Transcribed from the 11 February 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Those with the money to inundate us with a certain form of reality have a much greater strength than those of us who do not. We are not smarter than how we feel. Associations can be made in us when things are repeated to us on a daily basis.

Chuck Mertz: This past November’s election can best be understood when we view culture as a weapon used by the powerful to attain, maintain, and expand their influence in an unprecedented way that will continue to grow and have a greater impact on us as we move into the future.

Here to tell us how art is culture and culture is power—especially in the hands of the powerful—curator and critic Nato Thompson is author of Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life. Nato is a contributor to the collection of essays What We Do Now: Standing up for our values in Trump’s America, which also features writing by past This is Hell! Guests David Kohl, Elise Hoag, George Lukoff, John R. MacArthur, Bill McKibben, Trevor Timm, and Katrina Van Den Heuvel.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Nato.

Nato Thompson: Glad to be in hell with you.

CM: You write, “As every artist knows, Plato argued that artists should be banned from society. A believer that we live in a pale shadow of a world of perfect forms, he felt that the arts were dangerous imitations, three degrees removed from the world of Ideal Forms. He feared that the arts could stir the passions of the populace, muddying the objective rationality required in the republic. Plato’s opinion certainly runs counter to the operating logic of society today. The United States is a consumer society awash in the products of culture.”

But there is this idea that we have turned our back on an age of rationality, an age of reason, and have moved towards an age of affect, an age of feeling. How much does being awash in our products of culture lead us to a society that more and more relies on feeling rather than reason? Is the culture industry to blame for any end of reason?

NT: Yes. But we have to be careful—culture industry is a big thing, particularly in the decentralized, internetty world we are in, where it’s not just CBS programming us now, or ABC, or just big ads, although certainly that’s all part of it. But we are all to some degree participating in a certain level of cultural production on a very micro level.

CM: I want to make sure that people understand: when you talk about art, you write how you “consider movies, online programming, video games, advertisements, sports, retail outlets, music, art museums, and social networking all a part of the arts, as they all influence our emotions, actions, and our very understanding of ourselves as citizens.”

How much does that art lead us to vote what we might see as against our own self-interest? Because many on the left believe that Trump supporters unwittingly backed a candidate who was against their own best self-interest.

NT: Trump, with the maneuvering of Steve Bannon, was able to leverage a lot of affect. A lot of fear. As we know, Steve Bannon is in fact quite specific and articulate about the uses of fear and anger as a strategy to mobilize a public. So it was very much on the surface throughout the campaign, and it’s very much on people’s minds.

But I don’t want to focus exclusively on Trump, insomuch as this was going on pre-Trump. Certainly we can go back all the way to Nixon. The culture industry has been a part of everyday life. I’m 45 years old; it’s part of my everyday meal. I’ve eaten video games, advertising, television, film, radio, music, rock and roll, punk rock. It’s a big part of my consumer diet as a person of America, and I don’t want to paint it simply as a Trump thing, because it happened throughout Obama, it happened during Bush, and it happened during Clinton as well.

CM: Do our products of culture, no matter who is employing them (and in view of how they are appropriated by politicians), determine elections? Do they maybe even determine what our beliefs are that make us support one candidate over another? Do those things determine our elections more than any serious discussion of policy?

NT: It is a huge part of the game. Here’s a testament to it: if you watch a presidential debate, often the pundits on television will discuss it in terms of the “optics,” of the way the conversation is framed, how such-and-such a person “came off.” With Hillary Clinton it was, “Was she relatable? Did people sympathize with her?” These ways of discussing debates show—it’s very clear, and we understand it intuitively—that affect is more important than the actual points being made in a debate. They think about it in terms of how people feel about them. And they say that not because they are being cynical, but in fact because there is a clear realization that this is the most effective form of politics.

CM: You write how you “do not seek to uncover a cultural conspiracy that puppetmasters deploy culture to brainwash us.” Instead, you write how you “want to explain the ways in which those in power have to use culture to maintain and expand their influence, and the role that we all play in that process.”

While it’s not a conspiracy theory, how much do we realize culture is being used to maintain and expand the influence of those who you call “the powerful”? How much are we coerced, rather than openly and honestly convinced? How much is this power grounded in coercion?

