Transcribed from the 14 November 2019 episode of Arab Tyrant Manual and printed with permission of the interviewee. Edited for space and readability. Audio no longer available.

If you look at the world through a framework in which the United States is this global police that has its hands in everything, and all other governments have absolutely no agency of their own—no secret intelligence of their own, no torturers of their own, no war criminals of their own, no police of their own—that just betrays a lack of understanding of individual countries’ complexities.

Ahmed Gatnash: Welcome to the Arab Tyrant Manual podcast, where we try to understand authoritarianism—and the strategies and tactics that authoritarians use—in order to better resist. I am Ahmed Gatnash of the Kawaakibi Foundation. Today I am with Joey Ayoub. Joey is a Lebanese writer who used to be the Middle East and North Africa editor for Global Voices and IFEX, and he’s doing a PhD on the politics of postwar Lebanese cinema.

Welcome, Joey.

There’s a major problem that’s causing a lot of people distress. That is, the left’s problem with authoritarianism. There’s a very widespread perception—and I definitely argue that it’s more than a perception—that the left wing, globally, has an extremely uncomfortable affinity with authoritarianism. This affinity has been a very long term problem, and it goes against some of the self-declared ideals of leftwing thought.

It’s become a bit of a joke in some circles—most people will know what I’m talking about—but what background can you give on this?

Joey Ayoub: The Canadian theorist Moishe Postone, who passed away recently, called it a dualistic worldview of the Cold War. We might call it campism. It’s pretty direct and simple in the way we can understand it. If you are somebody who calls themselves anti-imperialist, you might simplify your worldview and act upon this belief by saying that a state which opposes the state that you belong to (or that is perceived that way) is a state that you either support or at least whitewash.

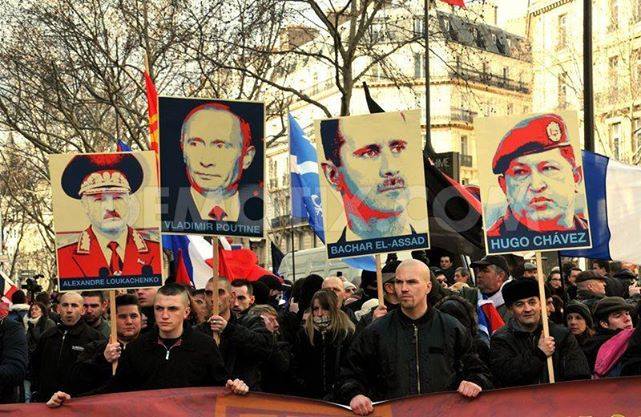

We see this most notoriously when it comes to Syria, when it comes to the Russian government. But it also comes in various formats. We could talk about the whitewashing of the Assad regime in Syria or the whitewashing of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela; or Ortega…the list goes on and on. It does get a bit messy when we get into individual countries—but there is a wider tendency. And we’re seeing this turning into a monstrosity because of social media—or at least social media is making it more apparent; I don’t think social media is necessarily creating it.

This is a very old phenomenon. People on the left who are anti-authoritarian, like myself, have the term tankie. We use it sometimes as an insult, to accuse other leftists of being authoritarians. But it has very dark origins. Tankie comes from “tank.” It goes back to 1956 when the Soviet Union invaded Hungary with tanks. That split Communist parties, in the UK especially, into what we might call today tankies and anti-tankies—those who would justify the invasion and those who would not: those who were opposing it. We saw this again later with the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the invasion of Afghanistan, in ’68 and ’79, respectively.

The term sort of died out in the nineties and the early 2000s, but it’s coming back again now because we’re seeing this rhetoric of “anti-imperialism” being used to justify all sorts of horrible regimes.

AG: So basically there’s this binary mindset which splits the world into imperialists and anti-imperialists, and anybody who we perceive as being on the anti-imperialist side is on our side, is our hero, our guy, and we support them, and if it seems like they’re doing some uncomfortable stuff we try to minimize that, we try to justify it, we try to ignore it.

I guess there are two types. Some of them are widely admired and have very positive principles (which is what makes it uncomfortable when you realize that they’re engaged in whitewashing for certain brutal regimes) while others have a more generalized condition where they just seem to bounce from country to country legitimizing every authoritarian they come across, from Latin America to the Middle East to China. It becomes a hatred of “the West,” a reverse us-and-them, and anybody who is fighting America is a good guy.

