AntiNote: The following are two recent interviews with a fellow From The Periphery media collective member, Leila al-Shami, published in different leftwing anglophone outlets. We have lightly touched up some of the editing for clarity and accessibility, and packaged them together primarily for ease of sharing her vital message. We encourage readers to visit the originals linked below for additional context—the New Internationalist interview was paired with another speaker, for example—and to support both outlets who gave us their kind permission to reproduce their work.

Syria’s Political Future Post-Assad

Interview with Leila al-Shami

by Maxine Betteridge-Moes for The New Internationalist

11 February 2025 (original post)

It’s still unclear what different blocs and actors are going to be coming forward in the political process, but what we do have in Syria is thirteen years’ experience of revolutionary organizing, and this shouldn’t be overlooked.

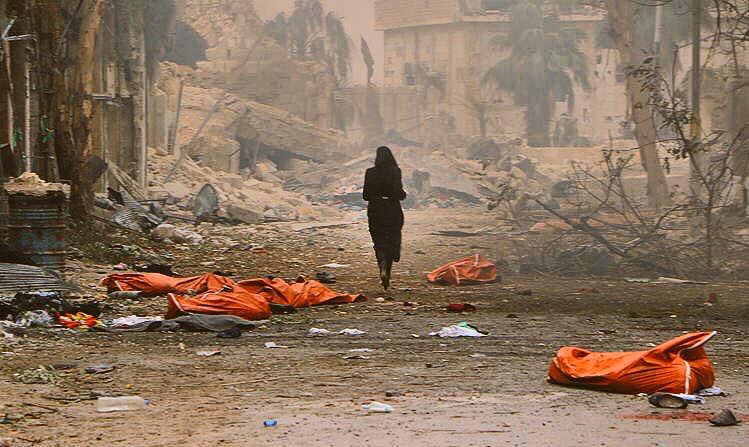

Maxine Betteridge-Moes: A flurry of media coverage in the days and weeks following Assad’s dramatic fall showed clips of desperate families searching for their loved ones at the notorious Sednaya prison, highways jammed for miles with cars returning to Damascus, and the tired but joyous faces of Syrians proudly waving their flag.

But the international implications of this historic moment will continue to unfold for months and years to come. Israel is moving quickly to expand its illegal occupation of the Golan Heights in southwestern Syria, pushing further and further into the territory with the help of US weaponry. Europe, meanwhile, is freezing asylum applications for Syrians, many of whom will return to their country amid mounting humanitarian challenges.

I spoke to a prominent voice on the Syrian left about what international solidarity with Syria should look like in the months and years ahead. Leila al-Shami has been involved in human rights and social justice struggles in Syria and across the Middle East for twenty-five years. She was politically active during the Damascus spring in 2000 but had to leave Syria for the UK because of her political activities. Up until the fall of Assad in December and the takeover of the country by HTS leader Ahmad al-Sharaa, she says it wasn’t safe for her to return.

Leila al-Shami: I’m Leila al-Shami; I’m the co-author of a book on Syria called Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War. And I’m also a co-founder of From the Periphery media collective.

MB: Since the fall of Assad, has there been an emergence of other political opposition and political organizing in Syria?

LS: On the political level, we need to understand that Syria has just come out of five decades of totalitarian dictatorship, where all political organizing was destroyed and repressed very violently by the regime. In addition to that, we’ve had a decade of incredibly brutal war, so we don’t have lots of established parties and different opposition parties. This really needs to be worked on now, of course; parties like the Muslim Brotherhood have been a key actor in Syria historically, and there are a lot of different forces, but it now takes time for those forces to start organizing themselves and putting forward a political program for the next phase.

I think it will be very interesting in the coming months, when we have this national dialogue conference which Ahmad al-Sharaa has promised, to see how inclusive and representative that is of the different factions and strands of Syria’s diverse political culture, and how those groups are going to organize going forward.

