Mutual Aid in the 1919 Seattle General Strike

a zine by Jennings Mergenthal

24 July 2025 (read | print)

The Context

In 1919, Seattle was a very different place. It had been officially incorporated for only fifty years. Pre-colonization was still in living memory for the seventeen Duwamish villages displaced by the settlement. Seattle has grown rapidly into a population of 310,000, a bit smaller than Minneapolis.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Great War (the last war that will ever happen) has just ended a few months ago. The recent Russian Revolution is serving as a source of hope and inspiration for leftists internationally, including in America.

Unionization is on the rise, but faces harsh resistance. A few years before, union supporters were violently attacked and killed in nearby Everett. During the War, the government mediated a truce between labor and management to prevent strikes or lockouts from disrupting the war effort, but this fragile managed peace has fallen apart following Armistice.

The city has also just emerged from two waves of the devastating influenza pandemic. Globally a third of the world’s population was sickened, and between 50 and 100 million died as a result of the disease. In Seattle, more than

1,400 died and the city repeatedly shut down and employed a mask mandate.

Elevator operator with an influenza mask. Seattle, 1918.

Museum of History and Industry

The War also caused massive economic inflation due to shortages, but wages have not kept pace. Housing shortages similarly meant that the cost of living in Seattle is exorbitant. Working conditions, particularly in industrial fields, were unregulated and dangerous and many of Seattle’s unions are full of disgruntled leftists.

Seattle Union Record, November 1, 1913

So perhaps Seattle was not quite so different then as now.

About Strikes

A strike is a work stoppage. A union goes on strike generally because of a disagreement with their employer, and in the process, they forfeit their pay.

“Solidarity,” by I. Swenson, Seattle Union Record, February 11, 1911

In a sympathy strike, another union stops its own work in support of strikers, even though the strike is not with their own employer.

When a strike spreads to a large enough proportion of an area, it becomes a general strike. General strikes are powerful and difficult to organize. They are usually governed by a strike committee, elected representatives from unions who can vote on decisions and actions on behalf of all striking workers, including when to end the strike.

General strikes are also controversial. The Seattle strike was opposed by the more conservative national federation of unions the American Federation of Labor. But still, successful general strikes inspired by this one were organized in Winnipeg in 1919 and in San Francisco and Minneapolis in 1934.

Sympathy strikes (and therefore also general strikes) have been illegal for the vast majority of unions in the United States since the passage of the 1949 Taft-Hartley Act.

The Strike

Following the end of the War, shipyard workers in Seattle began to negotiate higher wages. Negotiations broke down after shipyard owners offered only raises for some workers. On January 21, 1919, the 35,000 shipyard workers went on strike. The majority of those workers were employed at the Skinner and Eddy Corporation.

Workers engaged the Seattle Central Labor Council, who polled support for sympathy strikes. Receiving near unanimous support from 110 local unions, a general strike was set for February 6, 1919 at 10 am.

At this time many unions were racially segregated, but the strike was even supported by Japanese American unions, who were not permitted to vote in the strike decision.

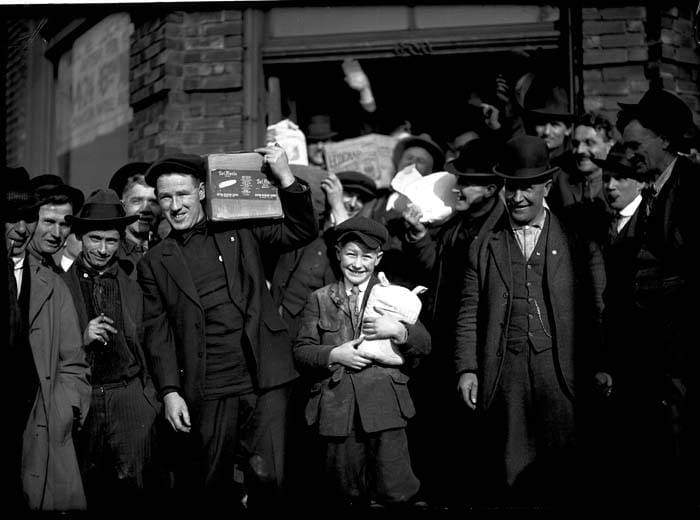

Workers leaving the shipyard, University of Washington Special Collections.

Corporate owned newspapers tried to fearmonger about the impending strike and encourage dissent.

Tuesday February 4, 1919, two days before the strike.

While theirs were prominent among the local newspapers, the labor-owned Seattle Union Record took a strong pro-strike stance.

Also Tuesday February 4, 1919, two days before the strike.

On Thursday at 10 am, 65,000 Seattle workers walked off the job. Despite the apprehensions of the corporate class the city did not plunge into chaos, mobs did not fill the streets.

In fact, strike organizers encouraged people to stay home. In this editorial, titled “No One Knows Where,” Anna Louise Strong made three pledges to mutual aid that we will evaluate over the coming pages:

Labor Will Feed the People

“Twelve great kitchens have been offered and from them food will be distributed by the provisions trades at a low cost to all.”

This was actually an understatement, there would be twenty-one kitchens offered by restaurants across the city. The food was donated or purchased by the unions, prepared in the kitchens, and transported to dining halls where it was served cafeteria style.

On the first day, there were logistical delays such that the first meal was not offered until nearly five pm and there was a shortage of dishes. By the next day, this had been resolved and disposable dishes (paper plates and pasteboard cups) were provided.

