Transcribed from the 6 April 2023 episode of The Fire These Times podcast and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

This narrative has developed more over time with the refugee crisis: far right groups saying that Syria is safe for refugees to return to, and there’s no reason why refugees should stay in Europe.

Joey Ayoub: Leila Al Shami is a British-Syrian writer and activist and a co-author of the book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War. She’s a returning guest of The Fire These Times.

Shon Meckfessel is an American writer and academic, and author of the books Suffled How It Gush: A North American Anarchist in the Balkans and Nonviolence Ain’t What It Used to Be.

Shon and Leila co-wrote a chapter on the links between white supremacists and the Assad regime as part of the book No Pasarán: Antifascist Dispatches for a World in Crisis edited by Shane Burley, who was also a recent guest.

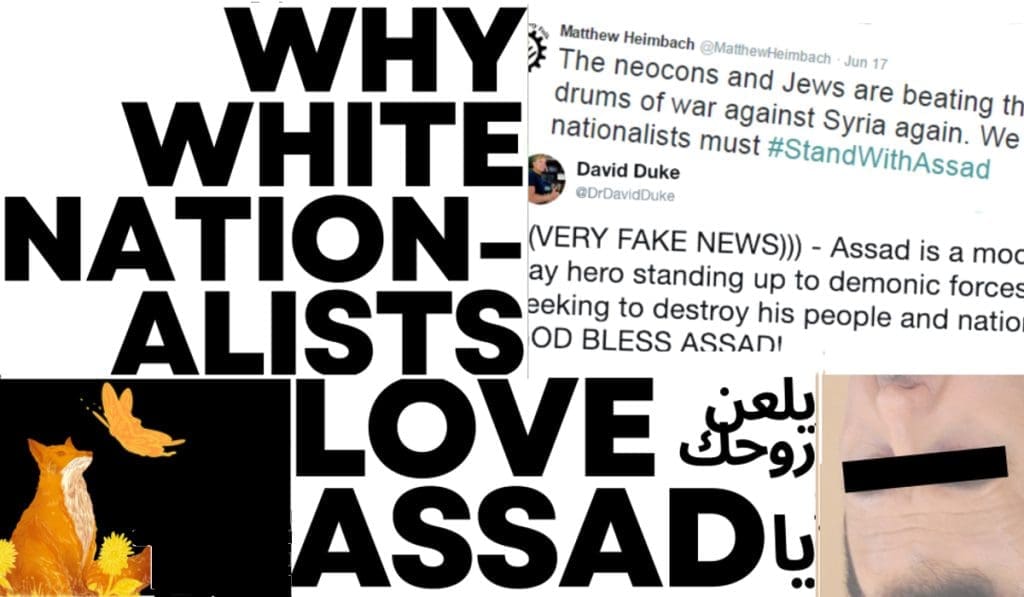

Mariam Elba helped us a lot with research for this podcast; unfortunately she could not join us. But she’s written a number of pieces for the Intercept about the Assad regime, including one in 2017 called Why White Nationalists Love Bashar Al Assad.

How are you two?

Leila Al Shami: Good, nice to be back.

Shon Meckfessel: Doing alright, all things considered.

JA: Can you walk us through an overview of this chapter and why you got into it? Why did you write it for this book and how did it come to be included in the international section of No Pasarán?

SM: Reading through the book, I was really impressed that Shane Burley found so many of my favorite voices through so many different scenes and specializations and brought them together. It took quite a while, it’s a book of some scope. But nearly every chapter at some point mentions something about the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, 12 August 2017. That’s also how ours begins, so there’s a throughline. When this moment hit, the United States realized we were up against a new political formation that many people didn’t see coming. A lot of us who follow developments of the far right had seen it coming for a long time.

The aspect of it that we focused on was James Alex Fields, Jr., who was the member of Vanguard America who ran his car into a group of protesters, killing Heather Heyer and critically injuring a number of other antifascist protesters in that rally. A lot of journalists who didn’t see this coming flocked to get information they could about him, and they saw on his Facebook page that his latest post was a picture of Bashar Al Assad with the word “Undefeated” underneath it. We saw the general public reaction, which was like, “Wait, what?”

