Transcribed from the 16 September 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Supply of most types of housing makes no difference to the housing problems faced by poorer groups, as they simply cannot afford most types of housing.

Chuck Mertz: There is a housing crisis, and the way it is usually addressed is growing the supply of “low-income housing.” What if the problem with low-income housing isn’t supply? What if the real problem is those who demand housing simply cannot afford it? What if the problem with housing is capitalism?

Here to help us understand the housing crisis, geography scholar Dr. Deborah Potts is author of Broken Cities: Inside the Global Housing Crisis. Debbie’s previous books include her 2006 work African Urban Economies: Viability, Vitality or Vitiation, and the 2010 title Circular Migration in Zimbabwe and Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. She recently retired from the geography department of King’s College London, where she lectured at the School of Oriental and African Studies. She is now an emeritus reader in human geography and a member of the urban features and contested development research domains at King’s College.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Dr. Potts.

Deborah Potts: Hi, Chuck. Thank you.

CM: How would you describe the current housing crisis that we face? What is the current housing crisis? In case there are people listening right now who are unaware, for whatever reason, that there is a housing crisis.

DP: There are two aspects to it. One of them is the immediate material issue: the lack of affordable housing for low-income groups is a chronic condition of capitalism. From the end of the last century and up until this current time—and unfortunately, I believe, also into the future—this has shifted further into an increasing crisis. The chronic condition has become increasingly critical, and it’s getting worse and worse.

That’s the material thing. There are a whole series of things behind it, the key one being that from 1980, as we all know, the system of global capitalism shifted away from the postwar social contract, which was extremely influential in Europe in mitigating the worst aspects of capitalism for the poor, in a very crude sense. Those things have been very rapidly unpicked, particularly after the financial crash of 2008.

But the other thing about the housing crisis is the concept called the housing dilemma. The housing dilemma is the idea that it is actually impossible for capitalism to address the problem of housing affordability: embedded in the nature of profit-seeking capitalist activity in property sectors are a set of conditions that make it impossible to make profit out of low-income people. You’re trying to square a circle there if you rely on them supplying housing. That is never going to work.

Right throughout the world—and it doesn’t matter whether you’re in Harare in Zimbabwe or whether you’re in Mumbai or Rio de Janeiro or Chicago or London—this repeats itself over and over again. And it’s increasing—it really is a crisis now. It’s gone beyond the chronic condition.

CM: When it comes to responding to the housing crisis, you write, “The logic is that if enough houses were built, market prices would fall into line with demand: the magic of the market, of the Invisible Hand, would provide the solution. That approach looks at the housing crisis, which is manifest across the urban world (and most particularly in the largest cities where economic opportunities are apparently greatest), from the wrong end of the telescope. The real problem is demand.”

So it’s not a shortage of supply, it’s an abundance of demand at the heart of the global housing crisis. How do we understand the housing crisis differently when we view it as too much demand and not too little supply? The interdependence of supply and demand can lead to the two being conflated and possibly difficult to separate and think of independently from one another.

How do we view the housing crisis as a problem with demand and not a problem with supply? How do we view that differently?

DP: The issue here is that housing markets are segmented. People are often familiar with the idea of labor markets being segmented, that there are situations where lots of people can be in the high end of the labor market, and increasing the numbers of people in that end of the market is never going to satisfy demands for nursing assistants or something at the other end of the market. This is the situation also with housing.

Supply of most types of housing makes no difference to the housing problems faced by poorer groups, as they simply cannot afford most types of housing. If we look at demand, we have to look at the labor market. If we look at the labor market in any society, we can find huge numbers of jobs, hundreds of millions of jobs across the globe in urban situations, where if people set aside money, they can just about afford to pay for their housing (which is always the largest element of the budget) and leave enough for them to eat and clothe themselves and send their children to school and various things like that. Most housing that is legal and decent (these are crucial points) is simply too expensive for them to afford. They just can’t afford it.

That is the problem. If we look at it from the point of view of monetary demand (and that’s what the laws of supply and demand about about), they simply do not command sufficient monetary demand to house themselves in a legal, decent way through market processes.

CM: So is the problem not a shortage of supply of housing but a shortage of supply of money for the poor? If that is the case, what would explain to you why housing advocates, people who want to help the poor, would be pushing for a larger supply of low-income housing instead of higher wages for the poor?

