Transcribed from the online event “Rediscovering a History of Jewish Anarchism” hosted by Firestorm Books (Asheville, North Carolina, USA) and printed with permission. Watch the whole conversation:

For so long, Jewish anarchism has not been a focus of Jewish history, or even of Jewish leftist history or the Jewish labor movement. You’ll find a lot of great books that will actually carve anarchists out of the story, so bringing that back in is fantastic.

Libertie: Welcome everybody, thanks so much for joining us.

My name is Libertie, and I am a member of the Firestorm Collective. This evening we’re excited to be hosting Kenyon Zimmer, alongside authors Anna Elena Torres and Shane Burley, for a discussion of Joseph Cohen’s 1945 Yiddish-language history of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States, an awesome tome just recently put out by our friends at AK Press.

Firestorm is a sixteen-year-old radical bookstore owned and operated by a queer feminist collective in southern Appalachia, on the land of the Cherokee people. We strive to feature books and events that reflect our interests, and also the needs of marginalized communities in the South. We are continuing to do virtual events like this one as often as possible, because we know that it both gives us opportunities to connect with folks at a distance, and also because we know that even here in our own community, there’s a lot of folks for whom in-person events face a lot of barriers.

I’ll get started by introducing the folks who are with us tonight. First up we have Kenyon Zimmer, who is an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is the author of Immigrants Against the State: Yiddish and Italian Anarchism in America, and co-editor of Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW, Deportation in the Americas: Histories of Exclusion and Resistance, and With Freedom in Our Ears: Histories of Jewish Anarchism.

Kenyon is here rocking a very awesome Firestorm shirt. Great to see you again, Kenyon.

It wasn’t in the bio I just read, but Kenyon edited this new edition of The Jewish Anarchist Movement in America, the cause for the gathering tonight.

Next up I want to thank Anna Elena Torres, who is an assistant professor in the department of comparative literature and race, diaspora, and indigeneity at the University of Chicago. Torres is the author of Horizons Blossom, Borders Vanish: Anarchism and Yiddish Literature and co-editor of With Freedom in Our Ears. Torres’s publications include work in Prooftexts, Jewish Quarterly Review, Nashim, make/shift: A Journal of Feminisms in Motion, In Geveb, and ArtsEverywhere. Torres’s creative practice has included work as a poet and translator, community arts organizer, muralist, and conceptual artist.

Really appreciate you being here tonight, Anna.

Last but not least, we’ve got Shane Burley, who is a journalist based in Portland, Oregon. He’s the co-author and editor of four books, most recently including Safety Through Solidarity: A Radical Guide to Fighting Antisemitism (which we had the pleasure of hosting a fantastic virtual event around). Shane’s work has been featured in such places as NBC News, The Baffler, Al Jazeera, Jewish Currents, In These Times, Newlines, YES! Magazine, MSNBC, Oregon Historical Quarterly, and I’m sure several more.

Thank you so much for being here with us, Shane.

I’m going to get out of the way and pass it off to Kenyon, who I know has prepared an introduction to the book. We’ve got a lively conversation ahead, so buckle your seatbelts, folks, and thanks for being here.

Kenyon Zimmer: Thank you so much.

Thank you all for joining us. This is amazing. I want to give a shout out to Firestorm Books, it’s an amazing place—I was there this past summer. It’s an incredible store and an incredible community. They have incredible t-shirts as well.

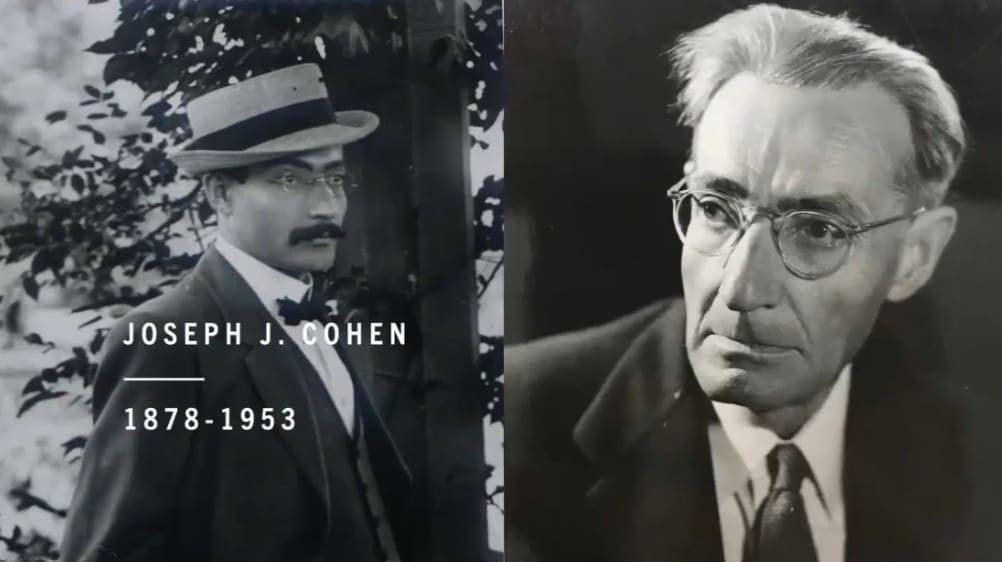

I’m going to give you the very brief history of this history by Joseph Cohen. This first picture of Joseph Cohen is from around the time of his immigration to the United States in 1903; the other photo is him around 1945, the time of publication of this history that he wrote.

Cohen was born and raised in eastern Europe and part of the former Russian empire and had a rather typical Jewish religious upbringing. He was quite smart, was well-educated, became radicalized as a young man, and came to the United States in 1903 with his wife Sophie Cohen (who plays a part in the book as well)—and immediately, both he and Sophie became deeply involved in the anarchist movement, initially in Philadelphia, where they lived for a good portion of their time in the United States.

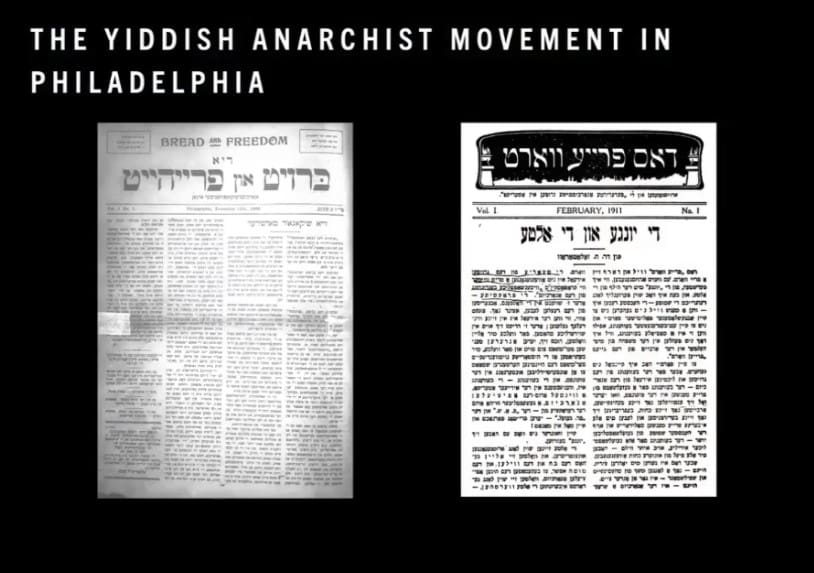

Here are two different anarchist newspapers published out of Philadelphia that Cohen was involved in.