It didn’t gel with a lot of the mainstream understandings of what is behind far right activism. Bashar Al Assad is Alawi, but that’s essentially Muslim. He’s an Arab, and doesn’t immediately fit the notion of a heroic figure for far right racists. That was a launching point for our chapter: to propose an answer to how this fits in, how it is actually quite consistent. It shows us a lot about the constitution and composition of the far right that belies the traditional liberal notion that racists and fascists are just willfully ignorant and insufficiently cosmopolitan. Fascism has its own cosmopolitanism that we need to attend to if we’re ever going to stop it.

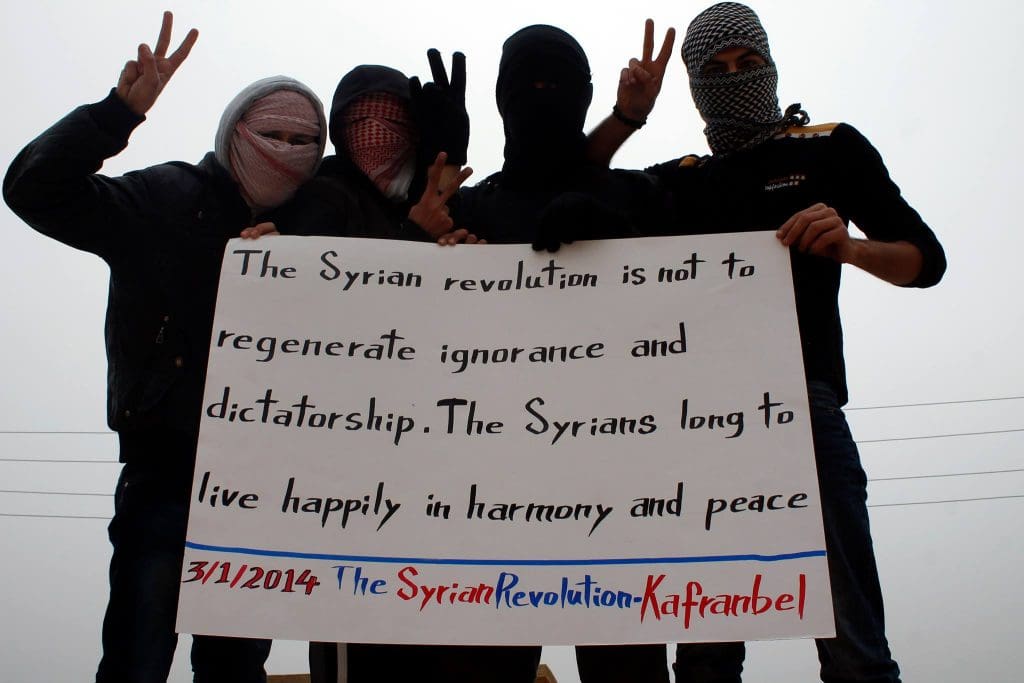

LS: I first started looking at far right support for Assad in 2013; I wrote an article focusing mainly on European fascist movements. We’d seen during that period a lot of solidarity delegations going from European fascist parties to Syria. I was very interested in what the reason for that was. Why was the far right in Europe identifying so much with an Arab Syrian dictator?

Also in that period, we saw across the Western world a real resurgence of the far right; it was getting more and more power and influence. The alt right was very big in the US. A lot of that energy brought together Donald Trump and Brexit in the UK. Brexit was not a fascist movement, but these things were very influenced by Syria and the Syrian refugee crisis; that gave a lot of far right movements and nationalist tendencies in Europe impetus to mobilize. I was quite interested in what the connections were between Syria and this far right revival.

JA: In some sense, the three of us met around this disbelief and then growing anger, not just at what was happening in Syria proper, which is an entire level of anger in itself, but at seeing, especially on social media (this would have been 2014-15-16) figures that we would associate with the “far left” saying stuff about Assad that falls into the usual “anti-imperialism” (which I’ve discussed ad nauseam on this podcast and elsewhere). But the majority of support for Assad was coming from the far right.

