Transcribed from episode #7 (“Theorizing Syria, Egypt, & the Arab Spring and Analyzing the Impact on Palestine”) of Irrelevant Arabs and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The massive revolutions that have happened across the Arab world have drastically restructured regional, domestic, and international power relations. So Trump is not creating a new agenda, but he’s part of new, different power formations that are forming in this new era.

Mustafa: Tonight we have two special guests here to talk about Palestine: Mariam Barghouti, a writer and commentator on Palestine who is from Ramallah and currently visiting New York; and skyping in from Chicago we have Jehad Abu Saleem, a PhD student at NYU whose research focuses on the Arab perception of the Zionist project and the history—both social and political—of the Gaza Strip; along with your favorite irrelevant Arabs: myself, Loubna, and now Malek Rasamny, the third irrelevant Arab, who is a director currently working on a very interesting documentary shedding light on the lives of Native Americans on reservations and Palestinians in refugee camps around the world.

Tonight we are finally doing the long-awaited Palestine episode. Of course we’ve been wanting to do an episode on Palestine for quite some time; this will be one of many, because it’s a topic that cannot be covered in forty-five minutes.

Welcome to our studio, guys, and thank you for skyping in.

Mariam Barghouti: Hi.

Jehad Abu Saleem: Thanks for having us.

Malek Rasamny: Thank you guys. I’d like to get into internal politics within the West Bank and Gaza, especially because the Palestine activist scene here [in the US] is always really focused on the American point of view—which of course is important given America’s huge, horrible role in this conflict—and the internal politics gets missed.

Something really simple to begin with is Trump. There is a big debate—and it’s a complicated debate, it could go both ways—where there are some people who say that it’s the same policy, no matter what, from president to president, from term to term. It’s the same policy that America always has: unilateral support for Israel. At the same time, there’s an argument that Trump represents a new fascist wing within generalized American support for Israel.

Two big moves he did that are a departure from America’s standards are the unilateral recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and also the defunding of UNRWA. Those are two big moves that I don’t know would have happened if he weren’t president. But it’s an interesting debate. So I wonder what you guys think are the continuities and the differences in terms of a Trump presidency.

MB: With Trump being president, everyone is focusing on this being new, a new form, and on things that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. But everything he’s been doing has had the infrastructure already laid out. If it’s declaring—or recognizing, rather—Jerusalem as the the Israeli capital: it’s already been there, even in American regulations. It’s just that presidents have been signing waivers over the years. This wouldn’t have been possible had Israel not had the infrastructure. It was treating Jerusalem as its capital anyway. All its meetings, conferences, and anniversaries are all held in Jerusalem. That’s the bigger issue. It’s not this presidency finally recognizing it, but what made it possible for him to do so.

JA: I agree with you. The infrastructure was already there, and in order for Trump to gain leverage within the US political arena he capitalized on some alliances and relationships in Washington that involve this already-existing tendency within American politics to support Israel unconditionally. This existed during the Obama administration and before. This isn’t a huge departure.

The new thing is that this US administration—we all know that Trump himself does not come with creative ideas in any sense, let alone when it comes to Palestine and the situation there—is operating in a new geopolitical and regional context in the Arab world. This touches on the importance of this episode tonight: we are speaking about the connection between the situation in Palestine and the larger context of the Arab world.

But before we get to that: from the perspective of someone who lives in America but is not an American so has an observer’s perspective, I want to look on the flipside. There is an opportunity in the Trump era for Palestine organizing, and for building more power in the US for the sake of Palestinian rights and the Palestinian narrative. Trump is making it really hard for liberals to get away with not supporting many issues, and Palestine is definitely one of them. If we look at the Jewish-American community, is no longer easy for people to be liberal on everything but Palestine, especially in light of Netanyahu and Trump’s close alliance, which happened even at times when the Trump administration included antisemites.

So there is a positive side to having Trump in power—I don’t want to put it that way, but this is one of the things that has been happening, and it’s an exciting moment because we can see how the discourse on Palestine and how the circle of allies is expanding because of Trump.

MB: Definitely. I don’t think we would have had the same reaction from the international community had the same decisions come from Obama. People would have accepted it more. But because there is this understanding of how racist and absurd Trump is, people are also recognizing that his decisions towards Palestine are also absurd. Had it been Obama, for instance, people would have been more accepting, just because of his general approach to foreign politics.

