Transcribed from the 20 July 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole episode:

What we have learned from the Portuguese revolution is that people can change. They can change from being afraid, from being a coward, to being brave and not being afraid anymore. They can change from being individualistic to learning how to cooperate in freedom.

Chuck Mertz: The Portuguese revolution of 1974 not only toppled a dictatorship but it ushered in a new way for the Portuguese to engage with politics, leading to beautiful explosions of direct democracy throughout the country.

Here to tell us what can be learned from the Portuguese revolution, by would-be revolutionaries today, labor historian Raquel Varela is author of A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution. Raquel is professor at New University of Lisbon and senior visiting professor at the Fluminense Federal University. She is president of the international association of strikes and social conflicts, and co-editor of its journal.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Raquel.

Raquel Varela: Hello, thank you for the invitation.

CM: You write, “For those who want to overthrow the system that oppresses them, it helps to learn and remember and be inspired by others who have tried to do the same.”

So I want to get a feeling for what this revolution was about. What caused this revolution? Over the last few years, we’ve had guest after guest tell us to learn and be inspired by those who have succeeded before us; we should look at those who have been the most resilient—and those are the most marginalized. In other words, as a recent guest told us here on the show, “We’ll all be free in the United States when black transgender disabled people are finally free. So look to the most marginalized for their success in standing up to power. Look to the most oppressed.”

How oppressed were the people of Portugal that led them to overthrowing the dictatorship?

RV: This was certainly the most radical revolution after the Second World War in Europe. Although Portugal was a backward country, a semi-peripheral country, it was a European country. The US was extremely worried about Portugal, and about what Gerald Ford called at the time the “Red Mediterranean.”

There were anti-colonial revolutions that started in 1961 in the former Portuguese empire, and these struggles led the new ranking officers of the army to do a coup d’etat in Lisbon, on 25 April 1974. But this coup d’etat opened the door to the most radical process in Europe and one of the most important revolutions of the twentieth century. I say this because one-third of the Portuguese people were involved in dual power organizations: workers’ commissions, neighborhood commissions, soldiers’ commissions. This is three million people, out of ten million. They were involved in protests, strikes, and dual power organizations—organizations against the state that they built from the rank-and-file of the welfare state—for the right to job security and labor rights.

Let’s say that the vanguard, to use a typical concept, was really the industrial working class of the three main cities, but this was together with middle sectors: physicians, teachers, nurses. This is a late revolution, in the seventies. The service society was already fully built. And these sectors stood together with the traditional industrial working class to make a new country.

And this really is a new country. I have to remind our listeners that Portugal was an extremely poor country. It had the longest-standing dictatorship in Europe at the time, forty-eight years, and was an extremely poor country. Even in Lisbon, 100,000 people were living in shantytowns in 1974, with no access to water. Just one quarter of the Portuguese population had access to clean water at the time, to give an example of how backward it was.

But it is uneven, because this was a European country where, during the sixties, international capital flew in looking for valuation and revaluation of capital. Here in Portugal there was cheap labor, working within a modern subcontract system where multinationals from the US, France, Belgium, Germany, and elsewhere were operating. In the meantime we still had people in the countryside living in the middle ages, in the south where they demanded deep land reform. And they were together. There is a rule in Portugal that people who work with their hands stand together.

So on 25 April, in almost every company in the country—and hospital and school—a little soviet was born. Not because people were socialists at the beginning or had a socialist consciousness; they might never have heard the word socialism before. But they went to their jobs and asked, what shall we do? Well, first of all we have to say no to the colonial war. One million young men had been mobilized over thirteen years to the colonial war against the African people. So the first thing they did on 25 April, in almost every company, and certainly every company in the next two weeks, was to say no to the colonial war and demand democratic, free elections.

But immediately, this is how a democratic revolution turns into a social revolution. They asked, well, who are we? We are workers. So what do we want? We want an eight-hour workday, we want equal pay for equal jobs (women were very strong during the Portuguese revolution, because as male workers went to war, there was a huge feminization of the labor force), we want a welfare state, we want a free universal health system, we want universal education through university for everyone. We want Saturday and Sunday to rest. We want paid holidays.