NT: Tremendously. There’s a long history on the left of basically saying people are delusional, but they never point the finger back at themselves. As you know, Noam Chomsky put together a book called Manufacturing Consent, which is basically detailing the way the powerful kind of brainwash the masses. There’s a long history of that. Thomas Frank, the writer of What’s the Matter with Kansas? asking why people in Kansas vote for the GOP when they had decimated farming with big agribusiness.

So there’s a long history of that. But I don’t want to get to the point of just saying it’s them out there who are deluded, because right now we’ve got a giant push on Trump, and everybody—in cities, particularly the blue cities—are acting self-satisfied. They are saying, “We were never for Trump. We were never deluded.” But let’s face it: we went through eight years of Obama, where wages stagnated, where the gains from the recession recovery went to the upper one percent of America. This is just to say everybody on all sides of the ideological spectrum, unless you’re the wealthy, are caught up in some sort of delusion. Because real gains for everyday people are just not happening.

CM: You bring “the traditional arts, theater, visual arts, dance, and film into conversation with not only the commercial arts but also public relations and advertising. In this way, we can position this more broad definition of art as something that has a potentiality for being both deeply coercive and absolutely powerful. After a century of cultural manipulation, it would be naive to discuss art without simultaneously discussing the manner in which art is already deployed by power daily.”

But most people probably don’t see these displays of art as art, but ads. What impact do ads have on the audience when the audience doesn’t see them as art? What do we miss in our understanding of this power of influence when we see these things as not artistic?

NT: Often we think of art as stuff that’s on museum walls, or maybe a video or some graffiti. Just to say, most Americans—and it’s reasonable—categorize art as something very different than the giant spectrum we’re familiar with from video games to television to radio to film.

It is useful to put these things into conversation with each other, though, because then we can appreciate the strategies that are being used by all of them. Because certainly we understand that an advertisement is somehow coercive. People are not watching Budweiser commercials unaware that they’re being sold Budweiser. But what is important to understand, and what advertisers know, is that it doesn’t actually matter whether you know that or not. You’ll still have an impression put on you.

The thing that advertisers know is that there’s a power in scale. When people talk about impressions, or people talk about clicks—think about “clickbait” in the internet age—it is about tying art to conditions of scale. They understand something very important, which is that we are not smarter than how we feel. Associations will be made in us, if things are repeated to us on a daily basis. That’s why “the powerful,” those with the money to use this approach, have a much greater strength than those of us who do not. Because they can inundate us with a certain form of reality that we will inevitably come to accept.

CM: You write how art and life have in fact merged. Have life, art, and power all merged more than ever before? Are we seeing a combination of those three things being held by the powerful in an unprecedented way?

There is an arms race in the war for attention.

NT: I would say absolutely yes. The trick of it all is that in a globalized world, economies are much more consolidated. Companies are not just US-based but globally-based. I don’t want to smooth that over, because if we think about economics a little bit geopolitically, of course there are competing forces that aren’t on the same team. Apple and Microsoft, for example, aren’t exactly friends. We get that. But at the end of the day we are subject to very large forces with a lot of power to shape the narrative.

On the flipside, the internet—for good and bad—has opened up the conversation profoundly. Social networking is an extremely powerful device. I would put it on par with the printing press in terms of its power to remake the conversation and to change how people think about themselves. And that force is both being used by power but also has a potentiality and is being used by those who are disempowered.

Just like the printing press was able to destabilize the Catholic church, today the internet is able to destabilize, to some degree, governments and different kinds of consolidated economies.

CM: If culture is a weapon, then who has control of it? Is there a disparity in who has access to these weapons? And can we stretch this metaphor even more? Is there always some kind of arms race when it comes to employing culture as a weapon?

NT: Just statistically speaking, there are those who have a lot more power when it comes to using culture, like I said. Nonetheless, it’s also quite destabilizing. It is a profound arms race. If we think of it in terms of people trying to get our attention—or, for that matter, all of us on the internet trying to get each other’s attention—and think about the spread of “fake news,” or the hyperbolic way news is told today, from CNN to alt-right news sites, we see there is an arms race in the war for attention. And fear, often, is the easiest way to get it, but there are also other tools available.