It was a confusing thing at first, at least for me, seeing the delegations you mentioned going to Syria. I estimate about eighty percent of them were on the far right and around twenty percent of them were on the “far left.” These included the vice presidential nominee for the Green Party in the US, and a number of figures on the far left in Spain. And of course in France there was Melanchon, and obviously in the UK the figure of Corbyn and, even more notably, people around Corbyn.

It was very disorienting and then infuriating to see the obvious connections between the far right and Bashar Al Assad being denied by large swathes of the left. This is what prompted Mariam Elba to write that piece for the Intercept, as a response to the growing understanding among people who research the far right: anarchists, antifascists, scholars, and activists had been seeing this grow more and more. One thing we do more often than many other folks is take the right seriously and take what they say seriously. “When someone tells you who they are, believe them.”

As a way of anchoring this conversation, how have you seen this phenomenon evolve over the years?

LS: We saw visible support from a lot of far right parties in Europe such as the National Front in France, Casa Pound in Italy, Falanga from Poland, and the British National Party putting out statements in support of the Assad regime, and going on “fact-finding missions” to Damascus, where they would report that everything in central Damascus is fine, there aren’t any problems there.

This narrative has developed more over time with the refugee crisis: far right groups saying that Syria is safe for refugees to return to, and there’s no reason why refugees should stay in Europe. There were different groups involved in promoting that narrative. There’s a French NGO, “Christians of the Orient,” with very strong far right connections, which actually works with refugees in Lebanon, and it’s been sending delegations to Syria. Also, you might have seen these travel vloggers more recently who have been going to Syria and saying everything is safe there: when I watched a couple of those videos, I saw that they were being hosted by Christians of the Orient. They were the people taking them around.

We’ll talk more later about why the far right identified with the regime as a fascist regime.

SM: Two developments have really come into a more clear outline since we became friends and got to know each other and have been working on this stuff. One is that a lot of those agents are really directly state-sponsored: people like Ben Norton and Max Blumenthal have certainly taken a paycheck; there’s Mint Press News. It’s not a coincidence that they seem to be doing quite well, and those of us working on the critical-of-power side still have to have day jobs. Some of those numbers have come to light; we’ve seen a number of exposés about their direct state sponsored ties, let alone access to state resources such as RT and innumerable other Russian-sponsored and, to a lesser extent, Chinese state-sponsored media outlets and other discursive resources.

Also the troll factories factor in, as a lot of us suspected, interacting with people online and doing pile-ons with a lot of accounts using the exact same lines. The research has come out showing that we were not only dealing with well-intentioned naive people coming from a good place, but that we were often dealing with people paid to create that noise, and that’s part of the model.

Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine, which began about a year ago in its intense phase, has highlighted that, because a lot of Russian resources are being diverted to that and we’re seeing a lot less of the opposition than we had grown used to over the last eight years. These things that we had suspected were coming from state-sponsored resources really were, and as those resources are getting diverted, the noise is going away a little bit.

Another thing that we’ve worked out in our conversations, and other scholars and activists have made more sense of, particularly with the role of the left in this, is that we’re in a changing world. The United States still does over half of the military spending in the world at any given time, obviously still has hundreds of bases around the world, and to be clear is still enacting colonial projects. The New York Times had an article this week about how the US is bolstering its presence in the Philippines in view of pushing back against Chinese power. At the same time, this is in a larger post-Cold War context where, particularly as the effects from the 2003 war on Iraq come home to the US and as the country reels from so many economic effects from that (and, one would like to think, moral effects, though probably less so), things are changing. But we still have this historical formation–these institutions, identities, social networks, and people’s social capital tied up in opposition to Western imperialism–not sure what to do with itself.

In the Syria conflict, in 2015-16 as Russia was amping up its involvement, it happened upon this happy coincidence of alliance with the social momentum of internal opposition to US dominance, and then focused its approach and started sponsoring it more directly over time.

