socialists of America, and a former tenant organizer in Los Angeles’s Chinatown.

First, welcome to This is Hell!, Andi.

Andi W: Thank you, happy to be here.

CM: And welcome to This is Hell!, Promise.

Promise Li: Hi, thanks for inviting me.

CM: The editors of Tempest write, “For the US left, rather than international class solidarity as a starting point, campist politics have increasingly come to the fore.” What is meant by ‘campist’ politics, and to you, what explains those campist politics being prioritized by the US left over any international class solidarity?

PL: I think the story begins before the Hong Kong movement. In the last couple years, especially since the Syrian revolution, there has been increasingly a sphere of the so-called “anti-imperialist” left that’s been blatantly disseminating disinformation—and claims to support and apologizes for the worst authoritarian rightwing regimes as long as they seem sufficiently opposed to the US.

With the Hong Kong movement, outlets like Grayzone and writers like Ben Norton and Max Blumenthal have been at the center of this basically rightwing disinformation campaign where, despite their rhetoric, they amplify the US-China “new Cold War” dynamic that polarizes world geopolitics into two camps. That’s really following the dictates and demands and desires of the global state elites. That doesn’t benefit the international working class at all.

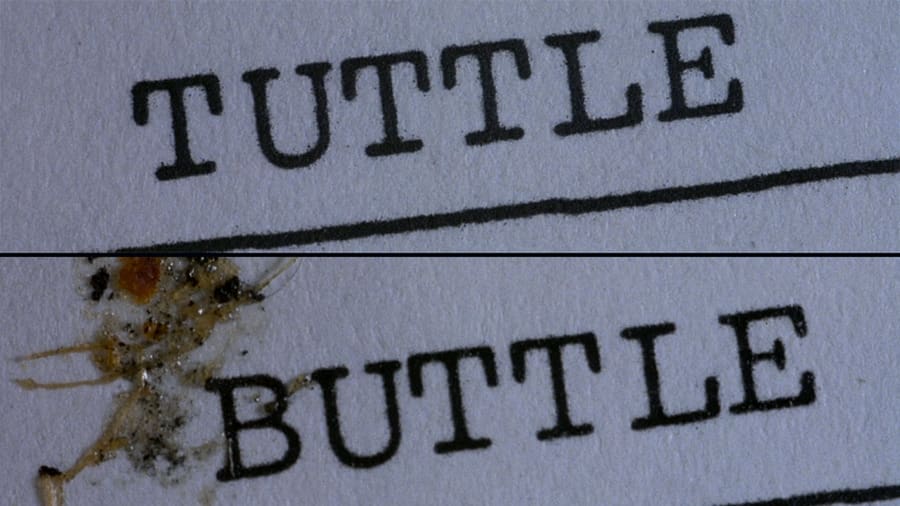

Lausan’s intervention, and our piece’s intervention, is not just saying “Actually, China is worse” or is just as bad as the United States, but establishes the fact that this “new Cold War” paradigm, which is being amplified both by global elites and so-called anti-imperialist writers, does not benefit the left at all and has totally opposite goals from international solidarity. State elites, from China to the United States, are connected—in terms of capital investments, in terms of policing exchanges, all these things. It’s US-made and UK-made teargas being deployed against protesters in Hong Kong, alongside Chinese-made teargas.

There’s no better symbol to talk about how different forms of state repression are connected with each other. Mass movements need to link up together too, and resist the new Cold War dynamics that are being pushed on us both by people we usually fight against as well as people on the left spouting disinformation campaigns.

CM: Let me follow up with you on that, Promise. You compare that to what is taking place when it comes to left criticism vis-a-vis Syria. The US is likely having some impact on the protests in Hong Kong; they likely had some impact on what was taking place in Syria—the CIA is likely doing something in both those places. Is any role the US might have in Hong Kong’s protests being exaggerated? Whenever I see someone mentioning the Hong Kong protests online, they’re shot down as naive.

Why do you think any role the CIA or the US is playing in the Hong Kong protests may be exaggerated, and why does the US left (or the left outside the US) exaggerate that presence and that role?