In that way it’s a form of radicalization. Rather than Hindutva, which splits the Hindus from the Other; or Islamic extremism, which has the believers and the unbelievers; we end up with imperialists and anti-imperialists, or even capitalists and anti-capitalists.

JA: The worst thing you can be called by these people is a “liberal.” That’s how they insult you. They think that’s the worst thing they can call you—which is a bit ironic, I think.

But the government in question doesn’t have to actually oppose your government, as long as it does so rhetorically. Russia doesn’t necessarily oppose the US government in Syria. The actual dynamics are much more complicated than this. They bombed together in ISIS territories, and they shared the sky. That now-notorious attack, the missiles that Trump launched last year—before doing that, they announced it to the Russian government, to avoid accidental fire.

The details can be quite incredible. We can talk about Nicolás Maduro sending $500,000 to Trump’s inauguration. We can talk about Ortega: one of Trump’s religious preachers was invited by Ortega to blend social conservatism with “anti-imperialist” rhetoric. Obviously the most notorious example is Vladimir Putin, one of the most rightwing politicians in the world today, also blending anti-imperialist rhetoric with ultra-rightwing social conservatism.

The facts in themselves don’t matter. It doesn’t matter whether the government in question is actually “opposing” the US or not.

AG: A lot of the time anti-imperialist rhetoric is deployed to disguise a ruler’s own imperialist designs, whether it’s Vladimir Putin annexing parts of Ukraine and taking over Syrian territory, or whether it’s the Chinese government and what they’re doing to minorities in the far west—not to mention their economic activity elsewhere, like in Africa. Even Gaddafi, the lauded anti-imperialist hero, also tried an imperialist venture at one point, and he was so humiliatingly defeated in the war in Chad that he never had the courage to try it again. None of these people are for self-determination in any way.

JA: Absolutely not. We can speak about Gaddafi’s love for Berlusconi, too, and that doesn’t exactly portray him as someone on the left. But again, it really goes back to the fact that this has nothing to do with reality.

I hesitate to describe it as specifically Western or not Western, though that is how I used to look at it. There are examples that I have learned since. It is very much a problem of the old Arab left, too. By “old Arab left” I mean the one that was not crushed by the regimes, the left that was tolerated by the regime, like the old left in Syria (whatever is left of it, anyway).

AG: That is also a tragic example. There are certain Arab leftists, mostly of the previous generation, who spent many years advocating for the rights of Palestinians, writing about the oppression that impoverished people face in the Arab world, and then they come out and defend Bashar al-Assad, and even support Hezbollah while they’re shelling Syrian children and murdering innocent civilians. And the reason is because Assad is ostensibly pro-Palestine—even while he’s murdered over four thousand Palestinians, including in torture camps.

JA: Hezbollah—we can speak about this example briefly since I am from Lebanon—is in an open alliance with the most anti-Palestinian party in modern Lebanese politics, the so-called Free Patriotic Movement, led by Michel Aoun, the current president.

AG: And Aoun is a war criminal himself.

JA: Yes. Again, it goes back to this point. See what I mean? It is a worldview predicated upon a sort of hostility towards reality. It’s almost like the whole point of it is an unwillingness to accept complexity, to accept nuance, to accept the possibility that in one situation there may be more than one oppressor. One may be opposed to US intervention in Syria, but one should at least recognize that the US is not the most important actor in Syria—and also, that this is not abnormal.

If you look at the world through a framework in which the United States is this global police that has its hands in everything, and all of these governments have absolutely no agency of their own—no secret intelligence of their own, no torturers of their own, no war criminals of their own, no police of their own—that just betrays a lack of understanding of individual countries’ complexities.

AG: And a desire to reduce every country to a single template, which is: native people doing their best to resist CIA plots and American imperialism, and being destabilized from within. Whenever there’s a native movement against a tyrant, it’s a CIA-funded plot; it’s US-funded, it’s US-backed agitators. They’re smearing protesters in Hong Kong right now, and they’ve been smearing Bolivian environmental activists raising the alarm about massive government-supported (or certainly government-ignored) forest fires burning down parts of the Amazon.

We mentioned Palestine—there’s this phrase “Progressive except Palestine.” Here we get the opposite: only progressive on Palestine. A lot of people are extremely passionate about the rights of Palestinians, which of course we support—but it’s jarring that just across the border in Syria, a few kilometers away, in a country which hosts its own refugee camps of Palestinians: as soon as they cross that border they flip 180 degrees.