There’s also the example of the European New Right. I come at things from the discourse perspective: the European New Right and Aleksandr Dugin in Russia have articulated a whole discourse about claims for LGBTQ rights, claims for human rights, claims for gender diversity and antiracism (essentially egalitarian claims) being Western cultural imperialist impositions. Even though one would think that Western leftists would want to protect egalitarian claims, because that’s what the left means historically, a lot of the social institutions and identities tied up in opposing the West, in this time of crisis where they’re not quite sure what to do with themselves, actually see these New Right and Duginist claims as a way to still stand against Western imperialism and keep doing what they’re doing. Obviously one would hope people would see the contradictions there.

Eight years ago when we started talking actively about this, we had a hunch, but these things have come into starker relief as the research has come out and as people have outed themselves more directly about where they’re at.

“Why is it that in places like Syria and Lebanon, we don’t get to have class struggle while the UK and the US and Germany get to fight against the bosses? Why do we have to follow our bosses just because our bosses are allegedly an Axis of Resistance?”

JA: That’s one of the main things I remember about that time: when we would point out that these things were happening, that there is this growing link between the far right and Bashar Al Assad, a lot of otherwise reasonable folks interpreted all of this as either conspiracy theories or as me being “biased” because I’m against Bashar Al Assad–as seeing things that are not there, even when I would directly show a photo of a fascist or a white nationalist (especially in the US but also in Europe) with a photo of Bashar Al Assad or a Hezbollah flag, as with Matthew Heimbach for example.

As antifascists and anti-authoritarians, one of the main things we do is understand our enemy. We need to understand why it is the case that this thing exists and appears to be growing. In many ways, this invisibilization of Syria and the discourse related to fascism and antifascism has been part of the problem, in the same ways as genocide denialism with regard to Bosnia or Rwanda or Cambodia is also part of what gets recycled today. We see this on the far right especially when it comes to Bosnia, echoed in their apologia of Vladimir Putin and Bashar Al Assad.

They make those links. They have always made those links. They make the links between supporting Serbian ultranationalism and supporting Vladimir Putin and supporting Bashar Al Assad. Some of them will have internally coherent but externally bizarre-looking ideas; some of them will love Bashar Al Assad, and some of them will say he’s just some Arab in the desert and they don’t like him. A big part of the problem is the idea that if something doesn’t make sense, or is not “logical,” then it can’t quite be that way.

Someone like Kanye West saying stuff about Jewish people and that he likes Hitler makes a lot of people confused because this is a Black man–how can he say stuff like that? But it doesn’t have to “make sense” for it to be something worth paying attention to and opposing. The same happens with the far right and Israel. Some are pro-Israel and some are anti-Israel. Those who are anti-Israel are usually so because they are antisemitic, not because they are anti-Zionist. Some of them will say they are anti-Zionist, but it’s just an expansion of their antisemitism. Being anti-Zionist does not mean we should confuse that and support those people.

The far right is not a unified movement, thank goodness. Part of the danger is when it becomes more unified, when they do have those transnational links, as we saw with Identity Evropa, or the Proud Boys in Canada. The best way to oppose the links they are trying to build is to understand what it is about those links that unites them. The link with Syria is something I wanted us to focus on. I don’t want to focus too much on the far right in the US, we’ve done other episodes on that–but specifically the link to Syria. Why do they give a shit?

Syria being rendered invisible has made antifascist responses weaker, and it’s made a normalization of Bashar Al Assad a de facto hegemonic reality, which we see to this day. We’re recording this show three days after the earthquake in Syria, and we saw an outlet like Progressive International and a bunch of other people on the left saying that the main thing preventing reconstruction and aid in Syria is the sanctions on Syria. While the sanctions should be part of the nuanced and complicated conversation, it’s obviously not that straightforward. The vast majority of places that are now ruined, were destroyed by Bashar Al Assad long before the earthquake. It’s much more difficult to survive an earthquake if your building was already damaged by a barrel bomb or by the Russians beforehand. This is the case for many folks in Aleppo, for example.

