by Antidote’s Ed Sutton

for the occasion of the one year anniversary of StandortFUCKtor and the breaking of a young Swiss movement to Reclaim the Streets

Tim stood, collecting himself, on the Bahnhofplatz in Winterthur. It was late, but the plaza was swarming with people. As he looked around, trying to make sure he wasn’t in anyone’s way—the crowd streamed around him with uncommon purpose—he kept getting partially blinded by the yellow, haloed streetlights, which seemed too numerous and stood at odd angles.

Anxiety rose in his throat. He really hoped he wouldn’t vomit again—even if he was able to swallow it back like before, this time somebody would definitely see. The adrenaline of being chased was already wearing off, and he was dismayed at the disorientation it left behind. Composure, he said to himself, composure.

He found a spot to the side of a bus shelter where the currents of people, parting, created a vacuum. Leaning back against the plexiglass, he turned his face skyward, eyes closed, and breathed in deeply through his nose. The September air was unpleasantly sharp. When he opened his eyes, the blackness of the sky, insistent behind the shimmering lights of the plaza, dazzled him.

Then an unexpected blow caused his whole body to tense. Somehow resisting the impulse to recoil, or to strike back, he turned slowly to see what he was dealing with. His glance lit first on discordantly shiny shoes—then leapt, startled, up to a familiar face. But Tim’s relief mixed with the tang of being caught out. Alex was the last person he expected to see here, now.

Alex looked just as baffled as Tim was, but much more amused. He unclenched his fist and offered his hand.

Tim took it, poorly concealing his embarrassment with a weak smile. Alex had already seen the worst of Tim, many times—as Tim had of Alex as well, but for some reason it bothered Tim much more, exacerbating the feeling of grubbiness he had always had in staid Switzerland. Alex came from a rich family and worked in finance. He dressed well. Tonight was no exception.

And Tim knew he looked like soggy shit. “What are you doing here?” he asked, after an awkward pause made clear that Alex’s playful assault was supposed to count as his greeting. He focused his eyes on Alex’s face, for practice focusing his eyes, and relaxed slightly: Alex was drunk.

“Emily lives here.”

“What are you doing here?” Emily broke in. Tim hadn’t seen her there, and immediately felt bad about it. He was thankful that her greeting was rude, though; he didn’t want to have to give her the three Swiss kisses. He was pretty sure he smelled like throwup and teargas. And he didn’t like her.

“I mean all of you.” She gestured down to where the plaza inexplicably and seamlessly became a trafficked intersection. The throng of people was dammed there by a police barricade, which concealed from view the wide alley further down where demonstrators were kettled, the alley from which Tim had just escaped—rather astonishingly, it occurred to him now.

Tim looked from the barricade to Emily to Alex, and back to Emily. His mouth tasted bad. “Hard to say,” he managed, un-shouldering his backpack to search for gum for the third time.

Emily’s eyes twinkled with triumph as she directed her gaze at Alex: “I told you the people at these dance demonstrations don’t even know what they’re for.”

Tim’s body tensed again. Though less caustic than other recent public commentary around what was starting to look like an emerging Swiss Botellón movement—“Give ‘em a good whooping and put ‘em away for a while;” “Better yet, stand ‘em against the wall!”—Emily’s declaration was no more creative. Tim had heard variations of this dismissal often enough that his activist’s conceit demanded he have an air-tight comeback.

Instead he heard himself muttering something about the movement’s short- and long-term goals being misaligned, thinking this might at least convey that he was aware of the movement’s goals. Emily looked at him for several beats. Alex grinned, masking either incomprehension or discomfort, or both.

Then they were gone. The crowd was thinning, though the floodlights from the police trucks down at the kettle still glared relentlessly; it would be hours before all 93 people, trapped like rabbits, would finally get hauled off. Occasionally the crack of either a police rifle or a demonstrator’s bottle rocket—the two became indistinguishable after a while—sounded distantly.

Tim zipped up his backpack, having found no gum but instead, as consolation, a bent cigarette, and moved slowly away from what had very nearly been a very long night, toward the train platforms.

* * *

Earlier that year Tim had been traveling in France with some American friends he hadn’t seen in some time. In the course of catching up, he had told them about the previous dance-demos he’d been to. The one in Zurich which had spontaneously emerged out of a party at a squat; the one in Bern which—he heard himself bragging—was in its third year and was huge; the one in Aarau which had filled the medieval town’s streets and, ending up in a wide open field in the Aare river valley, had lasted until the wee hours.

In each case, he left out the part about the cops clamping down and the ensuing street battles. He proudly emphasized, though, that the Aarau demonstration—largely unmolested by the police—had gone smoothly, and complained that media reports the following day focused only on minor damage in the city, praising the police for having “kept the peace.”

His friends had been incredulous. “That could never happen in the U.S.,” Aaron had said. “The cops would crush that shit instantly.”

* * *

“Yep,” Tim had thought. In his telling of tall tales, he had convinced even himself that Swiss society was more open and tolerant than America with its smiling corporate fascists and their military police. In Switzerland, colorful, party-like demonstrations against rising rents and the commercial hollowing of city culture were not only possible, but common!

So when he arrived in Winterthur that night in September, he was surprised and annoyed to find a wall of police vehicles and riot cops blocking his way right in front of the train station. He smirked at himself as he realized that he’d been wound up all the way here because he was late—as if he were commuting to work! Now the police seemed, inappropriately, like one last exasperating obstacle.