Striking workers were fed for 25¢ per meal ($4.50 today) and members of the public could eat for 35¢ ($6.40), but reportedly none were turned away for lack of funds. The halls fed more than 30,000 meals a day with service organized by volunteers belonging to the the Waitresses and Waiters union Local 240.

Drake and Ray restaurant, used as one of the kitchens. Bettman Archive.

Alice Lord (center), the president of Local 240, and other local members serve meals at one of the dining halls. Museum of History and Industry.

Labor Will Care for the Babies and the Sick

“The milk-wagon drivers and the laundry drivers are arranging plans for supplying milk to babies, invalids, and hospitals, and taking care of the cleaning of linen for hospitals.”

The milk-wagon drivers’ union established 35 stations across the city for milk distribution. The milk was purchased by the union from farmers and each dairy station was open from 9am to 2pm. Similar to the dining halls, there were no reports of those without funds being turned away.

The Seattle Mutual Laundry Company, established in 1915, was a worker-owned cooperative. They were exempted from the walkout in order to continue to provide laundry service to hospitals to maintain sanitary conditions. The laundry was collected in wagons labeled “Hospital Laundry Only, By Order of the General Strike Committee.”

Drug stores remained closed, except for prescriptions services. Garbage collection also continued with restrictions under the advisement that they “may carry such garbage as tends to create an epidemic, but no ashes or papers.”

Ole Lowell and son Herbie c. 1916 (not part of the strike, but a comparable era)

Wedgewood in Seattle History

Mutual Laundry Company Building

University of Washington Libraries

Garbage collection in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, circa. 1915

(Similarly not part of the strike itself)

Seattle Mutual Archives

Labor Will Preserve Order

“The strike committee is arranging for guards and it is expected that the stopping of the [street]cars will keep people at home.”

The Stike Committee organized the Labor War Veteran Guard. Guards were unarmed and wore white armbands, serving eight-hour shifts both day and night. One guard member described his intentions:

“Instead of a police force with clubs, we need a department of public safety whose officers will understand human nature and use brains and not brawn in keeping order. The people want to obey the law if you explain it to them reasonably.”

During the strike, arrests fell from more than a hundred per day to less than thirty, with no strike related arrests.

The guard members were unpaid, and were passing up the $6 per day that they would have received if they had joined the 2,400 armed citizens deputized by the mayor as an auxiliary police force.

Armed citizen brigade. Evening Herald, 1919. Wikimedia Commons.

Strike bulletin published daily with information about the strike, this one from day two. University of Washington Libraries.

Evaluation and Analysis

By Sunday (day 4 of the strike), Mayor Ole Hanson threatened to impose martial law. Some unions, including the more conservative element of the Street Car Men’s Union returned to work.

By Monday morning, even more workers had begun to return. The Strike Committee called an official end to the general strike effective Tuesday at noon. The shipyard workers remained on strike for another month, but failed to win significant concessions. The strike became national news because of the disruption to business. A number of the organizers were prosecuted for sedition, becoming part of the first Red Scare, leading to increased persecution of leftists and immigrants nationally (and in Seattle specifically), though the sedition charges failed to stick. In Seattle, employer policies turned sharply against unions and the Seattle Central Labor Council spent the next generation under reactionary conservative leadership.

Conservative contemporaries of the strike regarded it as a failure because it did not lead to the rise of an American Bolshevik revolution. This is true, but also wasn’t the point of the strike for most striking workers.

A key part of the strike’s effectiveness was the organizational structure that allowed the facilitation of mutual aid, which kept the strike popular among impacted residents. The tangible reality of day-to-day life is just as important to most people (if not more important) than the abstract concept of solidarity and we need to figure out how to engage with both so that they may feed each other. The strike was a disruption to industry, but mutual aid met the material needs of the impacted strikers and their families.

The strike was able to effectively organize because of the groundwork of the preceding decades. The workers in Seattle belonged to active, organized local unions and a central labor council had been in existence for thirty years. People had a vocabulary for and engagement with labor and labor activism that largely does not exist now (in large part because of the past century of retrenching conservative interests and the inability of establishment liberals to present a contrasting vision).

In short, the general strike could be organized because people were already organized, which was a long, slow process of building investment in solidarity and shared identity as workers. They could strike because they trusted that their material needs would be met.

This is why, however well-intentioned, social media calls for a general strike are ineffective. In order to work, a strike needs to be accompanied by infrastructure to support the needs of the strikers. While a general strike is a good eventual goal, more important in the short term is working to build a sense of community engagement and investment such that people can come to rely on their communities and build a mutual network of support.

Sources and recommended further reading:

Cal Winslow. “When the Seattle General Strike and the 1918 Flu Collided. Jacobin. 2020.

Cal Winslow. “When Workers Stopped Seattle.” Jacobin. 2019.

Cal Winslow. Seattle General Strike: The Forgotten History of Labor’s Most Spectacular Revolt. Verso. 2019.

Coll Thrush. Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. University of Washington Press, 2017.

Robert Freidheim. The Seattle General Strike: Centennial Edition. University of Washington Press, 2018

“Seattle General Strike.” University of Washington Special Collections.

The Seattle General Strike: An Account of What Happened in Seattle and Especially in the Seattle Labor Movement, During the General Strike, Feb 6 to 11, 1919. Left Bank Books and Charlatan Stew. Seattle, 2009.

“Seattle: Washington.” The Influenza Encyclopedia.

“Strike: Seattle General Strike Project.” Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium / University of Washington. 2009.

Featured image: Museum of History and Industry.

For more information, please visit puppetstudies.org

Download PDFs to read, print, and share: