AntiNote: On the eleventh anniversary of Assad’s chemical massacre in Ghouta, we present an archive interview on the topic, transcribed from the 11 April 2020 episode of The Fire These Times podcast and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole conversation:

Chemical attacks have a psychological effect to a much greater extent than other weapons, even though all weapons kill and injure. This is why the chemical attacks in Syria reawakened so many nightmares for Iraqi Kurds. You never really get those images, or that experience, or those stories out of your head.

Elia J. Ayoub: This is a conversation with Sabrîna Azad. She published a moving piece for Mangal Media entitled “From Halabja to Ghouta” in which she looked at how deniers of Assad’s war crimes in Syria were evoking painful memories for survivors of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal campaigns against Kurds. She spoke about the legacy of the Halabja massacre, part of the Anfal genocide of the late eighties, as well as the 1991 uprisings against Saddam, and why they offer better insight into the world’s reaction to Syria since 2011 than the more frequently mentioned 2003 invasion of Iraq does.

Sabrîna Azad: I’m Sabrîna. I study toxicology and the histories of mountain regions in the east. I also do data analysis and visualization behind a wide assortment of things: refugee rights, war crimes, and especially anti-authoritarian movements, with a focus on Kurdish issues. Thank you so much for having me today.

EA: The topic of our conversation is a rather heavy one. Your piece is about two of the most notorious war crimes in modern Middle Eastern history, which is saying quite a lot. Can you give us some background on this piece and tell us about why you felt the need to write it?

SA: They are two of the biggest war crimes in the region, and there are a lot of articles on them out there—but they’re mostly from a geopolitical lens: some deny the chemical attacks and take Russia’s stance; even the ones that affirm them will talk about the need to assert American supremacy over Russia. That’s really not what the uprisings were about—it’s not even what the victims want. I saw people thinking they were being clever by bringing up Halabja to explain why nothing should be done about what the Assad regime is doing today.

I thought, Who better to consult than the actual victims of Saddam’s chemical attacks? It’s their tragedies that are being used as a political toy so many years later. All we hear is what white people in the West think about Syria and what should be done there. My view, as someone from the Global South, has usually been that wrongful inaction like enabling a dictator in the past doesn’t mean that there should be inaction and enabling for the rest of all eternity. That doesn’t make any sense, especially when it comes to something as monumental as chemical attacks.

I’ll get into more a little later about why they are so important. But as I listened to older survivors from Kurdish and Iranian communities, I realized that most very strongly supported strikes on the regime after its chemical attacks—or at least some form of enforcing the “red line” that Obama had mentioned but never actually enforced. I couldn’t find any article that really focused on what these people—the people who had actually been through this exact situation before—were saying was the best course of action. And there was really nothing out there about the solidarity between the victims from different countries. It was really important to highlight this, because we don’t get a lot of that.

There’s so much sectarian and racist propaganda coming from our region that we really need to highlight when we do see genuine grassroots solidarity, every opportunity we get. There were people in Rojhalat, the part of Kurdistan under Iranian military rule, who went out in the streets and carried posters in solidarity with Syrian victims. It wasn’t thousands and thousands, but it was still a sizable number. There was no media attention on this at all; I only knew this because I know people from there.

I wanted to honor the anniversary of the Halabja massacre by amplifying these arguments which are so overlooked. But also, personal narratives are really crucial to remind people that these are human beings’ stories, and not pawns in a geopolitical chess game, which is how a lot of people view this whole thing. Which is why they’ll be like, What about Halabja? Nobody did anything there, so why should they do anything about what the Assad regime is doing now?

EA: Can you tell us a bit about the Halabja chemical attack?

SA: The Halabja chemical attack was the culmination of the Anfal genocide—some people put its start date in 1986, some people put it in 1988 at the height of the campaign. But the genocide itself was an event within an event, which was the Iran-Iraq war. I don’t think people realize how much that war impacts politics in the region still to this day. It consolidated the revolution in Iran; it allowed Khomeini to maintain power, because when you’re being invaded by another country people rally around whichever leader is most potent at the time. A lot of different factions in the Iranian revolution were slammed out once Saddam invaded.