Even when we talk about Sunni Muslim politics and people who want a more Islamic framework, there’s a very big divide between the Muslim Brotherhood—who want a kind of moderate, modern, neoliberal version of Islam—and more hard-line Salafi groups, who might not be happy with some of the moderation that Ahmad al-Sharaa is talking about, or using that kind of discourse. So it’s still very unclear what are going to be the different blocs and actors coming forward in the political process, but what we do have in Syria is thirteen years experience of revolutionary organizing, and this shouldn’t be overlooked.

MB: What, if anything, remains of the country’s labor movement? And what role should people outside of Syria play in shaping the political process?

LS: Organized labor hasn’t been a big factor in Syria, because when the Assad regime came to power, it crushed any independent labor organization and trade unions, and instead built up parastatal organizations which were said to represent the interests of workers, but really just represented the interests of the Baathist regime.

The other thing, of course, is that leftist ideals have been very discredited in Syria because the regime presented itself as a “socialist,” and also because so many on the left [internationally] didn’t stand with revolutionary Syrians but instead supported the Assad regime. So there’s a lot of work to be done. Of course, there are many Syrian leftists, and they will be organizing now and meeting and discussing the next phase. But in the past period, people have been working on survival, nothing else.

It’s the responsibility of people on the outside to stand in solidarity with progressive and democratic forces that are working on the ground. The international community spectacularly failed Syrians over the past thirteen years. Now it’s really time to get it right. We ourselves have also learned the importance of making visible some of the forces on the ground which haven’t been as visible as the armed militias or the Islamists—the media likes to focus on those kind of aspects; it’s much less interested in civil organizing and democratic local councils, but those have always been the backbone of the revolutionary struggle.

Syrians also have a lot of work to do to ensure that those voices are reaching an international audience, so that people can give them proper, meaningful political and material solidarity and support.

MB: You’ve written that a secular society can best represent Syria’s diverse social fabric. What do you mean by this? Is it a view that’s widely shared among Syrians and in the diaspora?

LS: That’s my personal belief, not only for Syria, but for anywhere. But especially in Syria, where there is such a diverse mosaic of different religions and ethnic groups, in order to have stability and for everybody to feel included in the political process and included in the cultural, economic, and political life of their community, a secular society could best ensure that. Minority groups don’t want just to be paternalistically bestowed a few rights in a system that they don’t feel represents them.

There’s many people who believe in secularism. It’s a very diverse group of politics, whether that’s conservatives, liberals, leftists; there a lot of Sunni Muslims who are religious but believe in the separation of religion and state. The question is—given that these are such divided constituencies—whether they can come together to to put forward a secular agenda that will be able to include all their other demands, which could be quite differing.

These are all questions that need to be worked out. I’m much less concerned as to whether we have an Islamist government or a secular government, as I am concerned about whether this is an authoritarian government or a democratic government. This is the key dividing line that Syrians have been mobilizing around: to put an end to authoritarianism. What we should be pushing for is to ensure that there’s a democratic space, and once there is, that Syrians are able to return to the country and are able to start building up different political programs and projects for the future.

This is a long term process. It’s not going to happen overnight, but the groundwork really starts now.

MB: When Bashar al-Assad took over from his father in 2000, Syria’s economic situation worsened because of the increasing neoliberalization of the economy which concentrated wealth in the hands of Assad and his cronies.

Whichever authority does end up governing Syria over the long term will, of course, be looking to rebuild this very broken economy and infrastructure. How can people on the left, both within and outside of Syria, challenge further neoliberal restructuring?

LS: Ahmad al-Sharaa already gave a statement saying that Syria was going to move towards a free market economy, and that worried me, because I don’t think it’s their place as a transitional government to start putting forward an economic program. Having said that, the reality is whoever takes over governance is going to be following a neoliberal economic model, because that’s the global paradigm that everyone’s working within, and because of the need for reconstruction and development aid to rebuild the country.

The main concern is dismantling the corruption that existed under the Assad regime. The revolution started in Syria—everyone knows about the political demands, but it started as a revolution for social justice as well, because economic power was so concentrated in a small hand of loyalists and people related to the the president, who totally milked the country and created enormous amounts of wealth for themselves while everybody else was impoverished.

