AntiNote: “This past year have we lost more comrades to fascist attacks or to suicide? Really wish I coulda gotten through life without ever posing such an ugly question, but our struggle has willfully absorbed these huge blindspots from society and some days I wanna say f.u. to half y’all.”

The above missive was posted online by a well-known anarchist revolutionary on 1 July 2021. The question of these blindspots has been weighing heavily on our writers collective lately as well. The world and our struggles have experienced such profound losses in recent days, weeks, months, years—always has, and yet with society attempting to “move on” from the decimations (still ongoing) of the COVID-19 pandemic, while also ignoring the pre-trauma of impending and continuing climate collapse, all amid the gaining hegemony of genocidal discourses worldwide…it’s rather astonishing how little attention our movements appear to be putting into processes of collective grief and solidarity.

Is it that hard to name? Aren’t we trying to fight the forces of death with life? A certain do-or-die, fight-like-there-is-no-future attitude has crept into a lot of our most vital spaces of resistance. There’s a nihilism in this that is concerning, and causes us to elide and devalue—even dismiss or disparage—the real pain and suffering and trauma being experienced by so many comrades, by literally all of us.

We are grateful to Scott Campbell for the following essay, which we interpret as an attempt to break the ice. Let’s keep talking about this together, even and especially because we aren’t supposed to.

Reprinted with kind permission of the author. The original post contains embedded videos we have not reproduced, check them out there.

Things We Aren’t Supposed to Talk About

by Scott Campbell for Falling into Incandescence

20 May 2021 (original post)

Content Warning: Includes discussion of self harm and suicide.

For T, J, T, R, and E

I have the annoying habit of smiling all the time. It’s a defense mechanism. It is meant to make someone like me, to appear friendly, amiable and amenable, and to wordlessly deflect any inquiry into my mood or state of being. It’s designed to pacify, to make one not worry about me. It began in childhood and is now reflexive. It takes conscious effort, active thought, and muscle manipulation to not smile. For decades I have heard about my “beautiful smile” and how “Scott is always smiling.”

As related to me by my parents, once I was able to crawl, when I had to cry, I would crawl into an empty room to do it, so as not to bother anyone. Though I can now walk, I still do that today. Smile all the way into the empty room, or car, or bathroom floor, until I can weep freely. Though even that’s not true: I try to avoid making too much noise so as not to attract attention.

Fact is, after four decades, I’m still trying to figure out how to have feelings in a world that, as least as far as I’ve been instructed by it, tells me they’re not welcome. So I smile, say, “I’m good, thanks,” and close the door to sob and heave tears and mucous and muffled cries into a pillow. Worse is when feelings emerge out of nowhere and one has to stifle them with all one’s effort while still appearing normal, or turn off one’s camera on Zoom until one composes oneself and extinguishes all evidence of unwellness.

I’ve been anxious ever since I can remember and depressed since I was I teenager. Since then, I’ve pursued a dual course of treatment. On the one hand, seeing innumerable therapists, psychologists, psychiatrists, emptying a pharmacy’s worth of psych meds, and trying out plenty of “alternative” treatments. On the other hand, I’ve followed a similar regimen of self-treatment involving a variety of substances not approved by the FDA, along with self-harm and suicide attempts. All that just got me back into the hands of psych wards, rehabs, more therapists and medications. Neither course of action has worked.

For the past few months, I’ve been in one of the worst depressive episodes in years. At the moment, I’m on three psych meds, in therapy, and getting my head pummeled daily by magnetic coils, and things only seem to be getting worse. As a lethargic, embodied specter of my former self, a being filled with only searing emptiness, I’ve been contemplating many things. One is how I shouldn’t be talking about this. How we are told, managed, encouraged, warned, chided, shunned into not talking about this. So I want to talk about it. Because I don’t know what else to do.

In “mental health” (the Cartesian curse continues), I find many resonances of Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, in which he argues that counter to prevailing common sense, we do not live in an era of sexual repression but rather one in which sex has been rendered into a discourse of sexuality, where sexuality and the knowledge-power of it is used as a means to discipline, control, and surveil via a variety of state and non-state institutions at the individual and population-wide levels. Ultimately, this culminates into his theory of biopower – of disciplining the individual body and determining who lives and who dies at the macro level.

