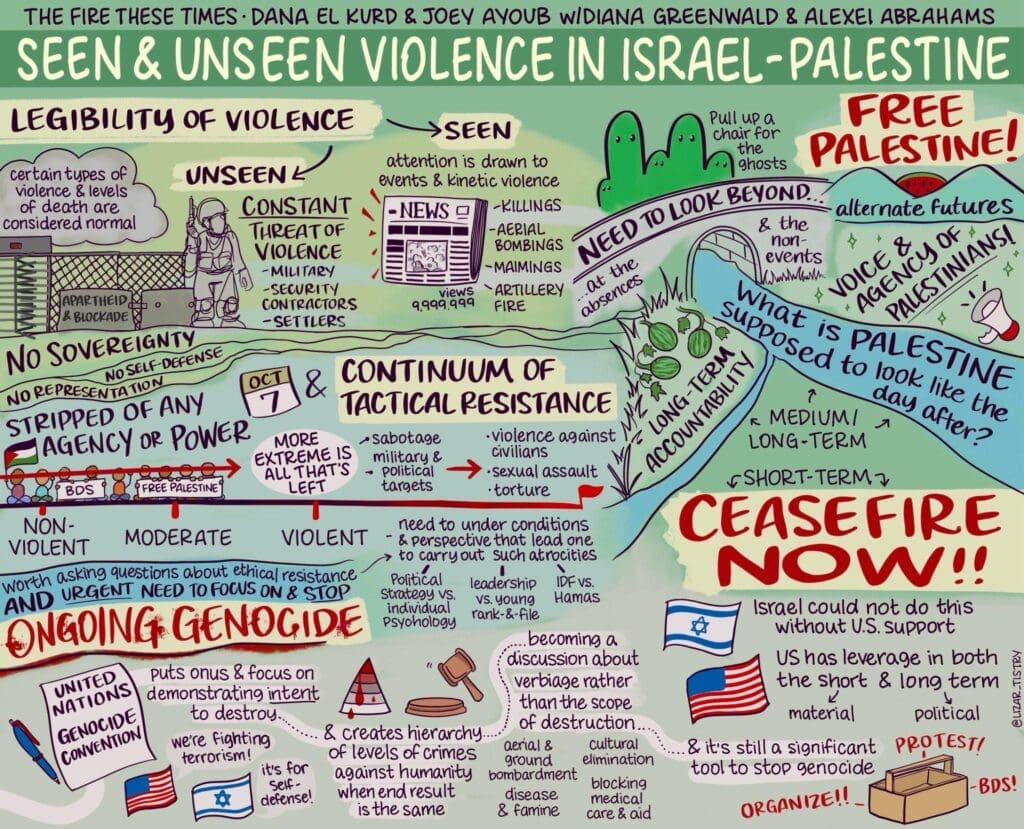

Transcribed from the 14 December 2023 episode of The Fire These Times and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Don’t miss the beautiful infographic at the bottom of this post!

Listen to the whole conversation:

A missed destiny is not like a fork in the road. You don’t get to forget about it. The lines run parallel, so you live in full view of what your life was supposed to be in the absence of the Nakba or in the absence of occupation, were it not for this wall or this fence that divides here from there. It’s torturous to live in full view of that and to realize what your life could have been.

Dana El Kurd: Hello – my name is Dana El Kurd, and I’ll be co-hosting this episode of The Fire These Times. We recorded a conversation with Alexei Abrahams from McGill University and Diana Greenwald from City College of New York about violence in Israel-Palestine, in Gaza, and in the West Bank, and how we can understand this violence, categorize different types of violence, and contextualize it.

We thought it was important to do this because, given the scope of the devastation in Gaza, obviously there is a lot of focus in the media on the level of destruction and the human cost of what we’re seeing in Gaza. And of course we should be focusing on that. But there is a tendency in the discourse and in the media to decontextualize what we’re seeing, and not appropriately situate what’s happening in Gaza in the context of the broader trends in Israel-Palestine, including in the West Bank. If we focus on just the short term, we might miss crucial elements of understanding the broader context. So we thought it was important to have this conversation. We hope you find this episode productive.