I hope whoever comes after—and whatever economic program is coming—that there will be a lot of focus by Syrians that this doesn’t happen again, and that wealth is much more equitably distributed among the population. But again, only time will tell what kind of economic programs are going to be put forward, and there needs to be a lot of work done on that.

MB: I get the sense that you’re cautiously optimistic about the future of Syria.

LS: I don’t think it’s going to be smooth sailing. There’s a lot of challenges coming up, and we’re entering a new phase of struggle, and a new phase of work to try to build the kind of Syria that people originally went out on the streets for in 2011. I’m hopeful that mass atrocities and that level of absolutely unimaginable violence is a thing of the past. Moving forward to an equitable, democratic, inclusive system is some way off still. But I’m hopeful that the worst of these atrocities have ended.

We’re seeing now so many new initiatives started. I feel like it’s really the early days of the Arab Spring. My inbox and my phone and my chat groups are just flooded with people full of ideas, and people going back to Syria, and initiatives starting. It’s a very exciting time, and it’s up to us to get into that process and see what speaks to us, what’s interesting for us. What can we support? Where can we help with things? And where can we learn from experience and start engaging with social struggles and social movements? That’s all we can do at the end of the day: support our people.

I’m from a progressive, left background, and those people in Syria were the people most abandoned; Islamists went to help out their comrades. Liberals gave rhetorical support—if not real, practical support. But leftists were largely abandoned. We can change that now.

Syria After Assad

Interview with Leila al-Shami

by Sacha Ismail for New Politics

Winter 2025 (Vol. XX No. 2, Whole Number 78) (original post)

The most important thing is maintaining a democratic space where people return and start organizing long term. As long as that space exists, we can push towards a more democratic system in Syria.

Leila al-Shami: The overthrow of Assad was certainly not how I expected 2024 to end. Syrians have been fighting this regime for so long; its end opens up many possibilities that didn’t seem to exist a month ago. There are many difficulties and challenges—but the fact that the genocidal regime has ended, its prisons have been liberated, and Syrians who have been displaced all over the world can go back and start to organize is immensely positive.

Sacha Ismail: Have many people gone back yet?

LS: Yes, a significant number already. But it should also be registered that many refugees can’t currently go back. Many of my friends in Europe desperately want to be in Syria right now, but they’re also very worried about losing their residency status in the countries they’re in.

We don’t know how stable the next period is going to be; there could be new outbreaks of violence, or remnants of the old regime trying to destabilize things. Even though Syrians have kicked out Iran and Russia, there are still foreign states involved, with Israel expanding in the south and conflict in the north between Kurdish-led forces and Turkish proxies. On top of that, the economy is destroyed, many people’s houses no longer exist—so it’s not always clear what they’re going back to.

We need to find ways to put pressure on European states to create mechanisms for people to return and contribute to rebuilding the country without losing the possibility of getting out again if they need to. In fact, the first announcements from European Union states were not anything about aiding the struggle for justice in Syria or supporting reconstruction, but instead suspending asylum claims!

SI: Assad’s fall is a blow for freedom—but the regime was overthrown by groups that are a very long way from the democratic grassroots movements of the early period of the struggle, after 2011. Given the reactionary and authoritarian politics of HTS [Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham] and similar groups, how do you analyze what’s going on? How do we defend and expand “democratic space” in Syria, as you put it in a recent article?

LS: It’s not quite right to say Assad was brought down solely by HTS. What’s happened is the culmination of thirteen years of struggle; that shouldn’t be erased. HTS seized on an opportunity; I actually don’t think they were expecting to overthrow the regime, only a much more limited operation in the north of the country—but they were surprised by how quickly regime forces fled without a fight. Even just on a military level, it wasn’t solely HTS; there were other forces involved in these battles, in Homs, for instance, and in the south of the country.

