AntiNote: This interview was published in Czech by the Prague-based webzine Alarm. Presented here is an automated translation into English, lightly edited by a non-Czech-speaking human. Posted with the kind permission of both parties to the conversation.

“I hope the Russian empire will be destroyed!”

Interview with Robin Yassin-Kassab by Bohumir Krampera for Alarm (Czech Republic)

10 August 2022 (original post in Czech)

Syrian-British journalist Robin Yassin-Kassab on the connections between the wars in Syria and Ukraine, the failure of the Western left, and ways to deepen democratic institutions.

Note from Alarm: Robin Yassin-Kassab is a Syrian-British journalist and writer. Born in London in 1969, he has lived and worked in Great Britain, France, Pakistan, Turkey, Syria, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Oman. He is author of the novel The Road from Damascus and co-author of the influential book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, which was shortlisted for the prestigious Folio Prize in 2017. Yassin-Kassab was co-editor of Critical Muslim magazine and currently contributes to the online magazine PULSE, which was named one of the top five journalism sites by Le Monde Diplomatique. His articles on Syria have appeared in The Guardian, The National, Foreign Policy, Daily Beast, Newsweek and Al Jazeera.

Currently, Yassin-Kassab lives in Britain, writes short prose, and comments—together with his wife Leila al-Shami—on the situation not only in Syria and the Middle East, but also in Ukraine. Al-Shami’s text “Anti-imperialism of idiots” became a basic point of reference for the discussion of the so-called anti-imperialist left in the West and was referred to several times by the democratic and anti-authoritarian left in Eastern Europe in connection with Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Bohumir Krampera: What are the biggest differences or parallels you see between the situation in Ukraine and the situation in Syria? What were your first thoughts when you heard that Russia had invaded Ukraine?

Robin Yassin-Kassab: For Syrians and people connected to Syria, the situation in Ukraine is very traumatic. It brings back unpleasant memories of when Russia got involved in the war in Syria. Many people are shocked to see Russia bombing civilians, hospitals, schools, and other civilian targets. It did not surprise us Syrians; it is a Russian war method. Civilians are harmed in all wars, but in Russia’s case civilians are often the main target. In Syria, their strategy was to destroy the civilian base of the Syrian revolution, to destroy the people on whom democracy could stand—those who organized themselves on a democratic basis. In Syria, Russia destroyed hospitals and other civilian targets such as bakeries, schools, residential areas. They bombed them repeatedly until they were completely destroyed. Their goal was to drive the local population away. Millions of people fled to neighboring countries.

BK: You talked about the democratic revolution in Syria, but this is not a common perspective. Most people talk about jihadists and terrorists in relation to the Syrian revolution. You personally were in contact with representatives of the democratic opposition in Syria. Now Russia is trying something similar, talking about Nazis in Ukraine—but this myth is not yet as widely accepted as the myth about Syrian terrorists. Why do you think that is?

RY: At the time when Russian troops arrived in Syria, there were jihadist groups in the country—though there was a difference between Syrian Islamist groups whose goal was to overthrow Bashar al-Assad and establish an Islamic-centered system in Syria, and international jihadist groups who took advantage of the country’s chaos. The latter came from abroad and took advantage of the political vacuum—I mean groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. These groups were already present when the Russians came. Local jihadists, on the other hand, were created by Assad’s war against the Syrian people. When the revolution started in 2011, almost no one was at that point. The vast majority of people protested and risked their lives at demonstrations without any weapons. We’re talking about millions of people. It also involved all nationalities and religious segments of Syrian society. They all protested for human rights, democracy.

Russia’s military defeat in Ukraine and its subsequent collapse would be good news not only for people in Europe, but also in the Middle East and the Sahel. It would open greater free space not only in these areas, but also in Russia itself. I hope for the defeat of Russia and I hope that it will be overwhelming.

To understand the evolution of the revolution in Syria, it is important to focus on the way the Assad regime supported the Islamic and jihadist opposition. Islamists existed in Syrian society—look at the situation in the country in the eighties—but they were not very influential in 2011 and 2012. It was only the way the regime reacted to demonstrations and protest movements that turned them into a relevant component of the opposition. I’m referring to extreme violence that had a strong traumatizing effect. Many ordinary people began to cling to religion. It’s a natural reaction. When you see your relatives and friends die, you start thinking more about god and the afterlife, especially in a society that is religious. While the regime arrested several tens of thousands of often young, secular, and democratically minded people, at the same time it also released roughly 1,500 Islamists and jihadists from prisons. Among these people were, for example, Zahran Alloush (commander of Jaysh al-Islam) or Hassan Aboud, who founded the group Ahrar al-Sham. Releasing Islamists and jihadists from prison while democrats and secularists were being arrested and murdered was a deliberate tactic by the Assad regime.

