Featured image: Meeting of an agriculture cooperative in Rubariya, near Dêrik.

AntiNote: In light of the ongoingly escalated project of death and destruction that tyrants and oligarchs the world over are embarking on, we are humbled to transmit a report from the plains of Western Kurdistan as a beacon of resistance, an example to follow, and a cause among many others to which we can extend our solidarity. This report resonates deeply with other communities around the world who are courageously resisting similar processes of colonial and imperial genocide and ecocide. We extend our gratitude and solidarity to the people of Koçerata for their refusal to give up fighting with forces of life, for their refusal to give up their relationship with their ancestral homelands, for experimenting and remembering and continuing on with their traditional ways, all while under fire from some of the world’s most brutal war machines.

“We will defend this life, we will resist on this land”

by the Committee of the Make Rojava Green Again campaign

29 March 2024

For years, the Turkish state has been killing civilians and political representatives in Northeast Syria, in addition to carrying out an ecocide in the region and bombing basic civic infrastructure, all of which has gone relatively unnoticed by the international public. Even in the face of these attacks, the population is resisting, defending their right to live on their land and the system of self-administration they built up at the beginning of the revolution.

Kurdistan was divided into four parts during the colonial division of the Middle East and the subsequent creation of nation-states that happened throughout the earlier part of the twentieth century. With this territorial division, the Kurdish people were separated between Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. Rojava, meaning West in Kurdish, is the Syrian part of Kurdistan, named for its location as the western part of Kurdistan.

The history of Kurdistan, the ecological way of life of the people, the effects of the attacks, and the methods of resistance are intrinsically related. In order to make them more understandable, we will focus on the area of Koçerata. Koçerata and the people living there carry a heritage of hundreds of years of communal life, depending on and coexisting with the nature and the land, in a way that has set strong foundations for social-ecological life in the region.

Social ecology refers to the idea that a free, ecological, and democratic life is only possible when the relationship between society and ecosystems are harmonious and free from domination. Throughout history, different systems of domination have imposed upon their people a worldview that separates “subject” from “object”. All forms of oppression, such as patriarchy and ecological exploitation, have developed from this separation. Thinking of our society and communities as ecosystems instead allows us to understand that self-organization, connection with the land, co-existence of different identities, self-defense, and sustainable use of resources according to needs and in balance with the environment are all essential elements of a free life. While large parts of the population have been distanced from this reality by the capitalist mentality and lifestyle, in some regions like Koçerata, people are resisting in order to carry on a social-ecological way of life.

From 6 October 2023 to 15 January 2024, the region and its people have been subjected to airstrikes carried out by the Turkish army. Koçerata’s rich and pioneering heritage is under massive attack, but still, the people do not consider giving up their way of living or leaving their land.

Koçerata: “Land of the Nomads”

Koçerata, the “Land of the Nomads,” lies between the heights of Mount Cudî in today’s Turkey, the Şengal mountains in today’s Iraq, and the stream of the Tigris river. If one stands on top of the mountain Qereçox and looks down from there, the whole plain in its full beauty unfolds in front of ones eyes.

View of the Koçerata region from the Qereçox mountain.

For hundreds of years, this region has been home to nomadic and half-nomadic tribes, Kurdish as well as Arab, living and working together. While Arab tribes would move around in the plains, the Kurdish half-nomads (Koçer, in Kurdish) would stay in the plains for the winter, moving with their herds of sheep and goats to the highlands in the North during the summer. The people lived like this until 1925, when nation-state borders were drawn in the Middle East. This deeply impacted the lives of the half-nomads, cutting them off from the highlands. The Turkish state pursued a politics of homogenization and genocide, while the French occupation and the Syrian state also severely attacked the natural way of life of the people.

Unwilling to give up on their ancestors’ way of life, a lot of the people of Koçerata continued living in tents and moving around the plains until 1945. Zehra Ali, who organized in one of two Peoples’ Councils of the region, still remembers this time: “Until I was 15, every weekend, when we would not have to go to school, we were going with buses and pickups to visit our parents who were staying with the herds. It was the most beautiful life; we were really sad when we had to go back to school.”