MR: I agree; it exposes the interior contradictions within the liberal Zionist rhetoric. I know from growing up in America that support for Israel is more of a Democratic than a Republican cause. It’s obviously a cause across the board, but it has been particularly associated with the Democratic Party, whereas support for Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states is more of a Republican oil tycoon thing. It has all obviously been part of the same general policy. But that narrative is breaking down in unprecedented ways, as Trump’s general rightwing extremism is being associated with Zionism—and that’s a good thing, that’s a truthful thing.

Many people who speak in the name of Palestine cannot see what’s happening in Syria without using the American lens. They can’t see what’s happening in the Middle East without seeing where the Americans are standing so they can take the opposite side. This is really dangerous.

The idea of an administration that is one of the more openly antisemitic administrations we’ve seen is also the most pro-Israeli—that contradiction could be productive, to see that the most antisemitic people are actually part of an administration that’s extremely Zionist and exposing that.

But I’m interested in what Jehad was talking about earlier, because I hadn’t even considered that fully: that Trump’s actions towards Palestine and Israel are not just a product of his unique administration’s outlook but part of a changing geopolitical situation in the Middle East that is also part of the Arab Spring. The massive revolutions that have happened across the Arab world have drastically restructured regional, domestic, and international power relations. So Trump is not just creating an agenda, but he’s part of new different power formations that are forming in this new era.

JA: Let’s go back to 2011. In the conversation around the Middle East and the Arab world and also Palestine, from now on, we, as activists, as organizers, in our attempts to understand and make sense of how we got to this point, with all the things that are happening on the ground, it’s important for us to separate 2011 as the moment that sparked a defining trajectory, and we’re living the implications of that moment now, be they positive or negative. We are still living 2011.

2011 was a moment in which class struggle in our part of the world expressed itself in its ultimate revolutionary form. There were people demanding social justice, demanding rights, demanding dignity and respect, and demanding the fall of a regime. When people said Ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam, they meant the fall of a regime that has excluded them from politics, that has been treating them in brutal and violent and coercive ways, and that had put the majority of Arab people—whether in the so-called pro-resistance camp or the so-called moderate camp—outside politics.

For us Palestinians, our most important asset has been the support of our fellow Arab brothers and sisters all over the Arab world. This was a moment in which these people came out and asked for their rights and asked for more representation, and basically demanded these states become theirs. They have been outside these states for a long time.

Of course, the response of regional players—the regimes themselves, Israel, the West, Russia, and Iran—was not welcoming. Reading the history of how these actors responded to the Arab Spring, none of them has been excited about Arab people asking for the end of an era in which they have been marginalized in every aspect of their lives.

How is this related to Palestine? We Palestinians have been passionate for decades, hoping for a moment in which these regimes—which have played an important role in intercepting our very liberation by limiting the potential of the Arab people themselves and have played a mostly destructive role when it comes to Palestine—would be challenged.

I don’t recall a time when there was an Arab regime that played a positive role when it comes to Palestine—even those regimes that claim to support Palestine rhetorically. Take Iran, for example. In 2011, when it was politically and morally impossible for Palestine’s largest resistance faction to support Bashar al Assad, Iran (and Assad himself, and Hezbollah) blackmailed that faction. They conditioned their support of that faction on its operating against the will of its base and against what most of its members viewed as the right, proper, moral, and rational thing to do—that is, to take a stance against Bashar al Assad.

Loubna Mrie: I just want to give some historical background for people who don’t know that there’s a big split in Palestinians’ point of view when it comes to the Arab Spring, and Syria specifically. Many Syrians—me included—ask the question all the time: why are so many Palestinians siding with the Syrian government? When I was giving a talk with you at Hunter almost six months ago, I was surprised by the many weird questions we got implying that we—Syrian activists—work closely with Israel and that we’re tools of imperialism.

All of us here can try to find other root causes of this problem, but in my opinion the main problem here is that many people who speak in the name of Palestine cannot see what’s happening in Syria without using the American lens. They can’t see what’s happening in the Middle East without seeing where the Americans are standing so they can take the opposite side. This is really dangerous.

Also, Mariam, you said that having the Trump administration in power might be good [for movement building], but at the same time this movement today is really split. And it’s not organized. We witnessed what happened last year at the national Students for Justice in Palestine conference, and it was really sad. This is the biggest gift that you can give to Zionists.