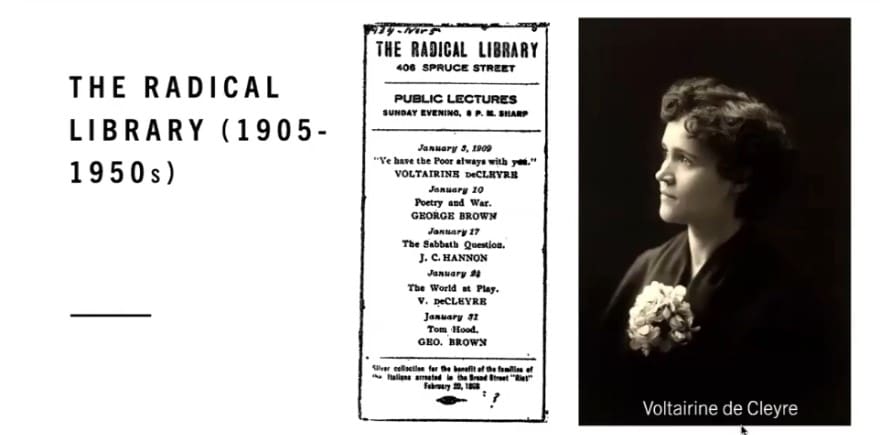

Cohen was one of the major co-founders and people responsible for running the Radical Library of Philadelphia, which today we might call an anarchist infoshop. It was a library of radical literature as well as an event space, a place where classes were held, speeches were held, performances, fundraisers, all those sorts of things.

In Philadelphia, both Joseph and Sophie Cohen were tutored in English by the anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre, who became a very close personal friend, as one of the more prominent non-Jewish anarchists in Philadelphia at the time.

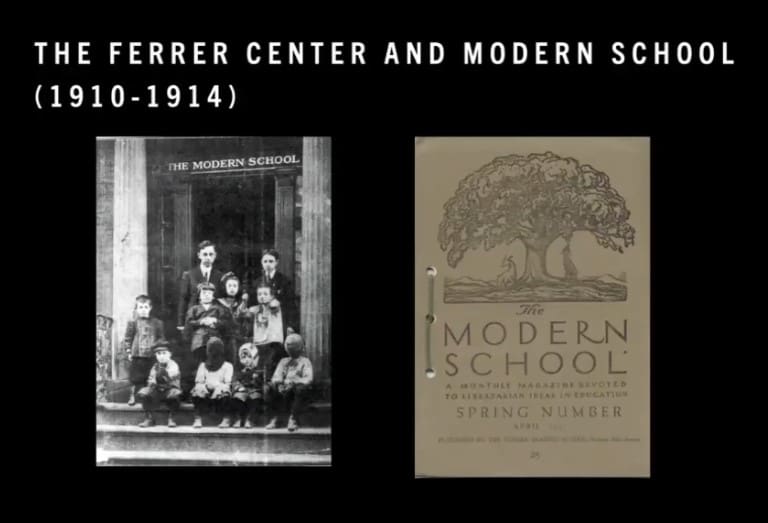

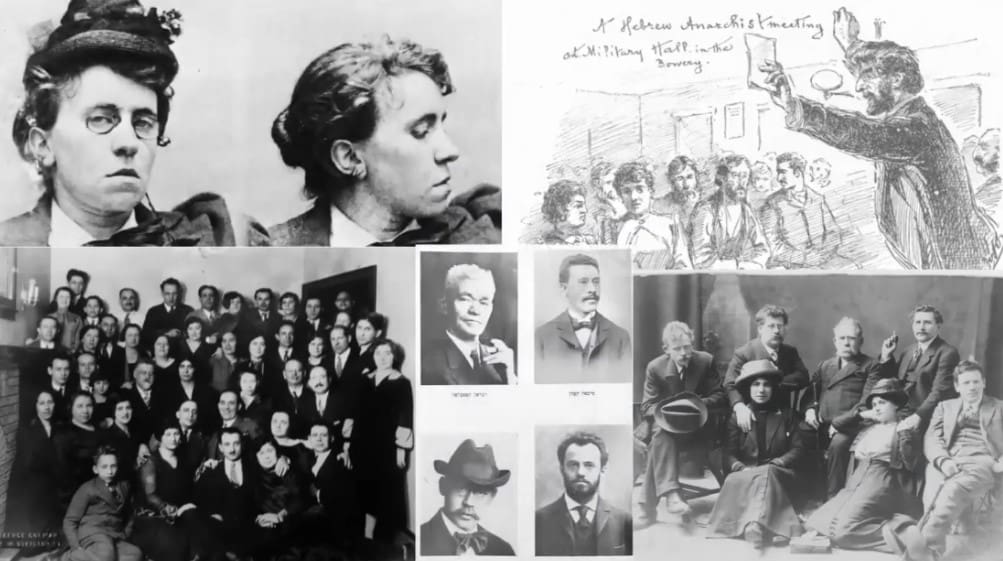

Joseph Cohen went on to be the caretaker of the Ferrer Center and Modern School in New York City, initially in Harlem. This was an anarchist educational experiment co-founded by Emma Goldman among many others. Cohen was responsible for the facility for several years before the school moved to nearby Stelton, New Jersey, in a rural area where an intentional community of anarchists was built around the relocated school that became known as the Stelton Colony.

Cohen was one of the founding members and major players in the Stelton Colony for its initial period. The colony itself lasted all the way into the 1950s. Cohen was also one of the major movers behind the formation of Jewish Anarchist Federation of America and Canada, which formed in 1921 and lasted into the 1970s. He was also the primary author of the Jewish Anarchist Federation’s manifesto, which is included in the book as an appendix, as it was in the original Yiddish.

He then went on, in New York City, to become editor of the most important and largest-circulating not just Yiddish anarchist newspaper but any anarchist newspaper in the United States, the Fraye Arbeter Shtime [Free Voice of Labor], which he edited from 1923 to 1932, putting him right at the center of the global Jewish anarchist movement, and at the center of New York’s Jewish labor movement and Jewish left in general.

From there, after leaving the editorship, he was one of the organizers of the Sunrise Co-operative Farm and Community in Alicia, Michigan, which is about an hour away from Detroit. This was a Depression-era, primarily Jewish, primarily anarchist attempt at creating a self-sufficient agricultural commune that had significantly more problems than the Stelton Colony. There’s a chapter dedicated to it in The Jewish Anarchist Movement in America, but in addition Cohen wrote an entire other book just about that experience, called In Quest of Heaven, which was published in English.

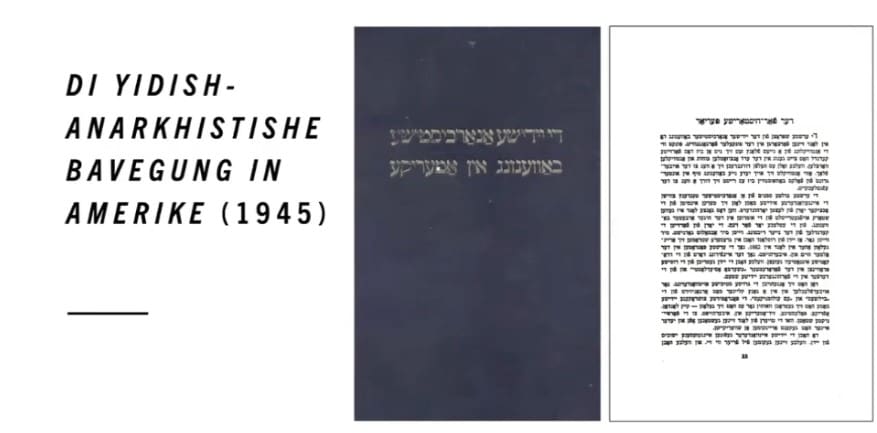

In 1945, he published this book in its original Yiddish version, Di Yidish-Anarkhistishe Bavegung in Amerike. He was initially asked if he would consider writing a history of the radical library in Philadelphia, and then he immediately decided he couldn’t possibly do that story justice without telling the entire history of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States. This was the result of that: of several years of intensive research, informal oral histories with veterans of the movement, his own personal participant observations and experiences, and so on.