Moreover, I don’t think everyone fighting with HTS is necessarily ideologically aligned with them. People tend to go where there are opportunities, where there’s money, and where there are weapons. Many of those liberating particular cities were people who had previously been displaced from them. There’s lots of videos of young men talking about being driven out of their homes when they were teenagers, over a decade ago, and now they’re returning.

I’d say there was broad participation, and even some elements of renewed popular uprising against the regime. However, it’s true we now have a situation where HTS is in power in the transitional government, and that’s of concern given where they’ve come from, with their roots in Al-Qaeda and the jihadi movement, and what they represent even now. Their rule in Idlib was certainly authoritarian. In the past they carried out sectarian attacks against minorities, and they cracked down on democratic voices.

Now they do seem to be trying hard to reach out to minority communities, and they say the new system of governance will be shaped with broad input from across society, not just imposed by them. The evidence so far suggests this new regime is surprisingly responsive to popular pressure. For instance, after there were protests against regressive changes they wanted to make to the school curriculum, they retreated and said they’ll only remove its Ba’athist elements, glorification of the old regime, and so on. In Idlib as well, they shifted how they governed in response to public pressure and moderated over time.

I always believed the phase after Assad fell would be extremely difficult. There isn’t an organized democratic opposition that has big influence on the ground. The most important thing is maintaining a democratic space where people return and start organizing long term. As long as that space exists, we can push towards a more democratic system in Syria.

For that reason, I’m actually pleased they’re not going to hold elections for four years. If elections were held tomorrow, it would likely mean a landslide for HTS, because they’re the most organized force in the country, and because they’re currently idolized for their role in overthrowing Assad. More time allows the possibility for other currents to organize and build themselves up.

SI: Is that a consensual view among democratic and left activists? Or do some take the view that four years gives HTS time to entrench themselves?

LS: You’re right, a lot of people are arguing that. It is a possibility that HTS will entrench its power. In my view, however, some are a bit unrealistic in thinking there’s an alternative at the moment. Alternatives still have to be built.

SI: What’s the process for creating a constitution?

LS: There was meant to be a national dialogue conference in January; it has now been postponed. We’re all looking to see how broad and participatory that will really be, how inclusive it is of women, of minority groups, of civil society, even of the political opposition leadership in exile—which doesn’t have mass support on the ground but does include important figures who need to be involved if we’re going to have a real pluralism of voices. At the moment we don’t know how the conference will be constituted. It’s something that civil society groups and gatherings in Syria are discussing.

You don’t need four years to create a constitution. The opposition in exile did a lot of work on this question, and in any case the issues with the old constitution were not necessarily its specifics but the fact it was a farce that didn’t really affect how Syria was governed. For me the question of the constitution is much less important than the question about democratic space for organizing, and whether there’s a vibrant civil society—but of course people have a range of opinions on that.

SI: Who are the exile opposition leaders you refer to?

LS: There’s the Syrian National Coalition, which was based in Turkey for years. They were originally set up to do international negotiations on behalf of revolutionary Syrians, to gain international support, money, weapons, and so on. They were a coalition of different political persuasions—some liberal, some Muslim Brotherhood types, some leftists, and some of the Kurdish parties. Over time they became so distant from what was happening on the ground that they became the butt of Syrian jokes—negotiating in five-star hotels in discussions that went nowhere, at times accused of corruption and being beholden to foreign powers.

They became irrelevant: later on, there were negotiations between the various regional powers intervening in Syria, and they weren’t even invited. There are significant figures involved, though, with a great deal of political experience, who need to be involved in the transition process.

SI: What democratic struggles on the ground would you flag as most important?