MB: There is a huge division, especially when it comes to Syria. One reason is because so many of these dictatorships and regimes have monopolized the Palestinian cause to draw legitimacy: “We support Palestine so everything we do is okay.” But even more of this is identity. Everything we see is very centered around the politics of the US. It’s unfortunate, because it makes us lose sight of who we are outside of this grand scheme. And it’s a form of inferiority complex, where we are nothing without this counterpart in the US and the West.

MR: A lot of activists, both in the non-Arab world and in America especially, take these dictators’ rhetorical support for Palestinian at face value. People don’t understand the role the Syrian government played with the Palestinian movement, and the conduct of the Lebanese civil war is greatly misunderstood in terms of the fundamentally detrimental role they had in stymieing an advantageous agreement or position for the PLO at that time.

Why is it necessary for a regime that claims to be anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist to treat its people like shit? It doesn’t make sense. Both morally and in terms of our interests, we Palestinians should be in favor of having decent Arab states where people are respected and not haunted by the brutality of regimes.

JA: I want to refer here to Ghassan Kanafani’s famous 1936 revolutionary pamphlet. Ghassan is mostly known for his literary works, but his political and theoretical works are unfortunately not translated into English, and few people even read them in Arabic. Ghassan talks about three forces that hamper Palestinian liberation. He describes the dialectical relationship between those three, and when he talks about them, he does not prioritize one over another, but talks about them equally. These three forces are: the Zionist project itself as an imperialist project; Arab regimes standing in the way of Palestinian resistance, intervening in Palestinian political affairs, and challenging Palestinian independence; and reactionary Palestinian leadership.

The relationship between these forces is dialectic, and they reinforce each other either directly or indirectly. For Palestinians to be liberated, the work for liberation has to happen on these three fronts: by resisting Zionist imperialism and occupation; by promoting Arab liberation and emancipation; and by building a different reality in Palestine in which we do not operate under patriarchal, misogynist political structures reliant on aid, like that of the PLO now or other factions that have basically become job creation programs.

We can talk about the history of how bad the Assad regime was, but I really want to move on with this conversation to theorize the 2011 moment and provide an analysis for the impact of 2011 on Palestine and Palestine’s impact on that moment. Then we can talk about the roots of these toxic discourses around the Arab Spring within certain specific Palestinian circles that are supposed to be the most supportive of revolution.

This is a point that every Palestinian and friend of Palestinians can agree on: Palestinian liberation cannot be achieved without Arab liberation and emancipation. Arab liberation and emancipation means that Arabs can have states that respect their citizens, states that include their citizens in politics, states that do not limit the potential of their citizens. Here there comes a question. Why is it necessary for a regime that claims to be anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist to treat its people like shit? It doesn’t make sense. Both morally and in terms of our interests (it we want to talk about interests), we Palestinians should be in favor of having decent Arab states where people are respected and not haunted by the brutality of regimes, are handled with dignity, have access to resources, have access to politics and access to the state, and can live like normal people.

MB: There are all these regimes, and they suppress their people—but it’s not new. There is the Palestinian Authority, which is supposed to represent the Palestinian people but is also a dictatorship. But they got away with it for so long because the PLO claims that it’s fighting for Palestinian liberation.

All these dictatorships have this Palestine rhetoric in common. It’s a cause that’s so easy to capitalize on, and it makes it even easier to get away with suppressing their own people. But I don’t know why everyone is surprised when it comes to all these dictatorships. The very Palestinian leadership does it. It’s the easiest go-to scapegoat argument.

Also, I disagree with you about 2011 being the ultimate revolution. For me, honestly, I think it was practice for something bigger that is yet to come—years, maybe decades from now. It wasn’t the ultimate revolution. I think it’s just the first step in something bigger.

MR: What people misunderstand about the Arab Spring is that, whatever the results of it have been (whether or not it was “successful,” and it hasn’t been in many cases at least in the present moment), it was a giant disturbance. It was a genuine earthquake in the Middle East. Six different countries, with six different kinds of politics, with six different geopolitical alliances, all rocked by massive movements of people who, regardless of the political discourses they were employing, had the same idea.

It shattered the illusion, it shattered the power structures, and we don’t know what will happen, because we don’t know how these structures—geopolitical alliances, and Sunni and Shi’a, and Saudi and Iran and Israel—are going to respond. We’re still watching it unfold in real time. The problem is that people want to be so sure of things that they can’t step back with some modesty and recognize this giant rupture and then recognize the unforeseen consequences that could still happen as a result. That’s why people whose rhetoric or worldview made sense before 2011 now just seem totally foolish and contradictory.

