We need to stop saying “Just when we thought it couldn’t get any worse…” Who seriously thinks it can’t get any worse? It can and will.

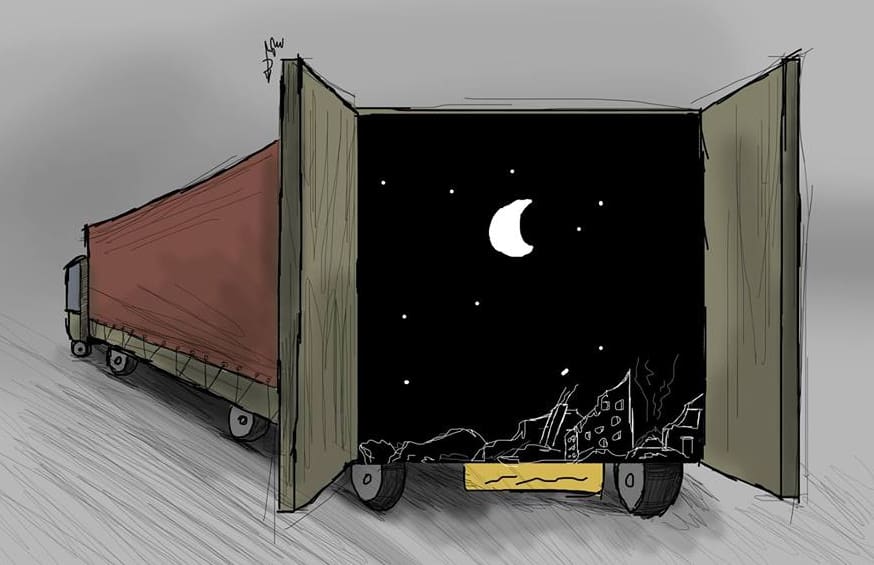

A contemplation of climate change and forced migration may seem like a non sequitur at best and mean-spirited at worst in this moment when society seems on the brink of complete disintegration for different, though related, reasons. Still, these issues must remain in the foreground of our hearts and minds even as we search desperately for ways out of this global death spiral of hatred, suspicion, aggression, and organized murder. Truly contemplating climate change may put the right kind of fear into us—the kind that might help us see it as in all our interest to de-escalate everything. The challenges will only get bigger and more intractable from here, and more so the tighter we squeeze. Love, trust, humility, mutual aid and solidarity will be all that can save us. Seriously.

by Antidote’s Ed Sutton

31 July 2016

It’s Weird Out West

A recent trip to the canyon-riven high desert of the Colorado Plateau fulfilled a longtime wish of mine. I’ve wanted to see that country ever since I encountered Edward Abbey’s writing in my early twenties, but in the last few years of living overseas I have had increasing doubts I ever would. What a relief! I managed a quick turn through before it is no longer accessible.

That might seem like a strange thing to say. I admit it feels strange to say. But I’ve been feeling pretty strange since being out there. I wonder if this is some version of that Earth First!er (or even Burner) cliché: the desert changes you.

Probably, actually. But it’s not all bad. It was truly an intense and edifying journey. The vastness of that inhospitable country is as sublime and terrifying as advertised—its history of defiance in the face of human attempts, large and small, to master it (or even just to describe it) is already well documented. I can only confirm: even with my visit to those grandiose badlands already a couple months behind me, it has been difficult to audit, fully or neatly, the deep impression they made; it is all too big, too sad, too beyond. Now back “home” in Europe, what I feel, primarily, is disoriented.

This article is an attempt, maybe a foolish one, to sort some of that out. Ironically, the explicit purpose of the trip (for me, anyway; I was not alone) was self-care—and actually it mostly did the trick in that regard. On the Colorado Plateau (and, as we know, in any arid “waste,” hot or cold), it is impossible to avoid a heightened awareness of expanses—of both space and time—as well as of one’s own smallness and terminal vulnerability, which opens new and healing avenues of reflection. Simply put, deserts are mystical as fuck. But enough about that. Foreboding, grief, anger: these were also part of the bargain, not something I can say I’ve ever brought back from an “escape into nature” before.

The first and most graspable source of these odd feelings was perhaps the odd weather. In the evening on our first day at Horseshoe Canyon, thunderheads filled nearly every horizon, and winds at rim altitude picked up, strong and constant enough to flatten our tent against the ground. Feeling like total amateurs, we packed it up in order to spare the cheap stakes a job they would probably give up soon; in the process we nearly lost it over the rim in the gale. We had to shout to hear each other. Though the sun was still bright on our bare shoulders, the temperature had dropped ten degrees in a minute. It was impressive.

