Transcribed from the 10 September 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the entire interview:

Eventually we will prevail. We must prevail. Because this is an injustice that is too evil to go on. But it is absolutely going to take each and every one of us to join in this fight.

Chuck Mertz: Slavery still exists in the United States. In fact, it’s thriving in US prisons. But something is being done about it. Here to tell us about the September 9th national prison strike, live from Austin, Azzurra Crispino is the media co-chair for the Industrial Workers of the World’s Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Azzurra.

Azzurra Crispino: Thank you.

CM: The Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee’s website states, “People are organizing across the United States and the world in order to stand in the streets in solidarity with those locked behind bars who will strike on September 9th against prison slavery.”

Let’s start with that term. What is meant by “prison slavery”? When we talk to, for instance, a sweatshop activist, they’ll say, “These people are living in slave-like conditions.” Or we’ll hear something is “akin to slavery.” Because when people think of slavery, they think of the lithographs that we see from the Civil War series on PBS.

So what is meant by “prison slavery”?

AC: Although we think of the Thirteenth Amendment as abolishing slavery, it didn’t. The Thirteenth Amendment states that conscripted labor is still legal if it is a punishment for a crime. And since you referred to those lithographs: some of those images are still happening in the United States today. There are prisoners who work in the fields with overseers on horses with long rifles. There are folks who are working in the manufacturing sector, or who are raising cattle, and these workers, more often than not, are not paid at all.

CM: So prison slavery is protected by the constitution? Is the only way, then, to reform it by amending the Thirteenth Amendment?

AC: That has been one of the calls that has come out of this strike (which by the way only began yesterday, but it is not a one day action. I want to make that clear to your listeners). In Texas, Malik Washington (one of the architects of the prison strikes that happened in April) and many other activists behind bars have been calling for an “Amend the Thirteenth” movement, saying that we need another constitutional amendment which would just end slavery, period.

CM: So why do you think people see this system as fair? How difficult is it for you as an activist to get sympathy, to get empathy, to get affinity groups to back up people who are incarcerated?

AC: The fact that it’s a punishment for a crime leads people to believe that this is a just system. We have this idea that if you did something wrong, you ought to be punished. That is the myth that needs to be shattered. Realistically, most of us commit crimes every day, and those of us who have white privilege don’t end up incarcerated for them. There is a certain racism involved.

The way to build empathy with people is first to create connections among groups of people who don’t have family or friends incarcerated, and to get them to have a relationship with a prisoner. That’s part of why the other organization that I work with, Prison Abolition Prisoner Solidarity, pushes for pen pals to prisoners programs. When you get to know a prisoner, you no longer think of prisoners as a monolithic group. You begin to see individuals, and you begin to see past this idea that we should judge people on the basis of the worst thing that they’ve done, but instead to think of the person as a whole.

The second part is to recognize that telling someone that they have done wrong is not a good way to get them to change their behavior. What we need to do instead is to model right behavior and show people how to do what’s right. In order to do that we need to abandon a system of punishment and we need to switch to a system of rehabilitation.

CM: To switch from punishment to rehabilitation is the bigger goal—how likely do you think that is? What do you think is the likelihood of us shifting back to rehabilitation, when it is perceived, at best, as a failed policy of the 1970s?

AC: Let me be clear that when I say “shifting to rehabilitation,” I don’t mean creating rehabilitative programs inside of prisons. I mean completely dismantling prisons, period, which means implementing systems of restorative justice, transformative justice, community-based programs, drug rehab, etcetera. Dismantling of the prison industrial complex is going to take all of society becoming involved in the effort.

The barrier isn’t so much the “common people and their lack of empathy” as much as it is—to borrow from the Occupy movement—the one percent and the people who make tremendous amounts of profit from the prison industrial complex as it stands today. Until we’re able to wrest power back from those folks, and put it into the hands of the community, we’re not going to see that solution.