It remains to this day the only book-length study of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States, which is one of the reasons it’s so important that it’s finally available in English. The core of this book and its importance is summed up in this quote in the introduction by Cohen:

Our comrades did not write history, they made history. Few of our comrades even found it necessary to pen personal memoirs. The work of systematically recording events they left to other, often hostile, elements [which you should read as Marxist elements] who ignored our contributions, often maliciously misrepresenting them, trying to give the impression that we simply disrupted others’ work, tilting at windmills, and contributing nothing constructive ourselves.

What this book does is focus on both the prominent individuals and activists—Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Rudolph Rocker—but also and especially Jewish anarchists’ role in the labor movement, their role in Yiddish culture, and gives as much attention as he can to the rank-and-file activists involved in all of this. Not just in Philadelphia and New York, but in cities all across North America as well as in England. He really felt a responsibility to try to highlight and give credit to as many of these activists as possible.

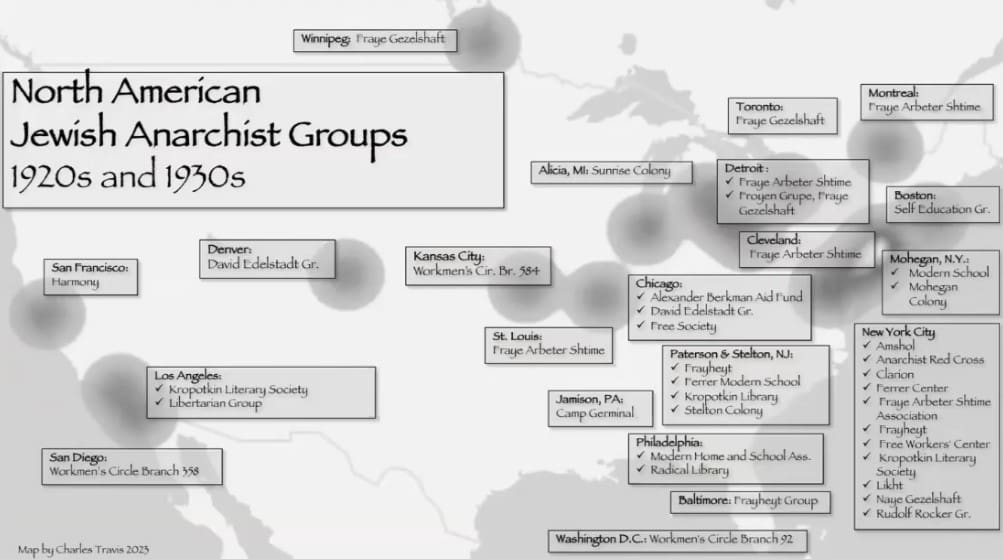

Just to give a brief feel for the extent of this movement, this is an image that I commissioned for this edition of the book, showing the extent of Jewish or primarily-Jewish anarchist groups throughout North America in the 1920s and 1930s—so after the real height and heyday of the movement, but continuing strong into these decades when the anarchist movement in general is virtually ignored in most histories.

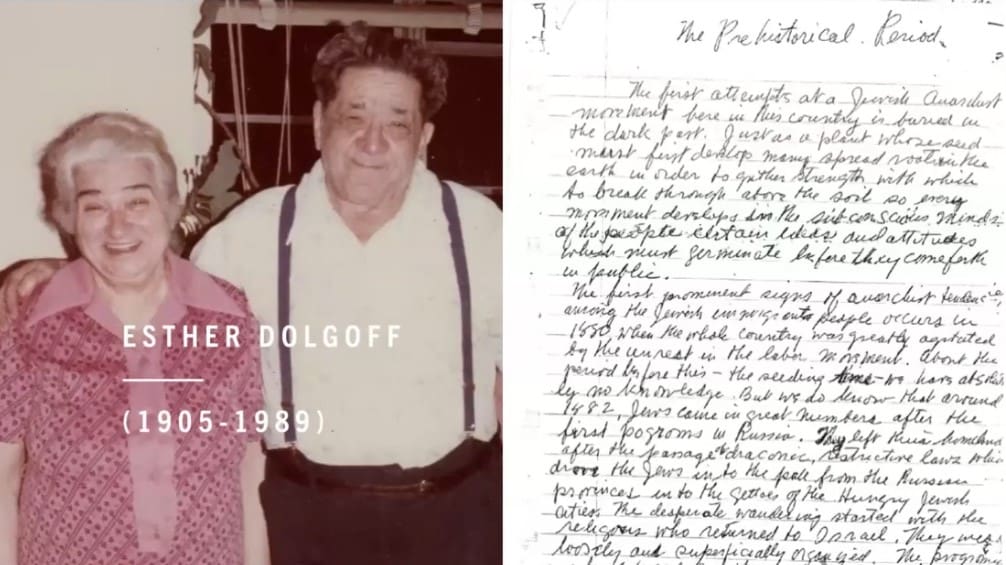

The book was published in Yiddish in 1945 to mixed reviews, for reasons I get into in my introduction to this edition. It was translated into English in the late seventies by Esther Dolgoff. Esther Dolgoff was married to Sam Dolgoff—they were both prominent anarchist activists in the mid-twentieth century United States; they both knew Joseph Cohen. They had overlapped with him at the Stelton Colony, in fact. And Esther admired this book as the one-of-a-kind, irreplaceable history that it is. In the late seventies she went about beginning to translate it by hand into English. The result is more than eight hundred handwritten pages of translation, which form the basis of this new edition.

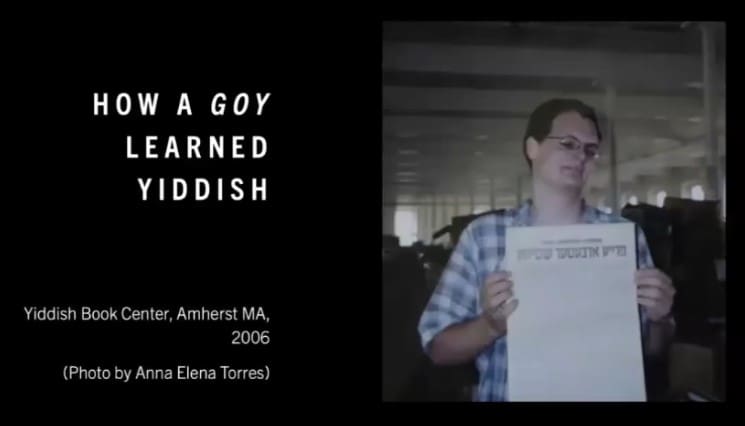

She passed away in 1989 without finding a publisher for this book—which leads to me. I, as a graduate student in history, studying the history of anarchism in the United States, went about learning Yiddish as part of that process. I did an intensive Yiddish summer program at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. You can see me here, with more hair than I have now, holding up a copy of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, in a picture that Anna actually took. We first met as students at the same summer program back almost twenty years ago.

I was very much interested in the largely-untold history of Yiddish-speaking anarchists in Cohen’s book in particular, which I first encountered in its handwritten translation form, and then at the Yiddish Book Center got my hands on the Yiddish edition, and learned to read it and other Yiddish sources, and had long entertained the idea of producing some sort of edited and annotated version for modern readers—but it always seemed like an impossibly difficult and time-consuming task.

Then, years later, I received an email out of the blue—on December 28, 2017, from someone I’d never heard of named Eric Gordon, who asked if I could talk with him about a project involving a translation from Yiddish to English, a book about the anarchist movement. I immediately suspected he was talking about Esther Dolgoff’s translation, which in fact he was. It turns out Gordon was a friend of the Dolgoffs in the seventies and eighties, and had been asked by Esther to try to find a publisher for her translation.