What do you make of the invisibilization of Syria, with discourses around antifascism not really talking about it (with the exception of when it’s about Rojava and opposing the Turkish government, which should of course be opposed)? Why has Syria been invisibilized, in your view? And what are the consequences of that?

SM: There’s a lot there. In a way, it opens up the central question of the chapter, so we’ll come back to different aspects of it. One question we had at the heart of this was what attracts people to analogies to other issues around the world–including our enemies? You were talking about the contradictions that are often seen in some on the far right taking Arabs and Muslims as exemplars while someone else in the movement doesn’t really like them. From a cultural studies framing and base of analysis, it’s more about what the discourses do for people. Working class white people in the United States cheering on police and having a Blue Lives Matter sticker on their car–those people are actually getting killed by police too. It’s a lower rate than Black people, or BIPOC people in general, but at the same time in the United States even white people get killed at significantly higher rates by police than in most other industrialized countries. But it’s the active identification with power that they are latching onto.

That’s one way to answer these questions. Some of our chapter gets into the example of how the Assad regime’s open genocidal policies against its own people are something enviable to people on the far right. It’s a naked, unapologetic exercise of the starkest inegalitarian politics you could ever have, that’s not beholden to any sort of moral compass. It’s the absolute freedom of the state, so for people whose politics come from this identification with the state, a state’s genocide against its own people, completely unrestrained, is the highest form of freedom. Of course the Assad regime has excelled at that practice.

It’s also important not to just stick with that, because it can bolster the clichéd liberal view of this as mere ignorance: “they’re so stupid they don’t even see the contradictions.” A lot of it is very consistent and rational. We get into the history of Mussolini’s foreign minister Corradini: he came up with the theory of proletarian nations versus bourgeois nations. It’s not that the theory doesn’t make sense. It’s clearly consistent as a political philosophy. It’s one that essentially, in the end, justifies inequality within those societies, but it’s not “stupid.”

It reminds me: at one point when I was in Beirut I was interviewing a wonderful group called Socialist Forum, and they said, “Why is it that in places like Syria and Lebanon, we don’t get to have class struggle?” The only conflicts, the only struggles they’re allowed to participate in are the anti-imperialist ones judged from the Risk-board view of their countries, which is to say from the state level. They ask why all these alleged Marxists don’t allow them to have class struggle while the UK and the US and Germany get to fight against the bosses. “Why do we have to follow our bosses just because our bosses are allegedly an Axis of Resistance?”

I just want to emphasize that this is a politics that is consistent and rational. It’s evil, and it’s starkly inegalitarian, but it’s not dumb. It’s not even really contradictory. I want to pass to Leila too; in terms of Syrian history, it comes from a long tradition.

LS: Definitely, the far right sees in the Baath Party, which is the ruling party in Syria, a historical continuity with national socialism or with fascist movements of the twentieth century, because it shares characteristics with those movements. There is the authoritarianism of the Syrian regime and the cult of personality around the president, which is very strong and very reminiscent of totalitarian regimes–not only the fascist regimes of the twentieth century but also Communist regimes.

When the Arab Socialist Baath Party came to power in 1963, it came to power on a platform which combined Arab nationalism and Arab socialism, both of which were witnessing a large resurgence in the wave of decolonization. The Baath advocated for the unification of the Arab countries into one Arab state led by a Baath revolutionary vanguard. If you look at the 1973 constitution, it says that the Baath party is the leading party in society and state.

And the Baath really mythologized the idea of the Arab nation. It was a very romantic vision of past glories, which was a way to counter the humiliations that the Arab world had suffered under French and British colonization. It was a very secular party, so it attracted a lot of minority groups, and it advocated socialist economics but rejected the Marxist conception of class struggle (as Shon said). Going back to this idea of the Italian fascists, the Baath saw that all the classes amongst the Arabs were united in opposing colonial domination by imperial powers, so that nations (rather than social groups within nations) were the primary site of struggle. That’s interesting, because we see that idea coming more and more into the left. When we see more and more people on the left advocating for multipolarity, we see those ideas.