Foucault may make this very argument in Madness and Civilization, which I have not read, but it seems to me that “mental health” and “mental illness” are similarly discursive technologies of power akin to sexuality. “Mental health” is discussed everywhere, so much so that we appear to be a society accepting of it. Yet at the same time, it is obfuscated, hidden away, regulated, and surveilled according to legal and societal norms. One is not allowed to be mad-at-large in this society. One can only be mad by oneself, or during the span of forty-five minutes with a state-authorized therapist, or while “objectively” describing one’s madness to a state-authorized psychiatrist who can only administer dubiously effective state-authorized medication. One cannot be mad at work, out in the streets, in school. The mad one needs to be removed from these settings to go “get well” on their own. One who is mad must watch what they say about their own madness or risk involuntary incarceration by the state.

Effectively our madness is monitored, legislated, carceral, and permitted only in certain settings, as if it is something we can turn off and on at will, rather than that which it is, that which eats at you during every second of consciousness, which grinds you into dust, stomps on your soul, and renders you merely a husk of a human. Madness is measured according to DSMs, diagnosis codes, BDI assessments, and insurance pre-authorizations, as if our pain can ever be encapsulated by words or ranked on a numeric scale. Our society and its norms want us to be mad at its convenience and within its ambit. If we violate their norms, we will be forcibly removed from society – incarcerated in its prisons or its prisons psychiatric institutions (see Decarcerating Disability). Madness as individual deviance, with no reflection on why so many of us are so goddamn mad in this world. So instead of being real, we smile and say we’re “fine, thanks, and how are you?”

From a personal angle, severe depression effectively changes the way I see the world. By this I do not mean the fact that depression crushes one’s interest in everything, colors all through a lens hued by ennui and melancholia, makes molehills or even smooth, downward slopes into mountains impossible to set foot on, let alone summit. Rather, my experience of quotidian objects in the world changes. In grad school, I had to read Being and Time by everyone’s favorite Nazi phenomenological ontologist, Martin Heidegger. All I recall of the text was a seemingly interminable (but likely only five pages) investigation into what makes a hammer a hammer and not something else. For Heidegger, a “hammer-Thing” is a “hammer-Thing” because it is the best possible “Thing” for hammering. And so it goes with other objects. Our phenomenological creation and use encounters with them render them into what they are.

Yet depression, especially one accompanied by suicidal ideations, fantasies, and planning, phenomenologically changes how I see objects. A car is not a car, but a heavy, fast machine to drive into a tree. A bathtub is not a bathtub, but a one-person abattoir. A staircase railing is not a staircase railing but a gallows. It is severely disconcerting to encounter seemingly banal objects and have their – ultimately ontological – Being-in-itself drastically change. And to force oneself to remember what they actually phenomenologically are.

If I may venture into more morbid territory, nothing exemplifies this experience for me better than the knife. Like many people in the midst of severe depression, I harm myself. It’s something I’ve done since I was sixteen. We always carry the deeper hurt on the inside, but a glimpse at the flesh’s latticework of wounds can convey its own story. For me, the knife becomes a plea, a prayer, and a gamble. A plea for release from the pain, a prayer for a breath of respite between this life of ache and the permanence of death, and a gamble that this next cut might be the last. There is ambivalence about the outcome, as I truly don’t want to die, but this current experience makes going Home and finally being at rest irresistibly tempting.

It may seem odd, but I often wonder why I truly don’t want to die. Certainly, there is the instinctual drive for self-preservation (with a noted counterpoint to Freud and Thanatos.) There is also the cognitive awareness that this episode will eventually pass. Though the adage that suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem doesn’t hold much water for me, as this “temporary” has now spanned decades. Experience guarantees what passes will again return. Perhaps there is the hope that, despite all evidence to the contrary, maybe things can get better, maybe the haunting shadow will dissipate, or be integrated, or just piss off. But maybe there is something else, something about the very nature of depression in our current era.