This was an incredible process. The most backwards people—sometimes we have to say, most subjectively, they were cowards for forty-eight years—became brave and encouraged and took part in a process of change. This is what I want to analyze. What we have learned from the Portuguese revolution is that people can change. They can change from being afraid, from being a coward, to being brave and not being afraid anymore. They can change from being individualistic to learning how to cooperate in freedom. They can change from being just dedicated to work and family, to suddenly dedicating themselves to the community, and taking part in the political and public sectors.

Politics was no longer something for specialists. Thirty percent of the Portuguese people could not read properly or could not read at all at the time, and these people went to the neighborhood commission, and said how the houses should be, why we should occupy a place to be a kindergarten, how the children should be taken care of. They did this together with physicians that didn’t have access to the public system, and occupied buildings that nowadays are part of the public health system. In the Portuguese revolution, we see the best of people coming out. We see that people can change and really make a different world.

We have to look at how these people organized, how they got from a society where politics was forbidden, unions were forbidden, parties were forbidden, to a process where they were organized every day, debating every day about what society they wanted to live in. They built wonderful things.

Today this is a huge lesson. Because the bourgeoisie—or the ruling classes or the corporations and the state—cannot solve things, cannot make a decent society for the majority of the people. This is why I feel it is so bad not to remember this process in Portugal, because it was a process very rarely seen in history, from which we can learn a lot. In comparison to Chile in 1973, the Portuguese revolution was a semi-victory. In order to stop a revolution where workers take power, the Portuguese bourgeoisie had to call the reformist parties and build what they had in France after the Second World War: a welfare state, social security, and jobs, and they had to nationalize the banks and the big companies, and do land reform.

They were obliged to do reforms in this revolution. So we have to look at how these people behaved, how they organized, how they came from a society where politics was forbidden, unions were forbidden, parties were forbidden, to a process where they were organized every day, debating every day about what society they wanted to live in. They built wonderful things. This is not a dream.

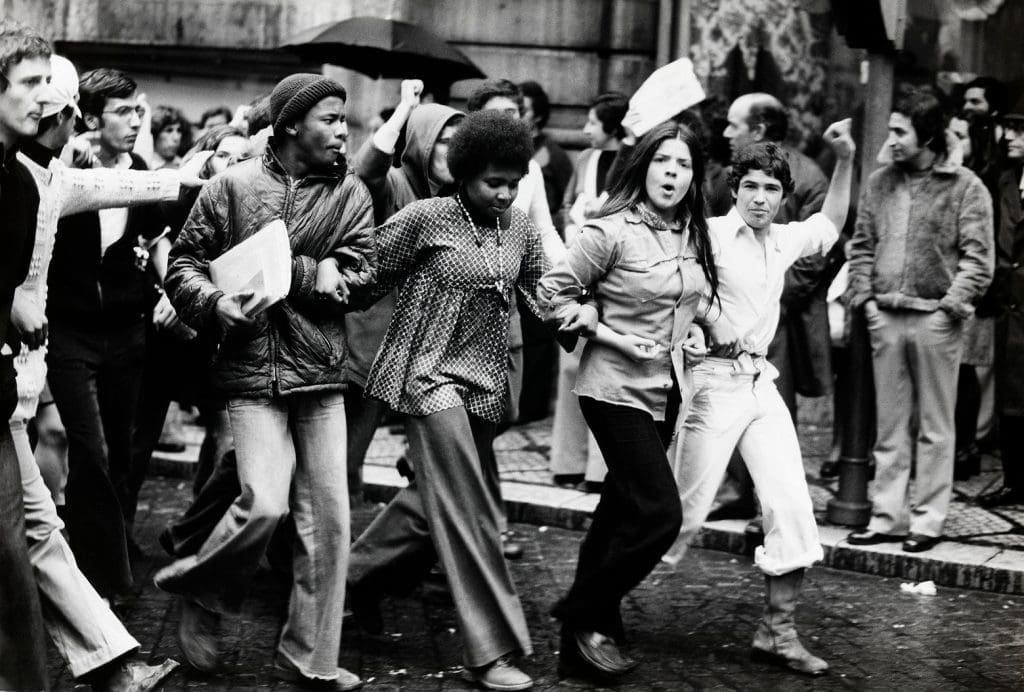

Also worth noting in this current moment of identity and fragmentation in the working class: what we saw in Portugal in 1974-5 was men and women fighting together, black and white people fighting together, shantytowns and highly-qualified workers fighting together; the working class was able to have a universal project of changing society. Compare it to Stalinism in the thirties: the Portuguese road to socialism in ’74 and ’75 was full of liberty. It shows that workers can take power and can organize themselves in liberty.