BK: The Syrian revolution has never had much support from Western politicians, intellectuals, or activists. The West has never given the kind of support to the democratic opposition in Syria that it is now giving to the Ukrainian people in their fight against Russian aggression. Now, we are not so strict and do not evaluate whether some parts of Ukrainian society are more nationalistic. Why was it different in the case of Syria?

RY: In my opinion, a mixture of ignorance, racism, Islamophobia, and the failure of opposition politicians in the West was to blame. People think they know quite a lot about Syria and the Middle East, but they really don’t. They apply the knowledge they have from Iraq or Palestine, for example, to Syria. It is one “Arab World” for them, they are all “Muslims.” They think if they know one thing about Arabs or Muslims, they can transfer it to the entire Islamic world. This is as absurd as me thinking that I can apply my knowledge of Scottish politics to politics in Belarus or Texas. There was a belief that there was no need to ask Syrians about their experiences and opinions, because we already know how it is: If Iraq was thrown into chaos because of the American invasion, then surely the problems in Syria must be the result of American or Western interference in Syrian affairs. We in the West also know that there are jihadist groups operating in the Middle East, so when the president of Syria says he is fighting jihadists, we simply believe him. This is a grotesque simplification.

BK: What did you mean by the failure of the political opposition in the West?

RY: I’ve criticized the left a lot and some people think it’s because I’m on the right. I’m definitely not a rightwinger—I would describe myself more as an anarchist and a liberal. Democracy is an essential thing for me. We should look for ways to strengthen, deepen, and radicalize democracy. I don’t think we should throw dirt on liberal democracy, or on people who live under dictatorial regimes and desire such democracy. Democracy is in danger everywhere and we should do everything to defend it. I think the left has stopped trusting people. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the left still believed that mass popular movements could achieve larger and more radical democracies. Over the course of the century, however, the left lost faith in people and their ability to develop and radicalize democracy. It began to look at the world through the lens of a kind of “state game.”

It is a very simplistic, binary view of the world in which you have powers like the United States on one side and states like Russia, Iran, India, or Brazil on the other. Some representatives of the left began to think that we had to support, say, the Soviet Union against the United States in order to achieve some kind of geopolitical balance, that there is a need to support “anti-imperialist” Iran against “imperialist” states like the United States and Israel. This binary view of the world is of course ridiculous and does nothing to help the people in those countries. It does not help people in Russia or Iran. Such a view completely ignores the fact that Iran can be a victim of Western imperialism and at the same time be itself an imperialist in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, or Yemen. This view does not solve the problem of imperialism at all. It does not take into account that all states try to extend their influence over their neighbors or weaker states. In this way, we only see the problem from the perspective of the states, which overlooks the views of the people fighting for freedom within these states themselves.

BK: In the Czech Republic, there was a recent debate on social media about whether the left or the right is a greater ally of Putin’s Russia. Do you have an answer for this?

RY: They are all allies of Putin’s Russia. Left, right, and center. Russia is the global seat of the extreme right: Duginism, contemporary fascism, Christian radicalism.

BK: In this context, isn’t it a bit ridiculous that the Azov battalion is so often talked about in connection with Ukraine? The extreme right all over the world receives money from Russia.

RY: Yes, Russia is literally feeding the global extreme right. Everyone from Orbán to Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson to openly neo-Nazi groups often receive direct support from Russia. Russia doesn’t even hide it. It is absurd to focus on Azov and ignore the obvious fascism coming from Moscow. But I would still like to return to the left.

BK: You mentioned you criticize the left more than the right. Why, though? You said you don’t consider yourself a rightwinger.

RY: If the Syrians expected any support from the West in 2011, they certainly didn’t expect it from the right, but from the left. The nationalist or liberal capitalist right does not even pretend to support progressive or revolutionary movements. It is inherently against these movements. Either they don’t suit their financial interests, or they disrupt the given hierarchy. But we expected support from liberals and the left. We expected them to support a revolution that was organized from below, aimed at democracy and a fairer system, against a fascist and neoliberal regime. We almost took it for granted that people like Noam Chomsky, the British Labour party, or the left wing of the US Democratic party would support us. It was probably our ignorance, but the exact opposite happened.