When Saddam invaded Iran, Iraqi-Kurdish forces aligned with Iran because they saw it as an opportunity to get rid of this regime. To punish them for this, Saddam took it out on Kurdish civilians, as dictators do. It started as rounding up young Kurdish men and executing them—the rate of this was so high that this (and the genocide in Bosnia) gave rise to the term gendercide: when not only a specific ethnicity or religion is targeted but also specifically young men. It was really monumental in those terms.

Halabja was a culmination of all of this. That town was at the time under Iranian military occupation. There’s footage of an Iranian soldier, right after the Halabja attack happened, saying, We understand why Saddam attacked Iranian soldiers with chemical weapons—we’re his enemy—but how can you attack your own people? This plays into the genocidal ideology that the Saddam regime had—this was a logical culmination, but the manner in which it was done was very shocking to the world.

EA: You can never compare two massacres, but we saw relevant echoes in Ghouta, especially in the lack of response. Quite a lot of my political and personal development has been defined by the Ghouta chemical attack. For those who don’t know, Ghouta is a region in Syria, and the chemical attack happened on 21 August 2013. To this day it’s still one of the worst war crimes committed in Syria. Again, that’s saying quite a lot.

The thing about the Ghouta chemical attack is that in addition to the geopolitical consequences and the real-life consequences for the victims, it also became a talking point. It was happening before as well, but Ghouta 2013 was one of the starting points of a massive online disinformation war by the Russian government and its supporters (sometimes paid, sometimes not—some people do this for free!).

It’s become a cliché among many Middle Eastern activists that the only thing many so-called “anti-imperialists” in the West know about the region, if it’s not Israel-Palestine-related, is the 2003 imperialist invasion of Iraq. They may have some limited knowledge of the 2011 uprisings, especially in their early days—but it died out relatively quickly, towards the end of 2011, and indifference came back.

Whenever we mention the need for something, anything, to be done about Assad’s now nine-years-long extermination campaign (crime of extermination was the term used by the UN because they couldn’t legally use the word genocide), we often get people who say, What about 2003? What about weapons of mass destruction? Last time the mainstream media said the same thing! And besides the racist assumption that nothing of significance happened in almost two decades, as though Iraqis, let alone Syrians, were just doing nothing for the past two decades, the irony here is that Saddam did in fact use weapons of mass destruction.

You go back to the context of the 1991 uprisings in Iraq, in Kurdistan. Can you tell us a bit about these uprisings? And in addition to giving an overview, what are some similarities that you see between these uprisings and the ones we’ve been seeing since 2011?

SA: What most people in the West know about 1991 is that Saddam invaded Kuwait, and US coalition forces intervened to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait—and this is where their knowledge stops. But after the whole debacle in Kuwait, George Bush Sr. made an appeal on the radio, telling Iraqis that the way for them to end the violence and oppression by the Saddam regime would be for Iraqis themselves to remove Saddam. When he said this, what the US actually wanted was for Iraq to be ruled by a military regime but without Saddam. They weren’t concerned about democracy, of course. They wanted to get rid of Saddam because he was annoying to them.

Iraqis and Kurds answered this call very enthusiastically. I want to point out here that while they might have been “encouraged” by the West—I mean, they believed that If Saddam retaliates, which he will, then the West will support us—the thing that motivated them the most was their own grievances with the regime. These are people who had lost mothers, sisters, brothers, and fathers to this awful dictatorship. They didn’t need someone from the US to tell them, Go risk your life to get rid of Saddam. They would have done it, but they wanted reassurance.

There are mixed accounts of how it started. But one account is that an Iraqi soldier shot a portrait of Saddam, and this symbolic event snowballed into an uprising. Soldiers defected from the army, turned against the regime; a lot of Iraqi Shi’a dissidents who had been exiled to Iran returned—and they had been inspired by the 1979 revolution in Iran and wanted to turn Iraq into a similar Islamic republic. But they weren’t the only rebels by any means. This is important to point out: the armed rebellion was a very diverse movement. It included leftists, communists, Kurds, anti-Saddam Arab nationalists, all sorts of people. Similar to the Syrian uprising, there wasn’t just one ideology that motivated it.