Joey Ayoub: Let’s start with some introductions alongside a general question that we are now asking all guests: How is your heart?

DK: My name is Dana El Kurd. I’m a researcher and writer on Palestine and the Arab world. We have two guests with us today for this episode: Alexei Abrahams and Diana Greenwald. Alexei, do you want to introduce yourself and let us know how you’re doing?

Alexei Abrahams: Sure, thank you, it’s so great to be here. My name is Alexei, I am the digital trace team lead at the Canadian Media Ecosystem Observatory at McGill University. I study political communications. I have also studied the Palestinian struggle all of my adult life. These past few months have been very hard. My heart is heavy. It’s difficult to watch, as a sympathizer of the Palestinian struggle, as a person of color during a period of incredible dehumanization, and also as a scientist, as a researcher, during a time when it feels like there’s such contempt for knowledge and expertise.

Diana Greenwald: Thank you so much, Dana and Joey and Alexei, for being here. I’m Diana Greenwald, I’m an assistant professor of political science at City College of New York, and a longtime colleague, friend, and comrade of Dana’s and Alexei’s. I study Palestinian politics primarily at the town/city/village level in the West Bank using a political economy lens.

These past couple months have been shattering. I’ve been relying on lifelines of people who are knowledgeable and compassionate, like Dana and Alexei and other friends, other scholars, other people in the region. I’ve been trying to rely on those relationships more than getting immersed or embedded in social media discourse and the hot takes of the moment (more or less successfully depending on the day).

It’s really hard to have any perspective or to step back right now, as a scholar or analyst, because everything is unfolding minute by minute, so rapidly, and it’s really horrifying.

DK: It’s really difficult in this researcher identity that we operate in, because we’re also human beings. It’s very difficult to be so detached, as if this is just a political science question unfolding.

Could you describe the conditions of violence before October 7, Diana? The reason I’m asking you first is because of your piece and your continued work on “indirect rule.” Maybe you could explain those concepts too. What was violence like before October 7?

DG: This is a deep topic. When I think of violence under military occupation, for example in the West Bank, where I have done essentially all of my empirical work, I think of not just the use of it—like actual killings or maimings or destruction of property or abuse in prison, which are obvious manifestations of violence that occur every day against Palestinians in the West Bank. There’s also intimidation. There is settler violence that might not be fully carried to fruition physically, but that threat and intimidation is always there. There is regular intimidation from the Israeli military. Within our understanding of violence we have to think about the threat of violence or intimidation that constantly persists.

Even if someone is not wielding an AK in your face or steamrolling through your village in a tank (which of course also occurs), there is a constant understanding that agents of the Israeli state—whether military or security contractors (which are also prevalent in the West Bank) or settlers—are wielding the means to commit violence at all times. Even just day-to-day interactions at checkpoints or, if we return to Gaza, interactions required to come and go from the territory, things of that nature—it’s all backed up by this constant threat of violence.

Of course we all experience that if we have police forces and militaries and state agents of coercion in our lives. But the point of occupation is that the occupied population is in no way represented or possessing any means of accountability, control, or influence over those agents. It’s an obvious point, but that’s my summary of thinking about violence under occupation.

DK: That’s very valid. The reason I brought up the term indirect rule is because a lot of people—sometimes in bad faith and sometimes not—think that Palestinians have some level of self-governance in these urban centers, or in the Gaza strip, so wonder how this threat of violence or these modes of violence could persist.

Alexei, do you want to jump in here? How would you describe conditions of violence before October 7?

AA: I’ll lean on the words of Ghassan Kanafani, as I translate them: “It seems to me my life and all of our lives are as a line, trudging in silence and shame, beside the line of our destiny. But the two lines run parallel and shall never meet.”