DP: It could be tackled from both ends. There are people who argue that the thing to do is increase everybody’s wages: have a minimum wage which is sufficiently high for people to command enough monetary demand to enter the housing market. That would work, but I have to say that I think it’s fantastically unlikely, particularly since the scope of this problem is global. I’m looking at societies in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, where people aren’t even beginning to touch the side of the possibility of earning enough money. You’d have to increase their incomes perhaps by thirty- or forty-fold. This isn’t going to happen.

We have massive amounts of supply—an oversupply—of expensive housing and middle types of housing as well, and a shrinking and reducing supply of affordable housing for those on low incomes.

You are right, however, in saying that another way of answering this will be to greatly increase the supply of housing that is suitable for low-income people. However, that housing always involves significant subsidy from the state—or let’s put this more broadly: it involves non-market solutions. It doesn’t always have to be straightforwardly from the state. Collective approaches to issues to do with property can also help. But it is a matter of state intervention to ameliorate the situation and provide housing that is significantly below the market rate. If you can provide that sort of housing at scale, you will solve the problem.

In Britain, for example, which had the largest council housing projects in the whole world in the postwar situation (we built millions of council houses), by the end of the 1970s we had actually solved the housing dilemma. There was no shortage of housing. People who were in low-income jobs could move between different parts of the country. They could gain access to long-term housing. They would not be evicted or moved. They could live their whole lives there, and their children could move into the housing as well, and stay in the housing. We had solved the problems.

However, we know what happened at the end of the 1970s. The postwar social contract started to collapse. Margaret Thatcher came to power in the 1980s and it all began to come undone. All that council housing began to be picked away at and disappear, or sold off and privatized. As it has become privatized, it has been taken out of the pool, so the pool has been shrinking and shrinking.

We have massive amounts of supply—an oversupply—of expensive housing and middle types of housing as well, and a shrinking and reducing supply of affordable housing for those on low incomes.

CM: Was it simply unaffordable? That was the argument at the time, whether it was the Thatcher government or the Reagan administration: that we may have solved the housing problem but it isn’t sustainable because the government simply can’t continue to afford it. Was that actually the case at the time? That was the biggest argument for neoliberalism.

DP: No, not at all. There is no evidence for that. It was tremendously successful. That wasn’t the problem. That was not the reason why those things were being picked away at. The reason was an ideology which obviously you are familiar with. It’s almost a knee-jerk thing, it’s so deeply and inherently held by ideologues of the neoliberal phase of capitalism: that the government should not intervene, as little as possible, and that things should be left as much as possible to the private sector.

In addition to that, the previous system didn’t make a great deal of money for big property developers. Much of this stuff was built by the state (unlike in America, for example) and run by local government—this was not creating profit for property developers and builders. America is the apex of property development’s financialization of housing worldwide, whereby the government does intervene (it would be wrong to say the government doesn’t intervene at all) in ways which always provide as much profit as possible to the capitalist housing sectors. That is quite explicit in the way that American government policy works.

Here in Europe—and also all the way across the world, from India to Africa to Latin America—those ideologies and ideas came in the 1980s. It happened before my very eyes, because I work on sub-Saharan Africa. I was watching successful low-income housing projects which were delivering site and service plots to very, very poor people, giving them a chance to live reasonably within the city limits and have access to basic services which are absolutely crucial—water, sewage, and so on—and seeing those just melting away before my eyes because there was no profit in it. They started to bring in building societies, started to bring in ways of financializing it, trying to loan money to these very poor people. To cut a very long and very sad story short, they couldn’t afford it, and the whole thing fell apart.

When we look into these housing projects, we often find that lots of these things that were promoted and publicized as “low-income” housing projects were no such thing. Because the very lowest amount of money you would need in order to be eligible to be what they call a ‘beneficiary’ of such a project was way over the incomes of the vast majority of the people who were actually living in them. In fact, nearly all of them were renting from other people who had got in through various corrupt and elicit practices. This was extremely widespread, and it goes on and on. There is constant ‘poor-washing,’ where projects are promoted as ‘low-income’ or as ‘affordable housing’ (that’s the term always used now) when they are no such thing. It is just a political distraction technique from what is really going on.

CM: We have politicians who support neoliberalism; neoliberalism is always seemingly focused on the bottom line. Is this privatized ‘low-income’ or ‘affordable’ housing any cheaper? Does it cost any less for the public’s bottom line than public housing did in the past? That’s another aspect of this. It’s supposed to save the public money, and deliver the service in a much more efficient way.

Is this kind of privatized public housing any less expensive to taxpayers than the previous public housing was?

