Absolutely Horizontal

How autonomous humanitarian networks channel strangers to safety

translated by the Russian Reader from The Village (original post in Russian)

9 May 2022 (original post in English)

Olga lived in Mariupol for many years. Until February 24, she worked as a courier while her husband worked at the Azovstal steel works and their two children studied at school. Since early March 2022, due to the so-called special operation, Mariupol has been under siege, and fighting has been going on in the city. In the middle of the month, when humanitarian corridors opened up, the family was able to get to Donetsk, and from there they took a bus to Petersburg. Their bus tickets were bought by volunteers—ordinary people who are not connected with government agencies. Volunteers also met the Mariupol residents in Petersburg and housed them in their apartment for the night, and then took them to Ivangorod, where Olga and her relatives crossed the Estonian border. The family is now in Finland.

There are many similar stories. In Petersburg, hundreds of residents help transit refugees every day. There are so many people willing to help that all requests—from putting up a family of five people and two dogs to transporting a nursing mother with a baby to Ivangorod—are claimed by volunteers in a matter of minutes. Over the border, in the Estonian city of Narva, Ukrainians are also welcomed by volunteers. This is the story of how ordinary citizens sat and watched the news, feeling powerless, but then found an opportunity to help others and themselves.

How Volunteering Heals Witness Trauma

Alexander from Petersburg is an artist. If it weren’t for [the war], he would now be engaged in art making. “I won’t be getting around to art anytime soon, but there will be food for it,” he says.

In April, Alexander and other volunteers launched a platform on the internet where they coordinate requests for assistance in crossing the border with Estonia and (less often) Finland. For security reasons and at the request of the volunteers, we are not publishing a link to this resource. Currently, there are more people willing to help than requests for help: people snap up the requests in minutes.

Here is an example of a typical request: “A family is coming from Mariupol: a grandmother, grandfather, their daughter, grandson (twelve years old), and a pregnant cat. You need to meet them at the train station, feed them, provide overnight accommodation, chip the cat and put the family on the bus to Tallinn the next morning.”

“Society has been traumatized,” says Alexander. “People were watching the news and tortured by a feeling of impotence, so we created a platform where we try to cure this powerlessness. I have the feeling that any problem can be solved en masse. People are competing for the opportunity to help, and so [the campaign] has turned out absolutely horizontal. People find the requests on their own and fulfill them on their own. In the past, I worked on the problems in my neighborhood, and back then it was several activists dragging the whole movement like locomotives, but now the wave rolls on by itself.”

We thought we were going to disappear inside Russia, the refugees tell local volunteers. People travel mostly in groups. Most of them are women, children, and the elderly. There are fewer men. “Many people are traveling with their pets,” says Alexander. In addition to Mariupol and the surrounding area, they come from the Kharkiv region, Donetsk, and Luhansk. They are going to European countries, but some seek to return to Ukraine as quickly as possible because they have relatives there, they can speak their native language, and they don’t have to deal with the “refugee” label.

It is not only Petersburgers who have been helping them to make the journey to the Russian-Estonian border. There are also hundreds of volunteers in Moscow. The Petersburgers are now establishing contacts in Rostov, Krasnodar, and Belgorod, the [southern] Russian cities through which the refugees travel most often.

“The other day I came to my senses, looked up from the screen, and realized that nothing was hurting inside me. I haven’t watched the news for more than a week and I don’t know what is happening in the political space. I have a specific task, it is very simple and clean. Unlike everything else, I have no doubt that it’s a good thing,” says Alexander. “Everyone wants to do good, and helping refugees certainly satisfies this need.”

How Natalia Got from Mariupol to Vilnius via Petersburg

Natalia got from Ukraine to Lithuania thanks to the internet platform where Alexander volunteers.

Previously, she worked as a cook in the Shchiriy Kum retail chain. She has two daughters: one is a high school student, the other, a university student. On the morning of February 24, Natalia went to work as usual. “I heard that there had been an explosion somewhere. But in Mariupol this is so routine that no one paid it any mind” (echoes of fighting have been audible in Mariupol since 2014, and most residents were used to the sounds of distant explosions and shooting —The Village). “When I arrived at work, I realized that things were serious. I finished up by three o’clock, and they let us go home. I didn’t go to work anymore after that.”

Natalia and her family remained in Mariupol until March 23. There was no “serious fighting” in her neighborhood, so she and her daughters stayed in their apartment, not in a basement or a bomb shelter. “But our things were packed to leave at any moment,” she says. The electricity in the city had been turned off, and the water was also turned off, so the family went to a spring to get water. Then the gas was turned off, so they had to cook on a bonfire.

