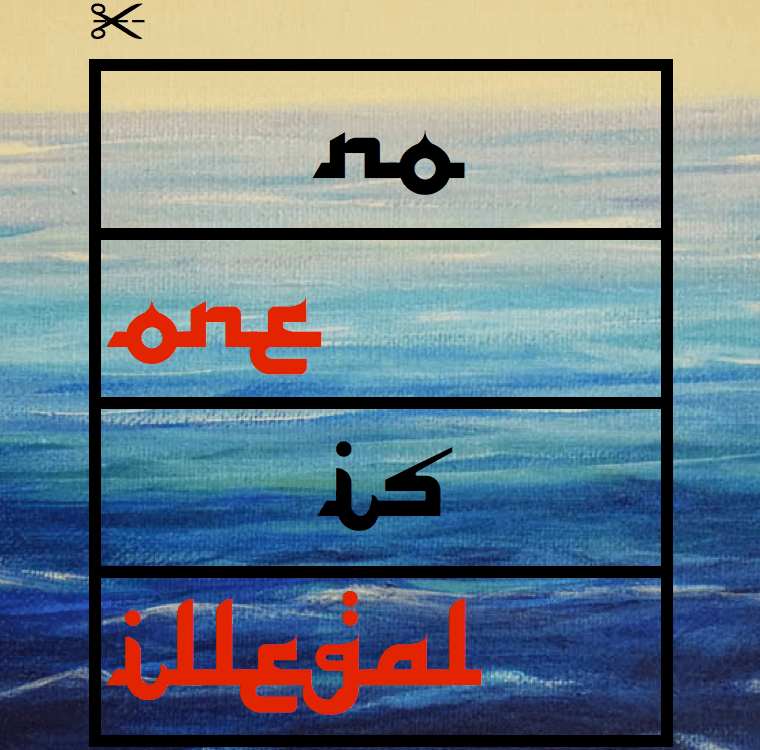

Refugees are Still Stuck and Stricken in Serbia

by Marc-Antoine Frébutte for his photography blog Migrations and Hopes

(original post)

Since the outset of the 21st century, one of the ways used by irregular migrants to enter Europe has been through the Balkans. The number of migrants taking this route has constantly fluctuated, depending on international events and opportunities, but it never exceeded a few thousand migrants each year, according to a 2015 Frontex report.i Since summer 2015, however, refugees fleeing conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan compounded existing migration levels and the number of people passing through the Balkans blew up. Until November 2015, Croatia—and further on Slovenia, Austria, and Germany—were accepting all refugees, regardless of their origins. However, because of the massive influx over the winter, new selection procedures were implemented, intended to reduce the number of refugees.

This has pushed those rejected into illegality and precarity, including within Serbia, where the research for this report was conducted. This included empirical research, participatory observation, informal discussions with non-SIA migrants, and structured interviews with NGO staff I met during my activities at the registration center in Preševo and in Miksalište Refugee Aid Center in Belgrade.

In the first part, I approach the initial context of the refugee crisis before focusing on how various selection procedures have changed over the course of the past few months. In the last part, I explain how those new selection procedures have caused dramatic situations for non-SIA migrants, who have been pushed into illegality, precarity and petty crimes, as well as excluded from the official routes and therefore trapped into smugglers’ networks.

Unprepared, uncoordinated and somewhat hostile: Governments scramble

About 900,000 refugees have transited through Serbia since the beginning of 2015. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), approximately fifty percent of these refugees were from Syria, twenty percent from Afghanistan and seven percent from Iraq. The remaining 23% were a mix of migrants and refugees who joined the flow, mainly from Morocco, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Somalia, and even some Balkan countries, such as Kosovo and Albania.ii

At the beginning of the crisis, nothing was set up to facilitate the transportation of refugees to Europe, leaving the transit to be performed off the cuff with what resources were available—by means of public or private transport companies, or through the many smuggling networks. Passing first through Hungary (which quickly closed its borders), the mass of travelers was redirected to Croatia and neighboring Slovenia in mid-October 2015. EU governments adapted slowly to the crisis around then, starting to coordinate the transportation of refugees.

In Serbia, transit was relatively fast by the early months of 2016, generally taking no more than two days. Immediately after their arrival on Serbian territory, travelers undergo registration procedures in the registration centers in Preševo (if they arrived from Macedonia) or Dimitrovgrad (if they arrived from Bulgaria). After registration, refugees then go by bus, train or taxi to the accommodation center of Šid, where they remain until the Croatian authorities accept them on their territory.