There’s this really bizarre example I saw in a tweet earlier. I’m not going to name this guy, but he tweeted from Damascus—on some kind of apparently state-sponsored whitewashing trip—about the bars, and how cohabitation was becoming more accepted after people had seen the “radical extremist” rebels, and how people were able to drink at night…and an Israeli friend replied pointing out that there’s another country in the region which touts the ability to drink alcohol there, and go to bars, and their tolerance of LGBT people…and they’re equally repressive on human rights, but you’re not whitewashing them.

The problem with the way the Palestinian cause is typically framed is that it’s seen as the only cause. But the post-2011 landscape has de-centered the Palestinian cause in the minds of many Arabs. “De-centered” does not mean it is not important. Absolutely not. It just means that those among us who want to be more progressive about it are trying to link it to other struggles, in the Arab-majority world and beyond.

JA: This has been pointed out time and time again for years now, including by Palestinians. But the difficulty in speaking about the Palestinian cause is that there is the Palestinian cause, as in: the rights of Palestinians to self-determination and so on—but then there is The Palestinian Cause™ that is dominated by Westerners, especially online (it’s not just Westerners, it’s just being dominated by Westerners; there are many Arabs who participate in this as well). The problem is that it goes back to this binary. It says that Israel is a state that is unlike any other state in the world, as opposed to saying that Israel is a state that commits horrific violations of human rights and we should oppose it because of that, and we should deconstruct how it was founded, we should deconstruct nationalism, we should deconstruct Zionism, we should deconstruct settler-colonialism—and we should go further and understand the history of the region, the history of the Holocaust, the history of so many different things—but that requires an acceptance of complexity.

The problem with the way the Palestinian cause is typically framed is that it’s seen as the only cause. But the post-2011 landscape has de-centered the Palestinian cause in the minds of many Arabs. I should be very careful here, because “de-centered” does not mean it is not important. Absolutely not. It just means that those among us who want to be more progressive about it are trying to link it to struggles throughout the region, in the Arab-majority world and beyond.

AG: And there’s a recognition by many people that Palestine has been used as an opiate for so long by dictators who are willing to use it as a fig leaf for their repression: “Oh, well, at least Gaddafi is pro-Palestine.” Other regional rulers, and even Latin American rulers, whenever they’re faced with something inconvenient, will make some kind of overtly pro-Palestinian gesture as a distraction.

JA: And those of us who are especially familiar with Syria obviously know that one of the most notorious branches of the Assad regime’s secret police is called the “Palestine” branch.

What I try to do sometimes is take what some leftists say and see if there is a similar or identical quote by someone on the far right. There are cases that are very interesting. By and large, people on the left who engage in these tendencies (to put it kindly) are in denial about their fellow travelers. One person that I tend to focus on is a man called Matthew Heimbach. He’s one of the leaders of the white nationalist movement in America. His group is the Traditionalist Workers Party. In 2014, he said, “We must understand a unity between those who struggle against the Zionist state and international Jewry here in the West, and those on the streets of Gaza, Syria, and Lebanon.” This was not just any month in 2014; this was during the war on Gaza by the Israeli state. He continues: “We are facing a truly satanic enemy, one that cannot be understood except through the lens of Christianity and Christian prophecy.”

I mention this guy not to say that leftists are thinking like him—obviously not. This guy is quite an extreme case on his own. I’m just trying to point out that if someone calls themselves anti-Zionist or anti-imperialist or whatever sounds like a good position to have, that doesn’t automatically mean they have good politics. This feels like it should be more obvious, but unfortunately, as we’ve seen time and time again, it doesn’t seem to be as obvious as it should be. Heimbach says he’s opposed to the Zionist state. Well, I am opposed to the Zionist state. But then he says he is opposed to “international Jewry,” and for me that is a big red alarm; that is obviously antisemitism. This guy is a Holocaust denier, pro-Nazi, etcetera.

What’s fascinating about Heimbach is he’s this white guy from America who happily posts photos of himself with Hezbollah t-shirts and SSNP flags. This symbolizes that just as now we have these leftists, as you mentioned, who are visiting Damascus on a tour and posting about it on social media—just a few days ago there was the far right from France that did the same thing, and the far right from Italy, Casa Pound, did the same thing before that. I’ve been following the visits to Damascus, especially by Westerners, and it’s been something in the ballpark of seventy to eighty percent from the far right, and something like twenty or thirty percent from the so-called left. There is Tulsi Gabbard, there is Dennis Kucinich, there are some people on the Spanish left who I focused on a couple years ago. And it shows that there is a severe cognitive dissonance among people on the left who still want to pretend like they don’t see the writing on the wall as to what this actually means, and especially what this means to Syrian refugees who have fled this regime.