PL: The first question I usually pose to these “leftists” is what right they have to judge these movements, requiring morally pure protesters of some kind who aren’t supposed to take any sort of aid. Of course, the Lausan collective opposes any kind of US intervention, and we recognize the catastrophic history of US interventions and foreign policy. At the same time, yes, I think it’s true that the National Endowment for Democracy and other groups have poured money into some trade unions and other groups—but the narrative that gets covered up is the Chinese government majorly courting US investments and US interests for decades before what’s happened in the last year. China’s own rise to power is predicated on superexploiting its own working class and exposing them to Western consumer markets for cheap labor and low prices as it continues to extract. People tout China as the progressive alternative to the West, but in reality it’s slotting itself into an existing world system that’s governed by imperial relations.

US law enforcement trained Hong Kong police officers for years. US teargas is being deployed—Pennsylvania-made teargas is being deployed on the streets of Hong Kong. The problem isn’t that the people who support the Hong Kong protests aren’t anti-imperialist enough. The problem is a selective critique of US imperialism ignoring that the Beijing government also systematically courts these interests, and at a rate that all these supposedly pro-US protesters with NED funding can barely rival.

As leftists, we struggle with very complex mass movements wherever we are. The examples I like to use are the Black Lives Matter movement, or the movement against Trump in the last four years: they’ve been joined by some conservatives, liberals, and NGOs, right? People we usually fight against as the left—but we’re forced to the same side against a common cause. We don’t like that, and as leftist organizers we must out-organize that. But it doesn’t mean we smear and write off the whole movement. I think the same logic applies to Hong Kong.

The way forward as leftists is to provide and model alternatives that we can concretely give to the movement. Now that repression is getting stronger and the situation on the ground is more dire, this is precisely the moment for the left to think clearly again. It’s all been either ignorance or condescension so far.

CM: Andi, you and Promise write, “Standing in solidarity with Hong Kong is not about deciding which nation-state is worse. It’s about rejecting this false binary the ruling elites have crafted for us, and resisting the spread and adoption of Western colonial frameworks by all states alike, especially China.”

How do ruling elites from both sides—from the Chinese side and the American side—benefit from this false binary? And in your opinion, why do you think the left here in the United States falls for this false binary?

AW: Passive aggressions by Beijing have been matched and intensified by the belligerent language of the Trump administration in Washington. It reflects a new Cold War rhetoric, a polarized worldview that obscures a global neoliberal consensus of oppression of everyday working class people. “Neither Washington nor Beijing” doesn’t simply signal that both states are equally bad, but it recognizes that imperialism is a world system not limited to the boundaries of nation-states. That way, Hong Kong protesters and their supporters are in a position to reject new rising imperial actors that reinforce the global system of inequitable relations.

Furthermore, even Trump and his far-right supporters have ignored the situation in Xinjiang and Hong Kong when the trade war ebbs between China and the US.

CM: People watch Fox News and they see people at the protests waving American flags. They see people at the protests asking president Trump for help. They hear about protesters asking the US congress for help. All of those things, according to many viewers and skeptics, prove to them that this is a pro-Trump, pro-US protest in Hong Kong.

Why do you believe those images may not be an accurate representation of the protesters as a whole, Andi?

AW: Because those symbols don’t represent the interests of all Hong Kongers. In the media, we see symbols such as the US flag or even banners asking for Trump’s help, but that doesn’t represent everyone’s interest. The Hong Kong movement includes elements from across the political spectrum. This does not invalidate the struggle against Beijing’s state violence.

The appearance of reactionary, xenophobic, US-flag-waving elements in the protests should definitely be condemned. But the rejection of such elements is not an excuse for supporting or choosing to remain silent about the Chinese state which has clearly courted US interests on a scale much larger than pro-US-intervention Hong Kong protesters like Joshua Wong or Nathan Law.

CM: So Promise, how bad is Fox News channel’s coverage of the protests in Hong Kong? How bad are they for the democracy movement that they claim to be supporting? How much does their focus on far-right reactionaries in the crowds at Hong Kong protests undermine any left solidarity, and undermine the protests that Fox News is supposedly supporting?

PL: That coverage is very destructive for the movement, and very destructive for left solidarity. One factor that is important to point out is that these people have been the first and most vocal, speaking in support of the Hong Kong movement. The Hong Kong movement did not have substantial international connections, and this whole past year has been a fast track for Hong Kong protesters getting a grasp of what global geopolitics are like.

Another point we mention is that the left-right political spectrum doesn’t exactly track in Hong Kong. There’s not a tradition or history of speaking about politics in those terms. The Chinese communist party, which is an authoritarian state force of repression, has monopolized what it means to be ‘left,’ for multiple generations of protesters. That in itself really muddles things a lot.