Feeling overwhelmed by the number of refugees, however, EU countries decided to react and limited access to only refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan (the so-called “SIA” refugees). In order to reduce the duration of asylum procedures and facilitate the return of rejected arrivals to their countries of origin, in October 2015 and again in January 2016 Germany and other European countries revised the list of countries considered “safe.” Countries such as Albania and Kosovo, and more recently the Maghreb countries, were newly added to the list.iii Since 18 November 2015, non-SIA migrants (not from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan) arriving in Greece are forbidden to continue to Europe and have only two options: request asylum in Greece or return to their country of origin.

No way forward, no way back for non-SIAs in Serbia

The implementation of new selection procedures was characterized early by mass deportations of non-SIAs at the Greek-Macedonian border. In reaction, protest movements appeared, with non-SIAs sewing their mouths shut in hunger strike, or confronting the police or Syrian refugees.iv The selection procedures were again made more strict, mixing registration document checks, fingerprinting, and language tests to discern non-SIA migrants who might try to pass themselves for refugees from SIA countries.

Despite the control procedures at the different borders, non-SIAs arrive regularly on Serbian territory and try to continue to Croatia and even Hungary. By leaving the “official” routes of transit established by the authorities of different countries, non-SIAs still manage to move through the borders thanks to smuggling networks and favorable mountainous territory in the Bulgarian and Macedonian border regions.

However, once in Serbia, non-SIAs are stranded. The border crossings to Hungary and Croatia are considerably more complicated. In the north, the Hungarian border has been fully fenced and is intensely monitored. In the west, the Croatian border is heavily controlled and the topography is no longer favorable for clandestine crossings, since the region is flat and almost devoid of vegetation where there might be cover from police patrols. Therefore, they must wait in Serbia for days, weeks or months before attempting the next border.

Once in Serbia, non-SIAs can register at the police station, where they must express their intention to seek asylum in the country. They receive a certificate of registration, on the basis of which the person has an obligation to report to a designated asylum center within 72 hours, during which they must either seek asylum in Serbia or leave the country. During those 72 hours, they can stay legally on Serbian territory and are entitled to certain rights: free movement within Serbian territory, free public transportation in Belgrade, and access to accommodation and food distribution in Krnjaca [a state-run camp on the outskirts of Belgrade].

If they do not leave the country or do not apply for asylum during this 72 hour period, though, they dive into illegality and no longer have that status which ensures them the minimum protection and assistance needed to survive in Serbia.v

In theory, non-SIAs have the opportunity to seek asylum in Serbia, since the EU has encouraged the Balkan countries to improve asylum policies as a prerequisite to accession to the EU and the liberalization of visa requirements for their nationals within the EU. However, this policy has had the effect of creating a buffer zone intended mainly to reduce irregular immigration into the EU. Although asylum procedures in Serbia and the Balkans exist, they are not fair and functional.vi Serbia can not accommodate as many refugees and migrants, as it does not have sufficient infrastructure, experience or financial means.

Furthermore, Serbian authorities know that refugees and non-SIAs do not want to stay in Serbia but go to Europe, which could explain their lack of commitment in devoting resources to ‘combating’ irregular migration as the EU would prefer. Serbia is only seen as a transitional passage for refugees, SIA and non-SIAs alike, so authorities issue certificates of registration and receive asylum requests with little fuss, knowing that applicants will try to leave the country as soon as possible.

Early figures for 2015, covering the months from January to August, confirm this analysis. Of the 103,000 people who reported intention to seek asylum in Serbia during that period, only 111 people actually made an application for asylum. Most of those seeking asylum in Serbia do not really want to stay in the country. If they are applying for asylum, it is often only because it allows them to get better conditions while they find a way to get to Europe. This reality enables Serbia to justify the lack of investment in improving the asylum system or providing more humane conditions for refugees. In fact, the situation would only get worse if transiting refugees would really decide to stay in Serbia.vii

Stranded, Criminalized, Marginalized, and Vulnerable

The introduction of new selection procedures has caused precarious situations for non-SIA migrants, pushing them deeper into illegality and precarity. Discriminated against and blocked, non-SIAs are left with three options for getting to their desired destination:

One could try obtaining a document under a false nationality (from a SIA country) and then going through the official transit circuit and over the various barriers, such as language and culture tests. To obtain a document issued under a Syrian, Iraqi or Afghan citizenship, they could either buy one from smugglers or lie about their identity during the registration process with police.