When Kanafani writes this, he is talking about the violence of the Nakba that separated Palestinians from the life they were going to live, the life they were supposed to live, their destiny, and set them on this separate track. But a missed destiny is not like a fork in the road. You don’t get to forget about it. The lines run parallel, so you live in full view of what your life was supposed to be in the absence of the Nakba or in the absence of occupation, were it not for this wall or this fence that divides here from there. It’s torturous to live in full view of that and to realize what your life could have been.

That is the structural violence of living under apartheid or occupation or colonialism. And it’s so hard to see if you’re not from that context. It’s so illegible. It’s not even racism—it’s just that human nature struggles to recognize absence. There is so much in Palestinian literature—We must pull up chairs for the ghosts; Let the ghosts speak; Let the silence speak—that is just wrapped in absence, this sense of loss and absence, this ghostliness.

The violence of the last two months has been shattering, as Diana said. But it’s so dramatic, action-packed, it gets covered by the news, because it’s a bunch of events. But what we were missing before that, on October 6 and all the days before, is the day-to-day humdrum of structural violence that leaves us living with ghosts.

DK: And not just the ghosts of people who should be there and are not, but the ghosts of what your life could have been. I don’t even live in the occupied territories, and I’m a very privileged person—I live in the United States—and I think about that all the time. What could I have been doing if I weren’t Palestinian? Or if I were not constantly under assault? What other potential lives could have been?

JA: I would describe it as a form of haunting, these alternatives. Hauntings are usually understood as a thing from the past that is haunting the present. But it’s also parallel presents that could easily have been but are not, were it not for X, Y, and Z. A visual example for me is that when I’m in southern Lebanon, Haifa is closer to me than Beirut is, physically. My grandfather was originally from Haifa. This clicked in my mind when I was there—I used to enjoy opening Google maps and seeing where things are, and I realized just by zooming out that Haifa pops up before Beirut does. And to this day that’s something I can’t quite wrap my head around.

In Murder on the Orient Express, it’s taken for granted that you could take a trip from Jerusalem via Syria or Lebanon up to Turkey and then into Europe. For me that is much more mind-blowing than the actual murder mystery of the novel. That’s what it is for me: the precarity of the present, and how it could easily not be this, it could be something else. It’s been two months now, and October 7 could also not have happened and we’d be having a different conversation, or none at all. What I’m trying to say is that nothing is written in stone.

Concretely: I’ve brought this up a few times, but my daughter was born a week after October 7, on October 15, as a premature baby, a micro-preemie. All of the news that we saw from the hospitals, in al-Shifa in Gaza, of the premature babies—I was reading it differently. At the end of the day, had things been different, my daughter could have been there. Had things been different—maybe my grandfather wasn’t from Haifa but from Gaza, stuff like that. And maybe the difference between him being in Haifa or Gaza is his father or his mother decided to move somewhere at some point, or decided to settle here or there. All of these almost random occurrences that could have had all of these other consequences are very difficult and heavy to sit with. So I sit with them, because I don’t know what else to do, other than talk about it from time to time.

We’re post-October-7, but we’re not post-genocidal-violence-in-Gaza. That is shaping the types of conversations that people are—or are not—ready to have.

DK: It’s good to articulate it the way you and Alexei have been articulating it. There are certain types of violence that certain forces want us to feel are normal; certain levels of death, certain types of structural violence don’t ever make it to the media, don’t ever make it to these discussions, because it always has been and it always will be. But it’s very modern, very new, all of this. Even 1948: very modern, very new. And not set in stone, like you said.

We’ve talked about before October 7, but let’s talk about October 7 itself, because there has been a lot of debate about it. I don’t want to get into the disinformation—that’s not that useful. But what happened on October 7? How do we categorize this kind of violence, that is different from other types of violence that have been used and have occurred? And maybe we can touch on the ethics of resistance.

