AntiNote: the following interview with Leila al-Shami was transcribed from a 15 January 2026 broadcast on Radio LoRa, a community radio station in Zurich, Switzerland with roots in radical autonomous movement. Radio LoRa started as a pirate station during the youth revolt of 1980, informing and inciting the rebels while evading city authorities sometimes by broadcasting from the back of a panel van—the stuff of legends.

In its current form, Radio LoRa continues to serve the diverse underclasses of Zurich with counterinformation and cultural programming in numerous languages. They conducted this interview in English in advance of the “Other Davos” conference in the city, to highlight an emerging counterpower of grassroots internationalism and resistance from the periphery.

Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole conversation:

Radio LoRa: Hello everyone, and welcome. Today I’m very happy to be joined by Leila in the studio. Leila is a British-Syrian activist, writer, and organizer, and a member of the internationalist network The Peoples Want.

In this interview I want to get to know you better and explore what internationalism from below means today, and to you, and learn more about the work of The Peoples Want network.

Thank you so much for being with us today.

Leila al-Shami: Thank you for inviting me.

RL: As I said, you’re a writer and organizer, and you’ve been involved in solidarity work around Syria for many years. Could you tell us a bit about yourself and how you came to this political work?

LS: I was involved in Syrian political activism since the year 2000. When I lived in Syria, I was involved in human rights work there—which wasn’t open work, because human rights organizations weren’t allowed to exist under the Assad regime, so I was connected to opposition movements in Syria. When the revolution started in 2011, I was outside Syria at that time and started to get much more interested in questions of internationalism and solidarity, particularly because the response of the international left to the Syrian revolution fell short in many ways. We failed to get solidarity from a lot of the left, and in fact some sections of the left—specifically the anti-imperialist or “campist” left—stood behind the Assad regime and denied the legitimacy of the Syrian struggle.

So I started to ask a lot of questions. Syrians were coming together, and I met a group of Syrians in exile who were part of a collective in France called the Syrian Canteen, which was an autonomous canteen doing food. We started to bring revolutionaries from all over the world together to try to ask questions about what internationalism should look like in the twenty-first century and learn from each other’s struggles.

We held five festivals over a number of years, and that translated into The Peoples Want network, which is a network trying to connect struggles internationally and put in practice real solidarity from below and mutual aid.

RL: Was there a moment that politicized you?

LS: I remember getting involved in political struggles quite young. When I was still at school, and through university, I was very involved in the anti-globalization movement and against the war on Iraq at that time. But I think the Arab Spring transformed me in many ways. It was transformative for a generation, because it was such a huge revolutionary wave which swept across the region, also at a time when there were uprisings and struggles in other countries: there was a huge struggle in Spain at that time, and Greece; there was the Occupy movement in the US. So it was the Arab Spring that really started my thinking much more about what internationalism means and—the importance of connecting struggles, ultimately, because what we find is that our enemies are very much organized.

The repression of the revolution in Syria was not just national repression, it was international. We had Russia and Iran supporting the regime. We also saw that in 2019 with the uprising in Chile, Israel sent cybersecurity technology; German policing expertise was sent to the Chilean state to repress the movement there. So we really had to start thinking: Okay, our enemies are organized, they’re supporting each other, and we’re in a position of weakness. It’s really time that we get much more organized to make sure the revolutionary struggles to come are not wiped out, as we’ve seen in most of the struggles of the past two decades.

RL: You also wrote about all these things—I didn’t read your book yet, but I hope to soon. How do these two roles, as an organizer and writer, complement each other for you?

LS: I’ve written two books; one I was co-author of is Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, which tries to give voice to the revolutionary movements on the ground in Syria through interviewing people who were involved in the struggle there.

The second text I was involved in was the manifesto for The People’s Want, which was co-authored by nine people from different struggles: from Iran, France, Syria, Lebanon, Chile. This was an attempt to write down the learning that we’d had from the different movements that participated in The People’s Want network. It’s informed by and was developed in discussion with people who were involved in the struggle in Iraq and the struggle in Sri Lanka, many different struggles coming together to try and see what our commonalities are, what we could learn from each other, and what would be useful strategies going forward.

RL: Throughout your work, in Burning Country and beyond, you really emphasize the internationalist perspective, self-organization, and as you said, learning from struggles on the ground. That is also central to The Peoples Want network which you’re part of.

What does the practice inside the network look like?

LS: We just officially launched the network in March last year, so we’re still in the process of building and testing out the structures that we have. But the foundation is to provide a space for liaison, where people can come together and share their experiences and learn from each other, and have some of the difficult discussions that need to be had. Then we’re also working on trying to put into practice mutual aid and solidarity, particularly in supporting movements to build political and material autonomy on the ground and to build connections with other struggles, believing that we will be stronger to resist if we join together.