Or one might consider using smugglers’ networks to be accompanied through borders, avoid police patrols, and get connected to other networks to continue the journey afterward.

Or finally, some strike out on their own, attempting to cross borders by themselves. Equipped with GPS, non-SIAs walk through the borders, using mountains and forests where possible to hide from patrols, before following railroad tracks and bypassing police checkpoints.

The problem with the last two options is that non-SIAs, plunged into illegality and therefore especially vulnerable, are subject to pressure from local mafias. At Miksalište Refugee Aid Center, many non-SIAs (mostly Moroccans) who came without smugglers through Macedonia reported being attacked by armed gangs, robbed of their money and belongings, and, often, beaten on the legs, body and face.

Recourse to smugglers is not a guarantee of safety, either. Many non-SIAs have been abducted in Macedonia and sequestered by smugglers until their families pay for their release. Their illegal status makes them even more vulnerable and more likely to be victim of mafias since they do not have the option of lodging complaints and seeking protection from police and local authorities.

The journey through Bulgaria also has many risks. Afghans and Pakistanis traveling through this country regularly complain of police and mafia violence, dog attacks, abusive detentions, theft of money and personal belongings. Ana, an employee of Save the Children, told me:

“We receive a lot of teenagers traveling alone or in groups through Bulgaria before arriving in Serbia. Their testimonies are almost unanimous about the violence that they suffered in Bulgaria from the police and the mafia. For them, this is one of the most traumatic stages of their journey.”

After detentions ranging from several days to several months, they are either arbitrarily sent back to Turkey, or released and allowed to continue to Serbia. Just as in Macedonia, refugees in Bulgaria are victims of criminal gangs who exploit their vulnerability and their ignorance of the laws and the region to extort large sums of money. Vladimir, an employee of Praxis, an NGO working with refugees from Bulgaria, says:

“When they are not arrested and harassed by the police in Bulgaria, it is mafia groups that are robbing them and taking what they have. Taxi drivers also take advantage of the refugees’ not knowing the region, and charge them astronomical sums for short taxi journeys, like hundreds of euros for a short drive of a few kilometers.”

Where to sleep?

Once their 72-hour certificate of registration expires, non-SIAs in Belgrade face the problem of finding accommodation. Indeed, without valid authorization to remain on Serbian territory, it is impossible for them to stay not only in the refugee center in Krnjaca, but also in private apartments, hotels, or hostels, since they must be legally registered. Therefore, those who could not leave Serbia find themselves sleeping outside on the street, in abandoned houses, or near the train station.

They are limited by the law in their ability to find accommodation for the time they remain in Serbia. In effect, even if their finances would allow them to pay for accommodation, they are forced by legislation to stay in the street and remain in precarity.

To accommodate those in irregular situations without conducting mandatory registration procedures with the police, some hotel and apartment owners charge prices higher than those normally paid. For Amar, an Algerian blocked for three weeks and counting in Belgrade, it is

“hard to find a place in a hostel or a hotel if you are illegal. Either they do not accept us at all or they ask us to pay almost twice the normal price, and we have to leave the hostel at eight a.m. the next day. It’s this or the street! They take advantage of winter and of our illegality.”

Tensions among non-SIA communities

Tensions between the various non-SIA communities and nationalities are exacerbated by precarity, the inability to move towards Europe and the legislative blockage. The same groups are found daily in the same locations (NGO support centers, parks or around the station) and problems tend to multiply. Mirjana Ilic, a coordinator at Miksalište, describes this:

“Since borders are blocked, there are almost only non-SIAs who find themselves in Belgrade and in the center of Miksalište. Every day when they come to look for food and clothes, relations between Moroccans and Pakistanis are strained. It is not uncommon that verbal or physical confrontations erupt following an innocuous situation, thefts, or over the control of smuggling networks.”

Smugglers

Blocked in Serbia by the new selection procedures, non-SIAs do not have many alternatives after the expiration of their authorization to remain on Serbian territory: return to their native country, stay illegally in Serbia, cross the border by their own means, or resort to smugglers. Whatever their choice, the drastic selection measures are the delight of smugglers and networks, which have been able to resume their activities after having seen many months of decline while refugees, SIA and non-SIA alike, could still cross into the EU without restrictions. Non-SIAs are now dependent on smugglers again, especially as the Croatian and Hungarian borders are strictly controlled, offering few opportunities to cross on foot since vegetation and terrain do not provide cover from police patrols.

