Transcribed from episode 110 (6 February 2025) of the BULAQ | بولاقpodcast from Arab Lit Quarterly and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole conversation:

One of the things that really hurts about Syria, on top of everything, is also the narrative obfuscation that has happened. The narrative was abused, really. That’s a huge reason Syria was allowed to fester the way it did for over a decade; I don’t think we want to see the same thing happen now, moving forward.

Ursula Lindsey: Welcome to episode 110, and to a new season, of the BULAQ podcast. I’m Ursula Lindsey in Amman, Jordan; I’m joined by my friend and co-host Marcia Lynx Qualey in Rabat, Morocco.

Our guest today is journalist and writer Alia Malek, who is talking to us from New York but is actually just back from Damascus, and who we are so excited to have on to talk about Syria, what’s happened there, writing from there—we can’t think of a better place to start this new season than by talking about Syria, where the fall of dictator Bashar al-Assad in December [2024] has brought about such unexpected and long-hoped-for change.

Welcome very much, Alia, and thank you for making the time to talk to us today.

Alia Malek: My absolute pleasure. Thank you for having me, and thank you for all the work you do to bring poets and fiction writers to English-speaking audiences. It’s really important—more than ever.

Marcia Lynx Qualey: Thank you.

For those of you who don’t know her, Alia Malek is a journalist and former civil rights lawyer; she’s the author of A Country Called Amreeka: US History Retold Through Arab-American Lives, and The Home That Was Our Country: A Memoir of Syria. Born in Baltimore to Syrian immigrant parents, she began her career as a civil rights lawyer, then, in April 2011, she moved to Damascus and wrote anonymously for several outlets from inside Syria as it began to disintegrate.

This reporting from Syria earned her the Marie Colvin Award; she returned to the US in May 2013, where she is currently the director of international reporting at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

Most recently, she also edited an issue of McSweeney’s magazine dedicated to Syrian literature, titled “Aftershocks,” which by extraordinary coincidence was released in December 2024, just as Bashar al-Assad fled Syria and Syrian prisons opened their doors. The collection contains work by sixteen Syrian authors who write from diasporic and refugee experiences as well as from inside Syria—some of whom I understand you met with recently when you were just in the country.

Could you tell us about when you headed out to Syria, your experiences there, talking with the writers there, and what you witnessed?

AM: Prior to the fall of the regime, I was in contact for example with Rawaa [Sonbol], Somar [Shehadeh], and Fadwa [al-Abboud], who are the three writers who are inside Syria—along with many of the other writers. But it was a little bit surreal, because we had been trading WhatsApp messages in November: I was just checking in on them—letting them know that the book was coming out, making sure they would be getting their copies, little administrative things—and hearing how down they were, just in general, before the regime fell, and the sense of isolation that they were living in. And then a month later to be meeting with them openly in cafes in Syria, or even going on a hike with them, or attending literary events and civil society events that were happening all of a sudden after the fall of the regime—it was really surreal.

All of us had to keep looking at each other and being like, How did we all go from disembodied WhatsApp voices to flesh and blood? Syria right now is in a really incredible and interesting moment, and that was part of the specific interest (specific to us in “Aftershocks”) in this moment as well.

I flew in early January and just got back. There were other trips in motion, other things I had to do; I couldn’t leave right away. But I got to spend almost two weeks there, in Damascus and around Damascus, and then Aleppo and Idlib.

UL: I was going to ask about your impressions. I imagine this was—personally and professionally—such a momentous trip. Were there particular things that struck you or surprised you in this moment?

AM: Yeah. I’ve been processing this for weeks and days now. The initial twenty-four hours, it was almost hard to speak. I was in shock. As I try to deconstruct and think about it, it was an exile that has come to an end for me and for many other Syrians. That’s not a unique experience in the world, but it was a fourteen- (or in my case, since 2013, twelve-) year exile.

Everything was not particularly changed, even as it was completely changed. When I returned to Damascus, everything was still muscle memory. There were no landmarks that were gone inside Damascus; all the roads were the same; there were no particularly new buildings in the urban landscape. At the same time it makes you realize—I just kept thinking about wasted time.

