“Disobedient Movement,” Rescues and Repression in the Mediterranean

by the Alarm Phone network

6 February 2018 (original post)

Alarm Phone Eight-Week Report for 11 December 2017 – 4 February 2018

On 30 December 2017, the Alarm Phone was contacted by travelers in the western Mediterranean Sea. After having paddled for more than ten hours, they were rescued by the Spanish search-and-rescue agency Salvamento Maritimo (SM). While they were in distress at sea, our Alarm Phone shift team stayed in close contact with them, and forwarded information about their location to SM until it was confirmed that they were on board a rescue vessel.

This was the last Alarm Phone case of 2017. Two days later, on 1 January 2018, we received our first case of the new year. A group of travelers had arrived on Samos Island in the Aegean, but were not able to leave the beach on which they had landed. Although we were not able to establish direct contact with them, we alerted the Greek coastguard to the group and could later confirm that they had safely arrived in the camp on the island. On the same day, we were alerted to two other emergencies in the Aegean region—fortunately, both boats were rescued to Greece.

From October 2014 (when we launched the Alarm Phone project) to the end of December 2017 we worked on a total of 1,925 emergency cases in the Mediterranean Sea. In 2017, a year that saw tremendous changes and transformations in the Mediterranean space, we were engaged in 155 distress cases.

In all Mediterranean regions, unauthorized sea crossings continue. On 16 January 2018 alone, about 1,400 people were rescued in eleven rescue operations in the central Mediterranean. In total, about 8,000 people have crossed the sea in the first four and a half weeks of this year. While this shows very vividly that many are still trying successfully to cross Europe’s maritime borders even under very adverse conditions, Mediterranean migration has decreased overall in the past two years, from the record-breaking 1,015,078 people in 2015 to 362,753 people in 2016 and 171,332 people in 2017. But while the number of sea crossings came down by half from 2016 to 2017, the number of deaths did not. 3,119 deaths were recorded last year [after 5,079 in 2016].

2017: A year of radical transformations in the Mediterranean

The year 2017 was marked by several developments that severely impacted migratory escape through the central Mediterranean: the unabated militarization of maritime space by the EU and its member states; the ongoing attempt to criminalize and delegitimize NGOs conducting search-and-rescue (SAR) operations in the Mediterranean; and intensifying cooperation between the EU and its member states with Libyan coast guards.

In February, the European Council’s Malta Declaration announced the enhanced cooperation with Libya as a key priority, thereby emphasizing the importance of Libyan forces in EU migrant deterrence efforts. In the same month, a Sicilian prosecutor publicly announced an investigation into alleged connections between SAR NGOs and smugglers, and the executive director of Frontex declared in a newspaper interview that smugglers profited from the presence of NGOs close to the Libyan coast. Together with seven other organizations, the Alarm Phone network decisively rejected the accusations by Frontex and the Italian prosecutor.

From May onward, Libyan coast guards were involved in several clashes with SAR NGOs, starting with Sea Watch and later also involving ProActiva Open Arms. In August, the Iuventa vessel of Jugend Rettet was confiscated in Italy and thus unable to continue its vital work. In November, up to fifty people lost their lives when Libyan coast guards interfered with an ongoing SAR operation. Nine of the thirteen Libyan crew members had been trained by the EU military mission “EU Navfor Med” and their vessel had been donated by Italy.

The criminalization of NGOs, coupled with the increasingly aggressive behavior of emboldened Libyan coast guards, have had dramatic effects: a year ago, about a dozen NGO assets were patrolling to rescue lives in the Mediterranean. Today, only Sea Watch, ProActiva Open Arms and SOS Mediterranée are continuing this work, while an increasing number of people who are trying to escape the inhumane conditions in Libya are pulled back. According to UNHCR, more than 15,300 people were captured by the Libyan forces and returned in 2017. According to an estimate by the IOM, even more than 19,000 people experienced this practice. And despite the uproar that a CNN report on conditions in Libya caused across Europe and beyond in November 2017, there is no willingness to change course. In 2018, as of 26 January, about 1,430 people have experienced these cruel effects of EU containment policies.

Many of those who find themselves (again) in Libya are supposed to be ‘humanely evacuated’ by actors that carry out what the EU border regime desires: deportations carrying a humanitarian cloak. Some of these cynical returns are organized by international migration managers, such as the IOM, or private actors, such as the Migrant Offshore Aid Station [MOAS]. In 2017, more than 19,000 people from 25 countries were repatriated from Libya—a dramatic increase from the 3,000 who were returned in 2016. The plan now is to repatriate up to 10,000 people over the first two months of 2018.

2018: Grim outlook for the central Mediterranean

Europe’s strong desire to close the central Mediterranean route that we have seen this past year is set to drive EU policies and initiatives also in 2018. Already the roadmap set out by the European Commission and the most recent European Council conclusions from December 2017 make clear that priorities will remain an intensified cooperation with Libya, including ‘assisted voluntary returns’ from there, and the overhaul of a range of EU policies and directives dealing with unauthorized migration. Within the first half of 2018, the European Commission plans to adopt new proposals on the Asylum Agency (a strengthened version of the European Asylum Support Office [EASO]), Eurodac [fingerprint database], the Qualification Regulation, the Reception Conditions Directive, and to formally open negotiations with the European Council on the Dublin Regulation. In addition, it calls on member states to contribute more to the pools of equipment and personnel that the European Border and Coast Guard uses for their operations, and aims to increase deportations conducted by them by at least twenty percent compared to last year.

While we will have to wait for the negotiations between the various EU institutions to come to an end to see the full results of the initiatives currently underway, it is clear that most of them will be aimed at making access to Europe even more difficult, while worsening conditions for those who are already there.

Given the radical transformation of the Mediterranean space that we have observed and taken part in over the past years—in terms of both unprecedented movements as well as unprecedented forms of border violence—we cannot predict how this year will develop, and where we might be when we look back a year from now. And yet, the path that we are currently on seems quite clear, at least according to the EU and its member states: the reinforced militarization and surveillance of the Mediterranean (as the new Frontex operation Themis already demonstrates); heavier investments in border enforcement (including the further strengthening of Frontex, more surveillance, more border technologies); restrictions on movement through third country allies (including the funding, training, and equipment of border authorities of authoritarian regimes); the accelerated privatization of border control to security corporations; the further precaritization of migrants already present in Europe through restrictions on their mobility, rights, and dignity; as well as accelerated deportations, including those branded as ‘voluntary returns’ or ‘evacuations,’ through which vulnerable populations are returned to war zones and regions ravaged by civil conflicts and/or poverty.

As always, these border enforcement measures will mean that migratory journeys will become increasingly lengthy, costly, and deadly. The dying has already begun in the new year—321 fatalities have been officially counted, but there are many more who have gone uncounted. On 6 January, about 64 people died after their rubber dinghy capsized off the coast of Libya; 86 people were rescued. A day later, during large-scale rescue operations in the central Mediterranean, two women were found dead. On 9 January, between fifty and a hundred people are estimated to have gone missing in a shipwreck off Libya—only sixteen people seem to have survived. In mid-January, Salvamento Maritimo stated that a boat drifting off the Canary Islands was carrying five dead bodies. Two others who had attempted to swim ashore also lost their lives. Around the same time, the NGO SOS Mediterranée found an empty rubber boat in the central Mediterranean—nobody knows what happened to its passengers. On 20 January, two dead persons were retrieved in a rescue operation carried out by Salvamento Maritimo ten nautical miles west of the Alboran Island in the western Mediterranean. ProActiva Open Arms reported three deaths on 22 January, including one three-month-old baby. Three dead travelers were also discovered on a boat that was returned to Morocco on 23 January. On 27 January, SOS Mediterranée reported a particularly tragic emergency situation: “After having been at dawn a direct witness to the interception of a rubber dinghy in international waters by the Libyan Coast Guard, the Aquarius was mobilized for the rescue of a sinking rubber boat in international waters off the Libyan coast. At the end of the day, 98 people were pulled to safety. Two women died and many more are missing.” On 2 February, about 90 migrants, mostly from Pakistan, died in a shipwreck off Libya. Two days later, up to 47 people drowned off the coast of Morocco.