As explained by Jelena Hrnjak from the NGO Atina, smuggling networks were established in Serbia more than twenty years ago, emerging around villages whose populations had earned money from contraband during the time of Yugoslavia and already knew the paths across the borders to avoid police controls. They have slowly begun specializing in illegal border crossings for irregular migrants. Their activities have had peaks both during summer 2015 with the onset of the crisis and now again with the implementation of new selection procedures.

“Nowadays [February 2016], smugglers propose to cross from Greece to Macedonia for a hundred euros,” Jelena says. “From Macedonia to Serbia, they ask €350 to cross the border, before connecting them with a taxi service that will drive them directly to Belgrade for €300.” To cross from Serbia into Croatia, Hungary, or Austria, it costs between €500 and €1,500, depending on destination and contacts. Since the beginning of 2016, prices have increased as the number of non-SIAs has exploded.

For Syed, an Indian returned to Serbia twice in one month already:

“Borders are very hard to cross alone. I tried twice, once into Croatia and once into Hungary, but each time I was deported back to Serbia. One month ago [December 2015], smugglers asked €350 to go to Hungary, but nowadays with the number of people stranded, prices rose and you have to give almost €1,400. To pay for the crossing, you give the sum to a third trustworthy person who will give it to the smuggler when you call him to say you arrived in Hungary. Sometimes the person in whom you had confidence fled with the money, and if you did not manage to pass the border, you have lost everything.”

Furthermore, arrangements with smugglers are not necessarily a guarantee of success even if they “succeed.” Once the border is crossed and the smuggler’s job complete, non-SIAs are left to their own devices in unfamiliar areas where they can be confronted by police or legal issues. Amar said,

“My friend paid more than a thousand euros to smugglers to take him to Hungary. Once in Budapest, he was arrested by police and sent to the court. He was sentenced to six months in prison for illegal border crossing and he is not sure that he will be able to stay in the country after he has served his sentence.”

Taxis are also beneficiaries of these new selection procedures, as they can take advantage of non-SIAs’ illegality to increase the prices of taxi rides. For many non-SIAs I met in Belgrade, transportation from the Macedonian and Bulgarian borders to Belgrade was done by taxi. Taxis are popular not only because they are quicker and more discreet, but because it is the only solution available to reach Belgrade: in fact, it is forbidden for non-SIAs to take public transportation or buy a bus or train ticket before registering with the police, and non-SIAs normally register in Belgrade since they are afraid to be returned to Macedonia or Bulgaria if they register in Preševo or Dimitrovgrad.

Security Risks

Taking advantage of non-SIAs’ illegality, mafias and smuggling networks promise them accommodation and easy passage through borders. However, travelers have often reported getting kidnapped and held in an apartment in Belgrade until their families pay for their release. Afraid of being deported by the authorities, victims of kidnapping do not dare to complain to the police, in which they have limited confidence anyway. This situation favors mafia organizations, who feel emboldened by the atmosphere of impunity created by the inaction of authorities and the fear of non-SIAs to lodge complaints.

Sexual Abuse

Not very well-documented, sexual abuse towards refugees is a reality. Jelena Hrnjak from Atina explains:

“Sexual abuse on refugees often goes unnoticed. You hear about it when it is linked to another case, as with the brother of two migrant girls who was stabbed while trying to protect them. If he had not been killed, nobody would have heard of the case. When women are traveling alone or do not have money to continue with smugglers, sexual abuse or prostitution can become a way to ‘pay’ for their passage.”

Among stranded non-SIAs in particular, sexual abuse has been less of a topic as they are almost exclusively men. However, now and in the coming months the problem should be considered, especially as more refugees, including women, are being returned from the European Union and are being stranded in Serbia as well. As of 1 March 2016, selection procedures became even more drastic, as borders were slowly closed entirely, even to refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Intimidation of NGO Staff

Threats from taxi drivers and smuggling networks on employees or volunteers from NGOs also represent a collateral damage the new selection procedures have made. The increase in abuses against refugees has been accompanied by an increase of pressure on NGOs. They are considered to be an obstacle to taxis’ and smuggling networks’ business. NGO staffers are sometimes intimidated during their work, in order to discourage their involvement with refugees and to limit what information they share.

At the Serbian-Macedonian border, taxi drivers do not hesitate to intimidate NGO staffers helping refugees on the road connecting Tabanovce to Miratovac. To avoid problems and tensions with taxi drivers, NGO staffers reported that they do not get involved with refugees in this area, but try to give them information and advice at the crossing point between Macedonia and Serbia. In Belgrade, NGO employees working near the train station also report that they have been intimidated by taxi drivers and individuals who tell them not to inform refugees as it would impact their “business.”