BK: Is this a longer-term trend, or was it something that arose only from the events in Syria?

RY: This problem was there long before 2011. A whole range of leftists supported Milošević in Yugoslavia because they thought in terms of states’ intentions: The US is fighting on one side, so we have to support the other. Of course, this approach did not change the fact that a genocide of Muslims was taking place in the former Yugoslavia. Chomsky himself denied the genocide in Cambodia during Khmer Rouge rule. I believe that Chomsky should have been called upon in the 1970s to admit that he was wrong about Cambodia. Likewise, in the case of Bosnia, the left should have clearly rejected those who came with positions supporting Milošević. The left should have clearly rejected disinformation and genocide denial. If we had done this then, perhaps during the Arab Spring we would have been more supportive of democratic tendencies and clearly rejected those who see the world only as a battle of states.

This applies not only to the present—many leftists romanticize the crimes of authoritarians from the past as well. We have people proudly marching around the university saying, “I’m a Maoist,” or “I’m a Leninist” or “Trotskyist,” because they think it’s cool. We should have a serious discussion about this. Mao was responsible for the murder of tens of millions of people. Ignoring it because we like part of his ideology is an appalling form of racism, ignoring the suffering of the local people. The left went astray in the past because it was authoritarian, because it did not reject authoritarianism, and because it thought that democracy was not that important. They thought a small group of people could lead a country and make decisions for others. “All power to the Soviets!” but all power was taken from the Soviets and usurped by a small group in the leadership of the Communist party.

All this led to the enslavement of workers, to genocides, and finally to collapse in the 1990s. Well, now we can see where it led, and we are feeling the consequences today when we have a fascist version of Russian authoritarianism. If the left wants to be relevant again, it needs to realize that this was all wrong. We must create a broad consensus on anti-authoritarianism and recognize that the democracy we have, for example, in Scotland or the Czech Republic must not be a luxury for the middle and upper classes of the population, but must be preserved, deepened, and extended to others as well.

BK: In connection with the war in Syria, Jeremy Corbyn also holds very controversial positions. How do you view him?

RY: In 2014, Corbyn, in relation to the occupation of Crimea, used a number of arguments that we hear from the Kremlin today as the main reasons for invading Ukraine. When FSB agents poisoned Skripal, the British police came to the conclusion that the Russians were responsible and that they poisoned him with Novichok. According to Corbyn, however, it was not so clear.

Emily Thornberry, who was Corbyn’s shadow foreign secretary, raised the issue of the White Helmets in the British parliament. She demanded that no money go to the White Helmets from Great Britain, because they were said to be directly connected to al-Qaeda. Emily Thornberry is still in the leadership of the Labour party even under Keir Starmer. Thornberry now claims that she is against Putin, but a few months ago she was spreading Russian propaganda about Syria in the British parliament, in the case of the White Helmets.

Corbyn is one of the leading figures in the Stop the War Coalition, an organization that immediately organized demonstrations whenever the West symbolically bombed an empty Assad warehouse. But they never commented on the violence perpetrated by Assad, Iran, or the Russians in Syria. Now Corbyn promotes the theory, which is common among the Western left, that Russia was essentially provoked by Ukraine threatening to join NATO. In practice, this means that we will condemn Russian aggression, but in the same breath we will add that it is much more important to oppose the further expansion of NATO.

That is an argument I cannot agree with. Quite abstractly, I can agree with the idea that we should not support any military alliances made up of states and that we should try to create a world where such alliances do not exist. But the reality is that countries that were colonized by Russia in the past no longer want to be colonized by Russia, and that’s why they have joined or tried to join NATO. It must be acknowledged that they have good reasons. The Americans did not force them to take this step. These countries were afraid that Russia would want to colonize them again, and now we see this fear was justified. If Ukraine had had the opportunity to join NATO, its cities would not be under Russian fire today. At the time, NATO rejected it because it didn’t want to upset Russia. That is why today we see a change in Finland and Sweden, which want to join NATO in response to Russian aggression.

In that respect, I’m really glad Corbyn isn’t in power now. It is paradoxical because in theory we should be on the same side, but we are not. He claims to support Palestine. I am also for Palestine, against the Israeli state and its apartheid, and I support the rights of Palestinians. But the way in which Corbyn expresses his support for Palestine often verges on antisemitism, in my opinion. Corbyn, in an interview for Iranian television in 2012, said he sees an “Israeli footprint” in the terrorist attack in Egypt because it is in Israel’s interest to destabilize Egypt. But there was no evidence of Israeli involvement. You are not helping the Palestinians by claiming without evidence that Israel is behind terrorist attacks in Egypt. It’s just ignorance, and an inability to understand that the world is much more complicated and that bad things can happen in Egypt without Israel being involved.