When folks in Hong Kong are trying to think about global solidarity, and are desperately trying to find international allies—as they’re trying to learn about global politics and what this left-right thing even means—what they see is that the right has been the most vocally supportive. That makes sense to us in the United States: the right has always had a vested interest in pushing for US intervention, unjustly and destructively, in other countries. They have a whole infrastructure to push out this type of rhetoric. Pragmatically speaking, the so-called left here has been either silent or actively demonizing them. People see that.

Ideologically speaking, the Fox News coverage is very destructive, but I think the left needs to wake up and pay attention to the fact that if we’re not going to extend solidarity, if we’re not going to have and model practical alternatives for what it means to provide a progressive, leftist international solidarity paradigm for Hong Kong protesters, it’s only natural for these people to look to the right, standing there in support throughout the year.

So not only is the coverage bad, but there are a minority of protesters on the ground who are actively courting Fox News and rightwingers. The way forward is to condemn these elements, not to completely smear the movement. The way forward as leftists is to provide and model alternatives that we can concretely give to the movement. We have tons of resources at our disposal—not only material resources but political and educational ones: unions and civil society groups, student groups. The left has always been at the forefront of organizing these mass movements and groups, and a lot of these alternatives are not being explored—partly because of the disinformation and muddying from some of these outlets.

Now that repression is getting stronger and the situation on the ground is more dire, this is precisely the moment for the left to think clearly again. It’s all been either ignorance or condescension towards what’s going on in China and Hong Kong: speaking over protesters, not really believing in the right of mass movements to fight for liberation. The left needs to wake up and find its place again, and discover what it means to provide the kind of support that’s always been in the traditions and history of activism.

CM: Andi, Promise was just saying how the repression keeps getting stronger, even during the pandemic. The two of you write, “The ongoing movement was forced into a hiatus as the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the city and its residents went into lockdown. To no one’s surprise, Beijing officials took advantage of this dormant period by heightening ‘security’ to chip away at the city’s pro-democracy camp. Increasingly aggressive actions towards pro-democracy lawmakers signaled what was to come. The Chinese communist party’s tolerance for the movement had reached a breaking point, and it was intent on further suppressing Hong Kong’s autonomy.”

There’s a lot of media blackouts right now, whether they are intended or unintended—even more than usual when there is no pandemic, when the United States media so often just ignores the rest of the world. How did the heightening of security by Hong Kong police forces and the Chinese communist party play out in the lives of those who were protesting prior to the pandemic? How did this affect their lives? We’re not getting reports of a clampdown on the pro-democracy movement during the pandemic.

I’m not using the word fascism lightly. It’s a politically repressive framework that has a history and is being revived and adopted in the Chinese academy and among Chinese elite police and intellectual circles—and it’s being directly deployed.

AW: The movement was forced into hiatus as the pandemic swept through the city. The national security laws were passed on June 30, and they contain the same clauses and rhetoric as proposals that were shelved back in 2003 when the Hong Kong government attempted to impose an anti-subversion law which criminalized “acts of treason, secession, sedition, and subversion” against the central government on the mainland.

Just over the past month, there have been new measures that criminalize broad forms of dissent. These laws have already targeted popular protest chants such as “Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times,” (you may have heard that one) as well as censoring school textbooks. It’s given the police force grounds to arrest protesters on virtually anything. Police brutality has been rampant since then. Even prior to the pandemic—we think back to July 21, the Yuen Long gang attacks, when the police allowed gang triads to beat up unarmed citizens on the metro. But into the pandemic, this rampant police brutality has built up over time. The police force has perpetuated violence using teargas, rubber bullets, even live rounds at times, as mentioned before, and even more recently we’ve seen restrictions on moving privileges. We’ve seen that there are business interests that control the electoral system as well.

PL: Andi covered a lot of amazing points, but I’ll just elaborate a little more on the national security laws. The key thing to know about them is that the final jurisdiction and interpretation of these laws are in the hands of the Beijing government. That effectively circumvents the “one country two systems” framework and overrides whatever was left of Hong Kong’s autonomy in the last year. I can’t really sugar coat it: the last month has been devastating for activists, and for everyday people. Within a month of the security law, there were tons of people arrested for not much of a reason—or they’re trying to find retroactive reasons to arrest protesters.

This was already happening before the national security laws, into the pandemic. It makes a lot of sense that the Chinese government is taking advantage of a lull in activism to arrest key leaders. In April and May it wasn’t that bad, but they were digging up charges for participating in a rally last August in order to arrest key movement leaders. This is completely heightened. With the national security laws, they have free rein.