It was very top-down socialist economic planning, based on the Soviet model: nationalizing major industries, doing large infrastructure development, and redistributing land away from the landowning class. It was these populist policies that really won the Baath party cross-sect peasant support, which it obviously lost later on when Hafez Al Assad and particularly his son Bashar Al Assad implemented neoliberal economic policies, once again shifting the economic balance and dynamics.

Assad came to power through an internal coup within the Baath party, which was a purge of the leftwing faction of the Baath party, and either got rid of or co-opted the left. Some parts of the left joined the ruling coalition. The ones that wanted to remain independent were wiped out. It also got rid of all kinds of free unions and independent associations, and started setting up parastatal organizations which were said to represent the interests of workers and students and so on. There was this indoctrination of the population through these Baath-controlled organizations around the Arab nation.

For example, in schools there were two Baath parties. There was the Baath Vanguard, which all primary school children had to join, and there was the Revolutionary Youth Union, which all secondary school children had to join. That was very much a vehicle for promoting Baathist ideology and promoting Arab nationalism.

Hafez Al Assad built a totalitarian police state where there was tripartite control of the state by the Baath party, the security apparatus, and the military. But in reality the power was centralized in the presidency, in the person of Hafez Al Assad, and there was a big cult of personality around the president. People were made to attend choreographed spectacles of adoration for the president. There were pictures of the president everywhere in Syria. You still see those today with Bashar.

There’s a lot of factors which are reminiscent of fascist movements of the twentieth century that the far right identifies with. And the far right’s interest in Syria goes back. In 2005, there was a visit to Damascus by David Duke. He gave a speech on Syrian state television. He said, “We really identify with Syria, because the US is occupied by Zionists in the same way that your country in the Golan Heights is also occupied by Zionists.” So there is some affinity; the regime represents something that the far right clearly identifies with.

People will accept the completely unrestrained violence of the state in cracking down and exterminating an Islamist threat. Assad was very clever in how he used that.

JA: You mention how a core ideology of the rightwing faction of the Baath party, the one which won out in the 1970 coup by Hafez Al Assad and his allies, has this logic of a hollowed-out leftism. I’m not sure what to call it. I recently did an interview on multipolar imperialism with Kavita Krishnan, Promise Li, and Romeo Kokriatski. Kavita Krishnan was part of one of the main communist parties of India, on the politburo for twenty years, but resigned late last year over the question of Ukraine.

What I found interesting about these dynamics is the same reason why, for example, a community like Syrian Palestinians, especially around Yarmouk, are ignored or erased in “anti-imperialist” discourses: because they don’t quite fit the narrative of being both against Israel (they are Palestinian refugees from the time of the Nakba or slightly after) and also being anti-Assad (being part of the areas of Syria that rose up in 2011). Those seeming contradictions become contradictions in the minds of people who adopt a simplistic anti-imperialist worldview, but this can only be possible if they have no analysis of class, no analysis of power, or of the state for that matter–if, indeed, they adopt the Baathist version of “leftism” or some kind of socialism hollowed out of any class struggle. I’m not a class reductionist, but class is one of the factors to take into consideration, obviously.

I find this very interesting and distressing, because in some sense this is the rulebook that was played against us in the Middle East. You mentioned 1970, but the Iranian revolution of 1979 is another good example of a very vague populism that’s sort of left-ish but doesn’t have any kind of class analysis, doesn’t have any kind of actual social justice, and at the same time always targets internal threats first, which more often than not means the local left. In Iran, obviously, that included the persecution of Iranian communists and other Iranian leftists, which continued even during the Iran-Iraq war. In Lebanon as well, when Hezbollah was gaining ground, they started by assassinating very well-known Lebanese Marxists and communists in the south who were themselves Shia, because they saw them as the primary opponent. They literally played out the Iranian rulebook in Lebanon.

I find it very depressing that we can have literal Syrian communists today, like Yassin Al Haj Saleh (who is a friend of ours) and his wife Samira Al Khalil, who both participated in communist related actions in Syria and both were imprisoned for that reason for extended periods of time, who are not invited into the great halls of leftwing organizing in the US, among the groups that tend to have more resources and are proposing a supposedly alternative vision of the world that is more just. They are reifying the same kind of authoritarian logic that they say they oppose at home, somehow finding no problems supporting it abroad.