DP: It’s a good question. It would be so variable I should be careful not to answer in the absolute. But it probably is. It probably is cheaper. The trouble is—let’s think of another sector: if we just stop funding nurses, if we cut the National Health System that we have in this country, cut it and cut it, we do end up spending less money on it. The outcome, of course, is that a lot more people die; a lot more people have very poor health. So maybe we do spend less, and particularly local governments end up spending less (because they actually weren’t allowed to spend: it was forbidden in this country for local governments to build more council housing), but on the other hand the outcome is that people don’t have access to affordable housing.

And what happens is a slow-onset disaster. It doesn’t happen just like that. It didn’t happen immediately in the 1980s. It was gradual. It started to build up, and in the 1990s it got worse and worse. We got a system where people start to become housed (and I’m talking about wealthy cities in particular, like Barcelona, London, Berlin, Rome—let alone American cities) but increasingly in inadequate housing. They are overcrowded (this has become extremely important in this current pandemic). They are dangerous. They are paying far too much of their so-called ‘disposable’ income after tax for the accommodation they’re living in. As a consequence, they suffer because they can’t eat properly. They struggle to get to work because they can’t afford transport. All sorts of necessary things that are needed for them to live full and healthy lives are being cut into, because they pay too much in rent.

The outcome is not that they have affordable housing and the cost to the state has gone down. Whether the cost to the state goes down or not, they are not living in decent housing. That is an extremely poor outcome.

During the twentieth century, the primary way urbanization happened and urban processes of housing worked their way through the world (it’s global) was through people housing themselves in irregular, informal ways.

CM: If, as you were describing neoliberal ideology, it is wrong to provide subsidies and therefore right to have a housing crisis—does that make the housing crisis easier or more difficult to address? If it’s not a function of the market but of ideology?

DP: It is a function of the market. It’s a chronic condition of capitalism that lower-income people in the income distribution of any city are not going to be able to house themselves decently and legally. That’s true if you’re in Nairobi or Lima or New York. They’re not going to be able to do that if there is a reliance on capitalism and private-sector for-profit provision. That is a chronic condition. It is a problem of capitalism.

There are different phases of capitalism. This is perhaps more apparent if one lives in Europe, because of the tremendous significance of the postwar social contract, which really did change the nature of capitalism. We still had capitalism; we still had governments that were largely working hand-in-hand with the private sector and doing what they could to help it along and so on. But the nature of the Second World War had brought about a significant moment, as it did in America, too. There were all sorts of housing policies which certainly didn’t work out evenly in terms of who they benefited, but they did benefit some people on low incomes who would not have been able to enter the property market before. In Europe there was a massive revision of subsidized housing and indeed subsidized health, and it was this that made much of Europe a pretty good place to live at that time.

But capitalism is always reinventing itself. Neoliberalism is not a new ideology of course; it goes back to the nineteenth century old-fashioned Liberalism of free trade and all the rest of it. But this next neoliberal phase that comes back to that: we want free trade, we want free markets, we want a situation where the main role of government is to facilitate entrepreneurs, profitmaking, and so on; we can provide the services that are absolutely necessary for that (an educated population, for example, in certain circumstances) but will leave to the market things such as the provision of housing.

This is the way the nature of capitalism and of government policy shifts over time. It was reshaped after the 1980s.

CM: And you say that the measurement and conceptualization of what is affordable housing is deeply political. How would you describe those politics? What would you call a politics that allow for this kind of housing crisis?

DP: It is deeply political. The late Michael Stone was the guru in America who researched and wrote about housing affordability in the States. And it happens, I have to say, all over the world. There are tremendous people working on this in sub-Saharan Africa as well. But it comes down to the setting of the standards in terms of understanding how much a family, a household, or an individual can be expected (or, in a way, allowed) to spend on their housing for it to be affordable. The thing about housing is it’s the largest part of your household budget, and it’s not something you can reduce. It’s not like food. You can live on very cheap food for a month and next month wait until your income improves. This doesn’t work with housing. If you’re renting you’re likely to get evicted. If you’ve got a mortgage, they’ll foreclose on you. These things cannot happen.

How much you’re expected to pay is absolutely crucial. Many housing advocates and agencies take a rough rule of thumb of about thirty percent of disposable income. Of course if you’re very rich you could pay seventy percent of your income on your housing and still have masses of money to live on. But if you’re middle-income, lower-income, or poor, thirty percent can be too much. And again, thirty percent is a rough rule of thumb: most people in London and New York and Chicago are paying way, way over that. When low-income people are paying over that, it is really eating into the amount of money they have to spend on other things.