The Syrian state wanted to create a society that lived according to the habits of modernism, rather than carrying on their heritage. The state imposed a monoculture economy on the people, only allowing people who were loyal to the regime to work. The people were not allowed to grow and harvest food to sustain their own life. As was the case in all of Rojava, this forced more and more people from the region of Koçerata to leave their villages for the bigger cities. Upon arriving in the cities, people who had previously lived independently off of their own efforts on their land had no choice but to sell their labor for the lowest wages imaginable. Koçerata was also exploited for its rich oil deposits. One of the biggest power plants of Northeast Syria was also based here, in Siwedî. Built in 1983 by a French company, it was one of the main gas and power stations in all of Northeast Syria, serving between 4 and 5 million people, until the attacks this winter.

This economic colonization was also an attempt to destroy the hundreds of years of social-ecological life in the region, setting out to completely erase all markers of Kurdish identity, and with that, laying a foundation for the exploitation of humans and nature in its entirety. In the second part of the last century, the Syrian regime imposed a wave of industrialization and urbanization on the people, continuing the process of undermining the lifestyle of the Koçer, and tearing the people of Koçerata away from their land.

New life grows from an old heritage

The people of Koçerata have been part of the liberation struggle in Kurdistan and the Rojava revolution since the beginning. Many of the local youth who went to fight against ISIS are now taking on responsibilities within Rojava’s self-administration structures. After the Syrian state was expelled from the region and the autonomous administration was established, many families returned from the cities to build up their lives in their own villages again.

Rûken Şêxo, spokesperson of the People’s Council in the village of Girê Sor describes the life of the people and the creation of social-ecology in the region: “The life of the Koçer is very simple and beautiful. We don’t need a lot from the outside. At every house you will find a small garden, where the families are growing vegetables, herbs, and plants, for example tomatoes, onion, salad. Some will also raise cows, chicken, and turkeys. We make things ourselves, especially yogurt, cheese, and milk. From our childhood onward we learned to create everything by ourselves, from the things we have. This is also what we are going to teach to our children.”

Turkey’s war against Rojava: an attack on the development of social-ecology

For thirteen years now, the people of Northeast Syria have been building infrastructure, organizing, and developing social ecology, all while facing threats and attacks, primarily by the Turkish State, in an ongoing attempt to strip the people of their hard-earned autonomy and self-governance.