Throughout this period, I have been re-watching the television series Rectify. Which is not a wise viewing selection while depressed but is one of the best shows I’ve seen, both in general and as an argument for abolition. Throughout the four seasons, a line is repeated several times that always gives me chills: “It’s the beauty, not the ugly, that hurts the most.” While my demons (and daemons) are personal, I believe many are also collective. And we live in a very ugly world. That hurts. That hurts so much it is maddening. At the same time, this world is beautiful. It is so awesomely beautiful. Life, Earth, this universe is incredulously beautiful. And that hurts. That hurts because we are so much more than this ugliness which reigns. That hurts because despite the ugly, and its armies, and cops, and nation-states, and economic systems, and institutional violence, there is so much beauty.

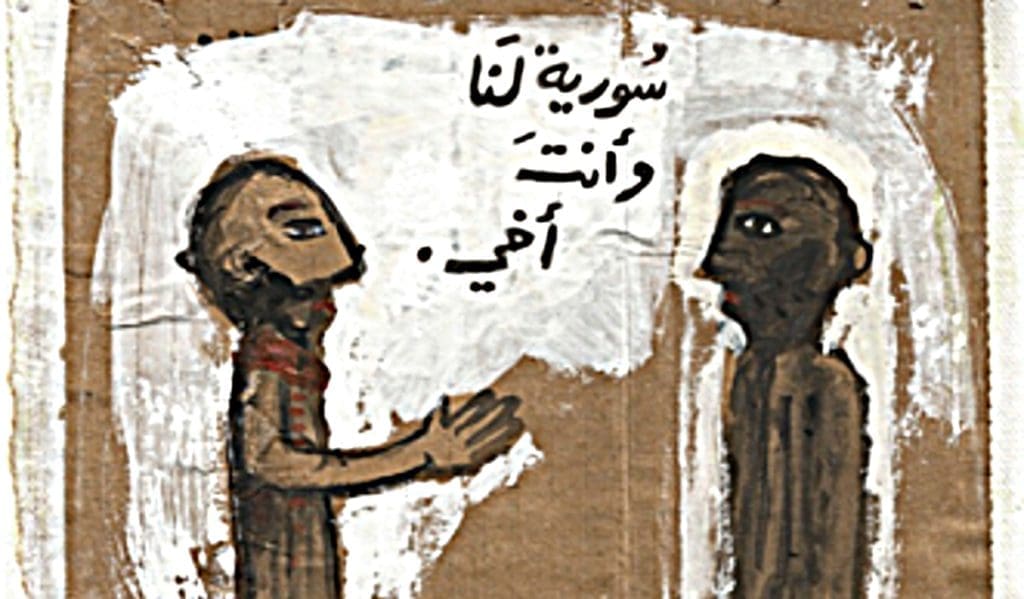

There is beauty right now in Palestine, Colombia, Myanmar. There is beauty in the resistance, the art, the songs, the creativity, and the resilience. There is beauty in the hugs from my parents, the love of my friends, the support from my teachers. That all hurts the most, more than the ugly, because it points to what we are capable of, what potential we have, what dreams and cosmic prayers remain on hold yet await actualization. That we’re made of stars, and we can shine just as brightly, but rarely do we get the chance. Too often we are extinguished. But there is that beauty, that painful brilliance, in each of us, and it cannot be shackled forever. As one of my favorite poets, Amir Sulaiman, says, “The human being, god…only if the human beings knew who the human beings are, my lord.” I think I hurt from the ugly and that’s only amplified by the ache of the beauty, an ache all the stronger as it fends for survival amidst the ugly.

So maybe I stick around less out of instinct and more to feel and fight and hopefully add to the beauty. I just hope that’s enough. Even scars can be beautiful.

[Disclaimer: I wrote the above to try to help me make sense of my current moment. It is not a call for help or plea for attention. I’m not seeking rescuing, intervention, or even consoling or sympathetic comments. I just wanted to be real, to talk about what we’re told not to talk about, and to let others in similar situations know I see you and feel you. Thank you for reading.]