CM: When there’s a mass movement that takes place, a lot of times you’ll see historians describe it as a spontaneous event, as if it just came out of thin air. But the fact that this leftist revolution did take place—the Armed Forces Movement which initiated the coup was eventually surpassed by revolutionaries who kept moving the revolution farther and farther to the left—that would suggest to me that a left movement had already existed, perhaps underground, in Portugal.

What do we miss when we think of revolutions or mass movements that overthrow dictatorships as something of spontaneity and not something that may have been brewing for quite a long time?

RV: It’s a very interesting question. I believe that a huge part of it is spontaneity. When people go to public places screaming “Down with the fascists” or “End colonial war,” this is completely spontaneous. But during the nineteen months of the Portuguese revolution, political party organizations were absolutely essential—both to the revolution and to the counterrevolution. Party organizations and party leadership—leadership not in the sense of elites, but in the sense of educating cadres, educating leaders—were very important. In the underground, there was already a vanguard party, the Communist Party, faithful to the Soviet Union, with around three thousand members. And there was the same number divided among innumerable small parties—mainly Maoists, but also assorted other parties, pro-Cubans, Trotskyists. These people in the universities, in the industrial schools and technical schools, are very important to understanding the development of the Portuguese revolution.

We have to understand as well that the Socialist Party, faithful to US policy, and the Communist Party, faithful to USSR policy, were very important in how the Portuguese revolution finished with the support of the Socialist Party and the complicity of the Communist Party. Neither the Soviet Union nor the US wanted a socialist Portugal at the time. Meanwhile, revolutionary organizations were quite weak—although none were as strong in Europe as they had been before. Stalinist hegemony had already been called into question in May ’68. Still, in the Portuguese revolution, revolutionary parties managed to run some of the main big factories, and had a huge influence in the public sector. Although they were weaker than the Socialists and the Communists, they reached some influence, which was also new. It helps explain the radicalization of the process.

CM: Why was the revolution peaceful? What should that reveal to all of us about the revolution, that it turned into the Carnation Revolution? Even though it was a military coup, it was a peaceful revolution. What does that tell you about the revolution?

RV: This question is easier to answer than the previous one. Because the army had been defeated in thirteen years of colonial war, the army was not disposed to fighting anymore, much less against their own people. This is very important to explaining the Portuguese revolution. But we cannot say that it was totally peaceful, because the extreme right, and the right wing of the Catholic church—and even the right wing of the Socialist Party—supported violent attacks against left groups and unions when in ’75 they felt they could lose the state.

Violence in the Portuguese revolution was exclusively extreme-right violence—supported, we know now from the research of colleagues in Madrid and Sevilla, by the Franco regime as well.

CM: You write, “I prefer not to use the word fascism to describe the autocratic dictatorship, but I respect the rights and sense of those who suffered under the dictatorship to call it fascist.” Then you write, “Portuguese capitalism was locked into international capitalism. The Portuguese empire became one of the pillars of the free world, a founding member of NATO, and recipient of modern arms and expert advice on techniques of repression. Capital was investing in the shipyards and large modern factories in the industrial belt of Lisbon. The African wars could not have continued for very long without NATO weaponry and equipment. International capital was benefiting from the supply of raw materials from Angola and the sourcing of cheap labor for South Africa.”

What does it say to you about international capitalism when it can be so easily confused with fascism?

RV: This is a much more complex answer. It’s not easy to find documents proving definitively that the dictatorship had the support of international capital. But we definitely have documents showing great relations between the big Portuguese economic groups and the dictatorship. This has been proven; there is no doubt about this and it has been shown by historical research.