It is very easy for politicians to say things like David Cameron, one of our previous prime ministers, who just said he thinks people make too much of the housing affordability thing, and an affordable house is simply one that somebody can afford. It was an infamous statement. It’s dodging around and saying these houses are affordable, we are building affordable housing here—Cameron was always building “affordable” housing. Our current prime minister, Boris Johnson, says he is going to build affordable housing. But when you look at the cost of it, in comparison to a thirty- or forty- or even fifty-percent limit on the bottom half of the income distribution—what half of the people in London “could pay”—they couldn’t even begin to pay it. So how dare they call it affordable housing?

That’s why it’s political. It’s saying you’re “providing affordable housing” when anyone doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation can see that this is complete and utter nonsense. It isn’t affordable in any way.

CM: You write, “Low-income housing projects are usually far too expensive for most of the households they were meant to help.” So who do they help, if anyone? Who benefits from low-income housing if not people who have low incomes?

DP: Nowadays, it is generally the people who are in the higher end of the income distribution. For example, we have a system here called Help to Buy: the scheme is that the government puts in various incentives to make it a bit easier to get a mortgage, to help make mortgage payments a bit lower and so on. The people who have benefited from that are in the five- to ten-percentile group above the point at which the housing dilemma stops. The housing dilemma people are those who just can’t house themselves.

CM: You write, “One definition of market failure is where the operation of market forces leads to a net social welfare loss. This is economics-speak, but it describes the situation in Global South cities where informal, unplanned housing has emerged with very poor or no services, or where outright slums have developed. That housing is very often the outcome of unregulated market forces that may be able to deliver housing affordably to the poor, but it is often problematic and sometimes downright dangerous for the residents’ social welfare.”

This, again, is market failure. Dating back to the late eighties, the term failed state has been commonly used in the news media to describe nations where government has broken down to the point of being unable to provide basic services or acting in any way like a sovereign state. But the term failed market is not one I’ve ever heard in any news media, ever.

Debbie, how often do we mistake a failed market for a failed state?

The way to improve people’s housing in these circumstances is to give them the right to the city, a legitimate foothold within the city, and they themselves will continue to improve their housing by gradual investment, usually by themselves and their families. This is greatly helped if they are given legitimate tenure and services.

DP: All the time. During the twentieth century, the primary way urbanization happened and urban processes of housing worked their way through the world (it’s global) was through people housing themselves in irregular, informal ways. In many cases, that’s outside of the formal market, and it is informal markets where decent conditions are not regulated in any way, because they can’t be. In many cases this has now been regularized. Hundreds of millions of people have been housed now in regularized settlements. That’s been enormously significant. So these are not failed states, these were failures of the formal market to house people. And they are also not failed states, because in many cases they’ve been quite successful, particularly in Latin America.

I would just draw everyone’s attention to one other thing: that the issue of standards and decent housing is something we in wealthier societies frequently forget. You only have to go back just over a century, or even less in some cases, to find situations where people in our own societies were housed in extremely poor conditions, in slums. They were the norm, particularly in the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century. No one, I think, is saying that nineteenth century Britain was a failed state. And our housing was appalling.

CM: You also write, “Probably the most important route to address the market failure at supplying low-income housing, and one that has been of such fundamental significance in many cities of the Global South, has been to legitimize informal housing with legal, officially recognized tenure and the services that then tend to develop. Such housing is often upgraded and then the recognized plot owners can enter into official housing market transactions.”

Doesn’t that legitimize the informal market? Doesn’t that lead to the lowering of standards of adequate housing and endanger residents? How dangerous is allowing the informal market to be formalized? And isn’t informal housing a threat to the formal housing market?

DP: No, not at all. It is the most successful way of housing people affordably that has yet occurred in cities across the world. It’s been phenomenally successful. I’m not romanticizing this, by the way. Lots of people have lived in dire circumstances a very long time before they are regularized, and many, many slums are never going to be regularized (for various reasons, often to do with their location in expensive areas which property developers have their eye on). But in many societies—Africa, Asia, Latin America—this has been enormously successful and people’s lives have been greatly improved.

This goes back to longstanding theorizing from the 1960s and 1970s about how the way to improve people’s housing in these circumstances was to give them the right to the city, a legitimate foothold within the city, and they themselves will continue to improve their housing by gradual investment, usually by themselves and their families. This is greatly helped if you are given legitimate tenure and services. You need clean water. You need sewage. You need schools. You need clinics. You need public transport or at least decent roads. These things have been laid on.