When asked about one of Assad’s chemical attacks in Douma, Corbyn said, “You know, we have to be very careful and watch what the Saudis do with British weapons.” What did he mean by that? That the Saudis committed the chemical attack in Syria? Or was he implying that what the Saudis are doing in Yemen is worse than what Assad is doing in Syria, and therefore we should not talk about the crimes in Syria?

This is exactly how Russian propaganda and disinformation works. Various half-truths are spewed out. Some will be taken by the right, others by the left. Thus confusion sets in, in which no one is sure of what’s really going on. Suddenly, there are so many options that it’s impossible to have a clear opinion and make judgments. People are unable to hold positions or take action in any way. It’s a terribly dangerous kind of politics, and it’s definitely not leftwing. It doesn’t help anyone, neither the oppressed nor the poor. It doesn’t help the Palestinians, it doesn’t help the Syrians, nor the Ukrainians. It only makes the left less and less relevant, but more dangerous. A lot of young progressives, when they see Corbyn and the current political representation, say, “He’s against racism, he’s against war,” and they support him. But in reality, his politics are based on conspiracy theories, a meaningless binary view of the world, and authoritarianism.

BK: You are a Syrian, an activist, and a person who is in contact with the opposition and democratically minded people in Syria. How do these people view the war in Ukraine?

RY: Most of them are interested in Ukraine. They feel they have the same enemy. But at this point it is important to say that the Syrian revolution has been crushed. It doesn’t mean it was defeated forever, it may come back in a different form, but it really was defeated, and Russia is to blame. It is also necessary to state that not all Syrians are or were against the regime. There is a part of the population that supports the regime and thus also supports Russia, because the regime has survived only thanks to Russia. The Syrian regime would have no power if it weren’t for Russian imperialism fueling it.

That is why we are seeing some loyalist Syrians going to fight for Russia in Ukraine. We see the same thing in Libya, where fighters are leaving the territories controlled by Khalifa Haftar for Ukraine. I don’t know what real military impact this might have, but it’s like a scene out of the nineteenth century. It’s classic imperialism. The French did it—when they pacified the rebellion in Syria in the 1920s, they called in troops from Senegal and Morocco. The British did the same. It’s just typical imperialist behavior.