But what we’re starting to realize is that if you and I have a conflict—let’s say that we’re at a bar and you take a swing at me. What currently happens is: the police get called, and the state takes over the conflict. If we were to go to court, it wouldn’t be me versus you, it would be the state versus you. Then that conflict is no longer mine, and I can’t learn or grow from it. And we incarcerate you, but that doesn’t necessarily heal me from the trauma or make me feel safer. It just shifts who is likely to be your next victim.

What we want to see are systems of restorative justice where the victim and the perpetrator of the action can come to understand the societal pressures around what happened, and come to a resolution among themselves, whether that’s talking circles or some other alternative form; this may vary on a case to case basis. But more and more, we are recognizing that the current system only harms everybody.

CM: How much do you think that punishment policy is driven not by what might be best when it comes to justice, or what might be best when it comes to this or that inmate, or what might be best when it comes to society—but rather is driven by the desire for profits produced by prison slavery?

AC: Completely. We could look at cases that have become really commonplace for the mainstream media to discuss, for example Brock Turner: he engages in a sexual assault that we can all agree was egregious and beyond the pale. What did he get? Three months in county jail—and in protective custody, may I add. That is compared to—just to pick an example at random—Chicago native Jeremy Hammond getting sentenced to ten years for nonviolent hacking done on behalf of the Occupy movement and the resistance movement worldwide. If we’re concerned with harm to the community, these sentences don’t make any sense.

If we recognize what’s going on is a profit motive, then we realize that Jeremy Hammond’s actions cost corporations and the powers that be a great deal of money and a lot of embarrassment, whereas what Brock Turner did—well, that just hurt a woman, who cares?

As a community, that is not how we should be looking at these crimes. But as long as we have a system of so-called justice that is really only meant to push a profit motive of the few, those are exactly the kinds of sentences that we’re going to continue to see.

If we are trying to get workers fifteen dollars an hour, and they are competing against prisoners getting paid fourteen cents an hour—or not at all—it’s clear, it’s going to be impossible.

CM: When it comes to the prison industrial complex, how much worse has prison slavery become under a more privatized prison system—the kind of privatized prison system that now president Obama says he is backing off from, even though the number of prisoners that will be affected by his policy are very few?

AC: Right, I think it’s thirteen federal prisons, and it’s going to take some time to phase them out. The private-public distinction is worth keeping in mind, but it’s also worth keeping in mind that corporations are all over the pie of public prisons too. Public prisons are sometimes publicly traded in stocks; some engage in practices like convict leasing, having prisoners work from behind bars for private corporations, even in public prisons.

There are reasons we’re an explicitly abolitionist movement and not concerned with reforms that don’t lead to abolition. Let me just tell you a story. One of the prisoners who I support is a Chicano anarchist named Xinachtli Alvaro Luna Hernandez. In 1978 he was part of the prison strikes at Ellis Unit which ended up leading to the Ruiz v. Estelle Supreme Court decision [ruling correctional conditions and practices in Texas unconstitutional]. He’s been incarcerated on and off since then; he did eight years on death row following his involvement in the 1978 strikes.

I asked him once how much things have changed over the years (he has spent more than my lifetime incarcerated). He said, “Well, it’s a different shade of lipstick, and it’s slightly younger pig, but nothing’s really changed. The types of brutality that I saw in the seventies, I’m still seeing today.”

There are now a greater number of prisoners being held in administrative segregation or in long-term solitary confinement, and—in certain cases—in even more repressive conditions. So from the perspective of becoming more humane or more rehabilitative or more fair, there hasn’t been any improvement in the 45 years since Attica, whether we’re talking about private prisons or publicly-run ones.

CM: Your group, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, released this statement: “On 9 September 1971 prisoners took over and shut down Attica, New York State’s most notorious prison. On 9 September 2016 we will begin an action to shut down prisons all across this country. We will not only demand the end to prison slavery, we will end it ourselves by ceasing to be slaves.”

Why mark the anniversary of Attica? After all, that was part of what was then being called the Prisoners Rights Movement, but as you were just saying, not much has really changed over the last 45 years. So why focus on the anniversary of Attica if the protest movement for prisoners’ rights hasn’t proceeded in a positive fashion?