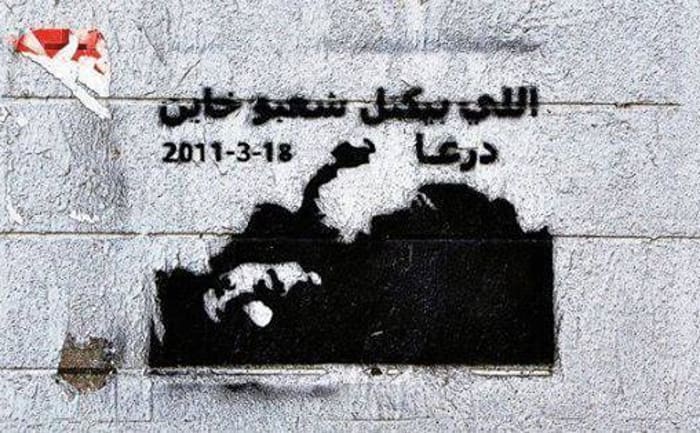

In 2011, it looked like there could be reforms, if not the fall of the regime—or an openness to a new Syrian future whether or not Bashar al-Assad and the regime were part of it. If you recall, the initial protests called for reforms, not for the fall of the regime. The spirit I moved to Damascus in, in 2011, and that a lot of Syrians greeted that moment with, is the same spirit that they’re greeting this moment with as well: this ability to be part of the future.

But because it was not that long ago, it somehow is just pointed out to you even more: Why did we have to go through these fourteen years of trauma, destruction, displacement, and disappearances? I talked about this with some people; somebody said, We’re much more ready now than we would have been then—we had to go through all that. But I don’t know. I guess that’s a silver lining. But a lot has happened, a lot has transpired that it feels like it didn’t have to.

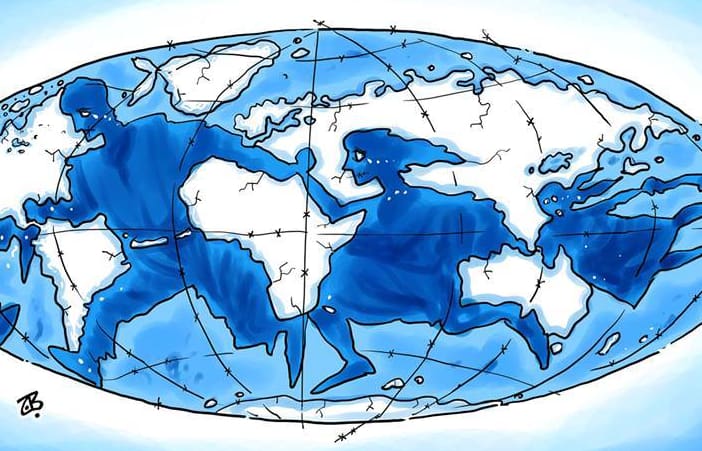

Because there was an inevitability to the idea that one day this regime would fall. Even as all indications—even as of November—were indicating we were full speed ahead on normalization with Assad, I do feel like there was a sense that this was completely against the will of the Syrian people. The will of the Syrian people had been expressed in 2011, and even more in the mass migrations. People spoke with their feet in a country where you can’t necessarily speak in other ways. People’s willingness to leave and cross borders was a way of speaking with their feet, and the will of the Syrian people has, for a while, been not to live under this regime.

That’s all I could keep thinking—because it was so familiar. The places were the same. It wasn’t dramatically transformed. That’s inside Damascus, of course. I went to places like Jobar and Ghouta that have been completely transformed and destroyed—which kept reminding me, again: What was all that for, to get to a place that was inevitable if you were to follow the will of the Syrian people? That’s where I kept getting stuck in a loop in my head.

But it was also incredible. Before the revolution, my experience of Syria—having been a human rights lawyer and then a journalist, I never worked there as a professional; those are hazardous-to-your-health occupations in Syria pre-2011, and after 2011 through these horrible years of darkness. So it was really after everybody was displaced that I began to meet many of the Syrians who I didn’t get a chance to know inside Syria. I knew some of them, but now I feel like I know all the Syrians. It was incredible—so many people came back so quickly, to grasp the moment. It was incredible to keep bumping into people I know from outside of Syria, all of a sudden to be inside Syria with them again. It gives you a great sense of optimism.

But also, the way that people were received by the very weary and wary people who have had to stay through all this time—the fault lines that divided Syrians before all of this were several and probably well-known, but now there’s a new one, that we’ll have to work very fast to stem becoming a scissure: between people who had to remain in regime-controlled areas versus those who were in non-regime-controlled areas versus those who were in complete diaspora. How each regards the other is a new thing that could potentially divide us.