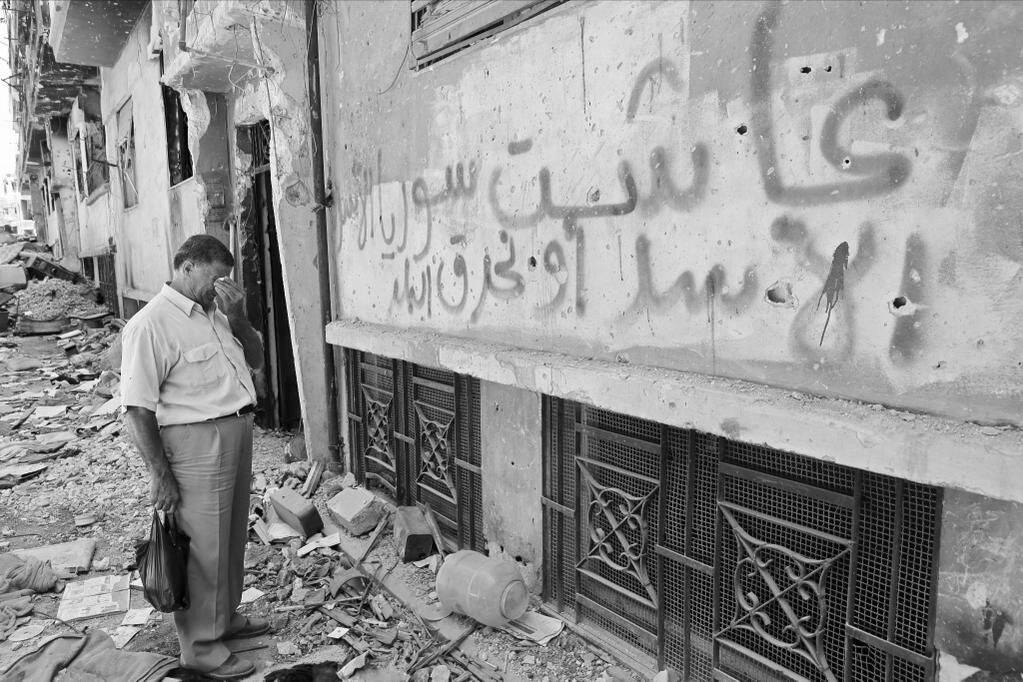

In November 2022, heavy attacks were executed at an alarming scale, targeting infrastructure for basic life needs like water and electricity; still, the most recent bombardments, from 6 October 2023 to 15 January 2024, mark the worst escalation since 2019. In this period, the Turkish army used drones and fighter jets to carry out over 650 air strikes, hitting over 250 sites, many of which were targeted several times. Throughout this massive operation, fifty-six people were killed, two of whom were children aged ten to eleven, while at least seventy-five people have been injured. Among them were workers killed at their work sites or collecting cotton in the fields. The airstrikes targeted essential infrastructure: eighteen water stations, seventeen electricity plants, schools, hospitals, factories, industrial sites, agricultural and food production facilities, storage centers for oil, cooking gas, grain, and construction materials, medical facilities, and villages.

The main targets of this airstrike campaign have been the electricity, gas, and water infrastructure of the region. The purpose is clearly to destroy the basis of people’s livelihoods. The war on infrastructure is a war on the people. Aside from the physical destruction, these attacks aim to harm this society’s psychological status and to destabilize the region, in order to stop the democratic process that is going on within the Autonomous Administration by any means possible.

Koçerata became a central target due to the important infrastructural sites in the region, which are essential for the production of electricity, cooking gas, and petrol. Being mainly a rural and agriculture-based region, the relationship between war and social-ecology here is very clear.

The electrical situation was already drastically impacted, as Turkey has increasingly cut off the water flow coming into Rojava since the beginning of the revolution. The rivers used to be the main source of electricity for the region, but in the last few years, the Administration was forced to move back to using fossil-fuel based energy sources in order to secure people’s basic needs, such as heat, cooking gas, and some hours of electricity.

One of the most critical infrastructural targets was the electricity plant of Siwedî. “Being the main gas and power station for all of Northeast Syria, when there are problems within the plant, it affects the whole region,” explains Rûken Şexo. “After that shelling, four to five million people have been affected.”

Destroyed tubes and petrol lines in Siwedî.

In the Cizîrê region, where 50% of household electricity comes from the Siwedî plant, two million residents have been left without municipal services, electricity, power, and water. In January, the Turkish army carried out such heavy airstrikes on the station that the plant has been almost completely destroyed, with only 10% of the plant remaining intact. This makes it impossible to even consider a normal process of repairing what has been bombed.

Shellings on Koçerata

“The shellings are hurting the people of Koçerata, in all aspects of life” explained Xoşnav Hesen of the village Girê Kendal. “These are from the attacks—” he showed us the deep cracks on the walls of his house. “Many places around our village were bombed. A barn was also targeted, killing 200 sheep. We have been many days without electricity and water.” The villages are mainly connected to the general electricity line, and the loss of electricity is heavily impacting all aspects of life, including villagers’ access to water. Without electricity, the water pumps do not work, meaning the water can’t be extracted from the wells and distributed to the villages.

While a lack of access to water is generally a problem for supporting human life, this is especially crucial in the Koçerata region given the agriculture-based life of the people. The water situation was already very strained because of how Turkey has been cutting off the supply. What was once called the fertile crescent, crossed by the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, has now been experiencing heavy droughts over the last few years. The river flow that was allowed to cross into Rojava decreased by 42%, with peak days hitting 80% reduction, which of course affects all aspects of life: drinking, hygiene and health, agriculture and food production, animal life, the economy, education and gender dynamics. Additionally, the Turkish state has altered the water quality, releasing contaminating sewage residue into what little water still flows into Northeast Syria.