Sisi is friends with Hezbollah and he’s the most pro-Israeli Arab dictator. Figure that one out. It’s a new world.

M: The biggest testament to what Jehad was saying is the treatment of Palestinian people within these countries that claim to support the Palestinian cause.

LM: In Syria we even had a Palestine Branch [of Air Force Intelligence] created just to torture Palestinians.

M: Aside from that, the Palestinian people who have been living in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan have all been crippled by these governments. A minority of them have broken out, but the vast majority of them have been living in poverty. They haven’t been allowed to find the means to fight for a Palestine they want to revive. The Syrian government treated Syrians, Palestinians, and everyone within its territories with the utmost brutality under dictatorship. And then, when the revolution started, this dictatorship started killing its own people under the pretense that they—an entire nation of people—were working for Israel.

Back home it’s such a completely different reality: there’s oppression; we don’t want to live in oppression anymore, so we’re going to fight it. It’s hard for people here to imagine what it means for an entire nation to rise against its own government. They’ve never experienced it.

MB: It’s the go-to argument. Even in Palestine in 2011. The first thing that everyone used against Palestinians was saying that they have a Western agenda, that they’re spies, that they’re CIA. This is the go-to argument, because it’s the easiest. And again, it’s looking at the Arab world through the lens of the US, looking at the Arab world through the lens of the Western community and their power. It’s a reason why we keep getting defeated—or at least that there’s this defeatist perception. It’s because we can’t see ourselves outside of this scope.

But imagine if we do! Imagine if we do see ourselves outside this scope. All these little arguments will seem banal, irrelevant.

JA: Yes, I agree with you, Mariam, this was not a revolution in the sense that it actually changed the situation with a clear vision. This was a beginning of a process, a trajectory, that ultimately had to challenge the status quo. The status quo was not sustainable. These structures of power that keep Arab people outside politics and suppress them—challenging them was inevitable. When this inevitable moment came, the ways different people responded to it are telling, in terms of how informed these people are and what kind of analysis they have. Also it says something about the extent to which different Palestinian factions and groups are independent or not.

There shouldn’t be one person in the world who would argue against the idea of having Arab states with full representation, and people having access to power, and people living as full citizens, fully respected and with access to the political sphere and to resources, and to full physical well-being and so forth. I don’t think as a Palestinian that this will be against our interests as Palestinians. In fact, if this reality is achieved, Palestinians will be in a much better place. And to switch back to the Arab uprisings: again, we are living its implications now. These regimes have used excessive force to crush these uprisings—and are therefore perceived by the Israelis as the ultimate allies. These regimes are actually encouraging more suppression of Palestinian revolutionary potential.

We can have our criticism of the Muslim Brotherhood. But then we can go read and understand and make sense of the moment when the Arab uprising surprised each one of us and the Muslim Brotherhood was the only group that had the capacity to build on this moment and get into power in places like Egypt and Tunisia. And if we look at the last three wars of aggression on Gaza—2008-9, 2012, and 2014—the shortest one with the least human and material losses on the Palestinian side was the 2012 one, when Morsi was the president of Egypt. We disagree with a lot of the things that Morsi did and have our own criticism of him, but this was a moment when there was—for the first time—an Arab president who was democratically elected and carrying the responsibility of the revolution. This says a lot about what it meant for the majority to rule via democratic means, and for having states that represent the interests and wishes and ambitions of their citizens.

And that was the problem! These different regional actors and international players like the US, Iran, and Russia viewed and still view majority rule in our part of the world via democratic means as a threat. Of course we understand that such a moment of transition would raise the concern of different groups in these different states. But do not come and intensify these horizontal divisions inside Arab societies. Iran allies with the Shi’a in Lebanon, and the Saudis create these Sunni groups in Syria—these are both alignments of counterrevolution. The Gulf states are only one part; then there’s Israel and the US, and the Iranians and Russians—they have their differences, but these forces share one thing in common, which is preventing Arab people from getting power and having states that represent them. They understand that once we have powerful states that represent the interests and wishes of our people, then they will be challenged in a serious manner for the first time in the history of our region.