I think people have seen that and understood that, and there needs to be a period of validating and recognizing all the different kinds of experiences of what it meant to be Syrian in the last fourteen years.

MLQ: You were born in Baltimore. What brought you to writing about Syria, to moving there in April 2011? What was your early relationship with Syria?

AM: For the first six years of my life, we were back-and-forth, and then in 1980—this is what the book is about: the house that was intended for my mother, in 1970 my grandmother (while my mother was still in college) rented it out for what she thought would be a year, to a man discharged from the military. This was the same year Hafez al-Assad comes to power, the same year my great-grandfather dies—all these multiple events happen, all right at the same time, which made it a good metaphor for the book: neither the tenant nor the president ever left.

So we didn’t have a house to come back to, and then in 1980 my grandmother—my family is from Hama; there was somebody murdered in our family, and there was a decision made not to come back. But my parents’ nostalgia, or also trauma—being displaced in the seventies and eighties is different; it’s not so easy to be connected to home—we were nursed on that, and being the firstborn I got it the worst.

I also had all these memories. There’s another symbol at the heart of the book in terms of what happened to my grandmother, also in 1980. For me, my memories of Syria, my memories as a child, were completely intertwined with her. I don’t want to give it away, but something happens to her that becomes a great metaphor for what happens to Syria. So I feel like I was always chasing Syria, or Syria was chasing me, for most of my life.

I did work in the Middle East, and I wrote about the peoples of the Middle East, and then in 2011 when it seemed like something could happen that would change the frozen nature of Syria for me, I wanted to be there for it. That’s what I mean; in 2011, I was like, I don’t know what I’ll do, but I’ll be there to be part of whatever the country needs in that moment (and that’s also how I’m thinking now).

That book was maybe my entire life in the making; now I had the skills, after becoming a journalist and a writer, to try to approach it. I guess in some ways it’s a diasporic cliché, but I hope I didn’t approach it in a cliché manner; I tried to approach it as a journalist, with the skepticism and rigor that journalists supposedly have. It’s not the only thing I write about or the only thing I work on, but I do feel—especially as I’ve gotten older—that it’s a story I have particular access to, and I don’t have to play catch-up.

I watch a lot of journalists playing catch-up. It’s hilarious—I teach journalism, and all my students are like, Oh, we follow so closely what’s happening in the Middle East and Syria, but then when you push them, they really know very little past the last few months’ news cycle. I don’t think knowledge that’s built about the place is served by that kind of limited interaction and engagement with the place.

MLQ: To clarify for people listening who want to read the book now, she’s referring to The Home That Was Our Country: A Memoir of Syria.

AM: Which ends in a very sad way, and now it needs a new epilogue.

UL: That could be nice to append.

And you’re absolutely right that it is unique to bring deep, long context to writing about these places, especially for a Western audience. And writing about the diasporic experience or about exile—I wouldn’t say it’s a cliché; I would say it’s part of Arabic literature for a reason, because it’s been so much a part of the modern experience in the region. It’s almost a literary genre, with eminent proponents.

There’s a reason for that, and I was going to ask you, as you reconnected and traveled back to Syria, if there were any particular books or writers that were important to you or that you would recommend to people who want to learn more about Syria or Syrian literature and get past the headlines, and start to be introduced to the broader writing.

We often get the question of where to start, and I’m always looking for good recommendations.

AM: Well, obviously “Aftershocks.”

But I’m super fond of Khaled Khalifa. It’s devastating that he didn’t live to see this moment. A lot of people have been thinking about that, too. My father died in 2019, at it was constantly his dream to go back. Syria was already pretty bad by the time he died, and he had given up on his dream to be buried back in Syria. He was sick for a few years, so he had the luxury of being able to plan his death. I wrote an essay about this for the New York Times a few years ago.

I’m not alone in this. I, like others, went from a place of I guess it’s good that so-and-so didn’t live to see how bad it continued to get—even though Syria was already an abyss: the normalization of Assad, the idea that all this was for nothing, was the final knife in every Syrians’ hearts or backs—and then we shifted to I can’t believe they weren’t alive to see this moment, to be here for this moment.

Khaled is somebody a lot of people think about in that way. I guess that’s where I would start, if I were to tell somebody coming newly to Syrian writers.

UL: His work fortunately has been translated into English quite extensively.

But also, all the writers in this collection are living Syrian writers; it’s a collection of so many important writers—

AM: And unknowns as well.