“Most of the people live from the products of the earth and from the animals that they raise themselves,” Rûken Şexo explained. “Without water, the plants are dying and the animals cannot drink. The cultures are affected, the animal life is affected. The basis of people’s economy, of families’ economy in the region depends on [access to water]. Now families are having economic problems, because they used a lot of money to plant and now everything is gone, the animals are dying because of the lack of water.”

These military operations aim to create fear and frustration. Delal Şêxo, from the village of Hamza Beg, explains that “creating, or building up [infrastructure], is not the problem—the problem is war. You work so hard, create so much, invest so many resources, and then, in one second, it gets destroyed.”

“We don’t leave our land, we organize ourselves” – Resistance of the people on their land

Ecological factors were among the primary causes contributing to the onset of the current war in Syria. Droughts and oppressive regime policies alike resulted in a mass exodus to urban centers, limited access to basic needs, and various humanitarian crises, all of which led to the 2011 uprisings. During the subsequent war, numerous crimes against humanity and ecology were committed, such as the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian and Turkish regimes, and the scorched-earth strategy employed by ISIS during its retreats (i.e. poisoning water sources and destroying oil infrastructure and chemical factories). The current attacks led by the Turkish State must be understood in this broader context of war and ecology.

Aside from the direct ecological consequences of the water dams, logging, and the destruction of oil infrastructure, there are also indirect ecological consequences that hinder the progress of the Revolution. The systematic destruction of basic infrastructure forced the administration and the whole economy of Northeast Syria to devote themselves toward the continuous work of reparation and rebuilding, ushering in high costs in terms of both human and financial resources. This warfare impedes the development of agro-ecology and eco-industry, which the Autonomous Administration holds as essential worldviews to cultivate and promote.

The paradigm of the Rojava revolution aims to foster the development of a society based on grassroots democracy, women’s liberation, and social-ecology. In this framework, ecological sustainability, self-sufficiency, local production and consumption, and decentralization are crucial. However, the decentralization of certain infrastructures faces challenges not only due to the attacks but also due to the embargo. The construction of smaller, decentralized infrastructures—such as electricity production—is in the works, but some necessary materials are still unavailable and cannot be transported across borders. The unavailability of certain materials adds further difficulties to the maintenance of existing structures and leads to an increasing dependence on oil. Even in the case of building new infrastructure, it would still face the threat of destruction. Essentially, this aggression attempts to eliminate the still-present experiences of social-ecological life, and to obstruct the emergence of a social and ecological revolution, in order to perpetuate the capitalist system—despite its inevitable collapse due to environmental factors.

Our social institutions have to draw emergency plans during and after each wave of attacks, which compromises our capacity to work on long-term projects. Larger scale development plans are perpetually on hold for projects like widely distributed organic fertilizers, or sourcing different means of energy production—like solar, biogas from animal manure and organic wastes, and wind energy—because of the resource limitations and the constant necessity to respond to emergencies and the immediate consequences of war.

As ideological and practical resistance, the Revolution draws inspiration from the wisdom of natural society and adapts to its current context. In spite of the aggression of capitalist modernity, our decentralized and ecological economy takes example from the sustainable aspects of the traditional way of life in the region. Throughout the contexts of forced settlement, remapping of the region, and environmental changes imposed by hegemonic powers for centuries, the people of Koçerata continue to develop their solutions in line with their values and cultural heritage. Aligned with their will to stay on their land, they conserved ecological and sustainable practices through their agriculture and shepherding as well as through the sharing of resources.

In the whole region of Northeast Syria, direct and indirect attacks to the countryside and agriculture fields compromise not only activities related to food production but also the people’s attempts to recover the original quality of the soil, impoverished after years of regime-imposed intensive monoculture practices. The transition to sustainable, traditional methods of agriculture and agro-ecology is motivated by the desire to recover techniques from the past, but also because of how fully it reflects the principles of richness in diversity and resilience, in communities as well as in ecosystems.

Shepherd with his sheep in Koçerata.