AG: I’m personally very fond of horseshoe theory. In the first couple years after the Arab Spring began, I remember Nick Griffin, the founder of the British National Party, one of the most notoriously racist figures in modern British political history, was in Syria to congratulate Assad and support him and lend him is solidarity. And like you said, as various European far-right, nationalist, and even fascist figures are continuously visiting, self-proclaimed leftists are there as well.

JA: We can think about the BNP on one side, and then there is also someone like George Galloway, who is openly pro-Assad, hugging someone like Nigel Farage. It’s become much more open in the past few years.

I remember very well: in 2015 and 2016, especially in the final months before the fall of Aleppo at the end of 2016, myself and few Syrian and Palestinian and other friends were having a conversation, and we agreed that these people who have been causing so much damage—by which I mean these people who are engaging in disinformation online, whether consciously or unconsciously—will at some point lose. It’s not that we are worried that they will create a whole system of their own in ten years. Our fear (and it was vindicated by the end of 2016 and, I would say, even to this day) was rather that they will take up so much space online that most of the time the rest of us (activists, humanitarians, refugees, all of these people who just oppose atrocities) are basically on the defensive. We have to spend so much time just debunking campaigns of disinformation.

But to go back briefly to horseshoe theory: it’s not that I disagree with it in practice; this does seem to be the case time and time again, and I have no intention of denying it. My only addition is that I think the words far left in themselves don’t mean anything. I think the words far right are very obvious, and very distinctive. It is associated with neo-Nazis, white nationalists, the KKK; and in the Arab version, something like the SSNP or the Assad regime, Ba’athists (Ba’athism is basically a syncretic form of nationalism and so-called Arab socialism, which ended up just being authoritarian, one-party state rule).

These people who have been causing so much damage, who are engaging in disinformation online, whether consciously or unconsciously, will at some point lose. Our fear is that they will take up so much space online in the meantime that the rest of us are always on the defensive. We have to spend so much time just debunking campaigns of disinformation.

AG: We mentioned George Galloway. I remember him being extremely big in UK politics. He was very vociferously against the Iraq war—one of the few political figures who was that vocally against it. And he was vindicated, of course. He was also very strongly pro-Palestine throughout his entire time in politics—and many people remember that time, when it was incredibly difficult to get a mainstream political figure to talk about Palestine. Many people (especially those who have links to the Middle East) remember very fondly his advocacy against the war.

I’m mainly talking about the older generation here: they have a sentimental bond to some of these figures who have since turned extremely reactionary. You mentioned that over the Brexit vote, Galloway actually embraced Nigel Farage. He’s embraced Bashar al-Assad, the butcher of Syria. He’s vociferously defended Gaddafi. He actually engaged in defense of Saddam Hussein as well, back in the day.

There are other even more respected figures on the left, like Noam Chomsky, the celebrated intellectual, who has made important contributions. But it came as a very uncomfortable discovery to me when I found out, post-2011, from Syrian friends, about his regressive stances on Syria. People told me that he’d actually had a history of genocide denial in other parts of the world as well.

JA: Yes, Bosnia and Cambodia most notoriously. Chomsky is also a very interesting story. I actually met him when he came to Beirut in 2013. I was graduating from the American University of Beirut as an undergrad, and he was the keynote speaker. We met briefly after that. He was a very formative influence in my early years, pretty much up until roughly 2013-14. 2013 is when I started really getting into Syrian politics. And I had absolutely no idea about anything related to Bosnia, or anything related to Cambodia.

But I want to say two things at the same time, and I will link it to what I want to say about George Galloway as well. You mentioned that he whitewashed Saddam Hussein—and he did, absolutely. And this was the trap. This is something that we can say now, in hindsight: there’s a good argument to be made that during the build-up to the war on Iraq, Iraqi voices were not privileged. This was an early warning sign (but only something I can say in retrospect, as someone who was twelve or thirteen back then, so I didn’t know anything about it).