The next day down in the canyon we ran into another hiker who had apparently observed us in our struggle with the tent. She asked how we had fared overnight once the storms really struck. Fine, thanks. I asked if it was normal weather for this time of year. “No, this is apeshit,” she said. “Definitely the wrong time of year for this much rain. Monsoon season was weird last year too. Came too early, stayed too long.” I would hear the same from several other desert people over the next few days; this pattern of evening storms continued daily for most of our trip.

And even though this can all be regarded as merely anecdotal, we know already that, generally speaking, things are getting weird out west. California is well into its fifth year of unbroken, intensifying drought; wildfires there and in Alberta this year have been called unprecedented in their scale and destructiveness. Record high temperatures, the works.

Now add in the fact that the ongoing water crisis can only be expected to accelerate. Nevada’s government sells water rights to Nestlé for a song while fracking waste poisons entire aquifers in California; the drought drags on; rationing is imposed (unevenly); more and more farmlands and irrigation systems, exhausted, drop dead; the depleted reservoirs behind dilapidated dams that have kept ill-considered megalopolises like Phoenix and Los Angeles alive for decades are failing and will not be replaced, ever, with anything.

This might sound like raving now. But facts are facts: there’s not enough water out there for all these people, and certainly not if people use it in such morbidly idiotic ways. We’ve known this particular fact since the first scientific expeditions into the Colorado Plateau and beyond almost 150 years ago, in the late 1860s (of course, the people who lived there before their violent expulsion by whites knew it, too, but nobody asked them). Major John Wesley Powell, in his 1876 Report on the Arid Regions of the United States, warned how little water was available in the newly “acquired” territories west of the hundredth meridian and how difficult as well as vital it would be to manage it properly. Whoops.

Yes, In Your Backyard

There’s just not enough water out there. This is one of several hard facts that we should take for granted when trying to imagine and plan for the future, something neither Powell’s contemporaries nor later generations did, minus a few visionaries who were mostly regarded with deep suspicion or suppressed outright. But now, and I really mean now, we are beginning to suffer the consequences of our forebears’ deluded, damnable avarice (seems a tad unfair, doesn’t it?). I would say the chickens are coming home to roost, except a lot of this land won’t be able to sustain chickens or much of anything else, and won’t be home to anyone anymore, perhaps soon, perhaps in our lifetimes. We need water to live. Ask the folks in Flint, or in Darayya.

That is probably a little manipulative. But why not connect these things? It may help us understand what we are facing. Part of the empathy deficit in the West regarding Syria has to do with a self-protective othering of Syrians under siege and in flight, a purposeful failure of imagination. We “cannot even conceive” of their suffering, because it could never, ever happen to us. I’m here to tell you that it could. Will. God forbid. In some instances it already has, albeit on a lesser scale.

I don’t want to construct a false equivalence that erases the genocidal terror being inflicted on Syrians by a deranged dictator with, let’s face it, no incentive to stop his systematic campaigns of siege and starvation, rape, torture, and mass murder. But in many cases where this terror has failed to uproot Syrians too defiant or destitute (or both) to leave, it can be the facts of an impossible life that succeed. Where life is literally impossible—no food, no water, no shelter—people take mind-boggling risks to get to a place where it is less so, even if only marginally (that is, unless flight is also impossible. Then, as Francesca Borri concludes in her book on Aleppo, Syrian Dust, all there is left to do is die).

Understood this way, it is the height of racist self-delusion to regard this kind of suffering and displacement as “inconceivable” in the United States. We have already seen it, in another climate change-related event no less, just over ten years ago, and you’ll know I’m referring to Hurricane Katrina. If present trends continue, this kind of suffering and displacement in North America and other heretofore “peaceful and prosperous” regions of the world—whether the result of sudden catastrophe or a more gradual deterioration of conditions—is not only conceivable, it is inevitable. Only the scale of it, the number of people directly or indirectly affected, how fast and to what extent, is uncertain.

On the way out to the back country, my companion and I stopped through one last settlement, a town in eastern Utah whose only remaining purpose, it seemed, was supplying tourists like us. We speculated about its original reasons for being there; frontier trading post, extractive industry, military—at any rate, the town has seen better days. Along the main drag, two thirds of the sun-bleached storefronts were closed, many boarded up, radiating unintentional cowboy kitsch and menace.

I thought of Riace, the now mythologized coastal town in Calabria, Italy, which was given new life a decade or so ago by the sudden arrival of refugees on the beaches and their immediate incorporation by townspeople into the aging, failing community. Of course, relocating Kurds or Somalis to Green River for the purpose of revitalization wouldn’t be particularly practical, even if it were palatable to the remaining locals; resettling Central American refugees there would make much more sense, if only US-Americans’ narrow political bandwidth could accommodate such an idea.