All of this is a segue into respectability politics. Because it’s one thing to oppose the far right, and oppose the far left when it does the same things, but there’s this kind of respectability politics around Bashar Al Assad. Bashar was close to a lot of Western powers in the same way Qaddafi was close to Berlusconi and so on, and he very much played on the idea that he is the strong man who is a bit more tolerant (especially in the early 2000s), who is secular, who is the one keeping at bay groups like the Muslim Brotherhood and that sort of thing.

This is one of the aspects of the research that Mariam helped us remember: in February 2011, just before the revolution really kicked off in Syria, there was a notorious profile of Asma Al Assad in Vogue magazine, with sentences I am going to quote. The title was “A Rose in the Desert.” Asma is described as “glamorous, young, and very chic. The freshest and most magnetic of first ladies. Her style is not the couture and bling dazzle of Middle Eastern power but a deliberate lack of adornment. She is a rare combination: a thin, long-limbed beauty with a trained analytic mind, who dresses with cunning understatement. Paris Match calls her ‘the element of light in a country full of shadow zones.'”

SM: No racial connotations there at all!

JA: None whatsoever. On the one hand, there’s Vogue itself, but then there’s Paris Match; Bashar Al Assad took selfies with Sarkozy and other European leaders. This was always the thing: “He speaks English very well; his wife is British-educated; they’re very sophisticated.”

LS: “He’s a doctor.”

JA: And that’s quite literally what David Duke himself said on Twitter before he was permanently banned: he was praising the family of Bashar Al Assad and the first lady, and, during the Obama presidency, contrasting how “white” they looked in comparison to Barack and Michelle Obama.

David Duke, to be honest, wasn’t paid much attention. But those early signs were then picked up when the alt right, Steve Bannon, and all of that shit became more hegemonic, and of course catapulted when Donald Trump became president of the US.

Can you comment on this idea of respectability politics and how it intersects with what we are talking about here, in relation to Bashar Al Assad having this respectability aura around him and how it is still working?

SM: I think we should go back to Yarmouk in a minute, which is a separate topic. But Yassin Al Haj Saleh said it best: it was a very smart public relations move, on the Syrian regime’s very conscious part, to contrast what Yassin calls “fascists with ties” with “fascists with beards” by highlighting Daesh/ISIS and, as Leila has written about extensively, by the intentional campaign to release the more extremist Islamist fighters from prisons while secular or multi-ethnic activists were being tortured to death. This was a conscious strategy to appeal to respectability politics by contrasting them with openly racist tropes about more traditionalist mujahideen.

We’re using this term respectability politics, and I think it’s helpful to see the way that terms and discursive concepts can travel. This is a hot term right now because it’s from the left, particularly Black Lives Matter, beginning in 2014-15 with a generational struggle within Black politics in the US turning against a lot of the commonplaces from the Civil Rights Movement–things often falsely and unfairly attributed to Martin Luther King, but other things truly so. For example, Rosa Parks was chosen as a conscious figure because she had a clean record. She was the third Black woman in the Montgomery bus boycotts to do this, but the first one was a pregnant teenager and the second had an alcoholic father so they were worried they weren’t going to be sufficiently presentable. This was true of the lunch counter sit-ins to a lesser degree, and a lot of the figures of the Civil Rights Movement were college kids, were middle class Black people, were well-educated, and there was a move to distance the issues from the majority of people who were impacted by it, because the strategy was to present an easier image for white people to accept.

I teach in my classes the film Thirteenth, which I think is the best single source for this whole story and has a lot of wonderful scholars in it. The problem is that as those Jim Crow laws and the legal apartheid systems of the United States transitioned to police discretion and DA discretion and the “war on drugs” and a lot of racialized practices rather than openly racial legal language, respectability politics came to reproduce a lot of that oppression. There’s a hip-hop song called “You Put the Shame on Us.” It ends up accepting rather than rejecting the shame that was put on Black youth and Black working class people and the underclass by only showing the Bill Cosby “pull up your pants” phenomenon. Things that came from a previous wave of antiracist struggle end up being very useful tools to reproduce racism in the new one.