AA: The atrocities committed on October 7—they are unequivocally atrocities, and it’s been embarrassing to watch part of the pro-Palestinian community try to deny the nature of that violence. But what happened on October 7 is way out on the end of the continuum of the tactical repertoires of resistance. It’s not something that I could ever stomach or support. But it is a product of the intransigence with which nonviolence and more palatable tactical repertoires have been met in recent years. That has taken legitimacy away especially from the left and has given a legitimacy, if only in the process of elimination—again, Kanafani: This is all that’s left to us, all that remains. It emerges from that, from a place of repression of nonviolent, more moderate tactics.

It was shocking—it’s not a shock in the sense that since more moderate tactics have been shot down, there was going to be something more extreme. But along that continuum there is sabotage; there is violence against military targets; there is violence even against political figures. Way out beyond that is violence against civilians, and then also violence of the kind that we witnessed on October 7: sexual assault and torture, decapitation.

DG: I don’t have a lot to add. I agree with Alexei’s analysis. Something we need to consider in understanding what happened on the seventh is that there were a lot of people involved. This also applies to looking at all the different forms of Israeli violence that are perpetual throughout this occupation, throughout the regime of apartheid. But on the side of what Hamas did on the seventh, we can try to understand the strategic, ethical, and moral calculations of people like [Yahya] Sinwar or Mohammed Deif, and all the leadership and media…but we can also try to understand why these mostly young men—sometimes teenagers—carried out these attacks, breached the barrier into Israel, descended upon villages and kibbutzim, carried out atrocities.

These are very different questions, to me. There are all sorts of people in the middle whose incentives you want to understand as well. But the most tragic part of it is the young men who actually carried out the physical atrocities in the end, trying to understand—as in any case—what kinds of conditions and perspective leads one to do something like that. As I said, we can apply these same questions to trying to understand why (also mostly young) IDF soldiers carry out atrocities against Palestinians, and continue to do so as we speak.

It’s something that I’ve gotten really mentally stuck on, and a question that many researchers and others besides me have tried to answer.

DK: There’s one set of questions, like you said, where it has to do with the political or the strategic, dealing with the decisionmakers; that’s a separate analysis than the individual political psychology of people who engage in militias or engage in rape as a tool of war, any of those kinds of tactics. As you mentioned, these is wide literature on this from other regions and other examples, and we need to be able to bridge both to understand.

I also wanted to bring up Tareq Baconi, who wrote Hamas Contained. He was interviewed by the New Yorker shortly after the October 7 attack, and he talked about how there is, as you mentioned Alexei, a continuum of tactics, some violent and some nonviolent, and within violence there is also a wide range of tactics. And he said this kind of sadistic violence is not inevitable. It has to be separated out from how Palestinians shouldn’t be expected to live under occupation. But sadistic violence is dependent on people’s agency. Azmi Bishara also wrote a long paper about ethics and resistance, and he talks about distinguishing between what can be seen as a legitimate thing to do versus a criminal act.

We need to keep these discussions in mind, but it’s also difficult to have these discussions because violence is ongoing. We haven’t gotten to the “day after.” When do you have these kinds of adjudications? Maybe this is not the time to do it. I fully understand why people get upset about discussing these ins and outs.

JA: The timing is always sensitive. I’m not saying it’s not worth asking. It’s just worth asking while also trying to answer. We’ll never get to a perfect answer, if that even exists, but as you said, we have had cases like October 7 before. The context isn’t the same, the actors aren’t the same, sure, but the acts have occurred in the past. So it is worth asking. If we are serious about the fact that we are opposed to these acts and we don’t want them to occur, studying them surely is one of the ways we can prevent them.

I’m being a bit naive in saying, The more information we have the better we can act, though in theory that should be the case. But I don’t know. It’s been two months now.