I think the arms race is a good way to describe what we are in the midst of, and to some degree we are all participating in it, though at different levels of capacity and power.

CM: But, as you point out in your book, it seems like culture is not only growing, and growing faster than ever, but it’s exponentially growing. Is the consolidation of the power to influence through culture growing as well? Are both consolidation and the industry itself growing at exactly the same time? Because if that is happening, that would suggest that people who are making non-commercial art are getting pushed more and more out of the picture.

NT: It’s a complex world, and there’s a lot of room for niche industries and niche participation, and quite frankly, just to go to the election: this election was so wild not only because of Trump—obviously, there was also someone like Bernie Sanders. Both of them spoke in a way that four years ago would not have been considered serious. Bernie Sanders basically talked about Scandinavian social democracy. Trump, off the cuff, would dismiss military families, POWs, every race in the book, handicapped people, and still managed to be a serious contender and then become president.

I just say that because we do live in an age where the bandwidth, the spectrum of the discourse, is getting broader, and that is destabilizing a certain center of power. From the center right or center-Republican to the center left or center-Democrat: all of that is being destabilized. There is a loosening up of power, but at the same time, as we can see, in that vacuum that is opening up, the mobilization of simple, classic historical things like xenophobia, fear, and misogyny have rushed to the fore, and have a lot of leverage.

CM: You write, “Power is visible in the hands of our elected officials as often as it is hidden in a package of inanity. The many forms of power in our world have sophisticated approaches to reaching that very needy, fearful, and social creature we call ourselves.”

How much is this power bringing the very needy, fearful, and social creature we call ourselves to the fore? Are we more needy and fearful today because of the ways in which power uses today’s culture and its technologies?

NT: Yes, on a few levels. Certainly we are more needy, because economic disparity makes people profoundly needy, on a very basic level. But at the same time we are needier emotionally, partly because of the growth of the culture industry. That is to say: being bombarded by people using our emotions to get us to do things has a psychological effect in general, and it makes us paranoid. My book could have just as easily been called Just Because You’re Paranoid Doesn’t Mean They’re Not After You. There is a certain way that all of us have to navigate cultural space, and it inevitably has side effects on how we relate to the world.

The sense of being anti-establishment, or paranoid against power, is both real and, simultaneously, a destructive result of our relationship to culture.

CM: So there is a cumulative nature to constantly being bombarded with advertising that focuses on our most vulnerable emotions, the ones that are the easiest to manipulate. How much does that define our view of reality today? How much is our worldview shaped by the emotions that ads constantly provoke?

And does this kind of messaging keep those feelings, those nerves raw? That is: they are the easiest to provoke, and they are ready to be provoked.

NT: It does make our nerves raw. All of us are in a collective coming-of-age of the Social Network Internet Machine, and we’re starting to understand that it affects us emotionally, as a global world, together. And it has mood swings. People are starting to realize they can’t look at their feed all the time because it’s so exhausting. We understand we can’t just email angrily; we’ve come up with a term called the troll, which frankly is in all of us—it’s not something out there, we all have troll-like behaviors. That is just to say, yeah, I do think it makes our nerves raw.

It also means we have to think about our relationship to mass communication and technologies in a way that’s therapeutic and healing, just so we have some clarity and space to not be emotionally reactive.

CM: Enthusiastic emotions, and spreading fear, seem to work better than when culture is deployed with truth, rationalism, and a message of hope. So with culture becoming more and more powerful, are all signs pointing not toward a hopeful future but one of fear?

NT: I don’t know. It’s hard to say. I wake up every day with a different answer to that. At times one would say the inertia is headed towards fear, with Trump. But at the same time, I’ve seen a lot of progressive movements happening. That women’s march was quite exciting. Everybody heading to the airports to push back on the executive order on immigration was extraordinarily enthralling, with real positive messages. So I’m not without hope right now.

As much as this hopefulness is emotionally laden, there is a sense of truth in it. It’s just murky and muddy. All of us are probably pretty nostalgic for Obama—but that said, think about Obama coming into office. That was in the post-Bush era. That was the post-Gulf War era. And he came in on a campaign of hope and a campaign of Yes We Can, Change You Can Believe In, these kind of Pepsi-commercial adages. People were mostly in the mood for that, and I’m sure they’re going to be quickly in the mood for that again.