MLQ: Certainly unknown in English. Jan Dost will have his first novel out in English translation in 2025; Mustafa Taj Aldeen Almosa also will have his first collection out from University of Texas Press in 2025.

Syrian literature was lesser translated—though remaining a vibrant space both in the diaspora and among Syrians in Syria—but it was lesser translated than Egyptian literature for example.

AM: Is that true? You would know better than me. But yeah, I don’t know why that is.

MLQ: It’s translation pathways. A lot of translators went and studied Arabic in Cairo, but didn’t necessarily engage or weren’t in Syria as much. Translation is also a lot about connections. But now, the more Syrian literature that comes on the landscape, of course the more people get interested.

AM: That was the whole goal—when Dave Eggers and I started talking about this a few years ago, he gave me carte blanche. There are Syrian writers who have been translated quite a bit; there are Syrian-American writers out there—and I made a pretty fast decision not to do that, that what I wanted was audiences who rarely get to read Syrian writers in English translation to get an introduction.

Of course you guys at Arab Lit Quarterly have done so much of that amazing work; McSweeney’s is a different audience. This is an audience that is coming for literature; it doesn’t matter where it’s coming from.

I think this cost them a lot of money! I kept bringing them stuff and I was like, Well, it’s going to have to be translated! And McSweeney’s did a lot of the translation. There are some things where I talked to translators, and Marcia helped connect me to the right people who were already working on something, so I could see it in English. But then we went after a lot of people who submitted in Arabic, and McSweeney’s covered the cost of translating it—and it was sixteen writers! We have to shout them out, because these are usually much smaller collections. But Dave was all-in on it.

And we had no idea when we started working on this that it would coincide—the book came out four days after the fall of the regime. We went from Are we going to get this book any attention? to all of a sudden—I’m calling it a book; for people who don’t know McSweeney’s, it is a literary magazine but it’s quite thick. They look like books much more than magazines.

And it’s not perfect; we had time limitations, it was hard getting people. People I solicited couldn’t get something in. I would have liked—I think we have six women and ten men; in a perfect world it would have been a better mix. But we have people from all sects, from all ethnicities. I tried to approximate as much as possible, to capture the diversity that makes Syria.

What do you guys think? I don’t work in literature. I was also really hesitant to do it. I told Dave I come from the world of nonfiction. I kept trying to back out of it, or say that I wasn’t the right person to do it. I don’t know—how are the people in this world receiving it? This is your world.

MLQ: I think you were the right person to do it. You did bring together so many of the most vibrant and extraordinary Syrian writers working today, and also in a variety of genres. I love that it’s not just fiction but also playtexts.

AM: The only thing I was sure I didn’t want was poetry; sorry, poets. I just wasn’t in that headspace—I love poetry; I consume a lot of poetry, and had you asked me about poets, I could probably tell you more about Syrian poets than fiction writers. But I think there’s something about fiction (and I put plays in that world) that allows for the creation of a little bit more—you can spend more time in that world.

And poetry can be a world—I’m going to get a lot of hate mail now. But I just had a strong bias that that’s what I wanted readers to be exposed to.

MLQ: As the editor of the anthology, you have to make some decisions; you decided you wanted living writers as well.

AM: Yes, and who had written in the last ten years. Only one or two people—three, maybe—wrote something new specifically for this issue. I didn’t want to shut down the opportunity. Also, it’s not like there is massive amounts of money in this, what’s paid to the writers. I really wanted them more to get translated, and I came up with a theme that I thought provided for a lot of—it was open enough that people could find something that would speak to the theme without having to write new.

MLQ: Right. And the theme is aftershocks: anything coming after a seismic event. So, letting people determine what a “seismic event” is, broadly.

AM: Yeah. I was also in that headspace; when I came up with the theme, I think I had just come back from reporting in Turkey after the earthquake. And it’s not that I was thinking about the earthquake as much as how from crisis to crisis to crisis, there were so many seismic events in Syrians’ lives. It was really more about “after the shock” as opposed to an earthquake aftershock.

I was struck by one of the things Syrians said—which is in the introduction: so many people said to me, Oh, the only thing we haven’t seen are dinosaurs and volcanoes! It’s funny and dark and bitter. So yeah, I thought that would cover a lot of territory.

And somebody said—Mohammad al-Attar was like, It’s too bad we weren’t writing for after this moment! Which is true, but there’s nothing that says this is a one-time thing. I would think there should be anthologies all the time. And I’m happy to report that one of the short stories in this collection will be in the new—John Freeman and Rabih Alameddine are editing an anthology of international short stories, and something is coming out of “Aftershocks” into it. And not from one of the more known writers, internationally, so I’m really happy about that.

