AntiNote: Last week was the tenth anniversary of perhaps the most shocking and gruesome of the manifold crimes committed by the Assad regime in Syria: the sarin gas attacks in Eastern Ghouta, suburban Damascus. An elder sibling website to ours, Linux Beach, posted a thorough, link-rich retrospective on the anniversary itself, 21 August, which laid out the significance of this heinous massacre in all its geopolitical and historical dimensions—long story short, it really changed everything, for everyone, for the worse.

Although this fact has been repeatedly well-articulated and explained, in these pages and certainly on other far more important platforms, it remains unrecognized in wide swathes of discourse and scholarship. This is partly because it happened in a “peripheral” country to “peripheral” people, and partly—mostly—because it has been lied about so massively and persistently. Indeed the flood of lies is itself emblematic of one of the ways everything changed that day—reality itself was fractured.

In addition to the various observances of the anniversary like the one mentioned above, there appeared on 21 August 2023 two especially poignant outcries from survivors of these and other chemical weapons attacks in Syria which attempt to address this fracture directly. On the one hand, an open letter was posted on Al-Jumhuriya (“A platform for Syrians to own their discourse”) addressed to Western academics and institutions, condemning their apologism, revisionism, and racism. Simultaneously, the same group of authors launched a counterinformation website featuring survivor testimony and art alongside careful illuminations of the various tactics of denial and disinformation that have been used over the last decade to sow confusion and resignation about the truth of these repulsive crimes.

With the kind permission of the activists behind “Do Not Suffocate Truth,” the source of this material, we present here a taste of their website’s analysis – their deconstruction of propaganda narratives as well as truth-suppression tactics – followed by the open letter. We do so in solidarity with survivors, refugees, exiles, prisoners, and their families in and from Syria. We have edited the texts very lightly for clarity.

From the heart of Turtle Island, in a nation-state founded on multiple genocides that are ongoing, we understand that the denial is part of the genocide, and is as much a part of the violence as the killing itself. With all our energy, we resist this kind of brutal, oppressive denialism in all its forms and everywhere it appears.

Denial Messages: Chemical Attacks in Syria

by Do Not Suffocate Truth

21 August 2023 (original post)

Since using them for the first time in 2012, the Syrian regime and its allies continue to deny having utilized chemical weapons, and they deploy various narratives to this end. These denials can be divided into four categories that sometimes overlap. The following is a rebuttal to each of them based on statements issued by the regime and its Russian and Iranian allies.

Denial messages:

- Categorically deny the occurrence of chemical attacks

- Accuse opposition forces of carrying out the attacks

- Question information about the attacks

- Question the entities that collect and analyze evidence and information

These four types cover most of the statements made by the regime and its allies in this regard, and are considered the main denial strategies used. The following is a respective review of some of the positions and statements that fall under these categories.

1. Categorically deny the occurrence of chemical attacks

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, the regime and its allies have frequently used this method after committing massacres. After the regime began carrying out chemical attacks against areas outside its control, the media narrative of the regime and its allies always began by denying that the chemical massacres had ever occurred.

An example of this is the statements of the Syrian minister of information, Omran Al-Zoubi, regarding the chemical massacre committed by the regime on 21 August 2013 in Eastern Ghouta, in which 1,144 people were killed and 5,935 were injured. He said: “The pictures and information that were broadcast have all been fabricated and prepared beforehand.”

As for the Russian foreign ministry, it had the following to say about the massacre: “There is compelling evidence that pictures of the chemical attack victims were fabricated,” without publishing any evidence for this claim. Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif also denied that a massacre had taken place, in his statement at the time.

During the UN security council meeting held in April 2021, the Syrian regime’s representative to the security council, Bassam Sabbagh, said: “Syria confirms, once again, that it did not use chemical weapons and that it worked credibly and transparently with the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and the United Nations to meet its obligations.”

In the second week of April 2018, pro-Assad media outlets, including Russian Channel 1, published pictures claiming that the chemical attack in Douma in 2018 had been an act. It later became apparent that these photos were taken from the filming of loyalist director Najdat Anzour’s movie, Man of the Revolution. In the third week of that same month, Russian media also published footage of what it described as scenes of a fabricated chemical attack on Douma in 2018. Again, it turned out that they were clips taken from a short film by the pro-opposition director Hammam Al-Hosari filmed in 2016.

