Antinote: this is another post that is long overdue, an English translation of one of our earliest salvos, an essay we republished from the blog of a leftwing party activist in Hamburg, Germany, at a time when that city was experiencing intense local conflict. Once again, there are parallels and lessons to be drawn with present-day struggles in comparable situations—certainly in Minneapolis, and probably wherever you are, too.

“We’re all staying!”

by Florian Wilde for his blog

9 January 2014 (Antidote’s post in German – original no longer available)

A group of around three hundred West African refugees arrived in Hamburg from Libya in early 2013. After a perilous trip across the Mediterranean, their journey brought them first to the Italian island of Lampedusa, so they gave this name to their group. The authorities in Hamburg, however, citing EU regulations, refused to provide stable accommodations for the refugees and attempted to expel them from the city. But the refugees didn’t want to go. And where to, anyway? They decided to stay, to go public, and to fight for their rights.

They were met with a spontaneous outpouring of sympathy and solidarity from many segments of the population. Churches opened their doors; so did mosques (if somewhat less publicly). Leftist alternative social centers and co-living projects also took on some of the refugees.

Some eighty of them found shelter in the church of St. Pauli, right next to the formerly squatted buildings of the Hafenstrasse as well as Park Fiction, one of the parks that had been established in self-organized fashion by residents to defend neighborhood space from speculative development (and which had been renamed Park Fiction in solidarity with Istanbul’s Gezi protests in 2013). There, residents organized several Welcome Barbecues for the refugees. Every day, groceries and blankets were brought to the church to support the refugees. The soccer team FC St. Pauli donated drinks and fan attire, as well as free tickets to home games for refugees. Labor organizations Ver.di and the GEW organized a welcoming party in their union hall.

The refugees collectively joined Ver.di, through which they came under the protection of labor law. After rightwing fraternities started perpetrating racist violence against the refugees, a well-known neighborhood bouncer volunteered to stand watch in front of the church overnight for weeks. The refugees played a crucial role in the large “No profit from rent!” demonstration organized by Hamburg’s Right to the City coalition on 28 October 2013.

Still, while the refugees experienced much solidarity from the population, from leftist groups and unions, the socialist-led city government stood by their hard line: that the presence of these refugees ostensibly violated EU regulations and they must leave the city. When more than 270 refugees drowned in a boat catastrophe off the coast of Lampedusa in early October, solidarity among Hamburg residents only grew—nonetheless, the city senate did not budge from its hard line. Quite the opposite: it issued the refugees an ultimatum, demanding they report to city authorities by 11 October 2013 to get registered.

When the ultimatum expired, the police began a massive stop-and-check operation with the goal of detaining refugees and preparing them for deportation. A spontaneous wave of protests rose in response: the very same evening, over a thousand people took to the streets of Altona—spontaneous, angry, and very loud. Same thing the next day, and the next.

In the Rote Flora, the squatted autonomous center in the Schanzenviertel, a general assembly was called to discuss how to deal with the police checks. Alongside the meeting, over five hundred people once again marched through the Schanze calling for refugees’ right to remain. The general assembly resolved to issue an ultimatum of its own to the Hamburg city senate: if they did not stop police checks on refugees in a matter of days, street protests would escalate. “We will no longer limit ourselves to legal forms of protest, when people are drowning daily in the Mediterranean and the Hamburg city senate—in spite of international criticism—uses this as an occasion only to put more pressure on refugees here.”

Once this ultimatum to the senate expired, more than a thousand people gathered in front of the Rote Flora and marched unpermitted through the Schanzenviertel. After only a few hundred meters, the demonstration was violently attacked by the police. Stones, bottles, and fireworks flew in response. Small groups kept up the protest for hours.

Just one day later, on Wednesday 16 October, once again around 1,100 people marched through the city center, departing from a refugee protest encampment in front of the main train station. At the same time, the tenth grade class of a St. Pauli high school released a call to action announcing they would open the school’s gym to refugees. When the senate made clear in response that the students were risking prosecution, the parents’ association at the school released their own call in which they declared their solidarity: “We fully and unreservedly stand behind our students. We’re proud that our children are facing down the senate. We call all citizens of Hamburg to acts of disobedience against the city’s racism!”

On 25 October nearly ten thousand people heeded a call from the FC St. Pauli fan scene and joined a solidarity march from the stadium to the church of St. Pauli after a game. A week later, on 2 November, some fifteen thousand people took part in the largest demonstration yet in support of the refugees, and weekly demonstrations continued after that.

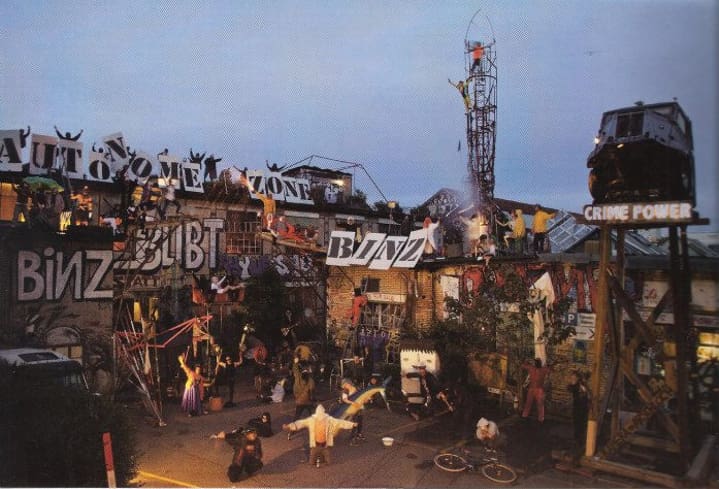

The protests in Hamburg drew some of their strength and dynamism from their close association with the Right to the City movement, which was fighting against the privatization of public spaces, for cheaper housing, against commercialization, and for free space for all—including refugees, of course. In Hamburg there is a long tradition of leftwing neighborhood political struggles and movements; in the 1980s and early 90s the Hafenstrasse, the Rote Flora, and many more buildings were squatted and maintained as alternative living projects. The Rote Flora has existed since 1989 as a squatted autonomous center without any kind of contract. This infrastructure has underpinned many movements over the years and into the present day. Of course some projects get evicted and shut down, such as the trailer park “Bambule” in 2002. Nonetheless when that happens, months of protest—in some cases quite militant—follow, prompting the city to back off any further eviction plans.

