The Right to Bread and Social Justice

by Mai Shams El-Din for Mada Masr

26 April 2015 (part of a series of interviews by Mada Masr with human rights workers in Egypt)

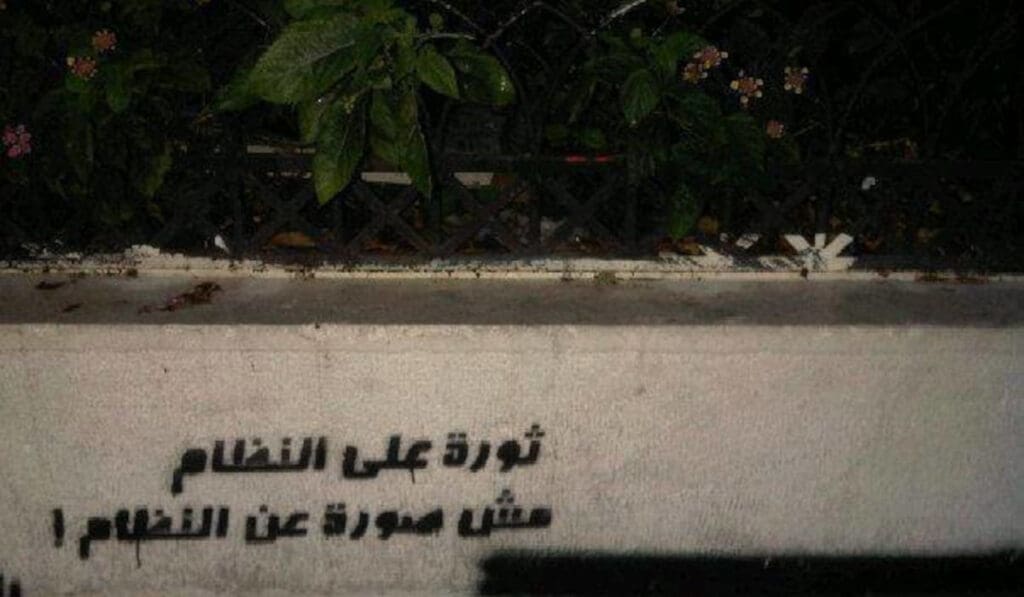

Chants for bread and social justice didn’t emerge out of the January 25, 2011 revolution. Long before 2011, a strong protest movement existed against the economic policies of former President Mubarak and his regime, which gained momentum in 2006 through the protests and strikes of labor workers in Mahalla al-Kubra.

Nadeem Mansour, director of the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights (ECESR), speaks to Mada Masr about the challenges facing the labor movement in Egypt and the battle for bread and social justice.

Mada Masr: Why do you think demands for social justice were masked by an identity battle post-January 25, 2011?

Nadeem Mansour: My work is still about the struggle for bread, social justice and the minimum wage, but after January 25, political organizations — the Muslim Brotherhood, Salafis and liberal groups — used the media to wage a very public battle over identity politics that masked this fight to some extent. Those who chanted for social rights in 2011 were not able to achieve their aims for numerous reasons — they didn’t have parties to speak for them, nor a media interested in propagating their ideals. Private media in Egypt is owned almost entirely by businessmen, who often have personal interests that are in conflict with labor movements.

At the ECESR, we have a monitor for economic and social protests. We’ve noticed that many protests over the last four years have had economic and social demands, and there have been a lot of them. In 2013, for example, the number of protests exceeded 5000.

Our role is to support these demands. Social justice is the key to making any real change, and to all of the problems facing Egyptian society today.

For example, terrorism will only be confronted and stability brought about by ensuring structural and social inequalities are addressed.

MM: How has the absence of political support for economic and social rights affected your work at the center?

Nadeem Mansour: Support of the poor and marginalized has never received much genuine political interest. Such attention fluctuates according to the political climate. Part of our role as an entity that offers legal, research and media services, and supports syndicates and local communities, is to help people find solutions to their problems on a local level, and then ensuring attention is given to their problems more widely.

Take the case of the minimum wage, as an example. Before we started the campaign and filed the lawsuit, the issue was not even a matter of discussion. The last minimum wage was set in 1982, as far as I remember, and it was around LE34. The campaign — both research and online — was initiated in partnership with workers, as there were no independent trade unions or syndicates at the time. We succeeded in raising the minimum wage from LE34 to LE400, and then to LE700 after the revolution. Now the minimum wage stands at LE1200, and we are still demanding its increase.

By setting the minimum wage as a revolutionary demand, it became a public issue, not just one concerning workers.