It’s interesting to think about the quite recent history of the term respectability politics–it’s only said in a critical sense. Nobody says, “I believe in respectability politics!” It’s always a term meaning that you’re reproducing your enemy’s stereotypes while trying to fight them or wage larger battles. In terms of the right, what we’re really talking about is making things that have been unspeakable permitted within the public discourse.

Leila wrote a great portion of our chapter about the role of conspiracy theory. When I was in Syria, I lived in Yarmouk for some months before the revolution and war, and it struck me that in Syria at the time the ruling ideology was conspiracism. Ryszard Kapuscinski, in his book on Iran after the overthrow of the Shah, has a really beautiful interview with this guy who, in his explanation of phenomena, is going so out of his way to not say the concrete things that are right in front of his face. That’s because under the Shah, and under Bashar Al Assad now, it’s extremely dangerous to speak openly about these things that are very obviously making your life bad. But you have to say something, so conspiracism in that context will fill this role of being able to articulate your emotions and put them into words and communicate them to others, even if the vehicle for that is obviously silly. Israel didn’t make your coffee cold this morning.

You can’t actually say the things that you know are making your life miserable, so you have to find another way to say them. That’s why conspiracy theories were the ruling ideology in Syria when I was there before the revolution. In the US, it comes back to when we talk about respectability politics: it’s another side of the same function as conspiracism. What the far right is doing is Trojan Horse-ing into discourse things like “maybe certain people are biologically inferior,” “maybe the world would be better off if we just exterminated certain people.” Those are not okay ideas after the Holocaust. But if you displace them into this faraway place that people don’t know that much about, and if you justify them by saying Assad is really fighting Islamic terror just like we are, it suddenly makes those things sayable.

Now the right can claim a victory in having shifting the Overton window, as they say, to the right. There are a lot of things that are sayable now, in a very anti-humanist and starkly inegalitarian way, that were not polite things to say a decade ago.

LS: A lot of the appeal of Assad, not only on the right but also on the left, is that he’s seen as a secular leader. This is linked to Islamophobia and “war on terror” discourse, where terrorism is totally equated in the popular imaginary with Islamism. What we’ve seen is that people will accept the completely unrestrained violence of the state in cracking down and exterminating the Islamist threat. Assad was very clever in how he used that. He took steps which facilitated the Islamization of the opposition. Many key figures in some of the most hard line Islamist groups were actually imprisoned by the regime in 2011 but were released and went on to form some of the hard line military battalions that emerged particularly after 2013 and 2014.

Assad knew that by creating and facilitating the specter of Islamist extremism that he would get support from two constituencies. One was an internal constituency: he knew that it would frighten minority groups within Syria into support. They might not have like Assad but they may have feared what was portrayed as the alternative to Assad even more. And the second thing was to create international support for his campaign of extermination (which is what the UN called Assad’s waging war against the democratic opposition. It was a policy of extermination). He really knew that people would stand beside him if he was seen as the secular leader combating an Islamist threat.

And as Shon mentioned, Yassin said that there’s the fascists with the neckties and the fascists with the beards, and people are going to turn a blind eye to the fascists with the neckties if they’re seen to be combating the bearded variety, which is always seen as a greater threat. He played on that. He knew how to portray his desire for power to an external and an internal audience, and it worked.

Many times I’ll see on social media people who claim to be on the left saying, “Look at Damascus, in Damascus there are women out in nightclubs, in Lattakia there are women on the beaches wearing bikinis, but if you look at the opposition areas, all the women are covered.” All of these Islamophobic tropes are being brought into play in service of preserving or supporting the regime.

JA: Unfortunately we had some technical issues while recording this and it seems that the last ten minutes of this conversation just disappeared, no idea why. Sometimes technology just fails us.

I’ll briefly say that we ended on an optimistic note. Thank you for listening.