DG: This is all consistent with my thinking on it. To build on what Dana was saying, we’re at a point now where we’re post-October-7, but we’re not post-genocidal-violence-in-Gaza. That is shaping the types of conversations that people are—or are not—ready to have. There are some people who want this time to be all about an accounting of October 7, due to subjectivity, nationality, or for ethical or moral reasons. But then of course there’s an urgent need for us to bear witness to what’s going on in Gaza moment by moment and focus our intellectual and analytical energy on that.

At least for me personally, this is creating a lot of difficulties and tensions in discussions with various people.

AA: This is violence against civilians, but after the twentieth century massive violence against civilians became commonplace (if it wasn’t already). It’s amazing how little I’ve seen in the mainstream news discourse about Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Dresden. There’s never been atonement, or even a reckoning with that massive violence against civilians. You read a US history textbook and it’s dismissed—lesser of two evils! Land invasion of Japan would have led to more deaths! Sure. Hamas has its own consequentialist justifications as well.

I think of Kurt Vonnegut and Slaughterhouse V. The guy never recovered, his whole life, from what he witnessed. He watched the firebombing of Dresden. He said, “I’ve become unstuck in time. I’ve turned into a pillar of salt, like Lot’s wife, unable to look away from the burning city.”

So there’s all of that in the backdrop. You see it in social media threads, people reference these things. They say, We have to do to Gaza what we did in Dresden. We’re no more to be blamed than the Allies.

DG: The analogies that we’re seeing to Dresden and the campaigns in World War Two fighting against the Nazi regime are alarming to say the least.

The intent in the assault on Gaza is clearly eliminatory towards the Palestinian people. Absolutely no measures are being taken for civilian lives. They are under complete siege and facing threat of famine, starvation, dehydration, disease, and the inability to access medical care at all. On top of that they are being bombarded and targeted with aerial weaponry and ground force incursions.

DK: Let’s segue to what’s been happening since October 7 in the West Bank and Gaza. There’s also been a debate around that. I think it’s not controversial to say “war crimes.” That’s been pretty well evidenced. But there’s a debate: Is this ethnic cleansing? Is this genocide? There was the New York Times article by Omer Bartov and the Jewish Currents article by Raz Segal.

So describe what’s happening in the West Bank versus what’s happening in Gaza, and how should we view this debate?

DG: I can provide some initial thoughts. I’m not an expert on international law or the definitions of these concepts. But genocide as it’s defined in the original Genocide Convention, as about the intent to destroy groups based on racial, ethnic, or religious grounds, is problematic for a number of reasons that scholars have pointed out. First, you have to demonstrate intent, and demonstrate that the intent is to destroy that group, as a whole or in part. Of course the loophole that all states and all actors accused of genocide are going to use is that It’s not our intent to destroy the group. Our intent is to fight terrorism. Our intent is to engage in self-defense against a militant actor within this group.

How do you measure or analyze intent? Well, we have these public statements from Israeli military figures and members of the cabinet, including the secretary of defense, that people are using as evidence of that intent.

I’m so much more concerned with the actual events and outcomes on the ground. From an international legal perspective it’s going to be important to pursue claims of genocide, of war crimes, and of crimes against humanity. But for now, in the public discourse, the people commenting on this are not exclusively those who will be bringing these claims to international courts. For all of us, the intent in the assault on Gaza is clearly eliminatory towards the Palestinian people. Absolutely no measures are being taken for civilian lives. They are under complete siege and facing threat of famine, starvation, dehydration, disease, and the inability to access medical care at all. On top of that they are being bombarded and targeted with aerial weaponry and ground force incursions in areas that are supposed to be “safer.”

There’s no question that it’s eliminatory towards Palestinian civilians. To me it’s observationally equivalent to genocide.

JA: About a decade ago, in 2013 or 2014, the United Nations declared that the Syrian regime’s actions in Syria amounted to “the crime of extermination.” Because of legal nuances, they couldn’t say genocide. There are also arguments that it is genocide, because Assad differentiated between “useful Syria” and the rest of Syria.