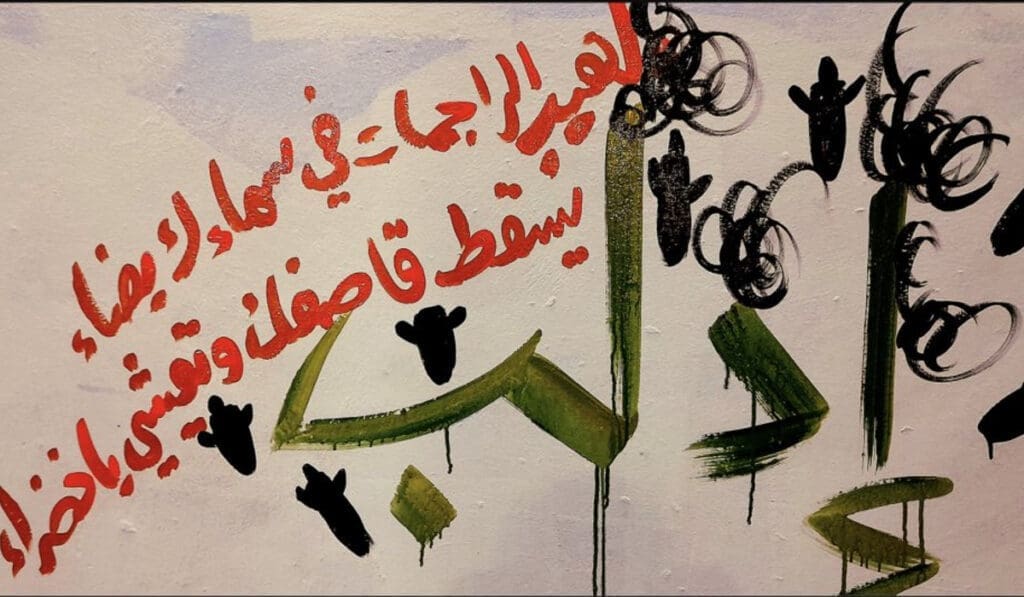

The Syrian opposition, which I firmly believe is still the majority of people in Syria, realizes this and sees Russia as an imperialist enemy. If it wasn’t for the Russian bombing, Assad would have lost the war, and that’s why Syrians are on Ukraine’s side. We see demonstrations in support of Ukraine in Idlib, demonstrators waving Ukrainian flags or painting murals expressing opposition to Russia’s war in Ukraine. There are even Syrians who would like to join the fight against Russia in Ukraine. It’s the same in the case of Chechens. On one side, the traitor of the Chechen people, Kadyrov, and on the other, Sheikh Mansur’s brigade, fighting on the side of Ukraine against Russia for the liberation of Chechnya.

BK: You mentioned Idlib. It is often seen in the West simply as a seat of terrorism, where there is no opposition to religious fanaticism. Could the current situation change this view of Idlib?

RY: I really don’t know if the West will change its mind. For this to happen, there must be public pressure in the West. That’s why we have to explain again and again that the situation in Syria is much more complicated. This is not just a jihadist fight against a secular government. There is a connection here between coming to terms with Russian crimes in Syria and Russia’s confidence marching into Ukraine and bombing cities in Europe. European powers have allowed Russia to bomb hospitals in Syria daily while building another Russian gas pipeline, and thousands and thousands of Syrian refugees are seeking asylum because of Russian bombs falling on their heads. Because we in Europe accepted Russian disinformation about Syria, Russia believed it could get away with its ridiculous pretext of “denazification” in Ukraine. But because Ukrainians are European, Christian, and white, it is more difficult for Russian propagandists to spread this disinformation. A number of people who spread this misinformation in the past are now silent.

As for Idlib and Syria, many locals have simply given up. It has been too much for them and they are focused only on basic survival. Not only in Idlib, but also in the territories controlled by Assad. The people are very poor, there is no economy, Syria is a captagon narcostate and is largely controlled by warlords linked to Assad, Russia, Iran, or other elements controlling the country. Ordinary people are exhausted and only care about how to get food or money for fuel to heat their homes in the winter. Most of the opposition people are in Idlib now, but we must not forget the issue of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which is an authoritarian jihadist group that controls Idlib. And of course there is the issue of Turkey. Most of the units that fought for the revolution against Assad are now under Turkey’s control and cannot act independently. People from the opposition are in various refugee camps or in Europe. It’s really very complicated.

We must also not forget that Russian imperialism is not only strangling Syria, but also Libya, the countries of the Sahel, and the Central African Republic.

BK: Do you see any connection between Russia’s involvement in Syria and Africa?

RY: Yes, at least in how Russia de facto controlled the migration flows of refugees from Syria and used them as weapons against Europe. The countries of the Sahel are deeply affected by the climate crisis; terrorism and violence are rampant there. It is likely that due to the collapse of states, drought, and related factors, we will see larger waves of people fleeing to Europe for safety in the next decade. With its presence, Russia can control these waves and thus control politics in Europe by sponsoring anti-immigration parties, which are often precisely pro-Putin and anti-European. Russia’s military defeat in Ukraine and its subsequent collapse would be good news not only for people in Europe, but also in the Middle East and the Sahel. It would open greater free space not only in these areas, but also in Russia itself. I hope for the defeat of Russia and I hope that it will be overwhelming.

BK: So could something like Russian decolonization take place?

RY: Yes exactly. It is decolonization. We can all agree that the US should not be telling Cuba or Venezuela what to do. It shouldn’t be telling them how to do politics or what military formations they should or shouldn’t be in. We all support the rights of these countries, even if they are dictatorships, to make their own decisions. In the same way, we must respect that Ukraine, a democratic state, can decide for itself about its economic direction or about its military allies. And it is absolutely imperialistic of us to demand that Ukraine make decisions based on what its larger imperial neighbor—which moreover colonized it in the past—thinks. Just as France or Britain are in the process of decolonizing their own cultures (not always successfully), Russia must also go through it. It is good and right that the British empire fell apart.

The same must now happen in Russia. Stretching from Japan to the Finnish border, this vast country is not one country. It’s an empire. All the countries around it, such as the states of Central Asia, must be more independent and democratic. Same for the states in the Caucasus and elsewhere. The more independent and democratic these countries become, the better and safer it will be for the world as a whole. That is why I hope for the defeat of Russia, a defeat as resounding as that of Nazi Germany at the end of the Second World War. I’m not saying I want to see Russian cities destroyed and millions of Russians homeless—I certainly don’t. But I hope that Russia as a state and as an empire will be destroyed. The inhabitants of Russia and the states connected to it will be able to live a freer and better life based on human rights and dignity for all.