Galloway’s whitewashing of Saddam Hussein should link the story to another one: you mention that he is pro-Palestine; I would nuance it a bit. He’s not necessarily pro-Palestine, he is anti-Israel. I know that most of the time, these are pretty much the same thing. And if you are a Palestinian, it is not my position to say yes or no: if you think those are the same thing, okay. That is a politics that needs to be resolved locally. But non-Palestinians don’t get that privilege, in my opinion; they shouldn’t get that right. If they support Palestine because they oppose Israel, okay, that’s one thing. But we need to demand: how serious is their support of Palestinians? George Galloway only supports Palestinians in Syria as long as they are pro-Assad. If they are not pro-Assad, these Palestinians are not worthy of his support.

For me, this creates a hierarchy between worthy human beings and unworthy human beings, and I think that’s extremely dangerous. It’s selective empathy, selective solidarity.

AG: Two things caught my attention there. One of them was that Iraqi voices weren’t really elevated during the opposition to the Iraq war, and that was a warning sign. Since then we’ve seen leftwing movements in the UK rallying against a fictional “war on Syria” not only ignoring Syrian voices but actually making an effort to eject them and silence them and remove them from view when they say the uncomfortable, which is: “You guys are standing in solidarity with a dictator who is butchering my country.” And they have become more and more regressive over time.

JA: You’re obviously referring to the Stop the War movement in the UK. I wrote an article about them back then. There was something fascinating that happened; I think you will especially identify with it because you’re Libyan. Chris Nineham, who’s a co-founder and deputy chair of Stop the War, wrote an article basically opposing a no-fly zone—which was barely being promoted in any serious terms in British politics, but as usual they were overblowing it. The argument was along the lines of, “You support a no-fly zone? Ask Libyans about it.” And while he’s asking us to ask Libyans, there isn’t a single Libyan quoted throughout. Not a single poll, not a single activist, nothing.

Now in retrospect—it’s kind of like I started realizing things in reverse. Syria was a retroactive warning sign. Ramah Kudaimi, a Syrian-American activist, put it this way: “Palestine separates liberals from radicals, and then Syria helps us figure out which radicals [are] out for real liberation and which [are] just ideologues.”

That’s the problem with hindsight, though: you wish you had that back then. There were early warning signs. And I’m sure Bosnians would say the early warning signs were not in the 2000s; the early warning signs were in the nineties. And there are people who will say they were in the eighties, and, no, they were in the seventies, or no, they were when the tanks went in to Budapest.

It will always be extremely difficult to say when this started. There are many people among the anarchist tendencies (I tend to be in that category) who say no, it started one hundred years ago. Even before then. It started with the Second International. It’s extremely difficult to say when it started.

I think when it comes to the post-2011 era, though, the thing we should at least be saying is that it requires a new framework that encompasses all of these nuances and learns from all of the mistakes that were committed prior to 2011, and of course since 2011.

AG: We can’t say right now without an exhaustive study when it started, but we can certainly say that social media and the modern media landscape has made it undeniable now. And those of us who may have missed warning signs earlier can only apologize to those we didn’t listen to at the time—apologize to Bosnians who were pointing this out, and say we’re sorry we didn’t listen.

JA: That’s exactly it. We should be very aware of the fact that back when Bosnians were being slaughtered, and even before the genocide was happening, in the months before the multiple genocides, the warning signs were already there. There were journalists there. Not just Bosnians, but Western journalists were there, who were saying that this is what’s happening. They were literally documenting it as it was happening. This was before the time of the internet, obviously. And it says something that even back then many of those who did speak out against what was happening were not necessarily people on the left. That’s a sad legacy of that time.

AG: It’s just a reminder that people’s political orientations are far more complex than a simple left-right binary, and to deal with these critical problems across the world we need to work in coalitions and reject purity politics and narrow-minded tribalism by political sect.

JA: That’s especially true when we speak about wider-angle global politics. On the local level it can be very difficult—I don’t want to feel like I’m jumping from one country to another aimlessly—but especially when it comes to global politics, there are already principles in place that need to be acknowledged.

For someone who was opposed to the no-fly zone in Libya, for example—my position towards that person is that if you want to be opposed to that particular policy, given that you are not the one who would suffer the consequences, you also need to work on proposing an alternative. And if you don’t have an alternative, you need to be humble enough to say so. You might say, “This bothers me, but I admit I don’t know what to do in this situation.” Instead, what we have been seeing are people giving themselves the authority, self-appointing a right to dictate what other people should or shouldn’t want. That’s what I find extremely problematic.

The failure of that movement, the largest antiwar protests in UK history as far as I know—there was so much momentum that crashed when it lost. When that momentum didn’t lead to something that we wanted, which was to stop the war, then it morphed into something else.