But there are terms used by Israeli government officials and the IDF—and not even just since October 7. I remember in 2014 Ayelet Shaked talking about “snakes.” Palestinian women are harboring snakes in their wombs. That’s genocidal language 101. There’s no other way of describing this. One of the IDF generals used the term “human animals,” and “forces of darkness.” I’m not saying there shouldn’t be a debate, but if it’s supposed to be about intent, the intent has been there; the intent has been expressed. On Al Jazeera, the ex-foreign minister said, They should all go to Sinai. These things are not hidden.

In parallel to this argument that I’m making, we just found out that Refaat Alareer was murdered—Palestinian academic, founder of We Are Not Numbers, editor of Gaza Writes Back; folks in this space know him or know of him—and six other family members were killed. I listened to his interview on Popular Front about a month ago, and referenced it on this podcast because it was such a difficult one to listen to. You could hear the bombs all around, and the kids in the background yelling. Just a horrible thing to listen to. I would recommend it anyway, to folks who feel they can stomach this. He says a lot, in addition to it being very difficult.

What I’m saying is that Refaat, as a civilian, was murdered. Whether he was murdered in something that we can call genocide or something we can call a war crime doesn’t matter as much. The fact that it does matter has done more of a disservice to humanity than otherwise. I’m not saying distinctions don’t matter at all. But the act of a crime against humanity or a war crime has almost been deflated unless you can call it genocide. Genocide is the top thing, and everything else follows. If your entire family is killed and it’s not “technically” genocide, does that really matter?

For me, it doesn’t really. There should be accountability nonetheless—I’m not saying we disagree on that, on this panel. But as far as the discourse more broadly, there does seem to be a hierarchy of crimes, when the end result is the same.

DG: I think that’s absolutely right. The murder of Refaat—Refaat was a poet—and the targeting and destruction of historical archives in Gaza, the complete destruction of Gaza City’s municipal archives, are forms of intent to destroy a group through cultural and historical elimination.

AA: So many thoughts about all of that. This climate of contempt for knowledge, for books, for archives, for poets—this is the core of fascism. Fascism often ends up being antisemitic, but it’s not a core quality to it. Eric Hobsbawm doesn’t think so in Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century. Rather it’s anti-enlightenment, anti-knowledge—and against the notion of humanity, against the notion that we’re all somehow in this together.

I didn’t expect to ask this before this conversation, but this question just emerged for me: What does it mean to resist a government or authorities that are willing to use annihilative violence? In a lot of the academic literature on insurgency and rebellion and resistance, there’s an understanding that the rebels, the militants, live embedded in the civilian population, and that it comes down to a matter of information: can the government convince the population to snitch on the militants? Of course, they can’t unless they win over their “hearts and minds.” The hope is, they win over hearts and minds by undoing the systems of oppression that gave rise to the militancy in the first place.

You see even American military commentators trying to intercede on what’s going on in Gaza now, and saying, Yeah, but you need to win over the civilian population, and if you just keep bombing them it will just create a new generation of militants! And I’ve said many times: there is no military solution, we can only get somewhere through a political process. But when I say it, I have to admit there’s a bit of a tremble in my voice. Because with an annihilative government that’s willing to wipe out or totally displace an entire population, maybe there is a military solution. Maybe you can just murder everyone and destroy all the archives, and there will just be silence after that.

DK: It’s basically what Bashar al-Assad did in Syria. For the Syrians that he no longer wanted to be a part of Syria, the solution was a military one: to annihilate them and displace them. Complete destruction.

We’re talking about the annihilative government on the Israeli side, and then there are some people who suggest also that Hamas has a zero-sum understanding of the conflict. These are different kinds of actors. But if it’s zero sum, and the military option is the only thing being discussed, whether it’s on the government side or the non-state actor side, what responsibility does the international community have to this kind of situation?