Many societies in the Global South have taken this on board and were doing this very successfully. It’s been chipped away at, again, partly because of this change in the nature of capitalism. There are very nice studies which your listeners can go read by Peter Ward, who is a professor at the University of Austin (and taught me when I was an undergraduate many decades ago), which look at similar types of irregular settlements on either side of the border of Mexico and Texas—colonias as they’re called. One of the many things he says about this is that on the American side of the border, these colonias are deemed extremely bad things; the lives of people are made very difficult and the provision of services to them is done with enormous reluctance. While on the Mexican side of the border, this is not the case and colonias are generally regularized and legitimized—and people’s lives improve because of it.

So the Mexicans are dealing with it better than the Americans are.

CM: You talk about how these broken cities seem to be modeled to turn into economic engines more than what they used to be: places that housed families and a lot of people, centered towards people instead of being economic engines. What happens when a city becomes an economic engine and is no longer a place for people to live?

DP: That’s a dystopian city, isn’t it? Something like Blade Runner. One can speculate about these sorts of things. I discuss the way in which ‘demographic sifting’ is occurring in global cities—I’m talking about the big cities of the world, the ones that are plugged into financial circuits: New York, Mumbai, Sydney, these sorts of places. Fertility has fallen in the most incredible way in such cities—right across Europe as well—so that on the whole, these cities would be shrinking year-on-year were it not for constant in-migration (both domestic migration and immigrants).

The reason for these falls in fertility are very complicated, but it’s partly because of the housing crisis. It’s partly because of the the unaffordability of housing and the increasing financialization of the cities. We can see a situation whereby cities such as these could turn around and say they don’t need families, they don’t need multi-person households, they can get by with single people living in tiny lodgings, because the jobs are here and they will just have to put up with it. But I don’t think that’s what’s going to happen.

That would be convenient, perhaps, for employers and for capitalism, but it’s too neat. It’s too negative a conclusion. Cities are very messy places: they’re politically messy, they’re economically messy and socially messy. This is part of their strength. I think that the trends described in my book can be slowed and changed by concerted actions by urban people. And also it has to be remembered that despite the trends, future housing patterns still are mitigated by the built-in legacies of these patterns of previous ordinary homeownership and of regulated rentals, which mix the picture quite a bit.

I think all these things can be changed. There are lots and lots of people doing their very best to do this. And there is tremendous determination of city populations to fight for their rights to the city. I take hope in that.

CM: Debbie, I appreciate you being on the show with us this morning.

DP: Thank you very much.

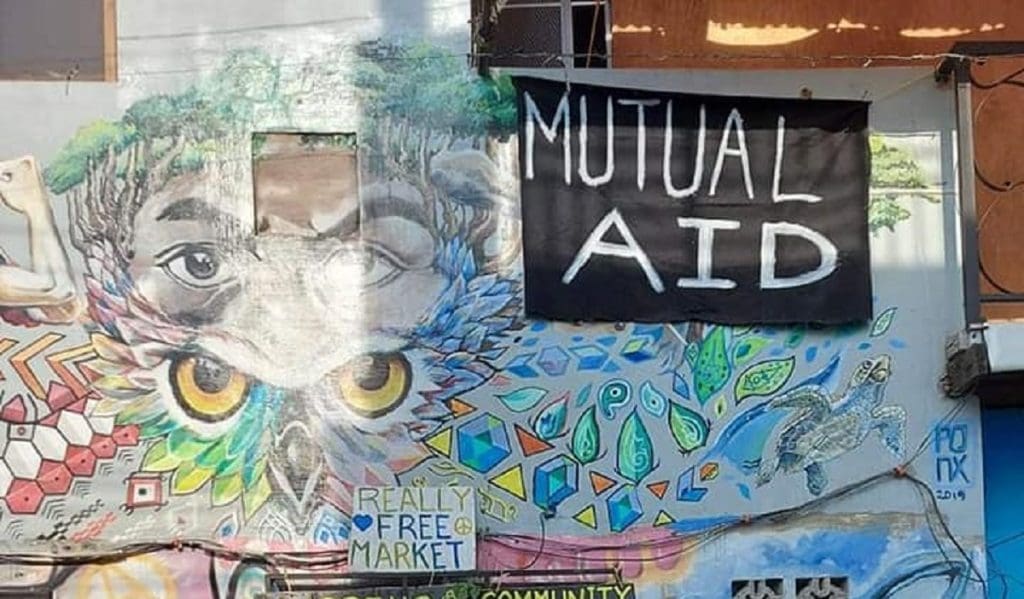

Featured image source: Untergrund Blättle (Switzerland)