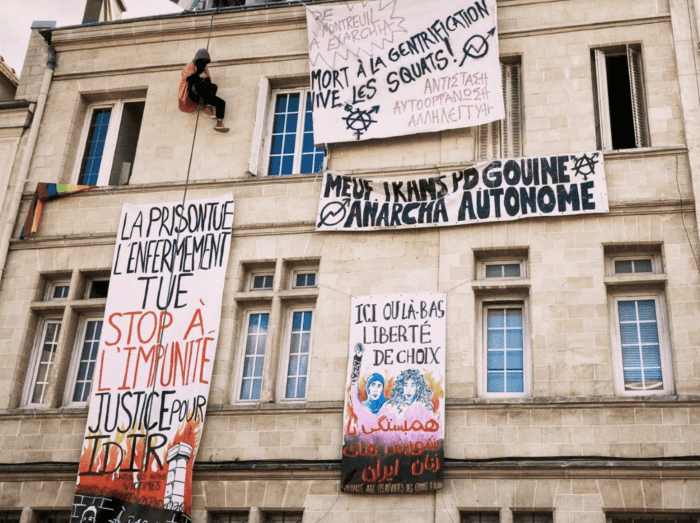

LS: Lots of things are starting up, and our focus over the coming period should be finding out more about what is being done on the ground and how we can support it. There is already vocal agitation by women’s organizations, groups calling for women to be included in the transitional process and for their rights to be respected by the new government—and similar agitation from a range of minority communities.

People are calling for justice and accountability. Organizations dedicated to prisoners’ rights and to state accountability have been working with the families of prisoners and the dead or disappeared to address this in a number of ways. One aspect is about protecting or recovering evidence, some of which has been destroyed or not properly safeguarded by the authorities. It needs to be collected and given to organizations that will preserve and protect it, so families and loved ones have clarity about what happened to people, and to ensure accountability of those who have committed war crimes.

This is not only a matter of those imprisoned, killed, or disappeared by the Assad regime. The regime was responsible for the overwhelming majority of civilian deaths, but other factions have also committed crimes. Since Assad’s fall, there have been demonstrations specifically about the disappearance of the Douma Four, democracy activists and human rights defenders who were likely taken by the Islamist opposition group Jaysh al-Islam. And what about those imprisoned by HTS, whose families have protested for their release, in Idlib and Aleppo?

SI: What about workers organizing? What are signs this is beginning to happen, or that there are discussions about it? I did read a report that mentioned a strike by firefighters in Damascus in protest at a decision of the new government, and about lawyers organizing. However, I assume the conditions are difficult.

LS: There are a number of factors that mean workers’ organization is starting from a very low base. One is the structure of the economy in Syria. Most of the economy is based on small, family-run businesses, with all that implies for collective organizing. A second is the co-option by the Ba’ath Party, over decades, of any independent workers’ organization: unions were effectively destroyed and replaced by—or transformed into—parastatal organizations over which workers had no control. This is the experience that generations of workers had of “trade unions.” This meant that the bigger-scale, largely state-run sections of the economy were hostile ground for organizing too.

In the early days of the revolution, after 2011 and maybe up to 2014, new independent trade unions were set up in various sectors and parts of the country—the Union of Free Syrian Students, the Union of Free Syrian Doctors, and so on—and became quite significant. However, in the last decade the conditions for such organizing have become much less favorable, and I’ve heard much less of these unions. I hope there will be renewed efforts in this direction.

SI: Am I right that socialism as an idea is widely discredited in Syria because of its association with the old regime, as well as the general political conditions in the world?

LS: Absolutely. It’s a problem that, to the end, the Ba’athist regime presented itself as “socialist.” But another factor is the bad response of wide swathes of the left globally to the Syrian revolution, which has created a lot of animosity toward leftists, and by extension any kind of socialist project. That’s not to say there aren’t many leftist Syrians, but the terrain on which they are now organizing is not favorable. Even I, as a leftist who works with many amazing leftists all over the world, feel this: my first reaction if I meet a leftwinger is to fear they are an Assad apologist.

It can’t be overemphasized how distant from—in fact, radically opposed to—anything like socialism state ownership in Syria has been. It was always intertwined with a system of crony capitalism, benefiting the Assad family and their clients—many of them Alawis, but also a layer of Sunni businessmen who constituted an important part of the regime’s support. Then progressively, within the state-dominated system, more neoliberal elements were introduced. Crucially subsidies that millions of Syrians relied on were progressively removed. This kind of policy accelerated after Bashar Al-Assad came to power [in 2000], and by 2011 poverty and unemployment were chronic and wages were low.