The rebels were able to liberate the majority of the provinces; it wasn’t limited to a certain area like perhaps the 1982 Hama uprising in Syria was. One way that this 1991 uprising in Iraq was different from the Syrian revolution, though, is that the Syrian revolution started out as peaceful protests, whereas the 1991 uprising began as an armed rebellion—for several reasons. Saddam was much more openly war-mongering than the Assad regime, in terms of outright invading neighbors, so there was never really an opportunity to get normal protests going. This is why I hate when people use the term “stable” to describe any authoritarian regime, particularly Saddam’s. It makes it sound as if Iraq under Saddam was simply minding their own business, didn’t fight more than one war—not to mention Saddam’s rate of repression of dissidents.

Going back to the uprisings: the Shi’a majority south and the Kurdish north were liberated for a short time. This is when we’ll see a lot of parallels with the Syrian counter-revolution. Saddam’s forces responded with brutal violence. There is horrifying footage of women and children trapped in a shrine in Karbala begging for god to save them because Saddam’s military aircraft were gunning down civilians on the street.

And here we’ll get into one of the US’s biggest betrayals in the region. Western troops were still next door in Kuwait; Iraqi Kurds and Shi’a asked them for arms to protect themselves from being gunned down by Saddam’s military aircraft, but they were rejected because the West feared an Iranian-style revolution in Iraq—similar to the way they fear a Sunni-Islamist takeover of Syria. This betrayal by George Bush—it wasn’t until 2011 that the US ambassador to Iraq apologized for this.

Asking for protection flies over the head of many Westerners, because they don’t see human beings when they look at Iraq or Syria or Kurdistan, they just see geopolitical games. That the same civilians who have suffered from Western imperialism might still ask the West for help in the face of genocide is something they can’t comprehend.

I forget who it was, but an Iraqi Shi’a leader said, If you had supported us in 1991, that would have been a lot better than what you did in 2003, because in 1991 the uprising was led by the people. So this betrayal stayed in the minds of a lot of Iraqi Shi’a, and is the reason even people who celebrated Saddam’s fall didn’t trust the US. This was a huge betrayal. The death toll was somewhere between 20,000 and over 150,000, all within the span of a month. Even the Syrian counter-revolution took a long time to reach this sort of death toll.

A lot of commentators ask, Why would Iraqis and Kurds have trusted the US in the first place? I even saw this question asked in October when Turkish-backed forces were attacking Kurds in Syria. There’s an arrogance that underlines this question; it assumes that people in the region don’t know the US can be two-faced. I’m reminded of the list you put together of Syrian responses to Max Blumenthal’s articles slandering the Syria Campaign: one of them says, Yes, Max, the campaign is calling for a no-fly-zone, and that’s because a no-fly-zone is what Syrians have been begging for day and night.

This reaction asking for protection flies over the head of many Westerners, because they don’t see human beings when they look at Iraq or Syria or Kurdistan or wherever, they just see geopolitical games. So the fact that the same civilians who have suffered from Western imperialism might still ask the West for help in the face of genocide is something they can’t really comprehend—or don’t want to comprehend, because they’ve never been in a situation as tough as that.

This was a monumental event in the history of Iraq and Kurdistan. One grave uncovered after the invasion had as many as ten thousand Shi’a victims, in a single grave—so you can imagine the scale of this. These facts are really important to consider if someone wants to know the reasoning behind a lot of the sectarian conflicts that broke out after the fall of Saddam; it wasn’t likeSaddam fell and everyone just started going crazy. It had a lot to do with grievances from the past.

I think Iraq 1991 is a better comparison to Syria 2011 than Iraq 2003 is. Iraq 2003 was an invasion. It was regime change led by foreign forces. Ordinary Kurds and Iraqi Shi’a still celebrated the fall of Saddam, because why wouldn’t they? But Syria 2011 was a popular uprising. This is why the comparisons to Iraq 2003 don’t work at all. It was an invasion led by foreign forces. I always say to people: if you get hit with this argument—What about Iraq 2003?—ask the people saying this if they are aware of Iraq 1991, because they would know the price of not supporting popular revolutions when they do happen.

A lot of the tactics that Saddam used to crush the 1991 uprising are very similar to the ones that the Assad regime would use. Saddam loyalists would very openly shout anti-Shi’a slogans. They targeted Shi’a cities. It was very deliberate. We see the same thing with Assad regime soldiers and their anti-Sunni slogans and the targeting of holy sites. It’s very similar. Just flip the pages of the book back to Saddam and you’ll predict everything that’s happening in Syria now.

And Syria is headed towards a post-1991 Iraq type situation. A popular uprising was crushed by a dictator because the rebels were outgunned, and the country will stay broken and sanctioned and there is really no positive outcome. People say, Just let the Assad regime take over. Well, Saddam did take over the rest of the Shi’a majority south, and it didn’t end well for anybody. This comparison doesn’t work in any way, but it’s really hard to explain this if someone doesn’t even know the basics of Iraqi history—which is the case for a lot of people whose knowledge of Iraq starts in 2003 and who think that nothing happened before or after.

EA: I can sense the frustration in your voice. It’s something I understand fairly well—I’m not Syrian myself, I’m Lebanese, and I would never claim to know what Syrians are going through. But it’s something I became intimately aware of through personal connections and through my work.

During the fall of Aleppo and right after, in 2016, I remember the memorials and the stories that were coming out from Bosnia, from Sarajevo, of people saying, We know what it feels like to be abandoned. That made sense to me. But somehow I hadn’t thought of looking to the east of Ghouta, not even all that far away compared to Sarajevo. You write that many Iraqi Kurds, especially those from Halabja, were reliving their traumas when they heard of the Assad regime’s chemical massacre in Ghouta in 2013. One person that you quote in the piece even says, This is Halabja all over again.

You already spoke about this, but can you speak a bit more about what reliving trauma can look like? This is obviously very difficult. In terms of the emotional side of things—to move away from this obsession with geopolitics, as though we’re all just pawns in some big empires’ games—how was the chemical massacre in 2013 perceived by survivors of the earlier massacre in Halabja and the genocide?

SA: A lot of people don’t understand what the big deal is about chemical weapons, or how particularly horrifying the effects are that they have on a civilian population. Kurds have been hostile to the Iraqi state, to some degree or another, pretty much since its inception—but whatever small chance there was at reconciling Kurdish self-determination within Iraq essentially died at Halabja. The level of distrust and trauma that results from this kind of attack is one-of-a-kind. I don’t think any of the Syrian victims of chemical attacks are ever going to see the Assad regime or the idea of Syria the same way.

Chemical attacks have a psychological effect to a much greater extent than most other weapons, even though all weapons kill and injure, and ideally we don’t want any weapons being used against civilians. This is why the chemical attacks in Syria reawakened so many nightmares for Iraqi Kurds. You never really get those images, or that experience, or those stories out of your head.

We always get the question, Why would Assad use chemical weapons when he’s winning? I really wanted to address this in the piece, so I mentioned the example of a Free Syrian Army brigade which had been fighting the regime for years and never really gave up, but the moment he switched to chemical weapons is when they called it quits. That should give an answer to people who constantly ask why he would use them when he’s “winning.” A totalitarian regime has a very different definition of winning than most governments do. When you say to survivors, Why would a regime use this when they’re winning? it’s sort of a joke question. Like, I don’t think you understand why these weapons are used in the first place! It’s not just to regain territory—there’s a very deliberate message that these kinds of weapons send.

A lot of Kurds have correctly pointed out that if the world had taken a moral stance on Halabja, it would have been a lot less easy for the Assad regime to get away with chemical attacks in Syria. People have only heard about one or two of the chemical weapons attacks in Syria—there have been over three hundred. This is not something that just happened once a year; this is happening dozens of times each year.

I also want to stress that the normalization of chemical weapons hasn’t been limited to Syria. A lot of people don’t know this, which is really unfortunate, but in 2016 the regime in Sudan under Bashir used chemical weapons on civilians in Darfur. This got almost no media attention. So when chemical attacks are ignored in one place it just makes the entire world more dangerous in the long run. We’ve been hearing a lot of Syrian activists say this: What’s happening in Syria is not going to stay in Syria. There have already been many examples of this; this is just another one. We don’t want to normalize chemical weapons.

In terms of the trauma, it’s really incomparable. Another example I can give: when the attacks first happened in Syria, and Iranian soldiers (who as we know are backing the Assad regime in Syria) heard about this—there are articles and interviews—a lot of them immediately reconsidered their support for the regime. And these are people who up until that point had been killing Syrian civilians. So you can imagine the level of the psychological effects that it has; it makes even the people who are carrying out the genocide reconsider.

It’s really hard to explain, but with these tangible examples we can see that it’s not just like using any other weapon.

EA: The whole Why would he use this if he’s already “winning?” thing—it reminded me of Razan Zeitouneh, who you quoted in your article. Razan, for those who don’t know, is a very well-known and beloved Syrian activist, and a lawyer who co-founded the Violations Documentation Center—and was based in eastern Ghouta when the 2013 massacre happened. She was interviewed by Democracy Now! at the time, and that interview is scarred in my mind. I remember it so clearly even though I only watched it once—I couldn’t handle watching it again.

She was talking obviously under duress. Her English is pretty good, but not fluent; there’s an accent there—and she’s obviously talking on the phone under very difficult conditions, to put it mildly. And on the other line was Cockburn, an American journalist—or he used to be a journalist, I don’t know what he is now—downplaying what she was saying, using a variation of that argument. Why would he do it? Assad knows that if he uses chemical weapons the Obama administration will punish him, because that’s what Obama said he’ll do.

And yet, lo and behold, Razan was obviously right. She unfortunately paid a very difficult price for being so principled, just a few months later, when she was kidnapped most likely by Jaysh al-Islam, the rebel group that was dominating eastern Ghouta politically and militarily. We haven’t heard from her since. It’s been almost six and a half years now.

And that’s it—that was the end of it. Cockburn continued to write stuff after that, Razan was kidnapped, Democracy Now! continued. I don’t want to focus on Democracy Now!, there’s nothing personal, there is much worse out there than what they did. At least they spoke to Razan. Other people on the so-called left didn’t even bother to do that.

There’s really nothing surprising about what’s happening in Syria—very sad to say. I always recommend reading up on the Saddam regime to get an idea of the level of brutality that such a regime is willing to use.

But this leads me quite well, unfortunately, to the next question. It’s become very common for us to associate the Assad regime with a slogan that is repeated by his supporters, one that I’ve heard with my own ears from Hezbollah supporters in Lebanon. It’s usually associated with regime militias and soldiers—usually Iranians and Syrians, sometimes Iraqis. Assad or we burn the country. We’ve seen it written on walls outside of besieged areas.

This slogan has an equivalent. You talk about the Saddam regime; his cousin gained the name “Chemical Ali.” You write that he razed an estimated two thousand villages to the ground, and in one audio tape, he said, “I will kill them all with chemical weapons. Who will protest? The international community? Fuck the international community and those who pay attention to it. I will not just attack them with chemicals on one day. Instead I will continue for fifteen days.”

You can’t read this and still think we’re dealing with a situation where this is “rational,” as if these people are sitting around a desk and saying, This is enough, we shouldn’t do more than this, because we might have consequences, as if it’s all some kind of genius calculation, one of those board games like Risk or whatever. When people say Assad or we burn the country, it’s meant literally. It’s not a metaphor for anything. It literally means Either I stay in power or we burn the country. He even used the term “useful Syria” for the parts of Syria under his control—so some parts of Syria, the poorer parts, the parts not between Aleppo and Damascus, some in the north, some in the south, are simply not as important to him. He has said so himself.

Another relative of Saddam, general Mahir Abd al-Rashid, who I think is the father-in-law of his son—again we’re seeing the same Ba’athist logic of having families run everything—said, “If you gave me a pesticide to throw at these swarms of insects to make them breathe and become exterminated, I would use it.” This dehumanizing language—cockroaches, insects. It’s become such a common pattern. It’s such a part of the playbook of how a dictatorial regime is going to act that it baffles me to this day that we don’t see the writing on the wall as soon as this kind of language is used. In the case of Assad, we were already hearing this kind of language by mid-2011.

I was wondering if you could speak more broadly about how your own experience informed your reading of, or your reactions to, what’s been happening in Syria since 2011. Maybe you could also talk about the context of the recent uprisings in Iraq if you feel comfortable. But I would be interested in hearing what you have to say about your experience of Syria since 2011.