RL: When reading through the website of the network, y’all speak very clearly about internationalism from below, focused on the people and movements rather than states. How do you define that kind of internationalism?

LS: We define internationalism from below as a response to campism, really, and parts of the left that have believed that liberation comes from above and from putting faith in repressive and authoritarian regimes, believing they provide a counterpoint to US imperialism. What we’ve actually seen is there are multiple competing imperialisms in the world, and the world is no longer divided into two opposing blocs with the US on one side and states like Russia and China providing an alternative. It’s all part of the same shit, really.

We really believe that looking at states as liberators is a total abandonment of the revolutionary question, and we wanted to bring that back and see how people could liberate themselves and start organizing. We believe that’s where a real alternative lies.

RL: You mentioned that the Syrian revolution came up short in the media and in the Western leftist scene. What was missing from existing forms of internationalism and why did you feel like there was a need for a new internationalist network?

LS: In the media, the focus was always looking at Syria either through a humanitarian lens, in terms of the refugee crisis, or looking at Syria through “War on Terror” discourse and the fight against Islamist groups such as ISIS. What was really missing was how people were organizing on the ground.

We need to remember that in the first few years of the revolution in Syria, two-thirds of the state’s territory was liberated from the Assad regime, and what people did was set up in those areas local councils where they completely self-organized themselves to do everything in their communities, whether that was education or water provision.

These are really inspiring examples of what community autonomy can look like; those are things the Western left should have been learning from, and instead it wasn’t aware of those experiences at all.

RL: When talking about community, the first gathering of the network, as far as I know, was initiated by the Syrian Canteen in the Paris suburbs. Why was exile and diaspora such a key starting point?

LS: When the uprisings and struggles were crushed globally, what we saw was a massive exodus of people. People were either killed or imprisoned, or in many cases they had to flee. Because of the problems of organizing across borders, we realized there’s actually a lot of potential for working with diaspora and exile communities where you are in the West.

Many Western leftists might have been working, for example, with Syrian refugees in terms of helping them on the humanitarian level—there were amazing examples all across Europe of people opening squats for refugees to stay in, things like that—but they weren’t actually discussing with them as political actors, as people who actually have a revolutionary experience that people in the West can learn and benefit from.

And they can learn from each other, because for sure Syrian refugees who were in the West have also learned a lot from Western movements’ experiences, which I hope they will take back to Syria and develop the movement there in coming years.

This is a resource, it’s an opportunity for us to get together. It’s not easy for me to go tomorrow to Sudan, but in a lot of Western capitals there are many Sudanese revolutionaries who are there, and I should be learning from their experience, because in Sudan they had an amazing experience also with the Resistance Committees, and building autonomy in the movement there. Those are valuable lessons for us.

RL: Talking about exchange and learning from each other and from different struggles, one of the network’s stated missions is to build a transnational liaison space where you try to connect revolutionaries across ideologies, regions, and forms of struggle. Why is this kind of space so important today—like right now?

I can imagine, but what happens when movements actually sit together and exchange experiences? What could you take away from that?

LS: It’s about learning. Each movement, each struggle learns from what’s come before. There’s so much effort by states to crush our movements, to deny our movements, and we need to preserve the memory. Coming together and hearing tactics that comrades in southeast Asia have been engaged in—it’s completely different forms of struggle than people in Syria, for example, were involved in. It’s very valuable to learn about those tactics: what worked, but also what failed; what our commonalities are, but also what our differences are.

Sometimes there are very difficult discussions because the interests of one movement somehow on the surface can conflict with interests of other movements. We see that very clearly with Syria, because for example Hezbollah was a counterrevolutionary force in Syria; it massacred thousands of people and implemented starvation sieges—but then in Lebanon, Hezbollah is at the forefront of the resistance against the Israeli state. There were some very difficult discussions between Syrian comrades and Lebanese comrades, and I don’t have an easy answer, but it’s really important we recognize those issues and we discuss them and listen to each other.

RL: One of the ways you try to make that exchange happen is Mujawara. Can you introduce us to that concept?

LS: Mujawara is a slightly different format. Our liaison space is mainly through the yearly gathering and also online forums for discussion that we’re having since we’ve launched. But the Mujawara network is an attempt to build a network between autonomous spaces—physical locations. It could be anything: we have farms that have joined, people who are working on food security; we have canteens and media collectives. It is to try to have a place to build territorial roots for the network, where we have places people can meet together and organize.

We have an idea to do every year an international day of action between the Mujawara spaces. I’m not a hundred percent sure, but I think we have one farm in Switzerland, in Basel, which is part of the Mujawara network.

RL: How was the last international day of action?

LS: The last international day of action happened before we formally launched the network. It was a test case following the last festival, at the time of the Israeli assault on Lebanon—which is still ongoing—so we wanted to raise money to send to comrades in Lebanon, to three projects. One was a little farm in Lebanon; and two others were political spaces organizing and assisting people who were displaced.