But even then, it seems much more likely that the current residents of that desert town and others like it will be the ones forced to pull up stakes and seek greener pastures in the near future. Building and sustaining human communities takes resources, and trucking in resources to a place like Green River—to say nothing of goddamned Las Vegas—where there aren’t any just lying about, not even basic ones, is not going to be something that even a delusional “economic powerhouse” like the United States will be able to continue much longer. Edward Abbey, doing Major Powell one better, was always right, and is more so now than ever: human beings, in our current mode of social organization, do not belong out there and should get out and stay out.

Great, that’s settled. But what will happen when they do get out? It won’t be a willing departure, in all likelihood; it may begin with a trickle and grow over decades, or it may be quite sudden, the result of a shock. But we should start trying to imagine what this might look like so we can plan; it could be important. As I have written before, migrants will be this century’s revolutionary vector. What migrants do, who they are, why they left, where they end up, how the people “there first” receive them, and what newly acquainted strangers collectively build together will determine political outcomes both regional and global—and may even determine whether or not humans continue to persist as a species on planet Earth at all. No joke.

Now the ranting and raving has really begun! Not even. Because I’m still referring to migrants right now in the third person, as a “they.” This, to me, is the biggest rhetorical blindspot in much of today’s even progressive media. Because the migrant is you. The problem with the current discourse in developed countries around climate migration is the same problem as with the discourse around climate change itself: it is talked about as distant, elsewhere, happening to “them,” they who, as luck would have it, we don’t give two fucks about anyway. So we can keep doing what we’re doing.

But Pachamama does not discriminate. Racist Western systems of outsourcing and exporting misery to “lesser” countries (and confining it to “lesser” communities at home), stern and robust as they may be, will be no match for the sublime forces of climate change and cascading ecological destruction that they have contributed to setting in motion. Too hot is too hot, too dry is too dry, submerged is submerged, poison is poison, and nobody gets much of a say in it, no matter what color their skin is or how much money they have. You can’t keep it away. Facts are facts. Dead land is dead, and people can’t live on it. And Saskia Sassen, among others, has pointed out that a lot of the land that capitalism has already killed is in its own tackily appointed living room, in some of the most populous states in the US. Europe is also not immune. Why would it be?

So the climate migrant is you, wherever you are. You and your children and your neighbors and their children. I’m not trying to scare you; this is not an attempt at whipping up mass doomsday hysteria. It would be a lame attempt, too verbose, and either way, panic is the last thing we need right now. No, this is more of a surrender, a resignation to the facts: we will not be reversing, preventing, or containing the earliest destructive impacts of globalized capitalism and climate change. These impacts are already resulting in widespread loss of viable human habitat. And neither imagined geographical or material advantages nor technological patch jobs will protect anyone from them.

Keep Calm and Spread Anarchy

Therefore, another hard fact we should take for granted as we plan for the future, and the main one I want to emphasize, is that as a result of water depletion, land death, droughts, superstorms, flooding, fires, and social conflicts springing from all of the above, a lot of people in a lot of places will suffer; many may die; many will have to move or die; and forced, desperate migration, with no prospect of return, will be a constant, probably escalating feature of our global society, affecting everyone in one way or another, sooner rather than later.

This is also a point that Sassen has made and I have stolen and tastelessly embellished. However, her first instinct as a response is to call for institutional recognition of this new kind of migration (which, again, is happening already) and the new kind of subject that it presents: a person for whom the current international legal regime around refugees and migration does not have a place, and for whom even the term ‘climate migrant’ is not entirely apt, since the lands many used to live on are not being killed by climate change per se but by extractive exploitation, contamination, and misuse. That’s fine. Recognition is the first step. But I think, and I’m sure Professor Sassen also knows, it’s going to take more than that. Or rather, it depends on what kind of recognition and by whom.

Indeed, as Rebecca Solnit has pointed out in her book Paradise Built in Hell and elsewhere, it is often the established institutional machinery, the powerful (this can mean governments and business interests; police, military, and private security forces; as well as non-governmental humanitarian organizations), who in their efforts to control and contain “chaos” in disaster situations end up making things much, much worse. Solnit, drawing on a growing body of scholarship around disasters and disaster response, calls this elite panic. Through this lens it is easy to imagine official recognition of new, uncontrolled migratory flows amounting essentially to their classification as a threat to be combated, a problem to be solved with the tools and methods of security and authority—which simply compounds human suffering, adds insult to injury, and leads to further conflict. We need look no further than the so-called Balkanroute for a glaring and still-present example of how this works. [Previous Antidote Zine articles on the topic here]

There is another side of the coin, however, which is the main argument in Solnit’s Paradise and which was also in widespread evidence on the Balkanroute (at least before the jackboots of panicky, racist authority crushed all but the most compliant—or most audacious—projects): spontaneous, improvised mutual aid and solidarity among strangers. Encouragingly, this same impulse found expression during and after the aforementioned wildfires in Alberta incinerated a tenth of Fort McMurray, nearly emptying the city of residents. There was much fanfare about one group in particular who rushed to the aid of evacuees: Syrian refugees, of all people! Similar stories were breathlessly reported after recent flooding in France and Germany. Of course, this should not have surprised anyone. The only fitting response to this lopsided empathy, frankly, is shame.