BK: It could also be a chance for the West—a chance to more strictly respect human rights, dignity. It could also be a lesson for us. We accepted disinformation, we accepted people being killed by chemical weapons, we accepted annexation. The West itself has been the architect of false wars like the one in Iraq. This could be an opportunity to undo those mistakes and never repeat them again.

RY: I still hope so, but after what happened in Syria, I’m a little more cynical and pessimistic. I’m not sure people will ever learn. At the same time, in recent months we have seen how radically and quickly things have changed in Europe and the US. Still, in my opinion, they have not changed enough, and the first thing that should have happened was a total embargo on Russian gas and oil. Of course I know very well that price hikes will have an impact on the whole society and will bring many problems. However, we are in a state of war and I believe that the loss of three or four percent of GDP in Germany, with all the negative effects, is still a better option than total war. And that’s where we’ll find ourselves if we don’t stop Putin now.

BK: In the Czech Republic, we noticed a change in relation to the V4 bloc and to Orbán. Many rightwing politicians and journalists accepted and apologized for Orbán in the past. That is changing now…

RY: Good. It is good that people are starting to take politics more seriously and are slowly realizing that endless economic growth is not everything. I hope it will make us change our approach to China as well. China is a giant country, a powerful economy with a large population and a rich history, so it is inevitable and right that it plays a vital role in the world. But we have to realize that if we feed monsters, then these monsters grow and grow. This also happened in the case of the Chinese state. Of course, I don’t have a problem with China as such but with the Chinese state, which is not only imperialistic, but also genocidal.

It is impossible to have standard relations with China when we know what it is doing to the Uyghurs or to Hong Kong. I hope that today’s situation will make everyone think more about their politics, security, democratic values and what kind of world we want to live in. I also hope that our attitude towards misinformation will change. Now we finally woke up—when cities are destroyed in Europe, and we see millions of refugees who are white and Christian. Why did we accept the same misinformation when the refugees were Muslims from the Middle East? People need to wake up and take this opportunity to realize what values are important to us, and how we will prevent fascist and imperialist disinformation from spreading in the future, and how we will prevent our politicians from abusing this disinformation. But I confess that I am not very optimistic.

BK: Why not?

RY: It’s all partly due to the shocks we’ve experienced. Fuel prices are rising and, for example, in the United States, it is certainly not out of the question that Trump will become president again. Everything would be going completely differently now if Trump were president. The whole tragedy in Ukraine will drag on and Russia will change its positions. Politicians in the West will start saying why we should suffer economically and that Russia has the right to ensure its own security and the like. Everything looks better now, because Russia really underestimated the reaction of the West, the strength of the sanctions and the strength of the Ukrainian resistance. But we should learn well from all this and remember which values are the most important and not stop fighting for them.

BK: Why do you think the Global South is not very interested in what is happening in Ukraine, and why is Russia’s position relatively good in many countries of the Global South?

RY: The invasion of Ukraine is a clear example of imperialism applied by one of the most destructive empires in history. In this context, it should be mentioned that this is the same empire that harmed Muslim communities in Central Asia, and that committed brutal violence against the Muslim communities in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Syria. That is why it is so depressing to see that so many Muslim countries are unable to show solidarity with Ukraine and instead sympathize with Russia. It is important to say that we primarily hear what governments and elites think, not what the people think. Many regimes have their reasons for not angering Russia. Russia supplies weapons to the Indian army; in some African states the Wagner militias fight on the side of the government against insurgents or jihadists.

To a certain extent, however, the public in the countries of the Global South are automatically suspicious of the West, primarily due to their own colonial experience and current excesses, such as the disastrous occupation of Iraq. Therefore, they often prefer to believe Russian propaganda about NATO expansion. The West is paying for its past crimes and should therefore carefully consider its behavior in the future. We in the West should understand this primarily as a warning—we are entering an era in which the West is only one of many centers of power. If the West wants to gain the support and understanding of the rest of the world, it must demonstrate a willingness to cooperate and abide by international law.

At the same time, the responsibility also lies with activists and intellectuals in the countries of the Global South. They should fight against a simplistic view of the world that ultimately leads people to support one imperialism against another. All imperialism must be rejected. We must destroy the years of Soviet propaganda where, in the binary world of the Cold War, the Russian empire presented itself as a fighter against imperialism. It was never true and it is not true now.