I remember this very vividly from when I was living in Syria. Many people worked two or more jobs to provide for their families. Of course this was also a factor in the protest movement beginning.

SI: What are the debates now about different programs for economic reconstruction? Is the automatic trajectory more neoliberalism?

LS: Ahmed al-Sharaa has already said there will be a move to a more free-market economy. As on many issues, I don’t think it’s his place to say that; this is supposed to be a transitional government, and such vital questions need to be decided through a process with real participation and debate. However, to be honest I think anyone likely to come to power is going to promote a free-market economy. There needs to be discussion about shaping the specifics of what that looks like, about how widely the mass of Syrians benefit from reconstruction. The starting point of that is, again, about popular organizing at the grassroots, including by workers.

Immediately there is an issue about lack of international support for rebuilding the economy. The German foreign minister has just been in Syria and indicated there will be no substantial aid provided unless the transitional government meets a series of conditions; meanwhile the Americans have said they are not removing sanctions—in fact they’ve extended them for five years.

This is obviously hugely detrimental to reconstruction, but also to democracy in Syria. If the West continues to boycott Syria, the dominant players will be the Gulf states, who care much less about promoting any elements of democracy or inclusivity as a condition of aid.

Much of the Western left campaigned to remove sanctions on the Assad regime. So what will they say now? It’s something the better sections of the Western left should take up.

SI: Does the old regime have significant residual report?

LS: Yes, it has some. In late December there was a protest in Damascus for a secular state and, unfortunately, quite a number of well-known regime supporters were involved in organizing it. There weren’t many revolutionary flags in the crowd, though there were some. This was potentially a setback for secularism, a danger that—as with socialism—it becomes associated with the counter-revolutionary cause.

Some of the former regime supporters genuinely fear Islamism, but there is also a strong element of potentially losing their privileged position in society now that Assad is gone.

The other noteworthy element is all the warlords and so on, on various sides, who have benefited from the war economy and therefore have an interest in seeing Syria destabilized so that conflicts continue.

However, I believe the overwhelming majority of Syrians, whether pro-revolution or pro-the-former-regime, have an interest in seeing the country return to some kind of normality and a stable situation. People want a functioning economy and a functioning country, and I think that greatly strengthens resistance to attempts to prolong or regenerate armed conflict, and hopefully can override them.

SI: What’s your assessment of attempts to fan sectarianism on various sides?

LS: I’ve been struck that so far there hasn’t been a mass outbreak of intercommunal, sectarian violence. We’re seeing isolated incidents that are undoubtedly being fanned and stoked by various actors to spread fear in communities and provoke violence. There’s a lot of misinformation being circulated—for instance when the killing of former regime army officers and torturers is presented as persecution of Alawis.

We shouldn’t support random killings, we should support a legal process of justice and accountability, but it’s a different matter from sectarian persecution. The flip side is that ensuring justice and accountability for the crimes of the old regime will help prevent wider outbreaks of sectarianism, and reassure minority communities that they are not a target. To be fair, the HTS leadership at least seems genuinely very concerned to try to prevent sectarian conflict.

SI: The Kurdish question is obviously very important. How do you see it?

LS: It is undoubtedly a main flash point. The so-called Syrian National Army is really working to Turkey’s agenda, which is to put an end to any claim of Kurdish autonomy in the north. More broadly, though, there are not many Arab voices speaking out in defense of the Kurds. Some of this is Arab chauvinism or nationalism, which was promoted by the Arab-dominated Ba’athist regime. In the early days of the revolution, the Syrian National Coalition alienated the Kurdish population by refusing to even consider Kurdish autonomy. HTS have made some reasonable statements to reassure Kurdish communities, but at the same time they’ve failed to call out the Syrian National Army for the abuses and atrocities it is carrying out against Kurds.