He had, among other things, commissioned the text to be typed into a word processor, but that’s essentially as far as the project got under his watch, due to difficulties in finding a publisher, finding time, and so on, and the fact that a lot of the text is like this—just a list of names that don’t generally mean much to a modern reader.

So I lucked into inheriting the transcribed copy of Dolgoff’s translation, and spent several years, on and off, trying to figure out who all of these names are, and then annotating the text with more than seven hundred of these biographical snippets, with the information that I could find on the hundreds of individuals named by Cohen throughout the book.

The thing that really made this possible, after a lot of time spent (and time spent procrastinating), was just a few years ago the full run of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime became digitized and fully text-searchable, as the software necessary for doing that with the Hebrew alphabet only very recently came to be. This allowed me to look up obituaries and look up people’s contributions to the Fraye Arbeter Shtime over an eighty-year period. This was the main source I used for reconstructing biographies, in addition to census information (also digitized) and way too many other sources to name.

The result was, I finally had the tools that made it feasible to go about annotating Cohen’s text—a three- or four-generation process from Cohen to Esther Dolgoff to Eric Gordon to me, which also came with an almost crushing sense of responsibility to get this right—though I truly hope I have done this project justice, and it brings me immense joy to see this book out in the world, available to readers who maybe can’t read Yiddish.

That’s the very quick intro to the project and its own history, and we have some questions to bounce about ourselves now.

Anna Elena Torres: I can ask the first question, but first of all I want to say thank you to Kenyon for your incredible labor to bring this to a wider audience. When I was a graduate student, Kenyon actually shared with me the facsimile of the eight-hundred page handwritten photocopy-of-a-photocopy of the translation, which was my first encounter with this text. I think I speak for many people who will be grateful that that will not be the way they are reading this as well. That’s in addition to your incredible, painstaking work to track down these people’s lives and include them in the history.

Speaking of this biographical aspect, I wanted to ask if you could say a bit about a couple of the people discussed in the book who you found most fascinating, and why. What were their unique contributions?

KZ: It’s a great question, it’s a huge question. There were hundreds of rabbit holes I had to tumble down to assemble this. Exercising some restraint: one of the biographies I found most fascinating in recovering for a footnote—and readers might be able to tell, because it ended up being one of the longest biographical footnotes in there—is of a writer named Louie Levine (and later Louis Lorwin) who is mentioned in passing in Cohen.

His actual story is not really well known, and completely bonkers. He was a Russian Jewish revolutionary who immigrated to the US as a child with his family, then later was educated in Europe; returned to Russia, took part in the 1905 revolution; came back to the US, wrote for the Fraye Arbeter Shtime on anarchist theory and tactics; and then got his PhD at Columbia University, wrote a dissertation about the French syndicalist movement (that is still regarded as an authoritative text), wrote the first history of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union; then changed his name, hid his revolutionary past, and ended up a decade later becoming an advisor in the New Deal and one of the authors of the Marshall Plan, the economic aid package to postwar Europe—all stemming from his interest in economic planning, which stemmed from his interest in syndicalism originally.

It’s a strange, wild path that he took from revolutionary Russian anarchist via syndicalism to planned economies to being a behind-the-scenes important figure in twentieth-century world history. And that’s just one of a million stories that I could tell, but it’s one that I could write a whole book on.

Shane Burley: I want to jump in—I appreciate you letting me come and sit in and talk about this book. I’ve been really inspired; I’ve read this book over the last six months and it’s been a real joy. One of the things that’s so remarkable about it (and about both of your work) is that for so long, Jewish anarchism has not been really a big focus of Jewish history, or even of Jewish leftist history or the Jewish labor movement. You’ll find a lot of great books that will actually carve out anarchists from their story, so bringing that back in is really fantastic.

I’m also curious for your thoughts about how anarchist histories—anarchist memoirs, biographies—are different. How does this strike a different chord than what we often get in history, and what does it contribute to that storytelling of history and recovering of history?

AET: Thanks. I think of anarchist history as written at eye-level, in the sense that you can make eye contact with the people whom you’re reading about, as opposed to hovering over them or seeing them from a great distance. There’s a kind of intimacy to the way people’s lives are recorded, and the dignity and attentiveness to the individual life.

How is that related to anarchist thought? How is this form or genre of anarchist history related to anarchist thought? One aspect of it is how anarchism asks people to reflect continually on their own power and how they relate to the power of others in daily life and their workplace—with your coworkers and your boss—and in your kinship structures. It follows from a philosophy that has a radical attention to power and connection in daily life that anarchist historians would then attend to the daily lives of those who are involved in the movement.

We see this tendency in the work of Paul Avrich, for example—even in the titles of his books: Anarchist Portraits; Anarchist Voices: An Oral History. We see this as well in the work of the contemporary writer Kathy Ferguson, who’s been working on an ongoing project of a mass biography of anarchist women.

Part of Kenyon’s work as well, which I want to hail, is that this process of research is also restorative, reparative to the biographies of women who were not necessarily even mentioned in Cohen’s work but have been added in the notes—or they’ve been mentioned only as the wives of some of these activists. So I think of anarchist history as a practice of anarchist thought as well.

KZ: I don’t know that I have a lot to add to that. We certainly see in Cohen—he’s explicit about this in his introduction. He’s striving to give credit, to name-drop as many contributors to the movement as he can—which is part of the reason the book was viewed as unpublishable for a long time. There were these long lists of names with no context or information about the individuals, even if, as Anna mentioned, he was sometimes more prone to name the male activists in those lists of names.

I think anarchist history is also very much attentive to individual and collective agency, and therefore to historical indeterminacy. Anarchist historians and anarchist history has a lens that usually shies away from strictly materialist explanations, and particularly shies away from any notions of historical inevitability or historical “stages,” those kinds of things.

So let me ask you two, as readers of the book, a question that has come up in the various other talks I’ve given about the book. What lessons can contemporary anarchists or activists take from Cohen’s tale that he relates?

AET: One of the really remarkable aspects of the document is how it records the social life, the sociality, of these anarchists: mutual aid societies, for example, as well as libraries like the Kropotkin Literary Society. It documents the labor that goes into organizing, and it pays a great deal of attention to the process of translation, thinking about the Yiddish radical press not only as an engine for expression but also as a mode of translation in which they’re taking in works of philosophy (for example, there was a serialized translation of Spinoza—I’m sure people were on the edge of their seats waiting for the next week to get to the next installment of a Spinoza translation), thinking about the significance of translation as a social practice, as a way of building their interconnection with the rest of the world, their philosophical engagements, and the commitment to translation as a form of building coalitions and comradeships.

I brought some of those translations today to show folks. Here’s a pamphlet from 1914 which is a translation of Sébastien Faure—this was published in New York. We can think about the role of not just the authors but the role of the translators—certainly Esther Dolgoff herself—and including the names and the labor of translators is also a way to include more women in the writing of this history. Perhaps women were not signing the articles, but they were also involved in the translation and the distribution of them.

I also have a translation of Kropotkin; this was published in 1906 in London—thinking about this interest in connection between the Yiddish- and the Russian- and the English-speaking world, and the French-speaking world.

Here is a work by [Jacob] Maryson, who is discussed at length in Kenyon’s work, as an editor; he was also a translator, of Darwin and a lot of scientific texts. The way these books were being translated showed an anarchist commitment to knowledge and philosophy beyond what we might think of as anarchism itself—towards the pursuit of some larger truth and knowledge.

This is from the 1890s: these are bound copies of Fraye Gezelshaft, and it’s fascinating to look through the ads in the back. You can get a sense of the social life, the cafe societies, the parties, the plays they were seeing, the poetry they were reading. It gives you a snapshot of the social world and the attention to building the world that they wanted to live in, through mutual aid, through direct action, through these literary spaces.

Just to give you a sense of the care with which the typography is done, here’s a photo of the Haymarket memorial in Chicago, where Emma Goldman and Voltairine de Cleyre are also buried—thinking about the spaces that were made possible in order to build up the world.