Culture is very effective, and affective, but we need to know that we’re trading in the tools of what could also be a Tea Party handbook. During Occupy Wall Street, the movement got the most viral when people saw videos of cops beating up kids.

CM: You write about the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s in a really fascinating way, in a way that most people do not think about the culture wars: you write from the perspective of an artist living through those times. I’m not an artist, but throughout that time I was hanging out and living with a lot of artists, so I remember a bit of it.

How were the culture wars different for artists than the non-artist public? What might the non-artist public not understand about what happened with the culture wars that we could learn from your perspective as an artist?

NT: Well, the classic way people understand the culture wars is that it was the silent majority versus the freakish city artist. There was Jesse Helms, who took as his subject of ridicule a photographer named Andre Serrano, who had an artwork called Piss Christ, where he’d taken a crucifix and dipped it in urine. Quite frankly, during that time, if you were in New York City, this was not an outrageous thing to do. But that artwork, to the eyes of Jesse Helms in North Carolina, looked like the most outrageous, blasphemous thing one could ever do.

But Jesse Helms was quite savvy. As much as it looked like he was picking on “Culture,” or artists (which he was), the bigger thing is that he was mobilizing culture. He was being an artist himself insomuch as he was mobilizing vast resentment and concerns about religion and blasphemy and sexuality.

That was a true lesson, and in fact it has been a page taken out of the conservative handbook many times. After that, for example, they went after Robert Mapplethorpe, who took photographs of homosexual sexuality. So conservative Christian rightwingers actually got to gay-bash on television while simultaneously enjoying talking about lurid sexual details a lot.

CM: We recently spoke with Vyvian Raoul, the editor of Dog Section Press, which published the book Advertising Shits in Your Head, about the impact of advertising and the subvertising tactic being deployed against it by groups like London’s Brandalism or New York City’s Special Patrol Group.

You write about the “precarious terrain” of using culture for activism. What would you warn those kinds of organizations in the subvertising movement about the precarious terrain of using culture for activism?

NT: It’s just good to be aware of what you’re doing. Culture is very effective, and affective, but we need to know that we’re trading in the tools of what could also be a Tea Party handbook. During Occupy Wall Street, the movement got the most viral when people saw videos of cops beating up kids—what activist circles often describe as “riot porn.” That kind of lurid, violent film—which is very affective, emotionally—circulates really fast throughout the internet. Also, while Occupy was good because it was pushing up against the banks, “the banks” as a term was also so abstract that it often grabbed libertarians and the rightwing as well as the leftwing. It was a bit of a grab-bag (which is good, and I’m pro-Occupy), but we also have to understand it was trading in some very loose cultural machinery.

At the same time, too, Black Lives Matter—which is such an important movement—seizes on film of cops killing people of color. You’re in Chicago, you guys are very well aware of that. That kind of footage is so powerful, and terrifying, and awful. But it really got people off the couch and into the streets—that’s the good part. The other part of it, though is nevertheless that it trades in a certain kind of shocking footage that is hard to get your hands on and moves very quickly. That’s just to say: it’s not the same as a calm, objective political discourse. It’s very different.

CM: You write how you see the culture wars as a kind of turning point in the fight for power when it comes to art and culture, and that after the culture wars things seemed to change when it came to art and power. You write that your book is about “artists, motion, affect, and manipulation. The very tools key to the cultural shift I describe are, after all, tools artists have deployed for centuries. These tools have been captured and co-opted, and this, in turn, has had an impact on how artists work.”

How were the arts co-opted in the wake of the culture wars?

NT: If you think through the nineties and the last decade, slowly but surely you begin to see the arts move into spheres that we might not be familiar with. Suddenly, the subject of gentrification, or the articulation of “creative cities” by someone like Richard Florida, really looked at the arts as a part of the urban fabric. And suddenly there were real estate developers that were giving housing to artists. Galleries became a way to mobilize into neighborhoods, and suddenly there was this weird relationship between the arts and real estate.

On another level, there was an organization like Starbucks. I get into that in the book: Starbucks and the Apple Store and Ikea. Suddenly corporate culture, building on this relationship between the arts and real estate, begins to see civic space as something that needs to be creative and social, so these tools of the arts were really embraced. Apple computers is so art-friendly, it really embraces the individual and the radical.