He approached the line. The demonstration was just visible behind them, down the slight incline of Bahnhofplatz, and its mobile sound systems boomed. A cheer went up. Shop windows, billboards, and ticket machines all along the plaza had been secured—rather absurdly, Tim thought—with plywood.

The cops stood in loose formation; they appeared to be letting people out of the cordoned-off demonstration, but they weren’t letting anyone in. Tim made for a gap in the line, but two large cops closed rank in front of him.

He pulled out his phone, pretend-casual. “What’s going on down there?”

The cops’ faces were dimly visible behind the reflections in their visors. Neither answered for a moment. In the near distance, a barely intelligible dispersal order was being read through a megaphone.

Tim gestured between the two cops’ shoulders. “May I?”

“You don’t want to be in there.”

Tim wasn’t sure which cop had said it. So he smiled at both of them and turned, heading into the city’s old town to look for another way around.

* * *

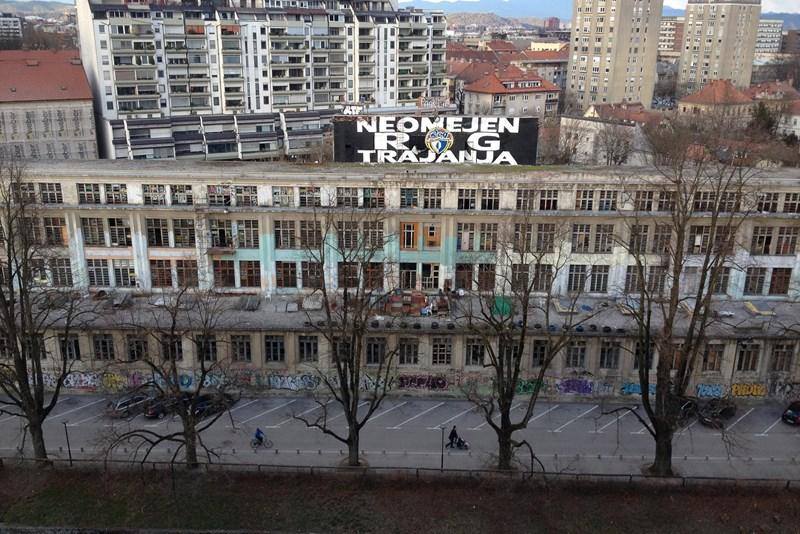

The demonstration, when he reached it, had strayed off the main road toward the mouth of an alley where the former loading-dock back doors of warehouses had been turned into the front doors of pseudo-chic nightclubs. He thought, optimistically, that there were a couple thousand people there. Most of them were dancing in front of the various sound trucks, which in the cramped space combined their divergent offerings into one glorious cacophony.

Tim gravitated towards the one with a punk band standing on it, near the far edge of the crowd. There were some crusties slam-dancing and others bobbing their heads distractedly, but several people were facing away from the stage with worried looks on their faces. Tim followed their gaze up in the direction of the train tracks a block or so away, and there saw the lights of a water cannon truck, resembling an alien spacecraft, blurred by spray as it impolitely coaxed people toward the alley where he was standing.

A lot of people started moving into and down the alley, some walking up along the connected former loading docks and finding the clubs, ominously, had closed and locked their doors. Tim moved with the crowd, trying to arrange his scarf so that he could breathe through it if he had to. He was kicking himself for coming alone, stupid, stupid, stupid. He had always had people to meet, who understood to look out for one another.

Now he began seeing people coming back the other way. Up ahead, the far end of the alley was throttled by a neat rectangle of riot cops flanked by two armored trucks. Preferring them to the water cannon on a chilly night, he continued forward.

As he neared the police line, a well-dressed young woman—‘with a little handbag and everything,’ Tim thought—began arguing with them, gesticulating broadly. They wouldn’t let her and her friend through.

A sudden jet of chemical vapor rudely moved the two back. Tim and everyone around him cringed simultaneously.

“What is your fucking problem?” screamed the woman. More spray. The air was getting heavy.

Suddenly being pushed forward, Tim looked over his shoulder and saw a couple of bottles sailing in glinting arcs in the direction of the water cannon, which had now been joined by another. Each had its entourage of masked men around it—firing rifles? Can that be?

The thought in Tim’s mind was the same as everyone else’s: “I’ve got to get out of here.”

* * *

In the weeks following, exchanging stories with friends (who, it turned out, had also been at the dance—he just hadn’t been there long enough to have found them before the cops suddenly decided to close the noose), he still couldn’t explain how he did it. He had seen others, smarter than him, slipping out before the trap had fallen to, but he had waited too long. It really didn’t make sense.

“You’re just being coy,” said Amelia. “Or are you protecting the identity of the magic person who levitated you out?”

Tim just shrugged. The truth was, he felt bad. He knew it was vain, but he felt bad that he had been so stupid and had still gotten off so easy, when others, friends, had been hosed down, gassed, shot, and caged. He read about the young woman, an art student, who had been blinded in one eye by a rubber bullet, and he felt bad. Then he read about the August Rabaa massacre in Egypt, reports of which continued to worsen a month later, and he felt bad about feeling bad.

But he felt even worse about Alex, who in a more sober moment a few weeks later asked again why Tim had been in Winterthur.

“I saw some stuff on Facebook, banners and slogans and stuff,” Alex continued without waiting for an answer. “‘Gegen Aufwertung?’ Who could be against increasing value?” He laughed, completely unselfconscious.