UL: One of the things that this anthology captures, like you say, is the prevalence of the funny, dark, surreal aspect to contemporary Syrian literature, that there’s this line that so many of the pieces walk.

AM: Yes, it’s by necessity. By the inability to speak freely.

UL: But the dark humor that comes through in so many pieces—is that by necessity, or is it a way of coping?

AM: The dark humor specifically? It’s a way to comment on the absurdity. We were, have been, and are living in absurd times, absolutely absurd times—and it’s only getting more absurd. I think it’s a way to greet the absurd, to engage with the absurd. Sometimes more than a polemic, it’s better at holding up a mirror to the absurdity of our times.

UL: Perhaps this would be a good spot, Marcia, for you to read an excerpt from one of the stories that struck us all.

MLQ: It’s hard to choose. There are many great contributions in here, but we settled on one that we would like to share a bit of—also because it comes in sections, so we can read one section of it.

This is from “Diary of a Cemetery” by Fadi Azzam, which was translated by Ghada Alatrash. This occurs in the Cemetery of the Martyrs, and it showcases this line between darkness and humor that comes in a lot of Fadi’s writing as well. It’s after our narrator’s skeleton is sold off to the College of Medicine, and because he’s missing an arm, a woman’s arm is attached in place of his missing one. After this he begins to chatter uncontrollably, panicking the anatomy lab—and this leads to the next section, “A Special Celebration.”

By way of atonement and reparation, a new spacious grave was created for me. Above the grave was a large and hideous monument in the shape of a helmet, with the inscription “Here lies an unknown soldier who has sacrificed everything for the sake of the homeland.” Heaps of fresh wreaths were piled on top of the grave before the crowd departed solemnly.

After the celebrations ended, I felt a sense of pride and slept soundly for the rest of the night. In the morning I was awakened by the sound of a herd of goats nibbling at the wreaths of my shrine. I was grateful for the goats, for when flowers and garlands become moldy, they are known to cause us unpleasant allergies.

My colleagues were eager to visit and welcome me back. But they were filled with envy, not because of the wondrous journey I’d taken, but because of my new arm. They raced to congratulate me and shake my female hand. To be honest, I did not like what was happening. The fact of the matter is that corpses also have their boundaries!

I never expected a visit from the Wiseman of the Chinaberry Tree. He was a highly respected martyr, and it has been said that he was the first to reside here in the cemetery. His grave was spacious, and located under the giant chinaberry tree at the top of the hill. He seldom left his place.

We talked for a short while. He asked me about the living and their world and how things were. I recounted everything I saw. He was especially curious to hear about how the city was boiling with fear and anger, and of the latest talks about the protests that were taking place in neighboring countries, and beginning to reach our borders. I told him that I noted many soldiers in the streets, as if a new war was about to break out. He then asked me about my arm, and I explained what happened. Before he left, he extended his left hand to shake mine. I didn’t want to turn him down, as it was obvious that he, too, wished to touch it. I raised my new hand carefully to rest it in his old palm, allowing for the thunderous heat to flow into his body. At its touch, life seemed to return to him and he no longer looked exhausted and weary. But as he began to squeeze it, I felt annoyed and afraid, and I pulled it out of his hand with difficulty. Apologetically, he muttered, “I am not sure what has come over me!”

And this ends: “Note from the investigator” (who is annotating this diary): “It should be noted that these events took place at the beginning of 2011.”

So it’s also a sideways glance at what’s happening in the country, through these skellies.

UL: That story is wonderful, and it had that quality which I always love: I was completely surprised at moments in it. The complete freshness of a turn, like this twist with the arm that is added to his body, that turns out to be a female arm, and that exerts this fascination on all of them.

The sadness of the story, though! I’m trying to put this into words. It’s funny, but the sadness comes somewhere from this ineffable feeling you get that—how to put it—that the bodies in this graveyard are somehow safer or more at peace than the living people. You get this feeling that being alive—there’s something so unhappy and dangerous and tense, that they’re almost safe, the little skeletons huddling in the graveyard. That’s the feeling I got from that story.

AM: Maybe in that story. But in some of the other stories, the dead do not rest either. I don’t even know if in Fadi’s story I would say—it depends how you define “safe.” But I found that even in death there was no rest. That’s how I read that.