Mobilizing against repression

Given these continuous atrocities at sea, it remains crucial in the new year to mobilize against the forces that construct a deadly obstacle course for those who want to, and need to, escape. In light of the vicious criminalization campaign against activist networks and humanitarian actors engaged in Fluchthilfe [aid in fleeing] and/or rescue, what is required is a strong solidarity front that speaks back when activists and rescuers are turned into smugglers and criminals. Not only in Europe, Turkey, and Northern Africa, but everywhere. In the Mediterranean they use the sea to kill; in the US-Mexico borderlands, the desert. We voice our solidarity with the activists of the No More Deaths network that provides water and basic care for travelers attempting to cross the desert between Mexico and the US. In January, after publishing video footage of the US Border Patrol cynically destroying water gallons, some of the activists have been arrested and now face legal charges.

We as the Alarm Phone network promise to do what we can also in the new year to support disobedient movements through the sea. We have recently updated our ‘Risks, Rights, and Safety at Sea’ leaflet for the central Mediterranean crossing between Libya and Italy. We have also released the second series of ‘Solidarity Messages for those in Transit,’ a video project that aims to reach travelers along their migratory trajectories in order to support them in navigating the many border obstacles and traps that the EU and its member states have erected in their paths. This time, we have three videos in which survivors of sea journeys pass on advice, spoken in Amharic, Somali and Mandinka, with English subtitles.

Lastly, save the date and join us for the We’ll Come United Parade on 29 September 2018 in Hamburg!

Developments in the western Mediterranean

22,900 sea crossings were counted for the western Mediterranean route in 2017. In addition, 3,856 people successfully jumped the fences of the Spanish enclaves on the Moroccan mainland, Ceuta and Melilla. This means that the number more than doubled in comparison to 2016, when 12,923 successful border crossings were counted. These arrivals in 2017 mark a record, surpassed solely during the peak of crossings to the Canary Islands in 2006, when nearly 38,000 travelers arrived in Spain. These rates seem to be continuing in the new year. In January, 2,307 crossed into Spain, of which 1,501 arrived by sea.

The rising number of crossings is partly due to turmoil in the Moroccan Rif region that created departure opportunities from the Moroccan west coast, and partly due to rising migration movements from Algeria. Moroccans and Algerians account for about forty percent of the successful border crossers to Spain; the remaining sixty percent are mainly from Western and Central Africa. The number of Algerians attempting to cross has been rising since summer 2017, and intensified cooperation in migration control has been discussed between Madrid and Algiers. Since the end of November, about 500 travelers who arrived in Murcia, mainly Algerians, have been brought to a detention facility close to Malaga. Deportations back to Algeria already started via ferries from Valencia, Murcia, and Alicante.

Already in the first week of 2018, on 6 January, a group of 209 people managed to jump the fences of the Spanish enclave Melilla—four persons were hospitalized. Also in Ceuta there were several attempts to jump the fences: on 12 January, around fifty people were stopped by Moroccan forces. Only one man managed to climb the five-meter-high fence at the Tarajal II border gate and enter the Spanish city. In two other attempts during the night from 14 to 15 January, a total of 350 people were pulled back by Moroccan forces. The Moroccan Association for Human Rights [AMDH] reports ongoing raids in the forests around Nador. On the morning of 10 January, the camps in Bolingo were attacked by the Moroccan Forces Auxiliaires and around 35 men and women were arrested. We often see these raids carried out in the aftermath of a larger successful crossing into Spain, showing that Moroccan authorities continue to function as Europe’s watchdog and frontier guard.

In the meantime, the criminalization of Helena Maleno—a Spanish activist who has for many years assisted travelers and alerted Salvamento Maritimo to people in distress at sea—continues. On 10 January, Maleno appeared in court in Tangier over allegations that she had colluded with people-smugglers. She was further questioned on 31 January, when she was interrogated for an hour and a half about accusations made against her by the Spanish police back in 2016. It has not yet been decided whether and when she will be called in for a trial, but if the Moroccan court decides to find her guilty of human smuggling, she is at risk of receiving a lifetime prison sentence.