NGOs as the main source of support for basic needs

As a result of the combination of closed borders, illegality, and the theft and violence perpetrated by mafias, many non-SIAs find themselves blocked in Belgrade without any financial means, neither to continue their journey with smugglers nor to provide for themselves during the time they remain in Serbia. Therefore, they are forced to rely on various legal or illegal ways to survive in Belgrade.

Fortunately, many independent NGOs are organized to distribute clothes, food, information on asylum in Serbia and on the legal aspects of crossing the Croatian border or returning to their native country. Some NGOs help travelers financially, by buying bus or train tickets to the Croatian border. Other associations offer a place to sleep to non-SIAs. Those whose territory authorization has expired and cannot access the refugee center of Krnjaca can stay a few nights in the accommodations offered by NGOs (albeit limited in the time they can stay, because many non-SIAs are facing the same situation).

While NGO donations help cover basic needs (food and clothing), they cannot help deprived non-SIAs to any wider extent. Unable to work in Serbia, either legally or illegally, many non-SIAs have other stratagems to try to earn money, either in order to improve their living conditions (with cigarettes, diversified food, or accommodation) or to pay smugglers to cross into Europe. For non-SIAs, one of the most abundant and accessible resources are the goods distributed by NGOs. Every day, they get provided by multiple NGOs, creating a surplus of donations they can resell to local people. Mirjana Ilic, coordinator at Miksalište, explains:

“Some come every day, sometimes several times a day, to try to get new clothes and new shoes. They immediately go to sell it for almost nothing to some Serbian people, a few hundred meters from here. Later, we find in local markets or in flea markets the same goods we gave them earlier. It’s the same for food. They sort what they eat and what they sell. It’s problematic because our resources are not limitless and other refugees who are truly in need are penalized as we do not have reserves to distribute. We try to reduce theft, but it is hard to define who has already received goods or not.”

When they do not have access to goods distributed by NGOs, some steal from other refugees, usually at night when they are asleep either near the train station or in accommodation centers. Mirjana Ilic continues:

“At Miksalište, we often see refugees who have had their jackets or their shoes stolen overnight. In the center, it is not uncommon that some refugees steal mobile phones or backpacks from other refugees. Sometimes they also steal from the volunteers. One can understand this gesture, seeing their situation, but it is very detrimental to NGOs with limited resources and for refugees for whom a mobile phone is often essential to continue to Europe and to maintain contact with their families.”

There’s just no money

Wary of theft, some refugees travel only with small sums of money on them. This practice seems widespread among Afghans and Pakistanis as they go through Iran and Turkey, two countries known for police violence and robbery toward refugees. At each step, their families send them money via transfer to continue their travel. They are dependent on access to companies like Western Union to receive money sent by their relatives.

However, in Serbia, only those legally registered can withdraw money in transfer agencies. Most non-SIAs who are blocked in Belgrade can not receive money from their families via transfer as they are in an irregular situation in Serbia. For them, the only way to receive money is if a second person is willing to give his name on their behalf and withdraw the money with his passport in transfer agencies. Tariq, a Pakistani asylum seeker, explains:

“I made an application for asylum in Serbia and I expect an answer soon. Meanwhile, I cannot withdraw the €300 that my family sends me every month through Western Union, because I have no legal status here in Serbia. I approach Serbian people or refugees who have already received asylum in Serbia and who can legally receive money. If no one will do it for free, I have to offer them ten or twenty percent of the money I get from my family to lend me their names. It’s the only way I have to get this money and live a little better here.”

Working for smugglers and taxi drivers

For many refugees and non-SIAs without financial resources, a way to finance the continuation of their travel is to work with taxi drivers and smugglers’ networks. Between Tabanovce and Miratovac, at the Serbian-Macedonian border, refugees have to walk many kilometers before reaching the shuttles that drive them to Preševo. On this road, people working for taxi drivers try to convince refugees to take a taxi to the registration center at Preševo or even directly to Šid.

All along the road to Germany, the smuggling networks that have developed also rely on refugees and non-SIAs themselves to act as mediators with other refugees. Linguistically and culturally similar, it is easier for them to convince members of their communities to resort to the various services offered by smuggling networks. In Belgrade, they can work on behalf of a network of smugglers, acting as an intermediary to other non-SIAs blocked in Serbia.