When the fighting got close, Natalia, her girls, and her eldest daughter’s boyfriend went to the outskirts of city, where “there were buses from the [Donetsk People’s Republic].” They went on one of these buses to her parents who live near Mariupol and stayed there for three weeks. Then all four of them traveled to Taganrog [a Russian city approximately 120km east of Mariupol]. At the local temporary accommodation point, they were offered a choice: they could go either to Khabarovsk or to Perm. Natalia didn’t want to go to Khabarovsk or Perm. She needed to get to Lithuania, where a friend of hers lives. That was when a Mariupol acquaintance put her in touch with the Petersburg volunteers.

“The volunteers bought us tickets to Petersburg. We got to Rostov, where we boarded a train. In Petersburg, we were met by Ivan, who took us home to eat. We washed up and changed clothes, and he took us to get on a minibus to Ivangorod,” Natalia says. The Mariupol residents crossed the Russian-Estonian border on April 23. “At the Russian border, they asked [my daughter’s boyfriend] where he was going and why.” The Petersburg volunteers had put Natalia in touch with Narva volunteers, and so the family immediately boarded a free bus to Riga.

Natalia is currently in Vilnius. She has no plans to leave—she no longer has the strength to travel with suitcases. “We’ve rented a room. We’re going to look for jobs,” she says.

How to Help via Twitter

“It all started with the fact that I felt helpless and useless. I really wanted to do something,” says Katya from Petersburg.

You can find out about helping refugees who are traveling to Europe via Petersburg on various websites. The one on which the artist Alexander volunteers is the largest. There are others. For example, Katya saw such a request on Twitter. In mid-April, a friend of hers asked whether anyone could welcome a family (a mother, son, and daughter) and an eighteen-year-old girl who was traveling with them for a couple of days. Katya responded. The family was put up by her friend, while Katya took in the girl. “She met the family she came with two weeks before [the war]. They went for a walk once with the boy, and he decided to take her with him. Her mother refused to leave, and so now the girl is all alone, without relatives here,” says Katya.

Katya met the girl at the Moscow railway station and they traveled the rest of the way to her house. The question arose: how to talk to a person whose country has been invaded by your own country? “Either we were a match, or the girl herself is this way, but it was easy to communicate with her, like with a sister,” says Katya. They sat down to drink tea, and the girl recounted in a calm voice how one day a tank drove up to the nine-story building in Mariupol where she was hiding in a bomb shelter, raised its turret, and began shooting into the distance. “I was bored, and I started counting. It fired seventy shots,” the girl said.

Before the girl left, Katya and her guest hugged tightly. The Mariupol family eventually stayed in Sweden, while the girl ended up in Germany. “I was constantly thinking about what is it like to live when your city is gone, when it has been wiped off the face of the earth,” says Katya.

What Ivangorod, the Transit Point for Refugees Going to Estonia, Looks Like

It takes two hours to drive from Petersburg to Ivangorod. At the outskirts of the city, you need to show the frontier guards a passport or a special pass for entering the border zone. Refugees are allowed through with an internal Ukrainian passport. A kilometer from the checkpoint, on a pole right next to the highway, storks have built a large nest.

Ivangorod is home to around nine thousand people. Its main attraction is a medieval fortress. In the six years that have passed since The Village’s correspondents last visited the city, it has become prettier. The local public spaces have been beautified under the federal government’s Comfortable Environment program.

Estonia can be seen from the bank of the Narva River. To get to the European Union, you need to walk 162 meters across the Friendship Bridge. At the entrance there is a hut where insurance used to be sold, but now it is abandoned, its windows broken. People walk down the slope carrying bags and plastic sacks stuffed with things. The local children ride scooters. Closer to the shore, the children turn right onto the embankment, which the local authorities attempted to beautify in the 2010s with funding from the EU. The people carrying bags go to the left.

There are several dozen people at the border checkpoint. A heart-rending meow resounds from the middle of the queue. A woman removes a black jacket from a pet carrier: a hairless Sphinx cat stares at her indignantly.

“Maybe I should let him out on the grass?”

The people in the queue say there is no need, that they will get through quickly. But it seems that this forecast is too optimistic.

“Are they all Ukrainians?” a man with a reflector asks loudly. The people in front of him shrug their shoulders. “Are they Maidanovites? Refugees? Are they fleeing from the nationalists?”

Someone argues that the frontier guards should organize two queues—“for people and for refugees”—to make the border crossing go more quickly.

Under the bar at the border restaurant Vityaz hangs a homemade “Peace! Labor! May!” banner and an image of a dove. On the way to the Ivangorod fortress there is a memorial stone dedicated to “the militiamen, volunteers, and civilians who perished and suffered in the crucible of the war in the Donbas.” The Village‘s correspondents did not encounter a single letter Z—the symbol of the “special operation”—in Ivangorod. Nor they did encounter a single pacifist message either.