AG: Even beyond that there are people who go so far as to smear people who do support an intervention, and call them CIA stooges or pro-imperialists or whatever. I deeply respect the people who opposed intervention in Syria, even while I passionately disagreed with them. And likewise with Libya, I still remember and respect the people who opposed it but with humility at the time, and said, “This is a horrific situation, and I sincerely think that military intervention will make it worse for these reasons; I’m willing to have a debate but I don’t think this is the right path,” rather than saying “You guys are all pro-NATO.”

But I want to go back to one other thing you mentioned while you were talking about Galloway, which is that he isn’t pro-Palestine as much as he’s anti-Israel, and you mentioned some stuff about antisemitism. This is something else that we’ve seen come out of the left in recent years. There have been scandals in the UK, political scandals involving large numbers of antisemites in the Labour party. I think most people who have been in those kinds of circles, not just in the UK but internationally, would agree that there is a problem and that it has been tolerated or quietly ignored for way too long. Even if you disagree on the extent of the problem and whether the media has tried to have a ball with it, there is a very uncomfortable accommodation with antisemites in the “pro-Palestine” cause.

JA: The media did have a go at it, but that doesn’t deny the underlying problem.

Not everyone who is an anti-Zionist is an antisemite. That is very obvious. That should be repeated, especially as there are pro-Netanyahu people in the Tory party or lobbyists and politicians in the Republican Party and even in the Democratic Party in the US who use that on purpose to silence anti-Zionist voices. At the same time, that does not mean that no one who is an anti-Zionist is an antisemite. You can be an anti-Zionist and an antisemite. You can even be an antisemite and pro-Zionist. Viktor Orbán is one notorious example. Netanyahu’s own son, who is obviously Jewish, peddles antisemitic conspiracy theories when it comes to George Soros.

These things are complicated, and they have to be recognized as complicated. But just as the Israeli government cynically instrumentalizes antisemitism and the memory of the Holocaust for its own purposes—very nefarious purposes that actually make the problem much worse—that doesn’t change the fact that I cannot control what the Israeli says and does. I can only oppose it and campaign against it. What I can do is make sure to say that not a single racist, antisemite, homophobe, Islamophobe, xenophobe, misogynist, transphobe—all categories of hate—not a single one of them can be tolerated or accepted in our spaces. That is something I can do as someone who is a pro-Palestine activist. That is something that is in my power.

AG: I really like Iyad [El-Baghdadi]’s position on this, which is extremely uncompromising. I remember him tweeting: “This Palestinian will block with extreme prejudice anyone who sends [me] antisemitic messages, especially if under the guise of solidarity with Palestinians.”

JA: Unfortunately it’s not as uncommon as most of us would want. This is something that needs to be dealt with. Americans, by and large, and I should say this to their credit, are doing a much, much better job than European are, and a way better job than Arabs are, when it comes to differentiating between the two. That goes back to the specificity of Jewish-American progressive politics in America and how they are much more willing to be intersectional than other groups of people in the world.

AG: Ultimately what this whole saga shows is that anti-authoritarianism and progressive activism can’t work without intersectionality. You can’t focus on a single cause to the exclusion of all else, because you cannot have functional coalitions with people who are willfully complicit in other types of oppression, whether that’s pro-Palestine activism in league with antisemites, or pro-Arab Spring activism in league with people who have denied genocides in other places, or otherwise.

To go back to the narrative we were tracing of the left in the West: basically, 2011 broke the left, and that was arguably a function of the Iraq war. It was so destructive and so horrific and so unnecessary, and the process that led to it so flawed, that something in the Western leftist psyche has been unable to move on from that. And when 2011 happened, the first and the only comparison they were able to make was 2003 Iraq. And every time an intervention is urged to stop imminent bloodshed, every time support is urged for civil society fighting an authoritarian, the comparisons are immediately to Iraq, and “this is Iraq all over again,” this is another intervention, this is another war.

JA: What happened in 2003 was that people opposed this obviously illegal and immoral and barbaric invasion by the United States and the UK and their allies—but then, by and large, they stopped thinking about Iraq. You might say they continued thinking until Saddam’s execution, maybe, since that was in the media and everything. But at some point later on, what we might call the civil war and the collapse of the state, and the increase in sectarianism under Maliki, and all of that—it seems to me (again, this is something I can only say in hindsight, because I was still too young back then to really understand this fully) that they distanced themselves from Iraq.