MLQ: That’s true, he was bartered away in order to get their petition—how did he end up in the College of Medicine? His bones had to be bartered away. It’s interesting because it’s also a parallel space; there’s different things happening among the dead than among the living, and there’s an overlap—and in that space where they rub up against each other, so many interesting things happen.

UL: It’s not a super original observation about contemporary literature, or Syrian literature in particular, but I was also struck at how many of the stories had a very non-linear, fragmented—to the point where sometimes it was not easy to follow the plot or the narration, and you just had to leap with your imagination, forwards through these images and these scenes that come at you quite like dream or nightmare fragments. They have a logic of their own, but it’s not often a traditional narrative logic. There’s a considerable number of the stories that have that formal element, to some degree.

AM: That’s true. I think that’s because a lot of people are processing what’s going on through writing, and it’s hard—I say in my nonfiction book, I have a sentence somewhere: “A story about yesterday usually begins a hundred years ago.” In many ways that’s the one thing that’s true to the experience, the disjointedness of it. Because time and space are disjointed for Syrians. Lives are interrupted and resumed in different places. As much as there is so much magical realism and a surrealism to the stories—that’s actually very literal to the experience, the disjointedness. I’m thinking on the spot as we speak through it.

One of the things I kept wondering about—one of the translators, Katharine Halls, happened to be in Syria at the same time, so we were all together at one point: me, Fadwa, Rawaa, and Katharine. And we were having a conversation about where Syrian fiction goes now, now that there aren’t these restrictions on speech. It’s going to be very curious if there’s some kind of turning point in how Syrians talk about life going forward.

What will change? I think the selection of style in many ways was a function of restrictions and fear. Does that look different now in a post-Assad Syria? That should be somebody’s PhD dissertation.

MLQ: You put me in touch with Rawaa as well, and she told me that in the past she used this elusive metaphorical language that she trusted to suggest more, and trusted a reader that would collude with her to pick up the hints and complete the stories. She was still figuring out—where does she go next? How does her language change? She said, I don’t know.

AM: I think she hasn’t been able to write since. She said something to me, and we had a conversation about that.

It’s really going to be fascinating. This is not something I will follow as a professional, but I will be curious to see what changes. That’s one of the reasons—when you said to me, Who are your favorite Syrian fiction writers, I like Khaled because, as a nonfiction person, I think you can be literal and it can still be surreal. But sometimes that magical realism that you find in Syrian fiction to me is—as Ursula was saying, it can make the experience a little bit harder as a reader. It’s why I was drifting much more to nonfiction, or the more literal novels.

I don’t mind it in my poetry—that’s one of the things I don’t mind in fragments.

UL: One of the writers I’ve been thinking about is Sa’dallah Wannous, who was one of the first Syrian writers/playwrights that I really got interested in and read and wrote about. There’s a very nice English collection of translations of his work that came out five or six years ago. And his daughter, Dima Wannous, is one of the contributors to your collection.

That’s writing that completely remains resonant in the current moment—his, and she wrote a very beautiful novel that Marcia and I both quite liked very much, called The Frightened Ones, which was about the Syria of Bashar al-Assad. But it’s not like that heritage has completely disappeared either; that will be part of the story going forward, it’s just that now there’s another story to tell as well—many, many more stories to tell, which is a great thing. Of course, all those previous stories, when they were told well, they will also continue to be part of the story.

It takes time for people to process these things, so we will see. Writing takes time; I’m not surprised that your friend is not currently writing, because it takes time to process a moment like this.

AM: Absolutely. People right after—on December 9, editors were asking me if I wanted to write an essay or an op-ed. I was like, Give me a second!

I always have a little self-loathing when I write an op-ed, because I find them—I’m much happier in a space of reporting. But I did end up doing one that just came out, because I did feel that there were things that needed—it was more about having an opportunity to speak back. One of the things that really hurts about Syria, on top of everything, is also the narrative obfuscation that has happened. The narrative was abused, really, so I finally relented and wrote this essay because I could see that that same narrative obfuscation was happening again. I really think that’s a huge reason Syria was allowed to fester the way it did for over a decade. I don’t think we want to see the same thing happen now, moving forward.