The first person arrested under these laws was just holding a flag that said “Liberate Hong Kong.” People have been detained for holding stickers that just say “Conscience.” Ridiculous things like that. The judicial system is directly appointed by Beijing; now they have special security officers sent in by Beijing—all these things are being established while we speak. A founder of one of the pro-democracy papers was just arrested this morning, and the paper’s operations are being ransacked as we speak.

The Chinese government is also targeting diaspora activists in exile, and saying Chinese citizenship overrides whatever other citizenship you have. Samuel Chu, who’s based here in the United States, is a good example. He’s been doing a lot of activist work for the movement from abroad, and he’s been a US citizen for decades, and there’s now a warrant for his arrest despite the fact that he has dual citizenship.

In the wake of the pandemic and these national security laws, something little discussed in mainstream media is how the repressive framework behind these laws is neo-statist—that’s really the trendy word in Chinese academia. There are people who are literally drawing on jurists from the Nazi era. Carl Schmitt is an inspiration for people like Jiang Shigong, who has been at the center of Beijing’s policymaking apparatus towards Hong Kong.

This turn towards repression and policing cannot be divided from China’s and Hong Kong’s courting of Western capital—and capital in general. That really connects what’s going on in Hong Kong and China to other movements around the world: most notably what’s going on in Hungary with Viktor Orban and the resurgence of fascism. I’m not using the word fascism lightly. It’s a politically repressive framework that has a history and is being revived and adopted in the Chinese academy and among Chinese elite police and intellectual circles—and it’s being directly deployed. Hong Kong and Xinjiang are becoming experimental sites for the amping up of state violence.

CM: But Promise, according to the mainstream media, the original reason for these protests was simply an extradition bill that would extradite Hong Kongers to Beijing courts for crimes against the central government or the communist party in China. That extradition bill has been withdrawn. So why continue the protests if they achieved their goal? Or was the goal always more than just ending the extradition bill?

PL: The goal was definitely more than that. We’ve had five demands this whole time, and the end of the extradition bill was only part of that. Holding police accountable for violence and brutality is another one of the demands. But the main point here is that with the handover from the British government to the Chinese government, Hong Kongers’ civil liberties have not been guaranteed. In fact, the colonial apparatus has been completely maintained by the Chinese government.

I don’t like describing China as a “new” form of imperial actor or something. China and the Beijing government have been actively building off the anti-democratic mechanisms that the British put in place—things as basic as not having universal suffrage. That’s something that Hong Kongers don’t actually talk a lot about, but activists and leftists in the movement know about this limitation, this obstacle. In 1997, right before the handover, activists and politicians had fought for the right of workers to collective bargaining. That’s was hard fought, and it finally passed on the eve of the handover, and that was one of the very first things that the Beijing government abolished upon its rule.

Then there are pro-Beijing unions who are actively fighting against the reinstatement of workers’ rights and collective bargaining—which is just completely ridiculous as a trade union or any organization branding itself as the left. Hong Kongers, activists are uniquely attuned to these losses of civil liberties right off the bat, and the preservation of these losses. In the last twenty years, more and more civil liberties have been gradually lost, and more and more of the promises Beijing tries to guarantee its people are abolished and forgotten. There had been traditional opposition to Beijing rule, from the pan-democratic camp—and people have also lost faith in that. That’s why we see this resurgence of more militant strategies in the last year, just to fight for something so basic.

There is a chorus of voices from the Chinese civil society that is opposed to the turn to capital, the turn to policing, the turn to anti-democracy.

Key for people is the right to vote. There are “functional constituencies,” so-called, that control key parts of the state apparatus in Hong Kong, and those are directly controlled by business interests. Really the center of power is not in the hands of the Hong Kong people. That’s why in the district council elections—the unofficial primary was last month—there are people turning out en masse, hundreds of thousands of people voting in these elections that don’t really mean that much in the end, practically speaking. The primaries are unofficial, and as people all predicted, Beijing has banned almost all those candidates that were voted on in primaries. The district council isn’t even really a power-making body, and people were still trying to exercise power to show the international community that we just want something as basic as the right to vote.

Leftists on the ground are struggling to raise class demands and deeper systemic issues, which of course we view as tied to the question of universal suffrage and basic democracy. But in the face of repression and the narrowing of political possibilities, the right to vote ends up being a very important indicator of what Hong Kong people want moving forward.