SB: The question of mutual aid also came to mind. I think the most-referenced organization throughout the book is Workers’ Circle. It was a membership organization that did mutual aid and a number of other things, but that mutual aid—sharing resources, getting people what they need—that was the foundation; that was step one that everything else was built on: the labor movement, the relationships, publications. It really started with getting people those basic needs and building that connection, having a social family life.

This seems really important, and we have that question now, particularly after 2020: what does it mean to have mutual aid networks? And is that now the foundation of doing any kind of organizing?

One thing that’s really striking to me in the book is that it’s not just a secular Jewish identity, it’s a very anti-religious Jewish identity in certain parts, particularly early in the book where they discuss getting into literal fistfights with orthodox leaders, or fighting over what’s going to happen on Yom Kippur and serious holidays. But this evolves a little bit, or at least we see those questions evolve in the text. There’s a really interesting story about one of the communes they’re at, where a person’s father comes: he’s an orthodox Jew and he’s laying tefillin in the morning, and some passersby come and say, How would you let him do something so reactionary like pray in the morning? And they have a debate where they say, No, this is about people’s private life, their development of private belief.

This is really a question that they wrestle with, and it’s one that people think about now. Anarchists since the sixties and seventies aren’t nearly as hostile to religion—certainly not Jewish anarchists. But it’s still a question that comes up a lot, and that was really astute there. Those were two things that stuck with me throughout.

KZ: To build briefly on Anna’s mention of the “labor of organizing,” one of my big takeaways is Cohen’s emphasis on institution-building—and not just what institutions can do, but he gets into the nitty-gritty of how to keep an anarchist newspaper financially solvent. How do you run an anarchist library or an anarchist school or an anarchist summer camp or an anarchist cooperative bakery? He’s very frank about what he sees as lots of mistakes people made in various of these endeavors—precisely because he is so interested in how we create institutions that are durable and sustainable, in order to try to nudge us towards the goals that we have. That’s a particularly strong element that comes through in my reading.

SB: I could bring in some of the debates I’m hearing. As I’m reading the book—and this is very much me in 2024-25 projecting the questions we have back on—it’s hard to ignore how they deal with questions of Zionism, which was obviously an emergent movement then; the book was published before the state of Israel was founded. I was looking to see how political debates might play out, how these might be clashing—and it’s actually not that much, because it’s almost as if Zionism doesn’t have that much of a presence in the political world they’re talking about.

Maybe this is a question for both of you. How would Jewish anarchists in this period (it’s a wide period that Cohen covers) have navigated these questions about Zionism or debates around the politics of Palestine?

KZ: You’re right—Zionism only comes up at the end of the book, for Cohen. He’s writing in a very particular moment, 1944-45, where the state of Israel is just coalescing—although the Zionist movement had been growing since the First World War. Cohen is very overt in his opposition to Zionism. Talking about the Zionists in the second-to-last chapter, he says, They forget all the lessons of history that have been written with rivers of blood over the last two thousand years—which perhaps has some contemporary resonance.

Zionism was definitely debated in the pages of papers like the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, and before World War Two, it was for the most part roundly dismissed. What happens after is much, much more complicated. You can see that in some of the biographical footnotes that I have: a surprising number of anarchist individuals active in the movement who Cohen mentions, later in life, usually after World War Two, become involved in labor Zionist organization. Sometimes they remain anarchist but are supportive of socialist Zionism, and other times they abandon anarchism altogether.

It’s this historical paradox that’s created by the Holocaust and by the Jewish refugee crisis that follows, and then the reality that there are suddenly millions of displaced Jewish people living in this newly constructed state of Israel (in what had been Palestine), and trying to grapple with that and viewing it in many cases (though certainly not all cases), in the postwar period after Cohen is writing, as a necessary short-term stopgap to preserve the Jewish people—but trying to push it in the most socialist, radical avenue possible.

Then there are others—including Cohen: after he publishes this book, he moves to Paris and edits a new Yiddish anarchist newspaper, where he he’s very consistently anti-Zionist, opposed to the existence and the actions of the state of Israel, very critical of it; he visits Tel Aviv and founds an anarchist library there, and donates two hundred of his own books to it. But it is definitely striking how many others try to make some sort of reconciliation in that post-World War Two moment. That’s something that needs to be much more studied and examined from our own contemporary period.

AET: A couple things to add, for people who are interested in doing more reading on the subject: Hayyim Rothman’s work looks at resonances between Hasidic and religious Jewish thought and how different articulations of the nation are articulated.

Another article you might be interested in is Eyshe Beirich, who is a graduate student at Columbia, recently published some translations from Fraye Arbeter Shtime in Jewish Currents: anarchist responses to the Hebron massacre in 1929. That will also give you a snapshot of ways Zionism and anti-Zionism are being discussed in the Yiddish anarchist press.

We can think also of how Jewish anarchists were responding to the Churban, to the Nazi genocide. This book was published before, but there were some who interpreted the horrors of World War Two as a warning about nationalism itself.

There is an archive in Toronto from Leon Malmed’s Yiddish anarchist circle there who were trying to form mutual aid groups to support survivors and deportees after the war and were also sensitive to the issues of working class non-Jewish Poles (and other people who are working class) not recognizing a huge line between Jewish and non-Jewish war victims.

If we also think about granular attempts to organize, we can look to the Landsmanshaftn or to support for deportees and survivors after World War Two, and think about the material response to the war, not just the philosophical questions about the meaning of statehood, but how they were trying to support one another, those who were affected by the Nazi genocide.

KZ: I’m going to ask you all another question about the book. What part of the book, or events narrated in the book, most surprised you as readers, and why?

SB: There’s quite a bit that surprised me. One of the things that surprised me was the way Jewish identity becomes new, or newly discovered or newly crafted, throughout the pages of it. We’re talking about a Jewish identity that rejects nationalism broadly on the one hand, and also rejects Judaism as a binding feature of the Jewish people, and then also seeks to find what we have in common, what this relationship is that we have together, and they chart that.

Part of it is Yiddish, and digging into Yiddish as a way of fomenting a cultural Renaissance and identifying, but then hashing that out also—remembering that a large portion of their organizing in Jewish labor movement is against Jewish landlords or Jewish bosses. So there’s also this bifurcation there.

What I think is interesting here, when you put it into the context of larger Jewish history, is what point of Jewish modernity are we talking about? When we look back, that’s not entirely lost, but that is a thing of the past—Jewish identity expresses itself or is defined a lot differently, to a degree because Yiddish is no longer a large literary language, but there are probably other elements: Zionism on the one hand, the return to religious consciousness on the other. But it does feel like a period in time when all these things are possible: what it means to be Jewish opens up.

Because of that, it asks a lot of other questions about identity. What does it mean to be a part of a group? Do you choose to be a part of that group, or does it choose you? There are a lot of subtexts in all of this, there are a lot of questions about what it means to have a family life, what it means to be an insular community, how blurred the lines can be between different ethnic communities. I thought that was really fascinating throughout.

KZ: I think you’re spot on, and pinpointing Yiddish as a contributing factor—the word “Yiddish” itself, in the Yiddish language, refers both to Yiddish as a language as culture but it also means “Jewish,” at the same time. It’s the same thing, linguistically. I’ve seen some people comment that the book should have been called the Yiddish Anarchist Movement and not the Jewish Anarchist Movement, but I think that’s misguided, because Cohen and the people he talks about were very much Jewish and called themselves Jewish and thought of themselves as Jewish—but not as a religious identity, as an ethnic and cultural one.

To answer my own question—when I first read this twenty-some years ago, and then in the process of going through it with a fine-toothed comb for this edition, in some ways the most surprising parts of it are how Cohen lays out how central anarchists and anarchism were to the Jewish labor movement in the US, as well as England. And in some cases, in what might seem strange ways: the president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union for most of the 1920s was a Jewish anarchist—how you can be an anarchist and a union president is an interesting question.