We are also interested in working more on specific cases, such as the issue of the Misr Shebin al-Kom Spinning and Weaving Company [the country’s largest textile company, based in Mahalla], which was sold to an Indian investor who already owned some of its competitors. He bought it illegally at a cheap price in order to destroy its equipment and decrease production and thus competition. This case prompted the government to issue a law protecting contracts, which we believe is unconstitutional and have challenged in court.

We partnered with a group of workers and farmers in 2012, when the constitution was being revised, to issue a document, “Workers and farmers write the constitution.” While the conflict over the civil or Islamic identity of the state continued, and there were many calls for workers and farmers to be educated about their rights, we decided to go and ask them about what they thought these rights should be.

We went to 22 governorates and we talked with thousands of people. We put them together in a legal document and ended up with something similar to the international Covenant on Economic and Social Rights in its relation to health, work and water.

This is part of our work, empowering local communities to make decisions that impact on their own lives.

MM: What about the syndicates and unions for workers?

Nadeem Mansour: The syndicates and unions are weak because they are part of a nascent movement that is also facing attacks from many directions, and lacks organizational capacity. Additionally, the strength of these organizations is closely related to that of local communities and their capacity to mobilize and sustain action.

The question is, can these problems be solved by uniform state action, or do they require a decentralized approach?

The economic and social crisis in Egypt is partly due to corruption and government bureaucracy. Attempts at reform often happen in a very centralized manner, whereas capacity building has to be conducted locally.

There are between 1500 and 3000 syndicates, and the union’s [Federation of Independent Trade Unions] capacity for representation is limited. Also, there is no legal framework to structure their work, meaning the right to strike is not protected.

The syndicates are weak right now, and consequently so is the union. The ability to mobilize in the public domain is difficult in Egypt currently, and the attention of the public is focused on political parties and activists. But the attack on syndicates is much fiercer.

MM: How would you describe this attack?

Nadeem Mansour: Workers face many problems, including: Dismissal, lack of financial rights, penalties against striking workers, threats, jail, physical assaults, torture and death — in extreme cases. The Protest Law also applies to workers, and is often enforced more vigorously. We have workers who are currently being tried for going on strike. Over the last 10 years, Egypt has developed a strong strike movement. The public mobilization on Jan 25 and June 30 were related to strikes over economic and social issues.

The entire movement is not often suppressed, as it is so vast, but smaller attacks are waged. During Morsi’s term in office, workers at the Portland Company in Alexandria were attacked by police dogs, and some were thrown from the second floor of the building, leading to severe injuries.

Just a few days ago, we were able to secure the release of a worker who criticized the administration of his employer on Facebook and is being investigated for it. Such attacks are often arbitrary, so we try to raise the profile of them in the media as much as we can.

Violence and the interference of the security services in the public domain have reached levels we haven’t witnessed in the last 10 years. The general climate is one of fear.

In one incident, a private company ended negotiations with its workers after military intelligence got involved. This is documented in the company’s official records.

MM: How do you deal with legislative obstacles to your work?

Nadeem Mansour: We have strong objections to the current law regulating the work of civil society and against various drafts of the newly proposed law. The state is attempting to restrict rights-based work without understanding this will hinder democratic reform.

The Center is registered according to the law. We are not an association, but a legal services company, providing consultancy on legal and economic matters. We are a legal office and as such pay the appropriate taxes and have the required documents. Our work is transparent and open.

We are, however, interested in the law governing non-governmental organizations, because we are interested in the ways people organize and in supporting this locally and nationally. We want a law that supports activities and solidarity work. If I’m a legal firm that wants to provide free services, I should be able to do so. Why am I being dealt with as an association in this case?

MM: When and why did you decide to work in human rights?

Nadeem Mansour: I began work as a trainee researcher at the Hisham Mubarak Law Center in 2008. I then started the ECESR with Khalid Ali and two other colleagues in 2009.

My interest in rights stems from my study of political economies, which focused on the relationship between the state, local communities and the labor movement. In human rights centers, there are many opportunities for young researchers to expand and develop their ideas.

Many people benefit from our legal services that wouldn’t have access to them otherwise. This motivates me to continue. Our work builds on that of many other generations and organizations. The public domain expanded dramatically after the revolution, enabling rights work to gain ground and the number of organizations dedicated to it to increase. The scale of such work was much more limited in the 90s, for example.

MM: Do you think the current restrictions on civil society will deter young people from getting involved in rights-based work?

Nadeem Mansour: I don’t think this will prevent new generations from joining. There have always been restrictions on rights-related work. Under Mubarak, and even before I started in the 90s and 2000s, we suffered consistent and fierce attacks. The intensity of the attack on the movement has also increased with its ability to make an impact.

As long as people’s rights are violated, there will be a need for such organizations to exist.

Mada Masr is an independent and progressive media outlet coming out of Cairo.