So definitely, it’s more than just the anti-extradition bill.

CM: Andi, last week we talked to William Shoki, a writer at Africa is a Country, live from Johannesburg, South Africa. He mentioned the impact of US global cultural hegemony, and television programs out of the US that depict racialized policing and glamorize tough-on-crime, law-and-order policing, and the impact that has had on the culture of policing in South Africa. You point out the long standing exchange between US law enforcement and the Hong Kong police force:

“The Hong Kong police force has for years been a beneficiary of weapons and other riot control technologies from US firms, many of which are also used against Black protesters and their allies today in the US. With police abolition rapidly becoming a global clarion call, Hong Kong should serve as a concrete example of extending a campaign first begun in the US: preventing the spread and adoption of US-style policing and counterinsurgency methods by other countries.”

To what extent do you hold the US responsible for globalizing our problematic policing that includes racialized violence against people of color? Is the world’s policing problem that people are rising up against right now—is that all the United States’ fault?

AW: Thanks for that question. I think it should be our duty as leftists to oppose and stop the spread of US-style policing and imperialism. As leftists we also have a responsibility to hold accountable all enablers of this US imperialism abroad, especially the Chinese state.

CM: Promise, you write, “In effect now for only a few weeks, the laws have already banned popular protest chants, censored school textbooks, and have given the Hong Kong police force grounds to arrest protesters for raising blank placards in silence.” That’s the thing that really got me. You were mentioning waving a flag, but people are getting arrested just for holding a blank sign. “This crackdown on dissent reinforces the Chinese communist party’s determination to uphold its political power, which translates into the expansion of capital’s power.”

So Promise, is being anti-China being anti-communist or being anti-capitalist?

PL: China has blazed its very own unique path of what it means to do capitalist exploitation. But no, being against China is not being against the central principles of communism: basic radical democracy where workers own the means of production. Despite what Grayzone or tankie writers say, workers do not own the means of production in China. A lot of it is lip service, and workers are being massively exploited—at a rate that rivals a lot of Western countries—in China and in Hong Kong.

So yes, being against the operations of the Beijing government is being anti-capitalist and should be the duty of anti-capitalists worldwide. That still doesn’t translate into being “anti-China” in terms of being anti-Chinese people. That should not give cover for anti-Chinese racism that we see in mainstream US media, with the narrative of a “clash of civilizations” that Pompeo and even Biden are echoing now. Leftists should remain vigilant in resisting that type of anti-Chinese rehashed Yellow Peril xenophobia, and we should stand in solidarity with agents of reform. There are very complex elements going on in China, and there have been a lot of amazing activists and working class movements that are still waging the struggle, and we should stand in solidarity with those elements.

We must stand with people and not states, as leftists. There are a lot of complicated elements going on in China under the communist party. There are reform-oriented elements even within the party. There are Maoist-influenced new leftists who skirt the line: they don’t really get on the government’s bad side, but at the same time they try to make subtle critiques of the turn to market reform in China.

Whether you side with the anarchists in China or you side with the new leftists who are more sanctioned or recognized by he government, what we need to know is that there is a chorus of voices from the Chinese civil society that is opposed to the turn to capital, the turn to policing, the turn to anti-democracy. Of course I have my own political allegiances and ideological preferences, but the key is for people to start reading these critiques of the Chinese state and the direction it’s going in, and to think for yourselves as US leftists, and see what it means to articulate an anticapitalist practice from your positionality. That doesn’t entail defending or apologizing for the Chinese state.

CM: Andi, your question follows up on that. What happens to left politics when we determine what is legitimate or not based on Trump’s position on the policy? What happens when the left determines its positions on policies simply by asking what Trump or Fox News is doing and then standing on the opposite side? What happens to left politics when that’s the framing?

AW: It’s a good question. What we need is positive vision for left activism. If you’re viewing global protest events only from the lens of opposing what Trump is doing, you’re missing the whole picture. Like we mentioned before, we need to keep in mind that we can’t look at every movement from such a binary lens. We need to look at mass movements from global perspectives. Just because we see symbols from the US at a demonstration doesn’t mean we can refrain from commenting on what’s going on in Hong Kong. We need alternatives to Trump’s rhetoric. We all know that he doesn’t have the interests of the working class at heart. If the left doesn’t occupy that space and discourse, then the right will.

CM: Andi, Promise, I really enjoyed this conversation. Thank you both so much for being on the show.

PL: Thank you.

AW: Thanks for having us.