Also the centrality of anarchists and of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime to Yiddish-language culture in general. It’s really amazing, both in Cohen’s telling and then going through the biographical footnotes: if you look at Jewish writers, intellectuals, and leftists at the time, they are all writing for each other’s publications. The Fraye Arbeter Shtime is an anarchist newspaper; it has a very straight anarchist editorial line—but it’s featuring socialists and Marxists and labor Zionists and territorialists, all the time, as regular contributors. And anarchists are writing for the Yiddish daily Forward, and for Di Tsukunft, and all these other Marxist journals as well.

As Shane mentioned, a lot of the anarchist component of this has been carved out of retellings of this history, particularly in English. Part of that is a feedback loop of the received wisdom that the anarchists weren’t important and didn’t matter, and therefore historians today and over the past several decades, when looking at this history, have not looked for anarchists and haven’t recognized them when they’ve seen them, quite often.

AET: I have a question which builds on that a bit. I’d be interested to hear what the book tells us about the relation between the Jewish and the non-Jewish anarchist movements. For example, there’s a passage about Margaret Sanger and some of the responses between Jewish anarchists. What does it tell us about the relation between the Jewish anarchist part of the broader anarchist movement and the Jewish anarchist contributions to the labor movement overall?

KZ: It’s a great question; while it is ostensibly about the Jewish anarchist movement in America, it discusses plenty of non-Jews in there—like Voltairine de Cleyre, who features prominently in the pages because she was a personal friend and a big part, she was a non-Jew who was very much involved in the Jewish anarchist movement in Philadelphia, and even joined the Workmen’s Circle (or the Workers’ Circle as it’s now called, and they had to make a special exemption because she was over the age limit).

Most people don’t know that any non-Jews joined or could join the Workers’ Circle, for example. A lot of these institutions weren’t exclusively Jewish, but were in fact inter-ethnic and multi-ethnic undertakings, including the Radical Library in Philadelphia; the Ferrer Modern School was a whole cosmopolitan collaboration involving all sorts of people, some of whom later became quite well-known in other capacities. The Stelton Colony—virtually all of these, other than the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, were very inter-ethnic. And even the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, as Anna mentioned, featured all kinds of translations and contributions, even specifically non-Jews writing for the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, in some cases people who couldn’t write in Yiddish, so the paper itself had to translate it.

Even while Jewishness and Yiddish were very central to the movement and to people like Cohen, they were all the time also collaborating outside of ethnic and linguistic bounds as well.

SB: I had a question that builds on that a little bit. As I was reading this, I was thinking about your first book, Immigrants Against the State, and about the relationship between Jewish anarchists and Italian anarchists, and the way that often played out in strategic debates. On the one hand, Jewish anarchists were typified (not exclusively) as having more of an organizational focus—workplace organizing and syndicalism—and Italian anarchists (not exclusively) had more of an insurrectionary background, so were talking about issues like direct action and propaganda of the deed.

A lot of those debates happened in early twentieth-century anarchism. Maybe we could talk a little about how those debates played out—either in the pages of the Jewish anarchist press or with Jewish anarchists and Italian anarchists. What was the position that Jewish anarchists usually came to on those questions?

KZ: You’re correct that speaking in general terms, the Yiddish-speaking anarchist movement was much more “organizationalist,” much more comfortable with forming official organizations that had officers and voting and minutes and whatnot, whereas the Italian-speaking movement (both in the US and Italy) was much more divided on this question, with many saying that any durable organization was prone to hierarchy and therefore should be avoided as un-anarchistic.

Cohen is himself an organizer extraordinaire within the movement, so his views on that question are pretty straightforward—although he does very clearly identify himself within the history of both the Russian and the Jewish anarchist movements as belonging to this “in-between generation,” where he talks about how the “founding generation” of Jewish anarchists were much more taken with the Russian revolutionary model, and with propaganda by the deed, and with insurrectionary violence, very much romanticized it (Alexander Berkman was the pinnacle of that in the US), and then later generations of Jewish anarchists rejected that in favor of a long-term, patient, evolutionary approach to anarchism.

Cohen identifies himself and his generation as somewhere in between, and Cohen himself—you can see throughout the pages—adored Alexander Berkman. He also celebrated every act of revolutionary violence against the tsar and tsarism in Russia. He’s by no means a pacifist or rejects violence. But he is much more critical particularly of something like propaganda by the deed or assassination or bombings, as a tactic on its own. It’s not a blanket condemnation, but it’s much more of a critical self-reflective Okay, is this actually moving things forward? How is this actually helping our movement and our cause? Which is a different question than Is this ethically justifiable?

Cohen’s story and the story of this movement is definitely in general a large contrast to the story of, say, Luigi Galleani and the insurrectionary Italian anarchists—but it’s not a one hundred percent clear dichotomy.

AET: We could certainly historicize a difference between Russian and Polish Jewish anarchist thinking on assassination, for example, and that in the US. Ayelet Brinn wrote a chapter about the Yiddish anarchists’ responses to the McKinley assassination, which is in the book that Kenyon and I edited together, but you could look to the Black Banner or other movements in Europe that are saying very different things than that in the US.

I thought maybe I would read a little bit from the Anarchist Communist Manifesto—which was published in 1921 and it’s an appendix in the book—which speaks to this question:

We are revolutionists but not terrorists. We are working to bring about the social revolution, the complete overturn of the social order. However, we oppose any attempt to interpret our teachings as an incitement to violence and expropriation. Anarchism is a social doctrine based on freedom and full equality. Violence against tyrants has its historical justification, but it is not the result of anarchism.

[…]

We are against any tendency to turn anarchism into a conspiratorial underground movement, which provides a breeding ground for all sorts of creatures who commonly infect revolutionary ranks. Only when all means of public activity have been exhausted should conspiratorial methods be used.

That’s just to give you a bit of the dialogue, there.

KZ: Precisely. Which is how someone like Cohen or the Fraye Arbeter Shtime can on the same page celebrate revolutionary action in Russia, where all other means were exhausted, but condemn something like the assassination of McKinley in the United States as being counterproductive.

AET: Yeah, and I think we see in Jewish anarchist writing in the US—there is a certain optimism about the potential for an anarchist society or an anarchist life in the US. We see it for example in responses to the Haymarket affair, or Goldman and Berkman’s responses to deportation, where they are claiming a language of free speech; they are claiming the American forefathers as their own forefathers—and it does express a certain “cruel optimism,” to use Lauren Berlant’s phrase, but a certain investment in ideals of democracy that they saw as maybe more feasible here than in Russia.

KZ: Yeah, and that dates back to even before many of them were anarchists. A lot of the early generation arrived as part of the Am Olam movement, which was a movement of radicalized secular Jewish colonization projects to try to create socialistic agricultural colonies in the US for Jews to escape the tyranny of tsarism and antisemitism and put into practice their socialist beliefs. And virtually all of those colonies failed, and many of the participants went on to become further radicalized, became anarchists.

But yeah, that urge to attempt to put anarchism into practice as a daily life and living situation is behind a lot of these things like the Stelton Colony and the Sunrise Co-operative Farm. And those types of efforts were possible to attempt, at least, in the US in ways that they would not have been possible in tsarist Russia, for example.

AET: Kenyon, could you say something about the development of Cohen’s thinking? Was there ever a moment in which he experienced radicalization? Who were his main interlocutors? You mentioned Voltairine de Cleyre—but if we think about his thought as part of an ecosystem of the anarchist world, how do you see it developing?

KZ: You see it developing in his biography from a pretty early age. He’s a child prodigy who has to lie about his age to get into a yeshiva, and then he has this crisis of faith—he becomes an unbeliever and literally has a physical breakdown as a result of this. That’s definitely a key moment in his own intellectual biography.