I’m pretty sure the first step is not to continue fueling it. Given that these are the structures we’re dealing with, let’s not give them the space to engage in this level of military strategies or “solutions” to their issues.

Even if US policymakers don’t share annihilationist intent towards Palestinians, we are supplying the immediate arms and weapons to carry it out. Maybe the US’s influence cannot change the annihilationist intent within the halls of Israeli government, but the more urgent need is to deprive them of the tools to carry it out.

JA: Israel-Palestine as a conflict has the most international dimensions perhaps of any conflict. We know for a fact that Israel cannot do what it’s doing without American support. That’s just a fact. It can do a lot of damage without American support, but American support is clearly very crucial. The Americans send them weapons that they don’t send to any other allies. That’s not nothing. And obviously there’s the money sent every year (and they recently unlocked even more money).

I’m not convinced that the Americans can’t stop this the second they want to. I’m pretty convinced otherwise: that they can put a red line. It’s different than the “red line” Obama put in Syria, because Bashar al-Assad was never an ally of Obama. This is different. This is direct complicity. Nothing that’s happening right now in Gaza would be even remotely possible if the Americans decided overnight, You know what? That’s it. I have difficulty imagining what the Israelis could do about it, to be honest.

DK: We have histories to suggest. We know that Reagan put a red line on Israel’s conduct in Lebanon and prevented certain things. I’m not suggesting it’s a push of a button. But as far as the conflict becoming internationalized, some parties are more responsible than others, and some parties have more leverage than others. There is a precedent in American foreign policy for creating these kinds of lines, and the level of demands we should have for an actor like the United States, that has so much leverage, should be similar to the parties that provide space for the political leadership of Hamas, for example.

There should be more pressure to try to de-escalate this as quickly as possible. The medium- to long-term political negotiation is a related but somewhat separate matter from ending the immediate violence.

DG: I was thinking about Alexei’s question about resistance to annihilationist state violence. All of what you, Joey and Dana, are suggesting about the US’s role here is critical, because even if the Biden administration or US policymakers don’t share the annihilationist intent towards Palestinians, we are supplying the immediate arms and weapons to carry it out. Maybe the US’s influence or leverage is not in a position to change the annihilationist intent within the halls of Israeli government, but the more urgent need is to deprive them of the tools to carry it out.

On Hamas’s side—of course Israel is now using the justification that it appears Hamas has annihilationist intent towards Jewish Israelis as well, because of what happened on October 7. But October 7 has come and past, and they’re still launching rockets occasionally, sure, but we’re in Iron Dome world, so we’re not seeing Hamas carrying out what I would call annihilationist violence at this moment.

DK: In the Global North, where we’re all based, we do not have the ability to limit Hamas’s conduct anyway. There are actors who have that ability. We can discuss what the Qataris should do, or what the Iranians should stop doing. But we aren’t in that position. For the immediate-term goal of de-escalating: whether or not you accept that one or both parties has annihilationist or zero-sum views of the conflict, what we’re seeing unfolding has to stop first.

I do think the United States has the leverage, even in the medium to long term. I don’t think they can switch Israeli leadership, or switch Israeli public opinion. But you exacerbate certain trends if you provide cover for extreme rightwing people, and you make sure the international community can never respond to certain kinds of behaviors. In the medium- to long term the US does have leverage over what kind of leadership can be seen as acceptable and what kind of leadership emerges in these places.

Sorry, I know we need to wrap up. Could we have a takeaway for the episode from both of you about what people should understand about violence in Israel and Palestine?

AA: It’s a failing of human nature that our attention is drawn to events we forget about non-events, things that fail to happen. The Israeli psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman calls it the WYSIATI principle: What you see is all there is. It’s a human bias that we all struggle with. So my challenge to myself and all of us, all the listeners, is to look beyond the events: October 7, or the kinetic violence that’s followed it. Look beyond that to the non-events, to the absences. Pull up a chair for the ghosts, and try to register some compassion for what people live with and live without when they are living under structural violence and systems of oppression.