And I don’t call this the “shock” of the Iraq war. That would take away from the people who were actually shocked by the Iraq war, who were the Iraqis. They were the primary victims of that. But the failure of that movement, the largest antiwar protests in UK history as far as I know—there was so much momentum that crashed when it lost. When that momentum didn’t lead to something that we wanted, which was to stop the war, then it morphed into something else by mostly ignoring what was happening in Iraq after the invasion.

Then I think the financial crash created a different monster. When it comes to the Western left’s understanding of the world (to paint with very broad strokes), these dual shocks disoriented everything. If you remember, in the early days of 2011 there was lots of support for the Arab Spring. This I can remember. I was twenty. I remember very clearly that there were columnists and journalists and activists and others saying things like “The Occupy Movement must send their solidarity to the Egyptians and the Tunisians and the Libyans and the Yemenis.” But then, when in 2011 and 2012 Syria started taking a different path (not that the others were necessarily much better), a much more vicious and destructive one (and so quickly!), it upended another expectation of what the Arab Spring was “supposed” to deliver.

This goes back to an unwillingness to accept complexity. There was no real reason to believe that 2011 would necessarily end up with amazing results. We could have hope that this would be the case, and we could work towards it, absolutely. But nothing is written in stone.

And the Assad regime—Bashar al-Assad inherited his throne from Hafez al-Assad. Hafez al-Assad, as most Arabs know (and I hope many other people would know), committed one of the most brutal massacres in the city of Hama in 1982. That silenced three decades worth of generations of Syrians. That’s why in the early days of 2011 many Syrians were opposing Syrian activists on the street—especially those of the previous generation, because the youth was especially dominating the streets at the time—by telling them, “you will be massacred as we were in 1982. The same thing will happen to you in Homs as happened in Hama.” Unfortunately, Homs actually did suffer quite a lot. Aleppo also did. Daraya as well. Dera’a as well. And now we’re seeing it in Idlib.

We should act as though we are one whole: the Gaia hypothesis of the planet. We are one species. As cheesy as that sounds, we all go through experiences and we need to understand that people go through experiences that may be different from ours.

I know I went from the Western left here to Syria. But what I’m trying to say with all of this is that there is a certain resistance—not in the good sense of the word—to reality. I don’t want to say it’s just one factor. But this goes back to the concept of liquid modernity that Zygmunt Bauman coined some years ago, and its associated term liquid fear. It helps us understand (only helps, I should emphasize. It doesn’t explain everything. Racism has always been there too, for example) why refugees arriving in Europe created this hostile reaction; why the left is so confused and feels so lost about anything that isn’t local. They can focus on racial justice at home, reforming the prison system, education, etcetera, but as soon as it comes to international solidarity, to thinking as individuals standing in solidarity with other people, it’s almost like they need permission from these thought leaders on the left before knowing how they should or shouldn’t act.

AG: I guess we have to mention that racism is an aspect of it, because there are large segments on the left who just refuse to ascribe agency to brown people in other parts of the world, in the global South. When brown people revolt, it’s because the CIA told them to, it’s not because they have deeply-held grievances and they’re capable of their own mobilizing and their own organizing. It’s part of Western plots. And when native activists advocate for solutions for their countries, for support, they are often shut down, silenced, ignored, and even given a condescending kind of “You don’t know what’s best for you, you don’t understand what’s going on.”

JA: Just in the past few months, we’ve had this with Venezuelans, with Nicaraguans, and with people from Hong Kong. We’ve had prominent activists from all of these places trying to be as nuanced as they can in these situations—which can be very difficult if you are literally under attack! We have to be humble enough to see how difficult it must be in their situation to be nuanced. I should say this honestly: I wouldn’t judge someone from Venezuela who supports intervention against Maduro. I wouldn’t judge that person because I am not in that person’s shoes. I would still oppose that position because of my wariness of what that might do. But that’s different.

Hong Kongers were being beaten on the streets by Chinese police—and they were so organized, to the point that Western leftists and activists throughout the world should be learning from how Hong Kongers have been organizing, because some of the things they’ve been doing are simply extraordinary. Instead, while we do have some solidarity here and there (to the credit of the Democratic Socialists of America, they did stand in solidarity with the people in Hong Kong), even among those who rhetorically stand in solidarity there seems to be a sort of hesitation that wouldn’t exist if the picture were clearer, like, for instance, when Israel attacks Palestinians. That seems much clearer. We know who’s the good guy, and we know who’s the bad guy, so we stand with the good guys against the bad guys. But for some reason when it comes to Hong Kong and China, well, we don’t know much about it. That’s fine, no one knows everything. But let’s take some time and learn from the activists on the ground, from the writers on the ground, from the academics on the ground. People in Hong Kong have access to the internet, unlike people in mainland China, and they are more than capable of telling us what’s happening.