I’m still processing; I kept seeing people I hadn’t seen in a long time, and we would just sit there and kind of stare at each other. It’s a kind of hysteria. The way I put it in the essay—I think I said, For fifty-four years, the tab between the Syrian people and the regime was left open. On that tab are displacements, disappearances, and so on—and now all of a sudden, on December 8, that tab closed. There’s something about a deferment, when that tab is open and all of a sudden you have to cope with it; it was a moment in which tallying could happen. And that’s pretty decimating. It’s soul-crushing, and it’s overwhelming in its relief.

So I did feel like a lot of people—all of us—were suffering from, if not hysteria, just a whiplash. That’s why I was saying it was a catharsis and also an exorcism; it did feel like that. An exorcism is also brutal, even as it’s liberating.

MLQ: Can you talk a little bit more about that narrative obfuscation that you’re talking about, and the contours of it?

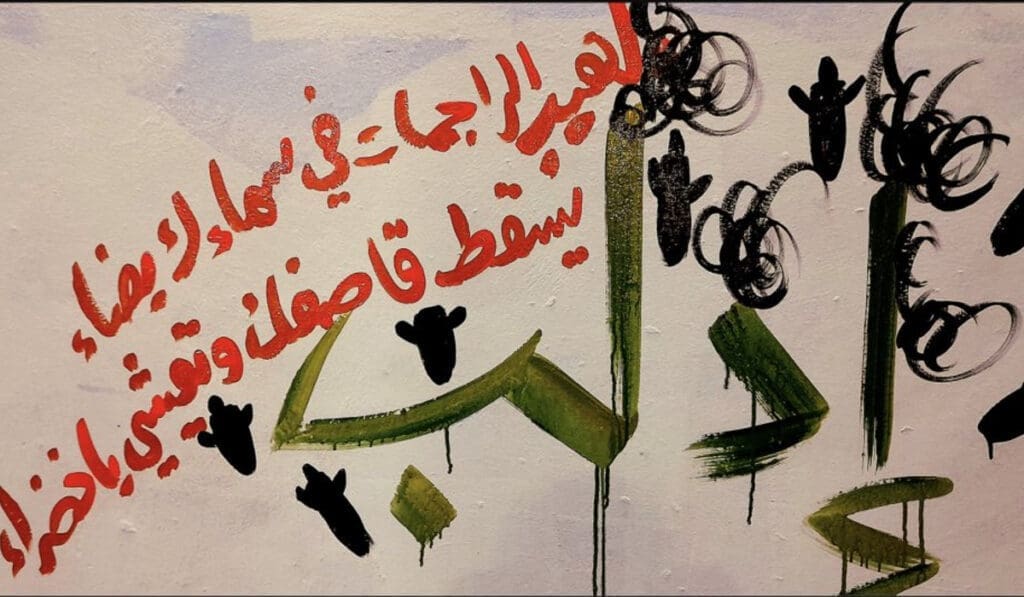

AM: Yes. Basically, the regime, in the first instance, in 2011, was the first to be like, No, this is not an uprising of normal people; this is foreign-funded extremists working on behalf of Israel and the United States and the Gulf to put through regime change! Assad is a secular leader! These people are trying to make it jihadist chaos like we saw happening in Iraq and other places!

And that just kept growing for years. It’s picked up on by an international roster of pundits and influencers and so-called “journalists” who just kept pushing the line that Syria and Iran and Hezbollah were an “Axis of Resistance” to Israeli domination, and it was Israel and the United States who were fabricating these reasons to cause “regime change.” And the reason it took such hold is because there’s some plausibility to that. The US did do terrible things in Iraq and destabilize it to create regime change with a false narrative.

The way disinformation works—this is something I do as a journalist—is if it complies with your world vision it’s easier for you to believe. And a lot of people’s world vision was that the only imperialistic actors in the region are the US and Israel and the Gulf—failing to see that Russia and Iran on the other side also have imperial designs on the region. So for a lot of these people, Assad was not shooting at innocent Syrians, but rather putting down these paid fighters.

This is what’s so painful. It totally wrote the Syrian people out of their own story. Syrians are only idiotic pawns or puppets, if anything—naive, but not really protagonists in their own story. And we were seeing it immediately when the regime fell and people were celebrating: these same people were just like, Oh, what are you celebrating? You’re about to become Libya! You just became an Israeli this or US that.

What is critical, and what I was arguing in this op-ed I keep referencing, was that you cannot write the Syrian people out of their story again. That was the reason so many people misread what was happening in Syria—and continue to! People tweet at me or send me shit that says, You are so stupid, this is just regime change, this is what the West wanted, they want Syrian resources! And there’s always truth to the malignancy of Israeli or US motives in the region, of course. But the Syrian people are also part of this story, and what they want. Of course they have agency!