Alert readers will sense that I am inching towards a call to drop all our defenses, drop all our fears, to open ourselves to love and kindness, to listen to and learn from people who we are encouraged by security hysteria to distrust—the other, the transient, the stranger, the dispossessed, the loser—because it is they who have often faced unspeakable adversity comparable to that which we will all likely face, and, you know, sharing is caring and so forth, and the answer isn’t to change institutional structures first but to change ourselves. Well, okay. I admit I do find these kinds of moralistic, emotional panaceas appealing.

Whether they are effective is quite another matter. Homo sapiens‘ long and bloody history, in defiance of thousands of years of its own competing but fundamentally similar philosophical and faith traditions, should be enough to convince us that simple exhortations to empathy or solidarity or other righteous virtues will not save the world. It is doubtful, frankly, that anything we say or do, individually or collectively, will save humanity from itself, and there is more and more nihilism floating around insinuating that maybe it’s better that way.

Paradoxically, though, it may just be that this kind of resignation will ultimately be what saves us. That is, if any exhortations are necessary or appropriate at the moment, they are negative, de-escalatory ones: do less, let go, stop it. Now, this goes against an awful lot of my own political and emotional instincts (this article is, after all, the result of a tumultuous year that has caused me to call these instincts—so familiar, so well-worn, so comforting—into question). And, I should watch my step, because it could also be interpreted by those engaged in liberatory struggles that they should give up, resistance is futile. That’s not what I mean.

So let me be more specific. On the one hand, and most obviously, these de-escalatory exhortations ought to be directed at the powerful and panicky, in which case no revolutionaries or advocates for radical change of any kind will find much wrong with them; in fact, these kinds of slogans, always popular, continue to proliferate and resonate. Don’t shoot. Stop killing us. Leave it in the ground. My personal favorites are the ones that tell authoritarians to fuck off altogether. Sometimes, though rarely, those even work! Que se vayan todos.

On the other hand, more people than just the powerful should also do less, let go, and stop it sometimes. One way this is true is related to the “Que se vayan todos” phenomenon; in order for authority to be convinced enough of its own irrelevance to actually fuck off, we have to be truly convinced of its irrelevance too. In other words: stop automatically believing in established institutions’ competence, beneficence, or importance; stop appealing to them for anything, least of all their help, that’s not what the tools they use are for; stop reflexively trusting, admiring, and deferring to officials, cops and soldiers, bosses and celebrities, anyone whose power derives from wealth, naked force, or tradition; stop buying their narratives about who the “bad guys” are and who we should be afraid of, who wants to kill you. Nobody wants to kill you. Except maybe them, actually. That’s why they seem to see threats everywhere: they assume everyone ticks the way they do. Reminding oneself that they are wrong already has a calming effect.

There are many things we could let go of that would help pave the way for a less conflictual, more solidary transition into the arriving era of unplanned mobility, instability, and awkward encounters among strangers in strange lands. Chief among them are expectations of material comfort and the way we tend to regard amenities, conveniences, technologies and other pretty, easy things as talismans of status. That is to say, living standards and conditions are likely to “deteriorate” for many people—or, alternatively, they ought to if we want to survive—and not only must we learn to let go of most if not all of this noisy, poisonous crap and the complex, costly and destructive systems that deliver it to us, but we must decouple the idea of having dignity from the trappings of “being dignified.” We’re all going to get dirty and hungry and probably upset sometimes. This should be okay. People who react to this in others with disgust and judgment—not to mention fear and aggression—will have, and deserve, the hardest time.

The upside of this relative material deprivation, having less stuff, is that nobody has to make it anymore. That’s part of what I mean by “do less.” It is the entire overblown, exploitative consumption-production cycle that will be the death of us all, if grasping fascist violence doesn’t accomplish that first, and we need to dial way down on both ends of it. Around this time last year I already attempted to formulate one approach to doing this, and since I’m starting to run a little long I will spare you the rehash. In short, quit your bullshit job.

Let’s go back to Utah. Not literally, of course. That would be a long journey, especially from here in Europe, now that we have stopped burning fossil fuels and gotten rid of our most murderous machines like automobiles and airplanes. And despite the unseasonable rain, there’s no water out there; we’d only have what we can carry. Let’s stay where it’s safe, where we belong, as long as it’s safe and we belong. No, thanks to other (also quite destructive) technologies, I can take us back there in our imaginations with the help of this photograph. These paintings, down in Horseshoe Canyon, are estimated to be around 6,000 years old. Slow down, let go, and contemplate that for an afternoon. There is, in all seriousness, no better use of your time.

In memoriam: Baron Von Scrohlen

Rock hard, ride free my dear brother.