And then in the United States—it’s interesting: his influences and role models are not who we might expect, as a Jewish-American anarchist. He greatly admired Alexander Berkman, for example; he had many critiques of Emma Goldman’s approach to anarchist agitation (although he admired her in other ways); he had a very contentious relationship with the founding editor of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, Saul Yanovsky, which comes through crystal-clear in the book. They butted heads on all sorts of things, although later in life he grew to appreciate Yanovsky a little bit more. He also butted heads with Rudolph Rocker quite a bit, and he narrates all that very frankly. He’s not one to hold his tongue or to keep his opinion of others to himself.

At least in his own telling, a lot of the evolution of his thought when it comes to anarchism, and particularly anarchist practice—it’s less about reading a particular theorist or something, and it’s more about trial and error and the numerous projects and institutions and experiments he was involved in. He was a very cerebral, analytical guy, and he would pick apart, Alright, this is what went wrong, this is what is working, this is what is not. I think he evolves from that.

For example, later in his life when he’s writing this book after World War Two, he’s re-evaluating his own stance on the First World War, and suggests that he and others who were completely, resolutely opposed to supporting the allies in World War One may have been, in retrospect, a little bit misguided. The reason for that is World War Two, and the reckoning that World War Two brought particularly for Jews of any variety: it seemed insanity to oppose the allied powers in World War Two and therefore in retrospect what does that say about the approach to World War One? Although of course they are different complicated historical events. But that is the main cause of that self-reflection that he has.

I think it is events and experiences more than intellectual influences, if that makes sense.

L: Hey friends, butting in here because we’re getting into the final twenty minutes or so of our event. I feel like we could keep talking so much longer than we’re going to be able to.

Anna and Shane, if you had any other burning questions, I definitely want to give you space to get them in, but we do also have some great Q&A prompts that we could take a look at. We have more than we’re going to get to, but I’ll do my best to group things that are similar, to make sure we talk about as much as possible.

The thing that has come up the most are questions about settler-colonialism and indigeneity. I’m just going to read one person’s prompt, although there were quite a few getting at this. You have already kind of addressed this, but I wanted to give it a little more space since it seems to be a topic of such great interest.

How did the movement engage indigeneity? I mean that in several directions: as far as the land experiment in Michigan or Philly, recognizing they were on colonized Indigenous land here, and in terms of recognizing Palestinians as Indigenous people in the land that was colonized as Israel. I’ve been studying the strong prewar anti-Zionist work of the Bund in Poland, Ukraine, and former Pale of Settlement regions for a novel. I recognize that post-World War Two there was a shift, but thought maybe more of that direction continued here.

Could y’all share any additional thoughts on this question of settler-colonialism and indigeneity? Whether it shows up? How it shows up?

KZ: Absolutely. In Cohen’s chronicle, it does not come up, essentially. Cohen’s book is a product in part of when it was written and who it was written by—there’s no analysis of colonialism, imperialism; almost no reference to Indigenous peoples of the Americas. He does discuss Palestinians—and again, he’s stridently anti-Zionist and in that sense supportive of Palestinians’ right to live in the territory that becomes Israel.

In the broader scheme of things, looking at the Fraye Arbeter Shtime you do get some more discourse about Indigenous Americans. It tends to be much more They existed in the past but not necessarily in the present, but they do tend to be written about admiringly. There’s an interesting thing that happens during the Mexican revolution, where the Fraye Arbeter Shtime supports and paints a glowing picture of Zapata and describes him incorrectly as an “Indian chief.”

So settler-colonialism as a term and a concept didn’t exist in 1945—imperialism did, but Cohen doesn’t talk about imperialism. Even when he’s critiquing Zionism he’s not conceptualizing it in those terms.

AET: I can speak to this question. I also discuss this in my book Horizons Blossom, Borders Vanish, in a section related to how anarchists were responding to the universal suffrage movement or the women’s suffrage movement. As folks may be familiar with, a major influence on the suffrage movement by settler women, particularly in the northeast, was inspiration from Haudenosaunee societies, Native structures of society. This was a major influence for arguments that women could be political actors, had political subjectivity.

How anarchist women were responding to the suffrage movement, which had strong influence from Native thinkers and Native societies, varied. Some, like Emma Goldman, were against (of course) the expansion of universal voting. Others, like Katherina Yevzerov Merison, who I have a chapter on, were both anarchists and suffragists, and they were inspired by the suffrage movements in Europe and in the UK as well as by the construction of a feminist genealogy in which Indigenous societies, histories, and organization of life was a major inspiration.

Ways in which Indigenous history get taken up is often through a feminist lens, looking at Indigenous societies, women’s political roles and power. Are there aspects of what we might call a settler temporality (to use Mark Rifkin’s phrase) in which Indigenous life is transplanted or deferred into the past? That is one aspect. But there is another aspect in which there’s a very strong political influence looking towards Native society for an articulation of other ways to live.

That is not the same thing as coalition-building, or building relationships within a movement between Jewish immigrant, settler, and Indigenous people all together. We don’t see that. We see a lot of anarcho-syndicalist movements between immigrants, settlers to the US, versus trying to build Indigenous-immigrant-settler coalitions. But intellectually, in terms of the historiography, I see much more influence in terms of anarchist feminist thinking in turning towards Indigenous histories than I do in the writing of people like Cohen or like Yosef Luden, or several other histories of anarchism that are written by men—for whom the main issue is trying to establish a lineage for anarchism. For women, they’re trying to establish a lineage of women as having political power, and for that purpose engaging with Indigenous history is really important.

Similarly, we see moments when the term imperialism is used, but not settler-colonialism as a set phrase in that period. That said, trying to tease apart different aspects of it, there’s also a strong resonance between the decolonial moves towards valuing what we might call a “minor language,” which does resonate with Yiddish anarchist approaches—as opposed to the idea of having a universal language like Esperanto or English. There is pushback on a vision of homogenizing anarchism from within Jewish movements, and there we can see a resonance between Yiddish and Indigenous thinking on sovereignty.

I’ve tried to pull apart a few different aspects there. One might be thinking about feminist engagement with Indigenous history; another might be thinking about what some of the other resonances are between decolonial thought and Yiddish anarchist thought around sovereignty. And lastly I would point you to the work of Theresa Warburton, who also writes on settler feminism and Indigenous thought.

L: Thank you both. Those were great answers and good things to follow up on.

I’m going to throw one in from the Q&A that is a different kind of question. We’ve got somebody asking about the state of the Jewish anarchist movement today. To what extent is there something we would call a Jewish anarchist movement? How large is it? What are its concerns?

Shane, I’m imagining you might start us off on this one, but it’s a great question given the subject matter of the book.

SB: I can jump into this. This is what my next book is about. There is a large and growing self-identified Jewish anarchist movement, and a lot of it comes around the reclamation of Jewish identity—coming back and bringing it back into anarchism. But it looks very different. One of the big ways is that a lot of the ways people engage in Jewish identity is through ritual practice, reading of texts, Jewish spirituality—and that comes in a whole range of forms, from being more traditional to being totally new and innovative, but it doesn’t have that tension we were talking about earlier where there’s a certain aggressive atheism that’s built into the politics.

That’s in large part because people’s opinions about spirituality, identity, dissimilation, decolonialism—that has just changed over the last thirty, forty, fifty years. So there is a large, growing presence of that. There is also a large growth of Jewish Palestine solidarity organizing, and that’s a big component; that’s where a lot of people are funneling into that, at least in the last couple of years.

But there’s also a question that comes up a lot of how much of the modern left does have Jewish anarchism, or the Jewish labor movement, as its ancestor in general. If you look at the constituencies of modern leftist movements, labor organizing, radical projects, you’re still going to have Jews disproportionately present because it’s part of that long ancestral history, and part of that struggle. It’s one that’s continued to reinvent itself over time, but that gets to what Cohen writes about: there is a self-definition. What are we going to be as Jewish leftists, Jewish anarchists, here? That’s happening again now.