How Narva Helps Transit Refugees

At the border checkpoint, people are met by numerous volunteers from various associations, including the Friends of Mariupol. “These are all private initiatives,” says Narva volunteer Marina Koreshkova.

“We have been seeing exhausted people,” says Marina. “Many are in rough psychological condition, and they really want to talk. We listen to them for an hour, two, three—we empathize with them and share important information. People say that while they were traveling through Russia, they saw the Z, heard unpleasant messages addressed to Ukrainians, and were forced to put up with it and remain silent just to get to Europe. But I often see examples of Stockholm syndrome. Or maybe people are just afraid to say the wrong thing.”

Six years ago, Marina and her children moved to Narva from Petersburg, because she understood that the situation in Russia was getting worse. In Russia, she was a lawyer, working for ten years in a government committee on social policy, then as an arbitration manager. She started her life from scratch in Narva, and is now studying new professions. She is a member of Art Republic Krenholmia and Narva Meediaklubi, nonprofits engaged in civil society development and social and creative projects.

On April 10, Marina received a call from the manager of the Vaba Lava Theater Center, who said that they had decided to temporarily convert a hostel for actors into an overnight accommodation for refugees. Soon, the Narva Art Residence also let transit refugees into its hostel for artists. Then the Ingria House, located near the train station, equipped a room to accommodate Ukrainians. And on May 1, a Narva businessman temporarily vacated his office, located near the border, for daytime stays.

“For the first week, Sergei [Tsvetkov, another volunteer] and I tried to do everything ourselves. We quickly realized that at this pace we would burn out or get sick. Now about sixty local volunteers are involved, and people have come from Tallinn to help. The number of people helping out has been growing every day. Local residents collect the refugees’ laundry for washing, and bring them food and medicine.”

Almost none of the refugees remain in Narva. “The proximity to the border generates a new sense of uncertainty for them,” Marina argues. In addition, the region’s refugee registration office, which enables Ukrainians to gain a foothold in Estonia, has been closed. The nearest one still in operation is in Tartu [a distance of 180km from Narva by car].

Narva is also “the most Russian city in NATO.” Only four percent of the city’s population is ethnic Estonian, and thirty-six percent of residents hold a Russian passport. “I don’t have time to read social media, but until April 10, I constantly observed negative comments [from Narva residents] about the refugees, although I have not seen any outward aggression in the city,” says Marina.

She believes that a welcoming station where refugees could get basic information and relax inside in the warmth should be equipped at the border. “It was quite cold in late April. People were freezing on the border outside in the wind, then thawing out for an hour and not taking off their outerwear.”

There is not even a toilet on the Russian side of the border, however.

Source: “‘An absolutely horizontal business’: How residents of Petersburg and Narva are helping Ukrainian refugees going to Europe,” The Village, 5 May 2022. Thanks to JG for the story and the link. Translated by the Russian Reader

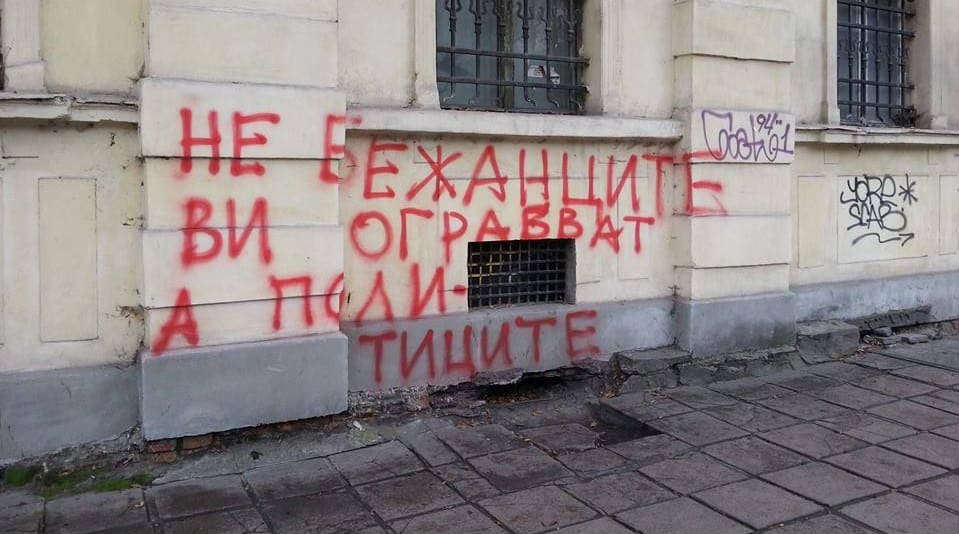

Featured image source: The Village via the Russian Reader