Developments in the Aegean

In 2017, according to UNHCR, 29,718 people crossed the Aegean Sea and reached one of the many islands. Given that 173,450 people made it in 2016 (following 856,723 in 2015), this constitutes a drastic decrease, a consequence in large part of the EU-Turkey deal from March 2016. And yet there are still steady and continuous movements across the sea. 1,732 people have arrived on the Greek islands in 2018 as of 4 February. While there are days without any boats, on others we see several landings, as was the case on 28 January when about 201 people arrived in one day. The composition of the traveling groups is remarkable and seems to signal a trend also in other Mediterranean regions, with more and more children and women taking to the sea. In the Aegean, in the first month of the year, nearly forty percent of passengers were children, and more than twenty percent women.

Many of them have arrived on Lesvos Island, where Europe’s hotspot remains an inhumane and dramatically overcrowded detention facility (for a detailed account of the situation on Lesvos, read the new report by Musaferat). However, every few days now, one hundred to two hundred people are being transferred to the Greek mainland. Some containers, delivered from the mainland, have been set up as shelters for those staying outside in tents, presumably not least due to the increased media attention that has been drawn to the conditions inside the Moria camp. Deportations to Turkey have not occurred over the past few weeks—but rather than being a sign of hope, this seems to be the consequence of a new deportation strategy that allows for deportations also from mainland Greece. This would suggest the reversal of an implicit agreement following the EU-Turkey deal of March 2016 that ‘merely’ people from the Greek islands would be subjected to deportations to Turkey.

As a recent report by Harekact has noted, the number of such ‘forced’ deportations is significantly lower than the so-called ‘voluntary’ returns from Greece to countries of origins through the ‘Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration’ program of the IOM, which is mostly funded by the EU. Between June 2016 and the end of December 2017, 2,100 people were forcibly deported to Turkey, while in the same period of time, 9,089 people were ‘voluntarily’ returned to their countries of origin. Why would migrants who have endured the risky crossings then decide to be returned? Harekact’s investigation reveals that the inhumane detention conditions compel many to sign up for the IOM program—it is simply a way to shorten their time in detention and avoid detention in Turkey. “Many people are literally broken by the unbearable living conditions in Europe’s refugee camps,” and the returns program offers a way out. During their participation in the program, however, “many migrants face detention and serious physical and mental harm.”

City Plaza in Athens, the best hotel in the world, offers the exact opposite: accommodation for refugees, run independently and with support from solidarity networks. They have called for an international day of protest on 17 March 2018, under the banner “Stop EU’s Dirty Anti-Migration Deals.” They write: “On the occasion of the International Day Against Racism and two years after the signing of the EU-Turkey deal we will again take to the streets on 17 March! Let’s fight together against the EU-border regime! Struggle with us for a world without nations and borders!”

Reprinted with permission; lightly edited for clarity by Antidote

The original report includes link citations that we have not reproduced; please go there for a full list of references as well as incident summaries for each of the seventeen distress cases the Alarm Phone network was involved in during the eight-week period covered here.

Also, please consider donating to the network via PayPal.

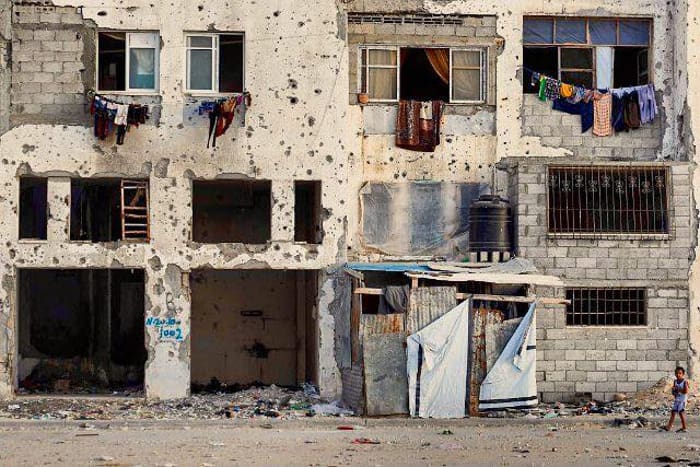

Featured image source: Alarm Phone (Facebook)