2. Accuse opposition forces of carrying out the attacks

While the Syrian regime and its allies in Russia and Iran always deny the occurrence of chemical weapons attacks, they are also quick to accuse opposition factions of being responsible for the attacks, especially after denying their occurrence becomes untenable due to the abundance of evidence.

Back to the Ghouta massacre in the summer of 2013: Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif denied the massacre initially, but then added: “If the incident happened, then the opposition certainly did it.” As for the Russian deputy foreign minister, he said: “Moscow has received materials implicating opposition militants in the chemical attack from Damascus.”

In statements by the Russian foreign ministry, it was claimed that “the missiles loaded with sarin, which caused the massacre, were launched from opposition-controlled sites.” Later, the Guardian newspaper published a French intelligence report that included forty-seven satellite videos showing the moment when chemical missiles were launched towards Eastern Ghouta—from areas controlled by the Syrian regime.

Contrary to statements by the Syrian minister of information, who categorically denied the massacre, the political and media advisor to the president of the Syrian regime, Buthaina Shaaban, said that “the victims of the chemical massacre in Eastern Ghouta are children. The opposition forces brought them from the villages of the Syrian coast to Eastern Ghouta, where they killed them with chemical weapons.” In her statement, Shaaban ignored the siege imposed on Ghouta by Syrian regime forces, and the nearly four hundred kilometers separating Eastern Ghouta from the villages of the Syrian coast. These two facts alone are sufficient to prove the falsehood of these claims.

Afterwards, speaking about the 2017 sarin gas attack on Khan Sheikhoun, the representative of the Syrian regime to the United Nations, Bashar al-Jaafari, said: “The opposition forces were able to smuggle chemical weapons from neighboring countries, and they were the ones who used them in Khan Sheikhoun.” Or, the parties who dumped the Syrian stockpiles at sea left part of it and and used it in Syria to pin the attack on the Syrian regime and allege that the formula used in the attacks was made of the Syrian precursor.

As for the Russian defense ministry, it said the following about the incident: “Syrian government forces bombed a chemical weapons depot in Khan Sheikhoun.” Subsequently, the Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM), which was established by a UN security council resolution, proved that regime forces had been responsible for that attack.

3. Question information about the attacks

The Syrian regime and its allies resort to this method in order to further misinform, especially in light of the lack of evidence that opposition factions were responsible for the attacks. They question the veracity of the information provided by opposition parties about the crime, the number of victims, the location of the photographs, the symptoms apparent on the injured, the behavior of the injured and paramedics, their first aid methods and tools, the means used to document, and other details.

All of this to claim that the occurrence of the chemical attack in the manner claimed by the anti-regime parties is doubtful in the first place, and that the videos and documentation of the attack are plays orchestrated by these parties in advance, casting a cloud of misinformation and ambiguity on the issue.

On 12 April 2018, the Russian foreign ministry issued a statement regarding the chemical weapons attack on Douma in which it questioned the veracity of the information related to the attack, stating: “At first, it was said that thousands were killed, then the numbers became more modest. The information spread by the opposition includes many contradictions regarding the time and place of the attack.” The statement described the video footage as “unbelievable, showing children and adults pouring water on each other.”

After the issuance of the third JIM report of the of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons [OPCW] and the United Nations in August 2016, which conclusively proved that the Assad regime had used chemical weapons twice, the Syrian regime’s representative to the United Nations, Bashar al-Jaafari, said: “The conclusions contained therein are not convincing because they are totally based on the statements of witnesses presented by armed terrorist groups or environments that incubated them.”

In response to the same report, the Russian ambassador to the United Nations, Vitaly Churkin, questioned the results, saying: “A number of issues still need to be clarified before accepting the results,” without clarifying what those issues were or whether the Russian side had written to the JIM about them.

After an additional JIM report was issued which proved that the Syrian regime had used sarin gas when targeting Khan Sheikhoun, the aide of the Russian representative to the United Nations wondered: “How can a report condemning al-Assad include phrases such as “likely,” “probably,” and “apparently?” The representative of the Syrian regime at the United Nations said: “The investigation committees are biased, politicized, and unethical. They excelled at their job by using false witnesses, open sources, fabricated evidence, manipulation of information, and cunning language.”