I’d be curious what both of you think about this.

KZ: I can’t claim to have my finger on the pulse of contemporary Jewish anarchism here in Dallas, Texas, and within the academy. But yes, there’s definitely a resurgence of anarchists now identifying themselves as Jewish anarchists, or Jewish leftists now identifying themselves as Jewish anarchists. Part of that is also a response to rising antisemitism and events like the Tree of Life synagogue shooting. It’s part of that, and maybe it’s part of a rediscovery of things like Yiddish and the Yiddish anarchist past.

I hope that bringing Cohen’s book to that, this history that has been so largely neglected and unknown might make a contribution to that as well.

L: I will offer the data point that this event is within our top five for registrations in the last five years. I think that says something about interest in Jewish anarchism.

AET: I think one of the other interesting developments in contemporary Jewish anarchism is an elasticity around ritual. For example, there were Shabbos events at Stop Cop City in the forest in Atlanta. There’s a thinking about what ritual can do, what a ritual space can create—or seeing ritual as a form of creativity. I think that also has a lot of resonance with contemporary queer culture, where there is an interest in ritual or embodied practice in some way.

To historicize that, we can also look at events—not just the Yom Kippur balls (which are maybe the most famous) but the use of Jewish ritual events or structures re-filled with anti-religious or anarchist content. There’s a very long line of doing things with ritual, but sometimes they’re anti-religious, and sometimes in the contemporary moment it’s more about embracing ritual as a kind of transformative moment: thinking about Shabbos, for example, as being anti-work, and how we can build on that—doing an anti-capitalist reading of Shabbat. The people who are able to do that are largely people who did not grow up inside of an orthodox community, so there is a kind of elasticity or openness to reinvention that we see in the contemporary movement.

If we think of pamphlets that were written as parodies of Yom Kippur prayers—in order to write a parody of Yom Kippur prayer, you need to know the Yom Kippur prayers really well. But there is interest in ritual as something that can be transformative, and which an anarchist lens might find generative as part of a contemporary movement.

L: We’ve got a few people asking about things that may or may not come up in the text. We know that queerness was very present in this anarchist period; certainly Emma Goldman is often cited as a queer ancestor. To what extent do some of these identities show up in the text? Do we have any discussion of queerness—and for that matter, also disability—in Cohen’s text?

KZ: Queerness Cohen doesn’t mention explicitly anywhere in the text. In some of the footnotes, I do identify there are individuals he mentions who we know were queer: people like Henry Alsberg, who was an assimilated American Jewish anarchist who met Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman in Russia after they’d been deported, and later he’s the head of the Federal Writers Project under the WPA during the New Deal. He’s a fascinating guy; there’s a full-length biography of him now.

So in the footnotes, where applicable, I have flagged that, but Cohen doesn’t mention it. There’s one case where I’m very tempted to think that there is a queer back story—but this also links to disability. There is a blind member of the Fraye Arbeter Shtime collective named Aaron Mintz, who was blinded from tobacco poisoning, from rolling tobacco as a cigar maker. He lost his eyesight, and lived with a close friend named Nathan Weinrich, who was his “eyes.” They were inseperable. Mintz, even though he was blinded, still remained an important literary critic. His helper/partner would read to him, and he had a great mind for these things, and he would remember all of the texts and the literature that was read to him.

I’m so tempted to attribute some sort of queer relationship to these two. They did live together, and if you look them up in the census, there is one census where they even listed as partners. There is no smoking gun, but it is easy to imagine that there’s a story there.

In terms of disability beyond that, there’s not a lot that’s mentioned. Cohen doesn’t even mention the fact that he himself had had to quit his job as a cigar roller because he developed asthma, or the fact that his wife Sophie ended up with a debilitating disease. In his telling, it’s not central, certainly.

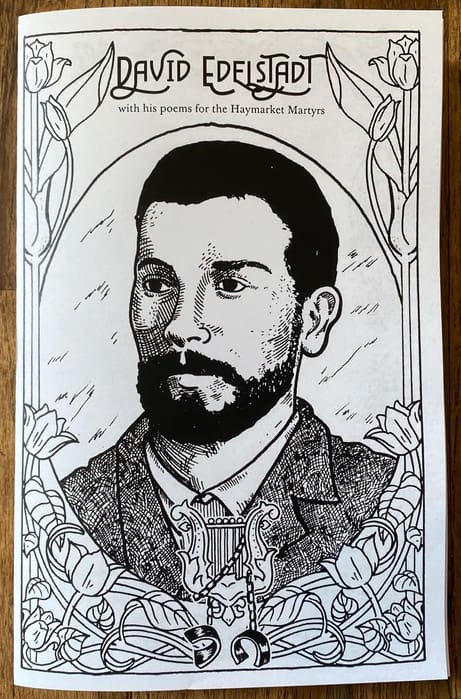

AET: We can think about mutual aid and care practices as certainly being very central for anarchist thought and how people were trying to organize their communities (that doesn’t mean that men were making the coffee, though). But we can think about David Edelstadt, who was a Yiddish poet who had tuberculosis, and at the end of his life he was in a sanitarium in Colorado.

How is illness or disability written about in terms of Edelstadt? He was seen as a saintly figure who was self-sacrificing. He refused to accept money for editing Fraye Arbeter Shtime, for example. So we can certainly think about a discourse of care and how disability was viewed in that period. We can think also about Voltairine de Cleyre’s response to being shot. She was assaulted by a man who was considered mentally ill, and she chose not to press charges or pursue that case. There was a lot of interest in how she responded, the care she was extending to this person who was considered to be mentally disabled, and how he is represented and how her act of care was represented. There was a lot of interest around that.

To the question about queerness, certainly with Goldman there were love letters between her and another woman, and with Margaret Anderson, who was the editor of the Little Review—she was publishing James Joyce in Chicago and writing these incredibly florid letters to Goldman.

But we can also think about whether there is an inherent queerness in a movement for comradeship. Is there a queer desire or a queer longing to reorganize society not along the lines of biological family? Is there a queer discourse of comradeship in and of itself?

L: An incredible question which we could definitely have a whole evening on, and I would love to. We are unfortunately reaching the end of our ninety minutes. I do want to make a little bit of space before we sign off tonight just to hear about any projects that y’all are currently working on or any places that people can go to connect with you or your work after this event.

KZ: I’m currently working on a big book project that’s a global history of the deportees of America’s first Red Scare, tracing folks beyond Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman who were deported between 1917 and 1925, and what they did and the effects they had on the wider world. You can see some work in progress on that at a website I put together, and I have little biographical profiles of 735 deportees up there at this point.

AET: You should read everything that Kenyon’s written and that Shane’s written; if you’re in Chicago, I’m teaching a class called Stateless Imaginations, which is on world anarchist literature. I also wrote a book called Horizons Blossom, Borders Vanish, which is on anarchist literature in Yiddish: elegy and radical forms, modernism, avant-garde anarchism that runs through a hundred fifty years of Yiddish literature.

SB: Thanks for having me here. I’m just now finishing a book on mass movements and antifascist organizing, and starting one on the future of the Jewish left. That’ll probably take me a couple of years, so I’ll be writing a lot on both of those subjects for the next year or two as I’m working.

KZ: Let me just plug: if any of you are considering purchasing any of these books, consider doing it through Firestorm and supporting a great project.

L: Thank you for that.

It’s been a sincere pleasure. My deep and sincere apologies to all of the people who submitted Q&A topics that we didn’t get to. There was so much good there.

This was such a delightfully nerdy conversation, and I hope we’re able to have more like this in the coming months. On that note we have to call it. I hope y’all have a great evening. Thanks, everybody who joined.