Instead of doing that, we look among those who look like us—Western leftists do, I should say—and we wait and see what they are saying. What is the conversation? How is the conversation happening on Facebook and Twitter? Who is dominating the retweets and shares? It’s almost like we form our opinion by taking a bit of this, a bit of that, and going with the flow, instead of having principles that we then apply regardless of who the oppressors and the oppressed are.

AG: You’ve mentioned one possible solution to this crisis on the left: centering native voices and listening to people on the ground who are dealing with the issue, and taking the time to understand what they are saying—ask them, platform them, and have them give the solutions to their context rather than applying poorly-understood lessons from elsewhere, and poorly-fitting templates. What other solutions are there to this?

JA: In addition to what you just mentioned, the basic principle should be that we stand in solidarity with people, not states. That should be very, very clearly delineated. It doesn’t mean that if people express themselves democratically in a way that manifests in a state format that we should ignore them. I’m not saying that. I’m saying that the priority should be to stand in solidarity with people, not states.

If we speak about Brazil, we might say a majority of Brazilians—or at least those eligible to vote—voted for Bolsonaro. Doesn’t that mean we should support what he is doing? Obviously for me the answer is no. There are those who did not vote for this guy who are suffering the consequences of those who did. I’m thinking especially of the native peoples of the Amazon. For me, as someone who would always prioritize, as much as I can, people over states, it’s a no-brainer. The extension of Brazil’s colonial policies to this day has barely changed when it comes to their rights. They are suffering in a way that is going to hurt us all—and that’s the point of this whole concept, that we should all act as though we are one whole: the Gaia hypothesis of the planet.

We are one species. As cheesy as that sounds, we all go through experiences and we need to understand that people go through experiences that may be different from ours. I’m reducing it to an individual level, because—especially as social media blurs the space between one continent and another, one time zone and another, even blurs the historical obstacle when it comes to languages (now that we have translations on Facebook and Twitter and Google and that sort of thing)—there is this potential to create a network based on basic principles that most people, when polled in a non-partisan way, basically say they believe in: they believe that the world should be fair. There should be some justice. There should be some kindness. And there should be some sort of functioning system that benefits most people instead of benefiting just a minority (here I’m talking economically especially, but also racially, and in terms of gender, etcetera).

AG: I was going to point out the diversity of Western movements, especially the inclusion of women and people of color and other minorities—with the important caveat that this in itself is not a solution, because there is plenty of representation for women, people of color, and minorities among genocide deniers and tankies.

JA: We need to accept that the way things have been done so far is simply not working. It is a broken way, a broken framework of viewing the world. The capitalist framework of viewing the world wasn’t just outdated in the nineties. It was outdated in the forties and fifties. It was outdated as soon as the Second World War finished. We are still resisting the lessons of the decades that have passed, and it is a bit terrifying, because we are entering a new phase in human history that has to do with things like the role of AI, the role of deepfake videos, the fact that bots are becoming increasingly convincingly human (to the point where you’re not always entirely sure whether the person you’re communicating with is really a person or not). And that, in the hands of authoritarian governments—even in the hands of democratic governments—is something that we should be concerned about.

If we’re still spending most of our time repeating basic principles that by now should be taken for granted, we are essentially borrowing future generations’ time. We are stealing from their time. They will have to suffer the consequences of our failures in the same way that we are suffering the consequences of previous generations’ failures—as well as learning their lessons. I think that future generations will definitely learn from us, but we should at least, as much as we can, make it easier for them and not impossibly difficult (which is what we’re doing now).

AG: We have deepfake videos already on the way, and people already have no problem denying reality even without disinformation that convincing.

But anyway. This has been a really insightful conversation, and I look forward to continuing it in the future. My solidarity goes out to people on the left wing of politics worldwide who are working against these authoritarian trends. I think your work is extremely essential for our future.

Thanks, Joey.

JA: Thank you very much, Ahmed.

Featured image: composite image of an early regime airstrike in Syria—an okay thing by current “antiwar” standards. Source: MG the OG.