Russian Deputy Representative to the United Nations Vladimir Safronkov, when speaking about the Syrian regime’s attack with sarin gas on Khan Sheikhoun, questioned the occurrence of an “attack of this kind” and described the images shared on the internet by activists and aid workers as “fabricated” despite the emergence of dozens of children who died due to symptoms associated with difficulty breathing upon inhaling toxic gases.

4. Question the entities that collect and analyze evidence and information

After condemnations are issued against the Syrian regime by the investigating international organizations and committees, and after the Syrian regime’s involvement in the use of chemical weapons is proven, the Syrian regime and its allies are quick to question the integrity and professionalism of these organizations, entities and committees.

The Syrian regime describes Human Rights Watch as a “Western tool” due to its reports indicating its implication in committing massacres with chemical weapons. The same method is used by Russia to challenge the results of investigations issued by international bodies and organizations.

For example, following a “leak of investigators’ correspondence” about the chemical attack in Douma, the Russian foreign ministry spoke about the OPCW, saying: “There is a feeling that the originally abnormal conditions inside the organization continue to deteriorate sharply.” Meanwhile, the head of the Russian delegation at the Organization’s conference, Oleg Rezantsev, said: “The report published by the organization in March 2019 (regarding the chemical attack on Douma) distorts reality and is based on the opinions of people hired from outside the organization.”

The Russian foreign ministry described the results of the investigation into the 2017 chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun as “superficial, unprofessional, and amateurish work.” The representative of the Syrian regime to the United Nations, Bashar al-Jaafari, described the JIM report as “partial and unprofessional,” adding that the investigation’s framework relied on “false witnesses, open sources, fabricated evidence, and manipulated information.”

Among the organizations that the Syrian regime and its allies are constantly attacking is the White Helmets (Civil Defense), which is responsible for rescuing the injured and recovering the dead after destructive bombing campaigns are carried out by Syrian regime forces and those of its Russian and Iranian allies. Russia has led a massive campaign to demonize the White Helmets and depict them as being part of terrorist organizations, especially after a movie made the organization famous and showed the nature their work and its hazards.

France 24 prepared a report in which it refutes these allegations, demonstrating what is true, what is false and what is uncertain.

After the release of the first JIM report on April 8, 2020, which held the Syrian regime responsible for the chemical weapon attacks on the town of Latamna in Hama in 2017, Russia was able, through its veto, to prevent the extension of the Joint International Mechanism’s investigation. It attacked the report, the OPCW, and its investigating team, saying that it “exceeded the powers of the Security Council” under the “pressure of countries” that it did not name. Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said at a press conference that “A small circle of countries with an interest to do so imposed the formation of an investigation team in violation of the basic provisions of the Convention on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and the recognized norms of international law.”

Russia and the Syrian regime also took advantage of an article published by the British newspaper the Daily Mail about the correspondence among some investigators of the fact-finding mission in Douma. This correspondence discussed manipulation of the results of the investigation, and according to the leaks, an unidentified investigator expressed his “great concern” in an email, stressing that the organization’s report “misrepresents the facts” and reflects “unintentional bias.” Russia and the Syrian regime have worked to promote these leaks with the aim of demonstrating that the report of the fact-finding mission issued in 2019 is inaccurate and unreflective of reality in order to strengthen the narrative that the attack on Douma had been fabricated.

Commenting on the leaks, the head of the OPCW, Fernando Arias, said, “Inspectors (A) and (B) are not whistleblowers. Rather, they are two people who could not accept that their views were not supported by evidence,” stressing that the behavior of these inspectors “is more egregious because they clearly have incomplete information about the Douma investigation.” Arias also announced that an internal investigation would look into the leak of an internal document, as well as confirming the organization’s findings regarding the Douma attack on April 2018, which killed forty people.

Conclusion

It is clear from reviewing examples of the four types of denials that the discourse of the regime and its allies does not aim to reveal the truth about any of the chemical attacks. Indeed, it aims to confuse, mislead, and make it extremely difficult to ascertain the truth. The regime and its allies have no unified narrative; instead, their narratives are intertwined and sometimes contain contradictory accounts and allegations that are meant to do nothing but hide the truth under layers of lies.