It was a small test to see what our strength was, and a number of collectives participated in different countries; we raised a few thousand euros. We’re hoping that the next day of action, which will be this summer, will be much bigger now that we’ve launched and we’re publicizing. We’re also calling for people to be involved in that day of action who are not members of the network—so it’s also a way for us to reach out and get to know other spaces that could potentially be interested in joining the network in the future.

RL: How has being part of The People’s Want shaped your own thinking about the Syrian revolution, today or throughout the years?

LS: The main thing has been to not feel isolation. Syrian revolutionaries have felt very isolated; we’ve gone through immense trauma, and it’s very difficult to come from a struggle that not only isn’t recognized but is often slandered or discredited. So to meet people from other countries and other struggles who have been through similar experiences, you find a lot of strength in that.

All the political spaces I’m involved in now, it’s very depressing because we’ve faced so many multi-level crises. Everyone is exhausted, everyone is responding to emergencies, everyone is undergoing immense trauma. The People’s Want is a very different space, for me, because it’s the only political space I’m in where we still have some ability to dream, to think about possible futures and where we want to go. That’s been very refreshing for me; it’s been very healing for me to be part of that kind of group.

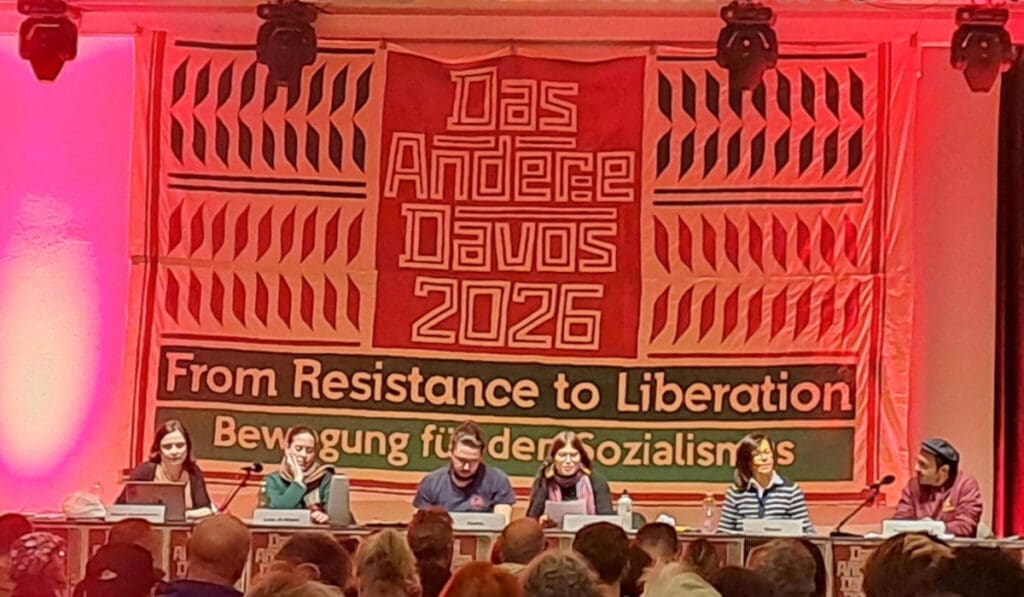

RL: You’re here for “Das Andere Davos” (or “The Other Davos” in English), happening this weekend in response and resistance to the World Economic Forum. Thank you so much for coming, and we’re looking forward to hearing you speak at Das Andere Davos.

The Peoples Want talks about reviving a revolutionary internationalist perspective for the years ahead. What gives you confidence that this is still possible?

LS: I wouldn’t say I’m a hundred percent confident this is possible—but it’s completely necessary, because if we don’t bring in internationalism, we’re not going to survive what’s coming. There are so many crises going on in the world, and we have to see internationalism as a survival strategy.

If you look at the movements that have lasted long term despite relentless attacks—the Zapatista movement, the Palestinian resistance, the Kurdish movement—these are all movements that made internationalism a central pillar of their strategies; all other movements were wiped out. So it’s really important that we start thinking in those terms.

RL: Thank you so much. Maybe you also want to talk about when you’re speaking tomorrow.

LS: I’m speaking tomorrow evening on a panel about Palestine, but I’ll be looking more at regional dynamics. Then I’m on a panel on Saturday afternoon looking at internationalism and solidarity from below, and I’ll be talking a bit more about Syria.

I’d also like to encourage people to check out our website—they can find the manifesto—and to let people know that a German publisher is going to be publishing it in German in the next couple of months, so look out for that. It’s called Revolutions of Our Times.

RL: Thank you so much.

LS: Thank you.

Featured image source: La Fabbrica di Zurigo (Facebook)