When rents in Hamburg exploded in the late 2000s, resistance redoubled in the form of a new Right to the City network, which was able to mobilize many thousands of people to fall demonstrations “Against Rent Insanity” on a yearly basis, from then until now. The minute investors’ plans for inner city areas become public, there is protest: residents hang protest flags out their windows, activists symbolically squat buildings and organize informational events—currently, for example, against the threatened demolition of the so-called “Esso” buildings on the Reeperbahn. These protests don’t succeed in preventing investors’ plans entirely, but under this pressure from the movement, every political party in Hamburg finds itself compelled to center their election campaigns on the rent question and to promise massive housing construction programs. And the movement can claim actual concrete achievements as well: in the summer of 2009, artists occupied the Gängeviertel, two tiny streets in the old city protected as historical landmarks, to prevent their demolition by a developer. Ever since, the area has existed as a self-managed non-commercial co-living and cultural project.

In late summer 2013, word spread that the Rote Flora’s own existence as a squatted leftwing autonomous center was being threatened: having been sold years ago by the city to a developer, this owner had now announced the intention to turn the Flora into a commercial music club. Every political party—all the way to the Christian Democrats—has spoken out against any alteration to the Rote Flora, arguing that it belongs, just as it is, to the Schanzenviertel. Because it’s clear to everyone: the Flora has significance far beyond Hamburg. Its eviction would lead to heavy protests and come with immense financial and political costs. So politicians are balking. Nonetheless it is possible that the investor-owner could get a court to enforce his interests and therefore an eviction of the Rote Flora. Ever since the threat to the Rote Flora became known, numerous activities have unfurled from there which also unfailingly relate back to the refugee struggle.

Under pressure from the protests, the city senate has in the meantime voted to allow heated shipping containers to be installed in the St. Pauli churchyard for refugees to sleep in during the winter. Still they continue to refuse the refugees’ actual demand: a collective solution including the right to remain for the whole group.

Street protest up to this point has been carried out essentially by leftwing autonomous groups, the party Die Linke, and some union rank-and-file. Concrete solidarity with refugees exists primarily in neighborhoods long characterized by leftwing movement, like St. Pauli, Altona, and Sternschanze. In other places, the senate’s posture finds more acceptance, buoyed in part by widely held racist sentiment. In order to actually force the social democrats, who hold an absolute majority in city government, to change course, it will be necessary for the movement to keep the pressure on, to turn the pressure up, and to pull in other parts of the left spectrum like the social democratic and Green milieus. This has already begun, looking at the mass demonstration on 2 November.

Since the end of December 2013, the situation in Hamburg has continued to heat up. The Rote Flora had issued a countrywide call to a mass demonstration on 21 December under the motto “Here to Stay: Refugees, Esso-Häuser, Rote Flora – Wir Bleiben Alle,” and ten thousand people had shown up. Around half had taken part in a giant autonomous black bloc spearheading the march; thousands more marched with the colorful “Right to the City” bloc, which was organized by neighborhood initiatives and leftwing radical groups and was also supported by Die Linke in Hamburg. After only a few meters, the demo was stopped by police, who attacked with batons, water cannons, and tear gas, and was ultimately dispersed. The autonomous bloc tried with all they had to ward off the attack. What followed were the heaviest street clashes Hamburg had seen in years. Thousands of people tried in various ways to assert their right to demonstrate against state power. Even before the demo set out, there had been an attack on a police station by a group of masked people.

An alleged second attack on 28 December led to a massive media frenzy against the movement and “leftwing violence.” The police used the pretext to declare broad swathes of Altona, St. Pauli, and the Schanzenviertel a “danger zone” in which arbitrary stops, ID checks, and expulsions can be enforced at any time—a grave threat for the Lampedusa refugees, among whom many had not wanted to register with authorities. Die Linke protested against the danger zone and attempted to counter the frenzy in the media, for which the party was harshly assailed by the rightwing.

In early January it came to light that the police had fully invented the second attack on the station, obviously to legitimize the imposition of emergency measures (establishing the danger zone). Since then there have been spontaneous protests every evening, with hundreds of people standing against the curtailing of their civil rights in the “danger zone.” So the city, in addition to the issues of refugees, rent prices, and the Rote Flora, now has an additional issue to deal with: the defense of civil rights vis-á-vis the state.

The example of Hamburg shows how antiracist protests against European asylum policies can link up with local struggles like the fight around skyrocketing rents and the right to the city, lean on long-tended and well-entrenched leftwing neighborhood political nodes, and receive parliamentary and extra-parliamentary support from parties like Die Linke. The confluence of all these various movements and actors has formed in Hamburg, over many years, a leftwing alternative political milieu based on a robust infrastructure of social centers, former squats, and political groups with ties to unions, the left political party, and left-liberal media.

Florian Wilde is a member of Die Linke party leadership

Translated by Antidote

Featured image: tile art in the Rote Flora, 2015. It says “Danger Zone.” Source: Flora Baut (noblogs)