* * *

Means of Stifling the Truth

by Do Not Suffocate Truth

21 August 2023 (original post | PDF version)

After every chemical massacre they commit, the Syrian regime and its allies in Russia seek to hide evidence of the crime, erase traces, and tamper with the case. They use many means to achieve these goals, including:

- Tampering with evidence directly and indirectly

- Obstructing the work of investigative committees

- Intimidating witnesses

- Perjury

- Media disinformation

1. Tampering with evidence

Direct tampering: This is what the regime and its allies do after taking control of the crime scene. They erase their traces, hiding the effects of projectiles, chemically treating the area by disinfecting the site targeted and spaces where first aid was given to the injured, and changing the features of the area by, for example, digging up graves or removing victims’ corpses and replacing them with intact ones.

Indirect tampering includes preventing the inspection committees from reaching the crime scene later by bombing the crime scene and everything that could serve as evidence of the crime, such as hospitals, ambulances, cemeteries, and the like.

2. Obstructing the work of investigation committees

Every time the investigative committees and inspection teams plan to enter Syria, the Syrian regime and its Russian allies strive to mislead the investigators and put various impediments to the work of these teams and committees. These impediments include delays in responding to correspondence and granting entry visas to inspectors. They also seek to restrict these teams’ access to the areas attacked, especially since regime forces control the crossings and roads leading to the opposition-controlled areas they target with chemical weapons. The members of these committees and teams were at times intimidated, as happened in Douma when a UN security team reported gunfire at the site where the inspectors had intended to go.

3. Intimidating witnesses

The Syrian regime has been systematically committing crimes against the families and the property of peaceful activists since the beginning of the revolution in 2011. These include arbitrary arrests and detention, burning or confiscating property, and, in some cases, even murder. Thus, many activists resort to concealing their identities for fear of their relatives being subjected to the regime’s viciousness.

After the regime committed chemical massacres, many witnesses and survivors were keen to avoid appearing on media outlets to talk about what had happened, especially since the regime was sending threats through its agents, such as insinuations that their relatives residing in areas under regime control would be harmed if those witnesses and survivors spoke out about the chemical massacres.

4. Perjury

The Syrian regime and its Russian allies have exploited those who reached compromises [“reconciled”] with them in the areas they had regained control of, using them as false witnesses to the chemical weapons crimes by forcing them to give altered testimonies that contradict the actions they took or testimonies they provided when the chemical crimes occurred.

The Russian side forced doctors from Douma who had reached settlements with the Syrian regime to give false testimonies about the chemical massacre in Douma, and took them to the Hague so they could make statements denying the chemical massacre ever occurred, even though they were among the medical teams that tried to rescue the martyrs and the injured. The doctors had no other choice, since their families live at the mercy of the Syrian regime’s security apparatuses.

In Eastern Ghouta, the regime forced media and revolutionary activists to go on media outlets and deny the occurrence of the 2013 chemical massacre in Ghouta, although some activists had taken part in documenting the crimes with their cameras and had borne witness to them.

5. Media misinformation

The Russian side has established a media machine composed of Russian and foreign journalists and local media professionals affiliated with the regime. This agency worked to publish swaths of misleading media reports to influence the search engine results of research into chemical weapons and to mislead international public opinion.

In addition, Russian media channels have resorted to taking excerpts from dramatized reenactment films, showing behind-the-scenes clips, pointing to gaps, and claiming that these were the clips shared by the opposition to implicate the regime in chemical weapons attacks. The aim was to influence global public opinion, taking advantage of the fact that many are unfamiliar with the reenactment films that address the question of chemical attacks.

In the same context, the Syrian regime arrested several female teachers from Ain Tarma after taking control of Eastern Ghouta in 2018, and coerced them (with threats) to confess that they had trained school children to perform and play roles during the chemical warfare in Ghouta in 2013. The teachers were also forced to appear on media outlets to talk about this. The Syrian regime also arrested several children who had been injured by chemical weapons in Ghouta and whose photos had been viral on social media in order to hide them from public view and prevent them from traveling—including the child who said the famous phrase “I am alive.”