What we can say is that all of the five big families of Portugal that controlled the economy at the time had investments from foreign capital that knew they was investing in a brutal dictatorship by investing in Portugal. How can I say this? The Portuguese dictatorship was quite brutal in Portugal, but it was much worse in the colonies. For example, here they used to arrest members of the Communist Party—but they would be arrested and go to court (although some of them were killed). But there were massive killings, we now know, in the colonies. The leaders of liberation movements were killed in the thousands. There was no law there, not even the law of a dictatorship. And all foreign companies knew when they were invested in Angola and when they were invested in Lisbon that they were invested in the nightmare of millions of Portuguese and African people.

We have to say thank you to the liberation movements—much more than thank you, actually, because we estimate that more than 100,000 people were killed in the colonies fighting the Portuguese army over thirteen years. The first freedom we owe to the forced laborers and the liberation movements in Angola and in Mozambique.

Why don’t I call it fascist? Well, Portugal in the colonies was a typical colonial power. No freedom, full oppression, no law. In the metropole, it was what I would call a Bonapartist regime, an extremely tough regime with no liberty—but there were no militias. We have to use the word fascism when there are armed militias used by the elite to fight the unions and the political parties. This was not the case. The state had full power, and it didn’t use militias, except during the Spanish civil war in the thirties. The Salazar regime was afraid that the Spanish civil war could be won by the republicans and that this would destroy the Portuguese regime too, so they built militias in the thirties. But after that, the army was enough to persecute and silence the resistance.

CM: You also write, “What is considered the end of the revolution, the fall of the fifth provisional government, at the end of August 1975, was not the end of the revolution but merely the maturing of the revolutionary crisis—that is, the moment when the political parties, namely the Popular Democratic Party [PPD], the Socialist Party, and the Portuguese Communist Party at the top of society and the Armed Forces Movement (allied together or not) were no longer able to govern, and those from below were no longer willing to be governed. Despite the pretensions of the Socialist and Communist parties, state and revolution drifted apart in 1974 and 1975. Indeed, the revolution was constructed against the state.”

What do you mean by the revolution being constructed against the state? Was the concept of the revolution to not create a state?

RV: Today we see lots of theories coming from the left, from the post-Marxists, defending the idea that we have to fight within the state for changes. In the Portuguese revolution, the workers’ organizations fought the state from their own organizations. It was not from the parliament. It was from workers commissions. They fought the state with power against the state. That’s why we use the concept of dual power.

Even the reforms, the classical reforms in capitalism and the welfare state, were won by organizations that were not inside the state. It is a common debate around all the revolutions of the twentieth century. In fact, what distinguishes a revolutionary period from other periods is that workers are able to organize their own centers of power. That’s why we call it dual power. There is state power and workers’ power. And sometimes there is a revolutionary crisis and one of these fundamental classes has to reach power or be defeated.

What we have seen is very interesting in dialogue with this post-Marxist sector: the bigger reforms in capitalism were not done in parliament, through the electoral process, etcetera—they were done outside the state. The corporations and the state were really afraid of losing power so they made some concessions to the working class, both manual and intellectual.

CM: More than anything, then, was this a revolution against Portuguese imperialism? Was this an antiwar revolution? Did the dictatorship fall because of the colonial wars more than any pressure it might have been feeling from underground leftwing movements?

RV: We have to distinguish two things. There was a democratic revolution, like February in Russia in 1917, and this is no doubt related to the colonial war. So we have to say thank you to the liberation movements—much more than thank you, actually, because we estimate that more than 100,000 people were killed in the colonies fighting the Portuguese army over thirteen years. The first freedom we owe to the forced laborers and the liberation movements in Angola and in Mozambique.

But after the democratic revolution in Portugal, what we saw is that the most dynamic sectors were those that made a social revolution, not just questioning the political regime or the war, but questioning the economic system. The most dynamic sectors were transport and industrial logistics, and also the public sector, public services. And this in turn was an inspiration to the colonies afterwards. We saw a huge number of strikes in ’75 in Angola and Mozambique, inspired by the occupations, strikes, and sit-down strikes in Portugal.