That shift imposes some real dilemmas for artists. Suddenly it’s not enough to do art in and of itself, because often it is being utilized or instrumentalized for larger purposes. Whether it’s where you live (when it’s inadvertently gentrifying a neighborhood) or the place you show your art (when you show in a gallery but it ends up being some sort of propped up space to generate a new economy in the region), it becomes very difficult for artists.

This shift in the arts is interesting in the ways that underlying political economies of place become a part of the more radical left position of art. It’s not just what you make; the conditions in which you make it are also important.

CM: You write, “Understanding the power of association and the uses of emotion can explain a US election better than the lens of capitalism.”

Did this past election deliver us into a new era where emotions, more than campaign fundraising, determines elections? Did it just exacerbate that situation? Or is victory through the power of culture now going to be the preferred political strategy over traditional fundraising and media spending? Because Donald Trump certainly didn’t spend the most amount of money in this campaign.

Let’s face it: frankly, most Americans are broke. We can unite around that. There are ways to find common ground that would be much more powerful than simply thinking that all Trump supporters are idiots.

NT: Oh my gosh, that is so true. All of us lived through it. The cameras could not take their eyes off of Trump, period. By the time he got elected, and the major news media sat there lamenting and complaining, every American had to ask: “But you kept your camera on him the whole time! What idd you expect to happen?”

It’s because, of course, the nature of news has been getting more hyperbolically driven. If a camera ever took its eyes off him, the internet world would just fill the void. There is this kind of expediated inertia of the famous press adage of “If it bleeds, it leads.” It’s interesting that Roger Ailes was involved in the campaign, because certainly Ailes is a master of media. He was head of Fox until he had that sexual misconduct trial (which was probably long overdue). Nevertheless, he had a great saying, which was: “If a politician is talking about peace in the Middle East and then falls in the orchestra pit, what do you think the news will cover?”

That is extremely insightful. Because Trump is a man constantly falling in the orchestra pit.

CM: You write about the “Love Trumps Hate” catchphrase: “The phrase is catchy in a Yes We Can sort of way, as though the world of meaning must now be reduced to memetic jingles, a warfare of hashtag virality. In a sort of passive aggressive way, the message seems to want to overtly state, with clear pride, ‘I am for love, and some people are for hate.’ Well, okay, if that makes you feel better. But the phrase smacks of emotionally manipulative mass identification.”

But Nato, what’s wrong with that? Can making people feel better and getting them to identify together as a group be a constructive step toward a sustained opposition to the Trump presidency? Or do you believe emotionally manipulative mass identification is not what’s needed most right now?

NT: I would do a two-pronged approach. I saw the women’s march—which was great—and there were a lot of people out in the street who had never marched before, and there is a profound education that occurs when someone is finally so politically frustrated they actually head out and join other people. So I think it is a good thing.

That said, I don’t want the lessons of this election lost. If everybody in cities is patting themselves on the back and blaming the hicks in the suburbs and exurbs, then we’ve learned nothing. There’s much more going on than our own ability to relate to people we live around. The people out there in the exurbs and suburbs have a different sense of the world, perhaps, but maybe it’s not as different as you think. It’s a simple thing, people say it all the time, but hard to achieve: it’s easier to march down the street than it is to take a car ride out to the suburbs among the strip malls and big box stores. But it is important that we nevertheless give a sympathetic view to the ways we are being pitted against each other.

Because let’s face it: frankly, most Americans are broke. We can unite around that. There are ways to find common ground that would be much more powerful than simply thinking that all Trump supporters are idiots. If we go down that road, it’s a mistake. It’s ethically dubious. And while it might be good for us to mobilize in the short run, in the long run a certain kind of class consciousness needs to move beyond our simple urban geographies.

CM: How important is it during the age of Trump to not have an us versus them approach, while simultaneously working hard in opposition to whichever of Trump’s policies you may oppose? How difficult is it to do both?