Connection with the land and the re-establishment of a balanced relationship with nature is also fertile ground for the development of democratic relations and structures. Staying on ones land and organizing life communally is a way to defend one’s identity and traditions, which strengthens the culture of resistance in this community. The Turkish state’s attempts to make the people flee intends to physically empty the land, as well as to interrupt the transmission of culture and knowledge, like that of agricultural practices, for example—traditional methods, seasonal changes, local plants—in addition to every other aspect of life in the region.

The Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria encourages the establishment of cooperatives, agro-ecology, like the production of organic fertilizers, and eco-industries based on the cooperative system and on a circular approach to production and consumption. In a centralized economic system, numerous localities depend on a single piece of infrastructure. Military attacks can therefore paralyze the society by targeting a few key areas. Decentralization, however, could reduce the effectiveness of this warfare. A single attack would affect just a part of the whole infrastructural network and the impact could be balanced by the operational continuity of other decentralized sites. Additionally, a decentralized system implies smaller and simpler infrastructures that can be more easily maintained. Furthermore, better self-sufficiency would help withstand embargo policies, ensuring logistical support for civilians and military structures for the continuation of social life and self-defense.

Local social and economic autonomy fosters the ability for people to organize their own forces. Despite difficulties and threats, the people are showing a strong sense of solidarity amongst one another, determination to stay on their land, and they are developing ways to collectively withstand the hardships they are facing. The municipality visits the different Communes to inform them, share evaluations about the situation, listen to their needs, try to find solutions together, and collectively organize the whole society, making everyone take responsibility for the collective. The people of Koçerata pool their resources in times of difficulty. Neighbors share generators and water pumps during electricity shortages. Some villages deliberately limit their electricity for hours to support others. Certain families combine financial resources to afford a communal water pump system independent from electricity.

During the attacks of October 2023, the five hundred workers of the Siwedî plant repaired and maintained the infrastructure to restore electricity to the people, despite the airstrikes and the fear of being targeted again. Various strategies have been devised to safeguard both people and their lands from the attacks. During the airstrikes in late December, the Koçerata community mobilized to create human barriers around the Siwedî power plant. For several days, crowds congregated around the power plant, aiming to shield it from airstrikes.

Human shield demonstration at the gas power station in Girê Siro, near Dêrik.

Later on, in January, even in the ruins of Siwedî, the high spirits of the community couldn’t be defeated. This brought about a time of new initiatives. In each village, residents began pooling funds to support the installation of local generators. The priority was to set up an emergency plan, but as for their long-term strategy of social-ecology, the solution-making power is already there: initiative from the base, self-organization, and decentralization.

The foundation of ecological resistance lies in the connection between the people and the land. The land is home; it needs to be protected from aggression and it must be taken care of in order to ensure the continuitation of life. While a lot of attempts have been made to alienate and displace the people of Koçerata, most of them have made the decision to stay on their lands. This determination to resist and build local autonomy forms the roots of both self-defense and ecological practices.

Resistance and autonomy go hand-in-hand with ecological consciousness. These frameworks of social-ecological models, self-sustainability, and decentralization have strong potential to constitute a solution for a lasting peace in the region. Likewise, the reality of Koçerata is a meaningful and inspiring example for these frameworks, not just of theory, but of practice, of resistance and self-organization. Resisting the current centralized, urbanized, and monoculture global systems, Koçerata continues to show us an alternative path, via sustainable ways of living, working, and producing.

Make Rojava Green Again is an ecological campaign working in Northeast Syria/Rojava, in cooperation with the democratic self-administration, building practical ecological projects and ecological popular education. As part of the Internationalist Commune of Rojava, we work to contribute to the ecological revolution in the region. We work together with social organizations and institutions on projects for the development of renewable energy, such as the installation of solar panels. We also help through material support and knowledge-sharing between activists, scientists, and experts with committees and structures in Rojava, developing a long-term perspective for an ecological society. We publish reports and analysis on the ecological situation of Northeast Syria and build connections with ecological struggles worldwide.

Access the full report from which this text was consolidated here. Featured image and all subsequent images were provided by MRGA and feature in the extended report.

Edited lightly for readability and clarity by Antidote Zine. Printed with permission.