AC: I think the movement has proceeded in a positive fashion. That can still be true even if conditions haven’t improved. The fact that so many people on the outside are involved in this movement is a difference from 45 years ago. There were over fifty cities that engaged in protest actions in solidarity with the kickoff of the September 9th strikes. I wasn’t alive during Attica, but my sense is that that uprising didn’t have as much popular support as this strike action is having today.

But it’s important to remember that in the hearts of prisoners, the Attica uprising is a golden moment of mythology. The murder of George Jackson was really seen as an atrocity. He had been calling for a prison labor union. He had been calling for a nationwide prisoners strike. When he was gunned down, people were completely heartbroken, and the Attica prisoners decided to rise up in rebellion, in solidarity, and take autonomy over their own lives in response.

The other thing that bears remembering is that these are people who ultimately ended up not just being gunned down, but stripped naked and made to run through a gauntlet by the National Guard, urinated upon, and tortured for their willingness to risk everything to stand up against these cruel conditions. And yet there has not been a single prosecution of any law enforcement or National Guard who were brought in specifically to engage in these actions. We know that every single person who died during those four days of rebellion did not die at the hand of prisoners, but at the hands of the state.

Those details have remained in the consciousness of prisoners, so people are hearkening back to that as a way of saying, “Look, our situation is the same as it was 45 years ago, and we are going to take this date, this very important anniversary, as a way to kick off this strike and shed light.”

Perhaps at a somewhat more tactical level, there had been calls for strikes in April and there have been work stoppages happening on a rolling basis throughout the summer, so the decision was made that we needed a national strike to begin in the fall. And at that point, the September 9th date was the most obvious. But there is also a mythological air to the Attica uprising.

CM: There have been actions taking place nearly every day in August and September leading up to the protests that began yesterday. There have been actions in Philadelphia; Atlanta; Durham, North Carolina; Austin and Houston, Texas; Kansas City, Missouri. Posters, graffiti, and banners opposing prison slavery have been seen in Portland, Oregon; New Orleans; Indianapolis; Minneapolis; Athens, Georgia; Denver, Colorado; Oakland, California. Pro-strike graffiti for your organization, the IWOC, has been found in rural Indiana.

This action seems to be touching a wide demographic—rural, urban, seemingly affecting all races. So what happened yesterday, and what kind of affinity, what kinds of organizers, other actions, and other activists did you see helping in your protest against prison slavery?

AC: Let’s begin with the outside actions. To do a quick roundup, my absolute favorite came out of Portland, Oregon. They protested at an AT&T store, because AT&T uses call center labor that is prison labor. Then they had a Ronald McDonald and a fake prison—holding workers—outside of a McDonald’s. Then they shut down a highway, and then they did a noise demonstration at a local jail. And there were folks who had just gotten out of jail who immediately walked up and joined in the demonstration. That was a particularly effective and beautiful action.

We did have a few arrests: three in Atlanta, Georgia, and three in Nashville, Tennessee, outside of the CCA corporate offices. But we have also seen international solidarity. Greece had an action standing in solidarity with our strikes outside of a women’s jail, and I believe there are workers striking inside of prisons in Greece as well. We have had actions at US embassies: two in Australia, one in Sweden, and a few elsewhere around the world. And we haven’t done the full tally of actions that have come in.

It’s been a wide gamut of actions occurring outside of prisons. Obviously, those are easier for us to hear about, because we get immediate response and feedback from them. But it should also be mentioned that we’ve already had reports of several units that have had work stoppages. We know that Holman, in Alabama, did go on strike. That’s the home of Melvin Ray and Kinetik [Robert Earl Council, Jr.], both of whom have been major organizers behind the Free Alabama movement, who were the folks who originally called for a work stoppage and are the reason IWOC came into existence. They were the ones who reached out to the IWW, and said, “We want to unionize, and no other union will help us. Will you?” And we said, “Of course.” They have been a major force.