Resisting the Denial of Assad’s Allies & Apologists for His Greatest Crime

An open letter addressing denialism in academia, on the tenth anniversary of the Ghouta chemical massacre

by Do Not Suffocate Truth, first published by Al-Jumhuriya

21 August 2023 (original post)

We are reaching out to you on behalf of the «Do Not Suffocate Truth» campaign, an initiative founded by survivors of chemical weapon attacks in Syria, as well as Syrian activists who have been forcibly displaced or who have fled from oppression and imprisonment.

Our campaign emerged during the prolonged siege of Eastern Ghouta, where many of us were trapped for the fifth consecutive year in 2018. Amid the relentless shelling and forced displacement we faced during our final days there, the Syrian regime launched a chemical weapons attack on Douma, a town in the Damascus countryside, on 7 April 2018. This was not the first time the regime had used chemical weapons. Prior to the Douma attack, the Assad regime had carried out dozens of similar attacks on civilians, the most significant being the Ghouta chemical massacre on 21 August 2013 — a tragedy now entering its tenth anniversary.

During that period, as we grappled with chemical attacks and forced displacement, we encountered skepticism propagated by certain academic and journalistic circles. In the early stages of our forced displacement, we faced challenges in terms of limited resources, energy, and time to effectively counter this growing denialism and expose its proponents.

In our mission to uphold truth, ensure accountability, and prevent the recurrence of atrocities, we have committed ourselves — seeking refuge in other nations — to confronting the denialism surrounding the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons in Syria. As survivors of these war crimes, we understand that denying these events not only extends the impact of the massacres but also justifies these actions, clearing those accountable – including the Syrian regime and its allies, namely the Russian state. This denial normalizes their heinous acts and violence, allowing for their repetition without repercussions or accountability — both within Syria and beyond, across multiple conflicts and wars.

We consider this message to your university, which includes academics who have directly or indirectly contributed to the denial of the use of chemical weapons by Assad, as an accountability measure. This message originates from the credible and reliable sources of the massacre and is directed towards those who want to research and study it.

These academics, by denying the occurrence of the chemical massacres, engage in a form of cognitive violence against us Syrians who strive for freedom, justice, and democracy. This cognitive violence hinges on a complete disregard for the truth and the lived experiences of communities subjected to political oppression and suppression. They leverage their knowledge to access financial, academic, and networking resources. Furthermore, they invalidate the victims of these attacks, suggesting that victims are incapable of articulating their own experiences and suffering. This perpetuates the phenomenon of the ‘foreign expert,’ someone presumed to be more knowledgeable about a nation’s affairs than its own residents, activists, thinkers, and survivors. Such actions contribute to the stigmatization of victims who are framed within the context of counterterrorism efforts and the refugee crisis, ultimately perpetuating racial stereotypes. We convey this message to you in order to advocate for the political competence and research abilities of Syrians.

We fear that denialism could reinforce anti-refugee policies, leading to racism and deportations. It reinforces the Syrian regime’s narrative that Syria is a safe country free from chemical weapons, barrel bombs, or detention facilities. Governments with discriminatory policies might exploit this reinforced narrative to justify deporting refugees or leaving them adrift in perilous refugee boats.

Certainly, the machinery of Russian propaganda, a cornerstone of Russia’s policy of occupation and intervention in Syria, has significantly contributed to denialism regarding the usage of chemical weapons. Both the Syrian regime and Russia were under no obligation to maintain a consistent narrative, as denialism does not require logic, empiricism, survivor accounts, or international investigations. Instead, it thrives on fostering chaos and sowing doubt. The denialist narrative has undergone a series of transformations that render it unrecognizable from its previous iterations. What began as outright denial was followed by claims that the victims gassed themselves, which later morphed into accusations that other nations targeted Syria with these weapons to justify their intervention. It has even delved into intricate technical details about the types of gases used and debates about the exact number of victims, alongside other deliberately unproductive debates.

The efforts to deny the use of chemical weapons went beyond mere propaganda. They were coupled with tactics that included intimidating witnesses and their families, manipulating graves and evidence, and exerting pressure on investigative committees.