Opposition to the Kurdish project is not all because of Arab chauvinism though. Some of it is political: for example, the perception that Kurdish-led forces at times collaborated with the Assad regime. There is also a genuine problem that over years the SDF [Syrian Democratic Forces] pushed its control well beyond the areas where Kurds have a clear majority and clamped down on any opposition. It created a system of rule that many found preferable to the Assad regime and ISIS, at the time when there weren’t other alternatives—but now these communities would rather be governed by the transitional government. There have been protests against the SDF, and some people arrested and shot, in Raqqa and other areas.

There are some difficult issues here. However, I’ve always supported Kurdish autonomy and I continue to support it. All communities should play a role in the future of Syria, in accordance with the specific needs and aspirations of each community. I believe a decentralized system could be the model which can ensure unity and stability long term.

SI: What do you think about the view that exists among some on the left globally that Rojava is an anarchist paradise or something like that?

LS: Western leftists sometimes like slogans more than reality. In reality it’s a mixed bag.

A lot of what has been done in the Kurdish areas is genuinely progressive—notably women’s participation in political life and elevation to leadership positions, which is something I would wish to see all over Syria. There is also a genuine element of multi-ethnic political representation and governance, although you can question whether that would not also have existed in some form even without the specific PYD [Democratic Union Party] political project. In areas with mixed communities, people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds participated in local governance throughout the revolution. In Manbij, for instance, before SDF rule, the local council was already both Arab and Kurdish.

But the idea that the PYD is an anti-authoritarian, libertarian force is misguided. They have clamped down on opposition in the areas they run—not only Arab opposition but Kurdish opposition too. When I was in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2016, I came across a lot of young Syrian Kurdish men fleeing forced conscription by the PYD. There’s a lot of people imprisoned in the SDF-run areas, and in recent weeks a significant number of arrests. That is not just a matter of jihadists or people supporting the Turkish agenda. There are communities with understandable grievances.

On the other hand, you can see why Kurdish people and SDF leaders feel under siege and are highly distrustful. Like the Druze in the south, they’re now being told to give up their weapons to a new Syrian army. I think it would be a mistake for them to do that without some real guarantees. In any case, it is a priority to speak out against the Turkish-backed forces and the atrocities they are committing. This risks sparking wider inter-ethnic conflict and is an obstacle to future stability

SI: The British media talks quite a lot about ISIS, for obvious reasons. Is it a real issue now?

LS: I think it is a real issue. There could be a resurgence. There are reports from eastern and southern Syria (though I don’t know how accurate they are) of ISIS remnants capturing regime army caches. We need to look into this.

The Kurdish-led SDF fought ISIS, of course, but so did various Arab (including Sunni) groups—including, in fact, HTS. One problem now is that after the fall of the regime Israel destroyed large amounts of Syrian government weaponry and military equipment, putting the new government in a much weaker position in this regard. Meanwhile, if the US withdraws its support for the SDF that could add to the ISIS problem.

SI: If the left wants all foreign military forces out of Syria, how do we address that dilemma in terms of US support for the Kurds, which Trump may well withdraw for malign reasons?

LS: I don’t know that I have much I can add, except to say it is a dilemma. In general we should favor the withdrawal of foreign forces from Syria, but this requires real assurances being provided for the Kurdish community that their rights will be respected.

SI: Can you say a bit more about the intervention of outside powers?

To start with Iran, lots of their military infrastructure in Syria has been completely decimated by Israel, and what’s left has been pulled out, so militarily they’re no longer a presence or a problem. Where many think they are still playing a role is in the spreading of sectarian propaganda, coordinated in an organized way from inside Iran.

Russia I’m less clear on now. They’ve done a partial pull-out, but they seem to still be present in the bases in the west of the country. Clearly they’re having discussions with HTS, but beyond that it’s unclear.

The main worries at the moment are Israel and Turkey, which are extremely active and aggressive in the south and north of the country.

SI: And how could the upheaval in Syria influence other countries?