DK: That’s really beautifully said. It made me think about not just pulling up a chair for the ghosts and thinking about the losses, and the counterfactuals and the non-events, but also being more future-minded, thinking about possible alternatives that could become less likely as a result of the dynamics that we’re seeing unfold—but maintaining a space to think about alternative futures as well.

DG: Recently I have been trying to think through some of those empirical futures. Right now any conversation about the “day after” is fraught, in Gaza or in Palestine and Israel as a whole, but I find myself compelled—and maybe others feel the same way—to have those conversations. Because obviously the continuation of this war on Gaza is taking place in a context in which the Israeli government is being faced with very little pressure to discuss that.

What are Palestinians, and what is Palestine, supposed to look like after all of this? I’ve been trying to think about what the expected use of coercion is supposed to look like in Palestine after seventy-plus years of Palestinians never having any control over the agents of coercion and violence in their homeland.There are questions in the discourse: Is there going to be a rejuvenated Palestinian Authority? Is there going to be some kind of international transitional administration? Is Israel going to reassert direct rule over Gaza? But the glaring absence in all of this, even considering those who are waving their hands towards the “two-state solution” (and this has been the case for decades in US policy), is that Palestinians are not allowed to wield coercion. That’s the baseline assumption of all of these models.

The more liberal Zionist crowd will say Well, they can build towards that,or, Palestinians will initially be demilitarized but then there will be some transitional process…I just find myself incredibly frustrated with these discussions. Because of October 7, some people are not ready, or psychologically capable, of talking about Palestinians wielding the ability to defend themselves and their communities. What does that look like? We can’t talk about this future.

DK: It’s an element of sovereignty. All of these discussions are had without thinking about or taking seriously Palestinian claims to sovereignty. They are trying to replace that discussion with Palestinians’ claims to self-governance, or something less-than. Even if you agree with the premise that Palestinians should not have full sovereignty—let’s assume that’s a starting point—strategically it does not work, because the Palestinian public will reject any such arrangement.

That’s another glaring omission in all of these discussions. Where is the Palestinian public in any of this? It’s the hand-picked people that the Americans want. They want the PA to come back to Gaza. Nobody is considering what Palestinians actually want! I was asked this question once: If not the Palestinian Authority, then who? There’s a vacuum of leadership. You think Palestinians have this vibrant society and there’s nobody who has any ideas or any leadership who could possibly come forward in this moment? It’s so ludicrous.

JA: There have been hostages released, and continue to be released, so we do know that something is possible; some compromises are politically feasible. The question that the Netanyahus of the world and their supporters don’t want to ask is Why didn’t they do that before? Why wasn’t there a deal beforehand? Clearly a deal was possible. I’m sure it did not require rocket science. What Hamas was asking for was the release of Palestinian prisoners (I call them prisoners and not hostages because it’s a state doing that, but they’re effectively hostages with no rights whatsoever). What the Israelis could have said was Okay, fair enough. But they were not in the mindset for that.

Is international law supposed to be whatever the mindset of the powerful is on that specific day? If that’s the case, by definition there’s no international law. By definition there are no human rights, there is no such thing as no one being above the law. Because clearly Netanyahu is.

Whenever something like this happens, there is a tendency among the wider commentariat—writers, journalists, policymakers—to want to see how this affects only Israel-Palestine, how it will affect Israelis and Palestinians. And this makes sense, but it also obfuscates that this has happened in the past in different places and in different ways. The echoes are never perfect. But what happened in Syria and what the Assad regime was able to get away with also rewrote the rules. What China gets away with in Xinjiang as well. In many different places, in many different contexts, it creates different rules of the game that get further and further away from what it should be.

DK: Thank you guys so much for having this discussion and being on the podcast. I hope you take care of yourselves as we consume all of this violence and destruction.