When our constitution was written, there was an understanding that there would always be revolt and rebellion, and that we would rewrite the constitution often. We have not held to that intent of the founding fathers. The constitution is a document that needs to be burned and replaced with something completely different.

In Bonifay, Florida, there have been sit-down strikes and work stoppages at Holmes prison. Elsewhere in Florida there have also been reports of riots at Gulf and Mayo prisons as well as smaller disturbances at a few other institutions. We know that Fluvanna prison, which is a women’s unit in Troy, Virginia, definitely participated in the strike. In North Carolina we have reports of prisoners who refused to work, though they’re not naming their unit. Chelsea Manning kicked off a hunger strike in Leavenworth, Kansas, on September 9th. And in Chowchilla, California, we heard that work strikes and lockdowns were happening at the Central California women’s prison. In Kansas, once again, we have reports of women prisoners who are striking; they are keeping the name of that facility unknown at this time for their own protection. And in Tecumseh, Nebraska, we have reports of some guards that were attacked, we believe in relation to the strike, though that has not yet been confirmed.

If we consider that the strike is barely 24 hours old, the fact that we’ve already had these reports—in Florida they are saying that in one unit, 400 prisoners went on strike—I expect that within the next week we will hear about strike actions that occurred in at least 24 if not over half of the states in the United States. And we’re still hearing about solidarity actions abroad that are showing up online. I just got reports this morning that my home town of Naples, Italy, had an action in solidarity with one of their political prisoners and also standing in solidarity with all political prisoners. I asked them if they think that all prisoners are political prisoners, and they said, “Yes: all prisoners are prisoners because of political conditions, so we absolutely stand in solidarity with the prisoners’ strike in the United States.”

CM: Your group says that “prisoners are on the front lines of wage slavery and forced slave labor, where a refusal to work while in prison results in inhumane retaliation, and participating in slave labor contributes to the mechanisms of exploitation.”

How does prison slave labor in the US contribute to the overall global mechanism of exploitation? Does prison slave labor have an impact on those outside of prison?

AC: Absolutely. We have received a lot of solidarity from different unions in the manufacturing sector and carpenters’ unions, because they recognize there is no way for them to compete against slavery prison labor. The Fight for Fifteen campaign, for example, has been a large source of solidarity. If we are trying to get workers fifteen dollars an hour, and they are competing against prisoners getting paid fourteen cents an hour—or not at all—it’s clear, it’s going to be impossible.

And there may be conscientious consumers who refuse to buy anything that is not labeled Made in the USA. Say they go to Victoria’s Secret and buy a bra. It turns out that there are prisoners in the United States being forced to remove labels that say Made in Honduras and replace them with Made in USA labels. The only thing about that bra that is made in the United States is the label, and that that is being made by a prisoner held under slavery conditions.

CM: Do you think prison slavery is Too Big To Fail? That is, are major corporations so dependent on this revenue stream that they will simply do everything they can to keep prison slavery in place?

AC: The resistance against us, of course, is going to be great, and that’s why we need absolutely everybody to join in the fight. But I believe, to quote Martin Luther King, that the arc of history is long but bends towards justice. Eventually we will prevail. We must prevail. Because this is an injustice that is too evil to go on. But it is absolutely going to take each and every one of us to join in this fight.

My day job is as an associate professor at the local community college. I’ve never been incarcerated. Why did I join up in this fight? Because I started writing to prisoners. And from my communication with them, I realized I’ve been sitting in this place of privilege and not even realizing the way this system impacts the lives of my brothers and sisters, and members of my community.

But since we started doing things like solitary confinement demonstrations on the street, the response has been overwhelming. There is always somebody who walks by and will stand and stare at a re-created solitary confinement cell, and then look at us and say, “Yeah, I did time in solitary confinement.” And when I tell people that I write to prisoners, so many tell me they have a brother who is incarcerated, or a daughter who is incarcerated. Yesterday at the grocery store I was taking a call, a media request for IWOC, and a woman overheard me and told me afterward that her daughter is in jail, and she’s distraught and doesn’t know what to do.