It was a global movement. It was a revolution that arrived from Africa to Lisbon, and it flew from Lisbon back to Africa again—and also flew to Spain, because the dictatorship in Spain could not survive after the Portuguese dictatorship’s fall. The Greek colonial dictatorship could not survive. And even more than that, in my opinion. I developed this idea in this book, and hopefully readers can discuss it because this is just a hypothesis: I believe that the neoliberal policies that were applied in the eighties after the defeat of the miners’ strikes—I believe that the plan was to do it after the oil crisis in the seventies. But they could not do it because the Portuguese revolution (and Vietnam) changed the political reaction to the crisis.

All the revolutions in the twentieth century take place within economic crises, but not all economic crises give birth to a revolution. But what we saw in ’74-’75 in two countries that were not the most important countries in the world—Vietnam and Portugal—became the center of resistance, and it was no longer possible to apply neoliberal policies. They had to postpone it into the eighties. In the eighties, except for the glorious miners and some other sectors, there was no political collective answer to the counter-cyclical measures of the bourgeoisie after the double-dip economic crisis of ’81-’84.

So we have to think of not just what has happened but what could have happened if there were no revolution in this small country in Europe.

CM: Often when there are uprisings, the US mainstream media immediately rushes to the economic conditions that they believe caused the the uprisings to occur. But as you were saying, not all economic downturns lead to revolution. What happens when we just focus on the economics, on the bottom line, on how the people of a place like Portugal are being affected economically? What do we miss in our understanding of the revolution in Portugal when we only focus on the economic needs or demands of the people?

RV: We cannot take this approach linking revolution to economic disaster, otherwise Africa would have had the biggest revolutionary processes, and this is not true at all. We cannot forget revolutions depend on innumerable factors. Economy is one of them, but political organization of the state is too. Do we have a rigid state as we had in Portugal, or do we have a longer tradition of capacity for negotiation with the bourgeoisie, as we had, for example, in England, and a capacity for mediation between workers and the state? We also have to see who the working class is. Is it mainly industrial working class, mainly qualified working class, or mainly rural, poor working class? There are innumerable factors to analyze a revolution.

Not all economic crises lead to a revolution. We had a big example in 2008. This economic crisis did lead to revolutionary processes in the Arab Spring, but in very backward countries with huge sectors of informal and rural labor—as we had in Libya and Tunisia and Egypt. And unfortunately these countries were alone. There was no revolutionary process in Europe or in the US supporting these countries, so it was easy for the counterrevolution to defeat the wonderful revolutionary process of the Arab Spring.

We were happy. We found ourselves without fear. We found out that problems exist but we can solve them. There was a possibility of creativity, autonomy, changing the world. When my fellows had strikes and changed the world, they changed themselves. This is extremely beautiful. People changed. They became better people when they tried to change the world.

But apart from the Arab Spring (which was defeated with fundamentalism and with US intervention and European intervention), there was no other revolutionary process against the awful counter-cyclical measures of the elites, of the bourgeoisie, in order to rebuild their profit standards. So the working class suffered defeat in 2008. I have no doubt about this. It’s not an eternal defeat, but it is a defeat when the bourgeoisie is able to cut twenty or twenty-five percent of incomes and make massive layoffs and massive cuts in public sector salaries and social services. The working classes were defeated.

We have to think why. Why? What was the role of social democratic parties? What was the role of the bureaucratic unions? All revolutions of the twentieth century took place during or after an economic crisis because the process of economic crisis is not just an opportunity for the working class—it’s a crisis in the dominant classes. It’s a crisis in the elites. The cake is not as big anymore to divide among the fractions of the bourgeoisie. So there is a crisis of the state, there is a weakness of the state during economic crisis.

CM: You write, “The banks were nationalized and expropriated with no compensation whatsoever and the right to free time was absolutely pivotal. Take the case of the demonstration by bakers working long hours whose slogan was, ‘We want to sleep with our wives!’ People won not just price freezes so that they could have decent meals, but the right to leisure and culture. They also won the right to housing, indeed by occupying vacant homes that were destined for speculation. Even judges sometimes backed them, as in the city of Setúbal. I’ll remind you that today in Portugal there are 700,000 vacant houses owned by real estate funds which do not pay taxes.”