LS: I tweeted in the first couple of days after the regime falling that people in the countries of the Arab Spring who have faced vicious counter-revolution might now be looking to Syria with some kind of hope. It shows that there is hope, that both domestic and foreign oppressors can be defeated. We will see if it leads to a revival of people’s struggles in some of those countries.

Syria was always presented throughout the region as the bogeyman: If you protest against your government you’re going to end up like Syria, you’re going to be completely destroyed. However, there’s light at the end of the tunnel, it turns out. Maybe that will help revive some activism in the region.

Many people in Lebanon will of course welcome the fall of a regime that previously lorded over their country too. It is hard to know what it will mean for Hezbollah, who have their own problems after being so battered by Israeli attacks. Their murderous intervention in Syria in support of Assad—continuing in force even at times when Israel was invading Lebanon—was not popular among many at home.

SI: You’ve flagged the failings of the Western left on Syria. Can you unpack this further?

LS: The basic issue is that large parts of the Western left focus only on US and Western imperialist powers, leading them to apologize for or support other imperialists, such as Russia—or, in the case of Syria, Iran. Even worse, this means in many cases not supporting people’s struggles against oppression, whether that’s domestic oppressors or foreign imperialisms. This is a huge problem that is bigger than Syria, bigger than Ukraine: we see it playing out in many other struggles. Hong Kong is one that immediately comes to mind. By the way, this is why so many Syrians at all levels of society enthusiastically support Ukraine, which has been beautiful to see.

Campism is a very regressive and dangerous ideology that is destroying the Western left internationally at just the time we need to be building our strength and unity against rising fascism and authoritarianism, against the climate crisis, and against increasing conflict. We’re not in a place to do that because of these reactionary “left” actors whose politics have little connection to struggles happening in the real world.

In the case of the Syrian revolution, many Western leftists did everything they could to defend the Assad regime and malign and slander the Syrian opposition, calling them all jihadists, or CIA-backed, or agents of Israel—that one’s very popular at the moment—and all the rest of it.

SI: There’s an irony that many of the same leftists are, in other contexts, uncritical or supportive of Islamism.

LS: It depends which Islamists. Syrian democrats were slandered as Islamists and presented as something to fear, but then the same leftwingers have no problem with Hezbollah or Hamas. It’s campism again: you don’t analyze the forces on the ground, it’s really only who they’re resisting that matters. If it’s Israel and the United States, leftists are supportive, no matter who’s fighting them; but if it’s another camp, they take a very different view.

I should stress that most of the Westerners I’ve worked with in support of Syrian struggles are leftists. There is still a strong strand of the left who believe in internationalism from below and have a decent analysis. I also think the invasion of Ukraine did force some people to reassess Syria, through the channel of Russia’s role in both. I would also question whether there was an element of not having such negative stereotypes about white Europeans. In any case there was some positive reassessment.

Nonetheless, the dominant organized left has been terrible. The main so-called antiwar organizations in the UK and in the US have in one way or another supported brutally repressive regimes against the wishes of the local populations, including in Syria. That’s also true of leading political figures on the left, and also of prominent leftwing intellectuals. It’s a long history too—it goes back to Bosnia in the 1990s and even before that.

Since the Assad regime fell, many of its apologists are trying to rehabilitate themselves as legitimate critics, with concerns about the rights of minorities and so on. We need to highlight the role they’ve played, because these people will never be allies in liberation struggles.

SI: Last but not least, what practical solidarity is needed?

LS: In terms of internationalist calls, we should call for all foreign militias to leave Syria. We should call for an end to sanctions on Syria so that Syrians can go forward with the rehabilitation and reconstruction they desperately need. There’s also a role for international justice and accountability mechanisms for people accused of war crimes—primarily regime people, but also from other factions that committed war crimes. Related to this, we need to support people fighting for transparency and documentation relating to prisoners and the killed and disappeared.

Beyond that, it’s a matter of identifying who on the ground is organizing what struggles for peace, for democracy, for women’s and minority rights, and for social justice, and providing as much political and practical solidarity as we can. In the coming months it will become much clearer who those groups and individuals are.