M: Yes, the powers of the world are against Arab peoples rising. The biggest problem that remains, though, is the lack of communication among activists across the Arab world. This lack of communication is so hindering. Look at us right now, sitting in this room: we have someone from Lebanon, someone from Palestine, and two Syrians. This in itself is the biggest fear of any dictator in the Arab world, because we can sit down and talk about this as the clearest problem. But then we go back out to social media, and our voice gets killed and stomped on by the leftists here talking about whether or not it’s an imperialist takeover of the Arab world, and the rightwing here talking about whether or not they should bomb us more.

MB: Honestly, I see all this coming from a disconnect with everything that happens on the ground back home, and an obsession with intellectualizing things and placing it in theory and all of that. Back home it’s such a completely different reality: there’s oppression; we don’t want to live in oppression anymore, so we’re going to fight it. But the disconnect between activists and everyone here has helped polarize the entire situation.

JA: It’s hard for people here to imagine what it means for an entire nation to rise against its own government. They’ve never experienced it. Hopefully when they get there they can teach us better models. The Arab people tried their best, and unfortunately there wasn’t an adequate analysis that was up to date with the map of class and society by 2011. That’s why it was really hard for people to predict that revolutionary moment.

Also, the left has been pretty intellectually lazy, especially when it comes to our region. The theoretical frameworks through which they read the role of imperialism, and also the relationships between different classes in different countries—I mean, I don’t really understand what kind of limited imagination one has to have in order to think that the unfolding of antagonism across social and economic strata in any given state, regardless of what rhetoric or what political positions this state has, should be put on hold.

One of the most dangerous implications of the past seven years that will affect Palestinians in the years to come was the normalization of state violence and its use to suppress the civilian population. What we witnessed over the past few years, chiefly in Syria, was an acceptance on the part of most of the international community—accompanied by disgusting justifications even by people on the left—of the slaughter and depopulation of Syria.

At the end of the day, when it comes down to people putting food on the table for their kids, I don’t think people really care about what rhetoric or what anti-imperialist position their regimes have. The “hungry masses” in Syria or Egypt or Tunisia who are unable to provide food—we’re talking about food, people who are unable to feed their kids—don’t have the luxury of time to sit down and think thoroughly about the implications of rising against these states. This is conflict, this is how history unfolds. You cannot put people’s concerns and people’s wishes and people’s ambitions on hold just because this or that regime has a “good record” or not.

I don’t know why we are still talking about this seven years after the uprising.

M: It’s as if there’s an entire side of the world that thinks we should…chill. It has become problematic. Groups used to come down to Syria and send trainers in “coexistence.” They wanted to teach us how to do the revolution. This ended up paralyzing a lot of activists, because it took people who were in this struggle—who, like you said, were worrying about hunger and day-to-day survival and could not care about anything else but the bullets that were raining on them—and it put them in a five-star hotel in Turkey and changed their reality so dramatically that they became confused.

A lot of these activists left the cause way before people started leaving the Syrian revolution, and way before it became violent, or was overwhelmed by ISIS. All of the sudden we had this change in mentality. It’s the same game the ISIS would play when they would send in a sheikh to sit down with a bunch of our activists and convince them that the whole world is against us and the best way out is to blow yourself up and go to heaven. There were people continuously sending in their people to convince our activists that the way they were doing it was wrong. Unfortunately, they succeeded.

MB: That’s what oppression is. We’re fighting a system that’s thousands of years old that doesn’t want you to be liberated, but wants you to accept the unequal power dynamics and go with it.

LM: I sense racism from this argument sometimes. Is that the right thing to call it? As if we don’t deserve to be free, or as if we don’t deserve to choose our leaders.

M: We can’t handle freedom. We’d all turn into ISIS.

LM: Exactly. There are so many arguments that say no, those people need a dictatorship to keep them safe or to keep them from creating chaos in their country.

MB: It’s the same exact thing in Palestine. You can just replace one name with another. It’s the same exact thing. This is why I’m always so incredibly shocked with people who claim to support Palestine but use the same exact arguments that Zionists use in other regions of the world. I don’t understand how they don’t see the similarities.

JA: Even these positions that we take for granted—like with many of these people with regards to Palestine—have not been the same way all along. It took so much effort and work to convert people on Palestine. At one point in time, Israel itself was a socialist country allied with the USSR, and Stalin was arming this socialist country which was fighting British imperialism. This is something that was said and believed and perpetuated. The other day I was reading a Palestinian newspaper from 1948, and there was a line that said described Tel Aviv in 1948 as “the city that dresses for every occasion,” mocking people marching in Tel Aviv with Russian outfits, carrying Soviet flags, and appealing to Stalin for support while at the same time they were expelling Palestinians. That was the narrative that Israel then furthered: that they were fighting British imperialism and its Arab allies.