I feel like we’re heading down that road again, where people are still failing to see, and also misread, why a lot of Syrians are willing to engage with the new government. That is what I kept hearing over and over, from civil society people of all sectors, from international Syrian civil society to the local to the ones who were working in Idlib and in “liberated areas” under HTS and the ones working in government/regime areas: nobody is naive as to who HTS were, or the new head of the caretaker government, Ahmed al-Sharaa (once al-Jolani).

Nobody is stupid. But they can get in on it and try to exercise some kind of agency over what happens next in the life of Syria. I think a lot of Syrians on the ground feel that there’s maybe six months to nine months to a year in which there is that opportunity, before these people stop listening. They didn’t plan to take over an entire country, so they’re open to listening to the expertise of other people—but at some point that window will close.

So this constant rhetoric that Syrians are just naive and they don’t know that it’s not that they’ve been liberated but that the regime has been forcibly changed—it’s just…Shut up! Have some decency! You were also wrong all these years! If anybody continues to tell me that Bashar al-Assad was resisting Israel by locking up Palestinians and Syrians and putting people in dungeons—they’re still maintaining that line! Zero decency.

Sorry, that was a diatribe. But it’s years of anger, and all Syrians feel that way. It’s not just me personally. And it’s frustrating, especially for those of us who think in terms of narrative.

UL: And also, on the part of people on a different side of the political spectrum, there is this incredibly condescending approach where the immediate concern is, Oh, extremists! or Instability! or Immigration! or something like that—or suddenly a concern with the rights of women and minorities. Like, now you’re concerned? The utter hypocrisy is like you say: it’s scandalous, in the utter disrespect for people who have been through everything.

AM: But they’ve made money off of it. They have huge social media followings. There are people who continue to discount anything Syrians say. I’ve had stuff sent to me like I’m not a “real” Syrian, like, Here’s what a real Syrian living somewhere here says: they’re slaughtering minorities in the street! Which is not true.

Sectarianism is not going to disappear, and it is reinforced by the fact that the regime had a sectarian face, for all its claims to secularism. There is a lot that needs to be done in Syria; to have to open up this front where you also have to respond to the narrative obfuscation—nobody needs that now. The country has been destroyed. People are hungry, people are poor, people who were comfortably middle class are not anymore. There’s no electricity. Do we really need to be talking about this and having to break down disinformation when we have real things that need to be taken care of?

I don’t know how we got here, but since we work in narratives—I feel bad because your listeners want to hear about something literary.

UL: But literature is produced in context. I would say actually, as much as one can, one should just ignore this noise and do things like instead read your beautiful collection of writing from Syria, from today, and then search out the other things that these writers are writing, and inform oneself as much as possible from real, honest, thoughtful places, and not just follow the news but be curious about everything, all the forms of writing and storytelling, because those are as revealing and as interesting as anything else.

Is there anything else you would like to highlight that you’re doing soon, or that’s forthcoming for you?

AM: I’m taking a moment to step back and see what role I can play, whether it’s supporting local journalists—I don’t know that I want to write, per se. I want to process, and listen to the needs, and see what role—having been in this game for a while, there’s more that I can do than merely chronicle as a journalist what’s happening. And obviously Syria is being swarmed with journalists now. It’s just the nature of the beast.

I wish I could tell you. I should be trying to plug something.

UL: You landed back forty-eight hours ago. You don’t need to have it all figured out!

AM: I do want to plug “Aftershocks.” I think it’s so good. Somar Shehadeh, who I got to meet, who came in from Lattakia to see me in Damascus, is on the Booker [International Prize for Arabic Fiction] longlist, as is Jan [Dost]. He’s also up for the Sheikh Zayed [Book Award]. It’s just such a great collection; I’d rather plug the collection than anything I’m about to do.

And who knows what I’m about to do! It’s an overwhelming moment, it’s a huge opportunity—as 2011 was. I would just tell people to listen to Syrians as much as possible, as opposed to people who would speak on their behalf.

UL: Those are words of wisdom with which to end perfectly.

MLQ: Thank you so much for joining us today, Alia.

AM: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for the work that you all do. I love Arab Lit Quarterly. Shout out to all the translators, because they are the ones who open doors to other worlds for people who don’t read in the native language.

UL: Thank you again for joining us. Goodbye to everyone who’s tuned in, hope you enjoyed this episode.