Is what the Portuguese revolutionaries fought for still being fought for in Portugal today? And for that matter, is it what the left is still fighting for globally?

RV: I believe the demands are more or less the same in the sense that people want a safe job, they want to work, and they want to have security and health and education and what is basic to survive.

The consciousness of the people, unfortunately, I think is not as it was in ’74-’75. People take debt for granted. They have to work extra time to be able to pay their accounts. They take for granted that their children cannot eat the best natural fruits and they give them chocolates because chocolates are cheaper. They take for granted that we don’t have cities with huge green parks where the working classes can play; the children are shut in at home with an iPhone or with a game. There has been a degradation of the living conditions of the working class.

I coordinate studies on burnout among the workers in my university. People are extremely depressed, demoralized, and alienated in their jobs. And their first tendency is to blame themselves. It is not to explain the organization of labor that makes people unhealthy, and how to fight it, and how to organize. There has been a depoliticization of Portuguese society, and there is this idea that the parliament and the parties can solve everything for us. There is not a sense of political activity, political mobilization. Even political discussion is very weak compared to 1975.

CM: You told David Broder in an interview at Jacobin that you have written more than ten books on the revolution in a decade of research, and you always hear people saying the same thing, that the days of revolution were the happiest days of their lives. “In these two years, human beings were reunited with their humanity. This legacy still lasts today, and it is the only one that can save us from the abyss of the present.”

How does the Portuguese revolution suggest we reunite with our humanity?

RV: This is the biggest lesson. It’s absolutely true. I looked through pictures of the Portuguese revolution in eight different archives in Europe, and in all the pictures people are smiling. They are very poor, and they are smiling—because they are fighting, because they believe there is hope, because they believe they can change things. It’s the self-determination process that Perry Anderson theorizes. It’s being alive. It’s absolutely wonderful to see that people were happy at that time.

I have to say this: people were poorer then than they are nowadays. But they were happy. Not because when people are poor they are happier—this is of course a ridiculous explanation—but because there was hope. There was a sense of collectivity. There was a sense of cooperation. There was a sense that we are changing. There was a connection between manual and intellectual work. There was almost no division between leaders and rank-and-file—all rank-and-file workers could become leaders. We were not scared of being human and behaving as humans. We were not behaving as we behave nowadays; we have huge competition that makes us sick. It’s absolutely terrible. We don’t see other people, our colleagues at work, in our neighborhoods, in our country, in international matters.

I was not alive at the time, but I’m sure we were happy. We found ourselves without fear. We found out that problems exist but we can solve them. And there was a possibility of creativity, autonomy, changing the world. When my fellow Portuguese—and others; so many international people were here. When they had strikes and changed the world, they changed themselves. This is extremely beautiful. People changed. They became better people when they tried to change the world.

There is a good thing we have to learn from the Portuguese revolution. We are not going to be happy because we are going to yoga at seven o’clock in the morning when we then go to an awful job that makes our personal lives terrible. We cannot adapt to terrible conditions. We have to change terrible conditions in order to change ourselves.

CM: You write, “The revolution was to be defeated with a coup d’etat on 25 November 1975, which in turn instituted a representative democracy within the framework of capitalism, which inevitably eroded social rights. The defeat of the revolution put an end to fundamental democracy, particularly in the barracks, factories, companies, schools, and neighborhoods. There is nothing unusual about this, but it may be that Portugal is the first example of the success of defeating a revolution by replacing it with establishment of a representative democratic regime.”

Why is the eroding of those rights inevitable under representative democracy within a framework of capitalism? Did the Portuguese revolution prove that representative democracy is not democracy?

RV: Yes. Representative democracy is a form of regime where democratic rights, political rights, are assured by the state, but the dictatorship of companies, in labor, persists. There is no democracy in companies. And without democracy in what we produce, we cannot be free.

CM: Thank you so much for being on our show this week.

RV: Thank you.