As Syrian activists, intellectuals, and survivors, we faced all of this not only against a major imperialist state currently waging wars in multiple countries but also against academics in democratic countries who played a noticeable and disappointing role in whitewashing the crimes we have suffered, especially those related to chemical weapons.

At times, this denial arises from ideological biases that favor Russia and the Syrian regime, thereby legitimizing their human rights violations under the guise of counterterrorism or anti-imperialism. Proponents of these belief systems often overlook the reality that Russia is an imperialist nation engaged in wars in various countries. As a result, Syrians are reduced to mere tools for their intellectual triumphs against the United States and the West.

At other times, the denial is fueled by intellectual laziness and inadequate research despite the plethora of available sources. It also entails disregarding, perhaps intentionally, the voices of Syrians, including public intellectuals and direct witnesses of chemical weapons usage in Syria.

In light of this, we call upon your university to conduct a comprehensive examination of the colonial production of knowledge and the impact of denialism on those affected by these issues. This review is also crucial to prevent the erosion of trust in factual accuracy. We are entering an era where faith in the authenticity of facts is being eroded, propelling us towards a future where democratic values fade into obscurity under the weight of pervasive falsehoods.

We implore you to establish professional peer-review mechanisms for scrutinizing the research, publications, and opinion pieces produced by your faculty members who have called into question the values of human rights and international law. This entails subjecting the works of academics who have engaged in denying chemical weapons attacks in Syria to rigorous evaluation by experts in the field. The objective is to curb the proliferation of research that reinforces narratives divorced from truth; to safeguard academic freedom from being misused as a tool of violence and suppression against victims; and to prevent its exploitation as a façade for concealing war crimes and normalizing complicity in acts of genocide.

We acknowledge that history, fueled by collaborative efforts of champions of truth and justice — both among Syrians and global activists within and beyond academic spheres — will etch these crimes and the stories of tens of thousands of victims and hundreds of thousands of witnesses into the world’s collective memory.

Kind regards,

The «Do Not Suffocate Truth» campaign

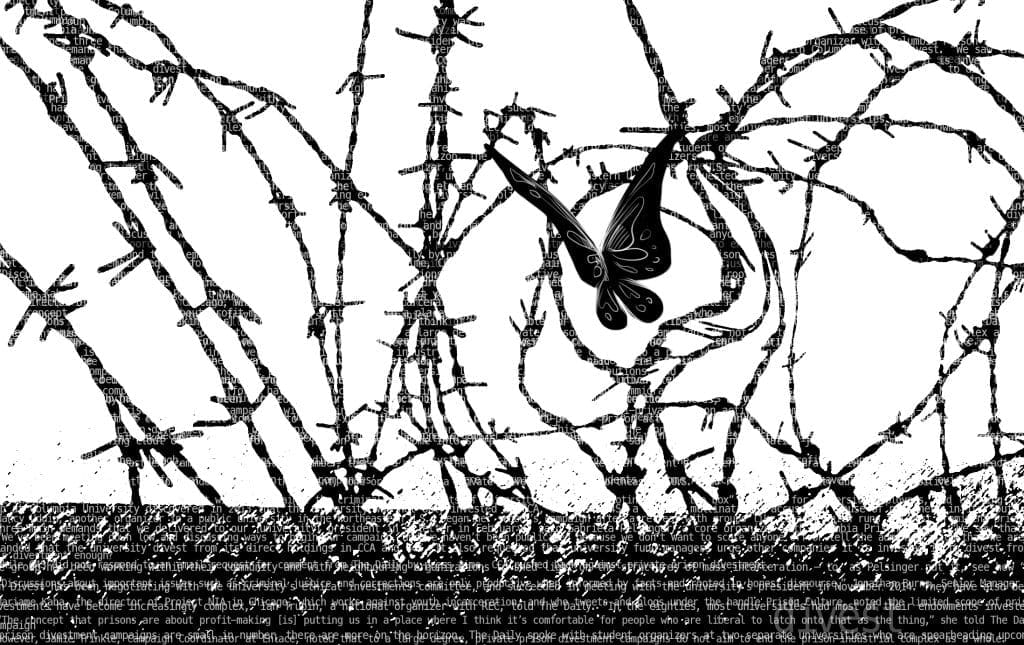

All images via Do Not Suffocate Truth