NT: I think it’s totally doable. Frankly, it just depends how you divide up your time. If you look, for example, at the electoral college, this country cannot push back on a conservative agenda if it’s going to stay inside cities. Clearly the map is not there. The irony of it is that all the money is in cities, and yet it’s the cities that think of themselves as the working class voter base. So there’s some untangling that has to happen in the Democratic Party about the legacies of neoliberalism. At the same time we need to find ways to get in touch and mobilize with a lot of people who have been left out of the economic, globalized age.

CM: In your essay in What We Do Now, entitled “Artists and Social Justice, 2016-2020,” you write, “With the election of Donald Trump, a tangible sense of doom has permeated America, and the urgency to act, to find solace and community, or maybe even to hide, runs deep. Artists can help us with all of those reactions. And above all, they can create work that challenges the forces that brought the situation into existence, and will continue operating throughout Trump’s presidency.”

What kind of art would challenge that situation? You write how artists can fulfill the roles that journalists have fallen short of doing. What kind of art can help us through this age of Trump?

NT: It’s a big grab bag. There are a lot of needs. I don’t want to be completely utilitarian, or imply that everything has to be a push against the Trump agenda, because I also think emotionally we need space to just reflect and rejuvenate and think, to think about love, think about melancholy, think about dreams, and be poetic. I’m not one to ever think there’s not time for that. The soul needs constant feeding.

At the same time, if we look at Depression-era America, with the WPA: at the time there was a real movement towards social realism, a real sympathy for the impoverished, for the working class, depictions of what it means to be a person in this country, and I think we could go that direction. I mean that for everyone from the Walmart workers to the call center workers to the immigrants picking strawberries out in California to the people flipping houses in New Orleans. There are a lot of people who are struggling with their jobs all over this country, across every demographic. It’s good to see that, and artists have done that, historically, but it’s powerful to be able to see yourself in the mirror and to know that not only do you exist, but your existence is in fact tied to others’ in this country.

CM: Do we, in the end, live in Plato’s world of art’s dangerous imitations that undermine any objective rationality we need for an efficient and effective republic? Are all of our problems art’s fault?

NT: The problem is that Plato got it wrong. Because it’s just who we are. It’s not art’s fault. It’s just who we are. We’re very clumsy, fearful, intimate people who really need to be humble in the way we approach governing our lives and making justice happen.

CM: Thank you so much, Nato, a fascinating conversation.

NT: A real honor, thanks so much.

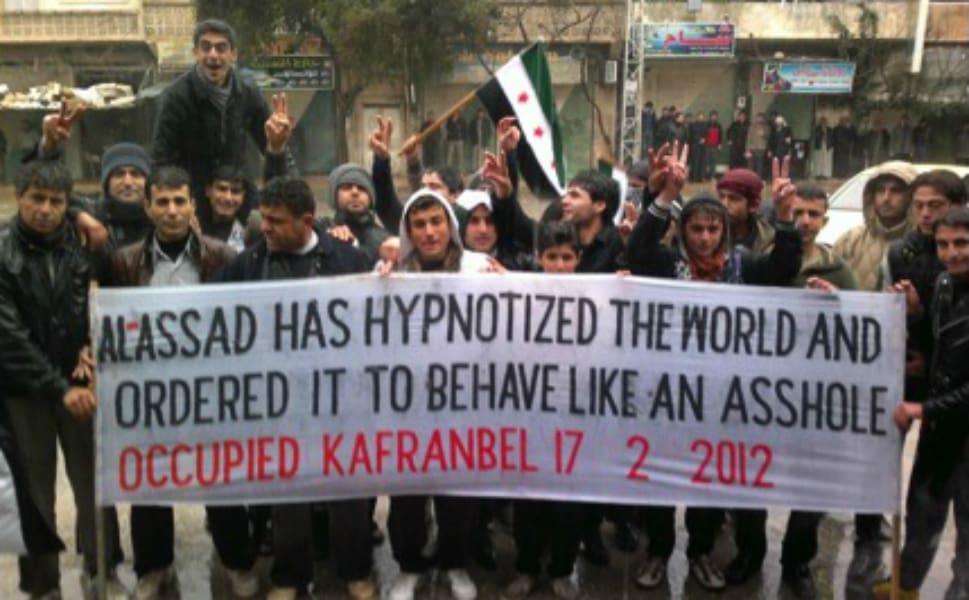

Featured image: just some manipulative riot porn from Oaxaca 2006