As we begin to talk about this problem, we realize that it touches all of our lives, at the very least because most prisoners will eventually come out; they will return to our communities, and they will be worse for the wear. Many of them are going to come back with post-traumatic stress disorder, and whatever problem they had that led them to go to prison in the first place—the likelihood that it’s going to have been made better by their confinement is slim. This is a problem that impacts all of our communities.

Are the powers that be just going to give up and say, “Oh, sure! Let’s end the War on Drugs and let’s switch all of this money to go into rehabs instead. Let’s have drug policies that make sense.” No. Not unless we make them. So we must make them. That’s going to take each and every one of us engaging in daily actions of resistance.

We need repression response. When prisoners are being repressed for their strike actions, you can call in and write letters as a way of showing solidarity. That’s really the only protection that we can give to our striking workers. Also, writing postcards to a prisoner shows directly to guards that these prisoners have outside contact, which helps to keep them safe. But it’s also a lifeline for prisoners, and it is a direct action that will absolutely make a difference in somebody’s life.

If I can tell a quick story: I had a guy who had written in the past, and it took me forever to write him back, and I was feeling really guilty about it, but I eventually managed to write him a quick postcard. I got a letter back from him telling me that my postcard reached him on his birthday, and that I was the only person who wrote him on his birthday, and he hadn’t had any mail in a year, and how much of a difference it made that someone reached out to him and wrote to him on his birthday. So I just encourage each and every one of you to make a similar difference in somebody’s life.

CM: Azzurra, one last question for you, and as it is with all of our guests it’s the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

What does it say to you about the United States—and, in particular, democracy in the United States—when our constitution allows for prisoners to be treated as slave labor?

AC: That’s a particularly tough question for me to answer. I’m an immigrant to this country. I raised my hand and swore to uphold the US constitution when I became a US citizen, and I came to this country believing in the promise of freedom.

But when our constitution was written, there was an understanding that we would have revolt and rebellion, and that we would rewrite the constitution often. We have not held to that intent of the founding fathers. This is a document that, at this point, needs to be burned, and it needs to be replaced with something completely different.

I believe in horizontal decision making, modified consensus, and cooperative action. Ultimately I want to see us replace our current system of a representative republic—we don’t have a democracy—with a truly democratic system. The front line of that fight is standing in solidarity with prisoners.

CM: Azzurra, I really appreciate you being on the show this week.

AC: Thank you so much, it was a pleasure.

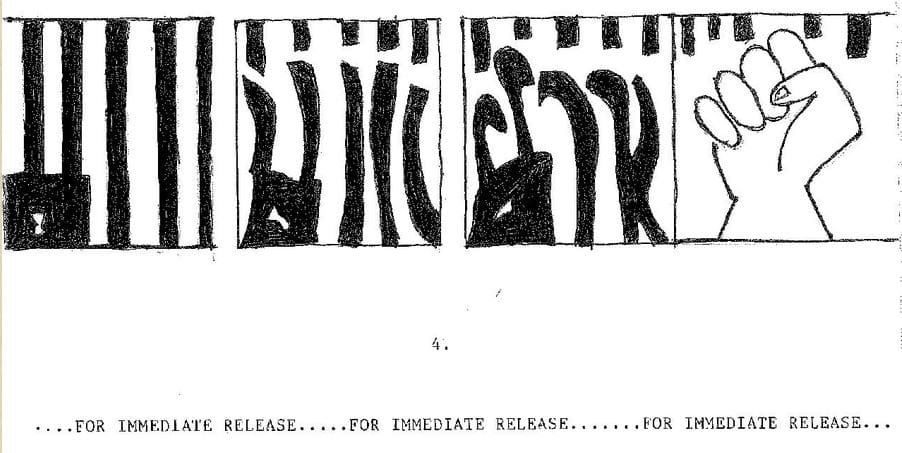

Featured image: drawing by Xinachtli included in his 1 September 2016 press release on the then upcoming Attica anniversary prison strikes. Read this and other communiqués here.