SA: I’ll first address the rhetoric around chemical attacks, and then I’ll get more into the Syrian uprisings. To understand this rhetoric that compares the population being genocided to pests or insects, we should really look at the roots of chemical warfare in the modern era. Sarin gas in particular was invented by a scientist in Nazi Germany. He was originally tasked with creating a pesticide for agriculture so that Germany could rely on domestic products instead of imports from elsewhere. So sarin started out as a project to get rid of pests.

You can guess where this is going. When you consider the rhetoric of tyrants who have used sarin or other chemical weapons—Hitler, for example, used Zyklon B. That’s another type of chemical agent—a blood agent, not a nerve agent like sarin. But he used these agents on Jewish civilians in gas chambers, and some could kill up to ten thousand people at once—which really shows the genocidal intention you would need to use such a thing. There are a lot of theories out there as to why Hitler never used them on enemy soldiers and only used them on innocent Jewish men, women, and children.

Conventional weapons send this message: We can kill you wherever we want. But chemical weapons send a slightly different message: We can kill you however we want. This goes back to the genocidal intent. We not only control whether you live or die, but how you live or die. It’s a step worse, if that’s even possible. This is why one chemical weapons attack can change the course of a war or an uprising, in a matter of moments—solely because of the psychological trauma inflicted.

This sort of exterminatory language that we see with Assad regime officials, just like Saddam before them—it’s very logical, given their views of “useful Syria.” When you say, Only certain parts of this country are useful, you’re saying the rest of it is populated by things we can get rid of. That is the implication of it. And they’re very honest about it, too, so I never understand why there is so much confusion about what is motivating the regime. They very clearly tell you. Not just Assad himself, but the shabiha too. All of his supporters are very clear about it too.

It was Martin Luther King, Jr. who said genocide is the logical conclusion of racism. When you say only certain parts of my country are useful, it’s not a big step from there to gassing people with sarin. It’s just a progression. Even before Anfal, Saddam’s crimes included rounding up and executing five to eight thousand young Kurdish men on the spot. So it’s not surprising that something like Halabja would happen. What was surprising is that people actually saw it on their TV screens.

Fortunately, back then there wasn’t a disinformation campaign like Syrians have to deal with. Even I am shocked that any post about chemical attacks—even ones that don’t mention the perpetrator at all, just extending sympathy to the victims—gets swarmed by denialists. I don’t know how Syrians deal with it. It’s important for us to keep combating this propaganda.

I’ve mentioned the Saddam regime’s targeting of young Kurdish men. In Syria, the targeting of predominantly young Sunni Arab men is very clear, in terms of who is being killed, tortured, and detained—anybody can look at the statistics. It’s very disproportionate. And it’s not just in Syria. Going back to the concept of gendercide, which targets not only a certain population but particularly the young men in that population: Israel uses this sort of rhetoric against Palestinians. Turkey uses it against Kurds. And even now Europe uses it against refugees, by saying it’s okay to shoot migrants if they’re not women and children—as if young men aren’t deserving of human rights.

This goes back to the idea that what happens in Syria doesn’t stay in Syria. The dehumanizing, fascist logic that we see has already gone way beyond the borders of Syria.

But another thing I wanted to talk about with regard to the uprisings is the nature of the Ba’athist regimes. By June 2011, the tally of casualties from all the countries that experienced the Arab Spring was very high. In Tunisia it was hundreds. In Syria the number exceeded one thousand. In Libya it was much higher. We hear people say, Bahrain had a revolution, why didn’t it end up like Syria too? but you have to consider the different natures of the regimes. Yes, there are a lot of regimes that are authoritarian, but there are different extents. In terms of the rate of repression, the Assad regime in Syria is really only comparable to Gaddafi in Libya and Saddam in Iraq. There aren’t really that many other regimes in the region that have this kind of burn the country logic.

A lot of leftists in the West find it hard to believe that dictators in the Global South can be as murderous as Hitler or Stalin. I think the reason is because they think people from the East have no agency, have no capacity to commit great evil or do great good. By their logic, only people in the West have the brains and agency to shift the course of history, to start revolutions or end them. Whereas the revolution in Syria in 2011 is similar to revolutions that have been happening all over the Global South. The heart of it is people realizing: We are just as deserving of freedom and democracy as anybody else. These regimes talk big, but their guns aren’t aimed at Western imperialism or Israel, their guns are aimed at us.