If this was believed back then, it doesn’t surprised me to hear people buying what the Syrian regime is selling. But we will all judge this moment by the consequences of the actions that we are witnessing now. We are starting to witness the consequences of the slip-back of the Arab uprisings and the hampering of the Arab people from claiming their dignity, claiming their states, and claiming their rights.

And of course the Syrian people are paying the heaviest price in blood and lives—and Yemenis and Iraqis, and the Egyptian youth who are being held by the thousands in the dungeons of Sisi. But also Palestine will pay the price. In fact, Palestine has started to pay the price. Do you think that without Arab backing and support, Trump would dare to take the two actions mentioned at the beginning of this conversation? This is unprecedented arrogance. And Gaza is undergoing an unprecedented collapse. Gaza is falling apart. We can no longer talk about when Gaza will collapse. Gaza is collapsing already.

But one of the most dangerous implications of the past seven years that will affect Palestinians in the years to come was the normalization of state violence and its use to suppress the civilian population. What we witnessed over the past few years, chiefly in Syria, was an acceptance on the part of most of the international community—accompanied by disgusting justifications even by people on the left—of the slaughter of half a million people and the expulsion of millions of people: the depopulation of Syria. Millions of people were kicked out just because an imperialist country like Russia wants to keep its ally in power in Syria. That was the price.

This situation is going to encourage Israel to be more violent in its treatment of Palestinians. I am sitting and talking to you right now, but some part of my mind is absent, in another place, thinking about Gaza and the possibility of a war breaking out any time. With these dangerous precedents being set in the region, the ceiling of what states can commit against civilians has been raised to a very dangerous level. Palestinians should be worried, and this is why I always question why Palestinians are not talking about the Arab uprisings.

There is an element of denial, and an element of uncertainty, and a lack of information, and not knowing how to deal with this information. People who live in a historical moment do not look at it the same way we look back on it when it becomes history that we can read and analyze and understand from the point of view of someone who has the luxury of looking at it from a distance.

M: On that note, we leave you with part one of the Palestine episode. Thank you so much for tuning in. We will be uploading part two very soon. We hope you enjoyed it.

Thank you so much, everyone.

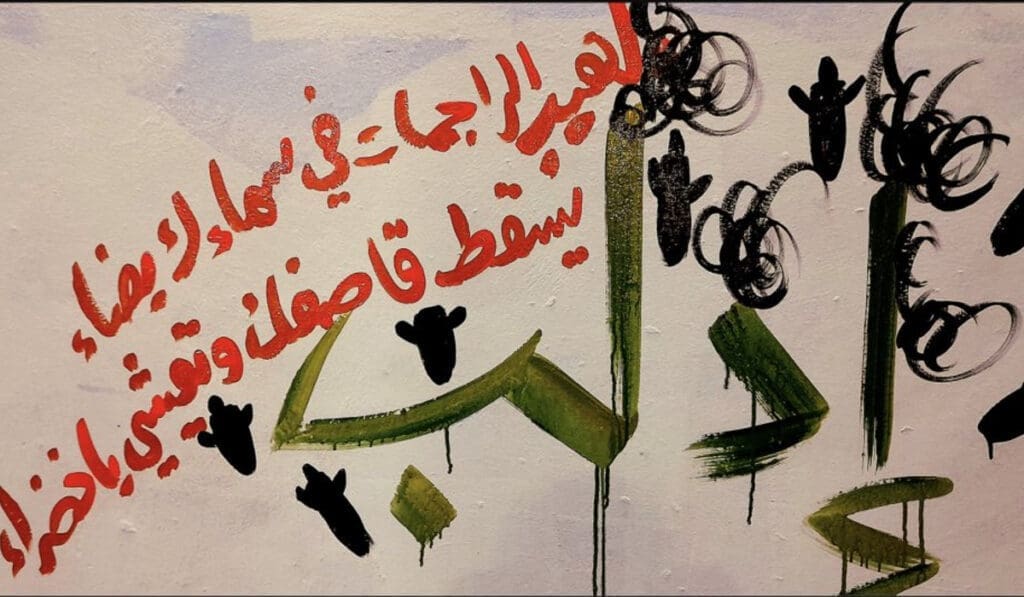

Featured image: painting of Ghassan Kanafani. All other images: paintings by Ghassan Kanafani.