Albert Grain, an administrator at Miksalište, explains:

“Smugglers use refugees and non-SIAs with financial problems to hook potential customers in Miksalište, or in parks near the bus station. Working as intermediaries, they can earn quick money because they get a commission on each person going with the smugglers. When they earn enough money, they can pay smugglers themselves to get driven through the borders. At Miksalište center, we kick them out, but they continue to operate near the train station. Smugglers are also found in the so-called “Afghani Park” and in cafés near the train station where they meet those who want to cross to Europe.”

Harm Reduction Measures

After the implementation of new selection procedures at the borders of the EU, conditions for non-SIAs in Serbia worsened, strengthening their marginalization and exclusion from official channels and pushing them more deeply into illegality. This phenomenon is not about to stop, as EU countries continue to clench up, gradually reestablishing Schengen border controls and tightening national regulations on obtaining asylum. In addition, selections and language tests have gotten more drastic and efficient, significantly reducing official border crossings.

Unless alternative responses to the flow of refugees are taken at the European and Serbian levels, it is likely that the situation in Serbia will worsen in the coming months. Once the weather conditions to cross the Mediterranean are more favorable, more migrants will find themselves stranded in Belgrade, unable to go further. Therefore, in order not to let the conditions of migrants degrade indefinitely, and to reduce the abuses generated by this situation, some realistic adjustments should be considered.

[AntiNote: We, along with the author, grudgingly take for granted here that the most urgently necessary “adjustments”—in other words the lifting of arbitrary and discriminatory selection restrictions and the opening of borders—are highly unlikely to be made by European national and international authorities. Barring significant public pressure. So prove us wrong. No, really.

Until then, back to Marc. Sorry to interrupt.]

Extending the duration of authorization on Serbian territory for non-SIAs or creating a special registration document which would permit refugees to legally receive money via transfer and to pay for accommodation would be a great improvement, since many could afford accommodation but are blocked by legislation. Moreover, since the refugee center in Krnjaca is not fully occupied, it would be wise to leave it open and accessible.

It also appears that many non-SIAs would be willing to return to their native country instead of remaining blocked in Serbia, but they cannot afford the price of a flight back. Some report that they are hoping to reach Slovenia, where they would have the possibility to go back home for free on a voluntary basis. Finding an agreement with the EU to finance voluntary returns would be of interest for both Serbia and the EU as it would reduce the number of migrants blocked in Serbia.

Furthermore, many of those who find themselves blocked in Belgrade are unemployed, unoccupied and bored, increasing tensions and feelings of worthlessness. It would be constructive to better incorporate refugees stranded in Belgrade into NGOs’ activities. Giving them a chance to be active and to participate in NGO activities would be an opportunity to get them involved in a community and to reduce tensions linked to boredom.

However, these measures would be of limited benefit if the number of refugees blocked in Serbia significantly increases in the coming months, since the country is absolutely not ready for such a migration influx. In the meantime, fighting and reducing impunity for smuggling networks should appear as a priority for Serbian authorities if they wish to avoid an escalating trend of precarity and criminality on their territory.

All images: Marc-Antoine Frébutte

Notes

i. FRONTEX (2015), Western Balkans Quarterly Report, July-September 2015, http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/WB_Q3_2015.pdf

ii. IOM (2015), Report on European Migration Crisis (Western Balkans), https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/situation_reports/file/European-Migration-Crisis-Western-Balkans-Situation-Report-11Sep2015.pdf

iii. Le Soir (2016), Migrants: Berlin va placer l’Algérie, le Maroc et la Tunisie sur la liste des «pays sûrs», http://www.lesoir.be/1106333/article/actualite/fil-info/fil-info-monde/2016-01-28/migrants-berlin-va-placer-l-algerie-maroc-et-tunisie-sur-liste-des-

iv. L’Express (2015), Bloqués à la frontière de la Macédoine, des migrants se cousent la bouche, http://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/monde/europe/bloques-a-la-frontiere-de-la-macedoine-des-migrants-se-cousent-la-bouche_1738696.html

v. Article 22, § 2 of the Asylum Act of Serbia

vi. Feijen, L. (2008a) “Facing the Asylum-Enlargement Nexus: the Establishment of Asylum Systems in the Western Balkans”, International Journal of Refugee Law, 20 (3): 413-431.

vii. Belgrade Center for Human Rights (2015) Right to Asylum in the Republic of Serbia 2014, Belgrade, http://www.bgcentar.org.rs/bgcentar/eng-lat/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Right-to-Asylum-in-the-Republic-of-Serbia-2014.pdf (accessed 17 September 2015).