I saw an interview with Nisreen Elsaim, who is from Sudan, and she was talking about when Sudanese protesters targeted a gas station, and a lot of people thought they were just rioting, causing chaos. But she explained that it was a symbolic protest against the regime. Sudan is a naturally rich country, and the regime had been stealing the people’s money. Outsiders don’t know all this context and nuance. I didn’t know this until I heard a person from Sudan speak about it.

With regard to the Syrian uprising, if you don’t listen to people from the region—you mentioned that people only know a little bit about the beginning of it but don’t care to learn more. That’s detrimental, because they don’t just stop at, Okay, we don’t know anything about Syria. It goes a step further: It was a CIA-backed coup! If people would accept not knowing much about this place and were willing to learn, I think we’d be in a much better place now. Unfortunately that didn’t happen, so here we are fighting chemical weapons denialism, which is probably the worst place we could be.

The idea that so-called “Western” standards of human rights are exclusive to the West is really a racist idea, and unfortunately it’s shared by both the left and the right—and I wish it was just them, but also dictators around the Global South weaponize this belief. I remember an Indian politician saying that Western standards of human rights don’t apply to India. You can image how a person who says something like this will treat his own people. As you mentioned, when Assad supporters say Assad or we burn the country, they really mean it. It’s not a metaphor.

Flip the page back to the Saddam regime, because that’s where we see how a Ba’athist government actually operates. What does it do in the face of an uprising? It’s all already happened; the context is a little bit different, but it’s all very clear, so there’s really nothing surprising about what’s happening in Syria—very sad to say. I always recommend reading up on the Saddam regime to get an idea of the level of brutality that such a regime is willing to use.

EA: There’s that oft-used quote from [Maya Angelou], When someone shows you who they are, believe them.

You’ve been very generous with your time. If you had a note you wanted to end on, just go for it.

SA: Yeah, my note would be for people to prioritize the voices of survivors when considering policy responses to any horrific event—it’s very important to listen to the people who are actually experiencing it, because otherwise you fall into the trap of geopolitical chess, which is just dehumanizing and downright racist. So don’t do that!

EA: I think that’s a very good note to end on. Thanks so much.

SA: Thanks for having me.

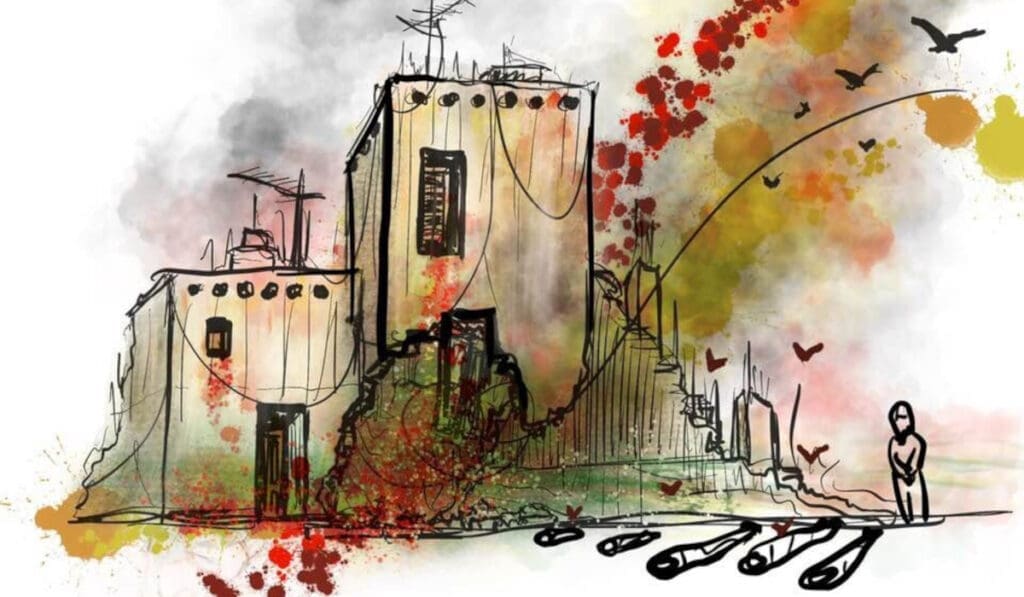

Featured image: “When Words Fail,” painting by Mohamad Hafez. Source: Mangal Media