Transcribed from the 9 July 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

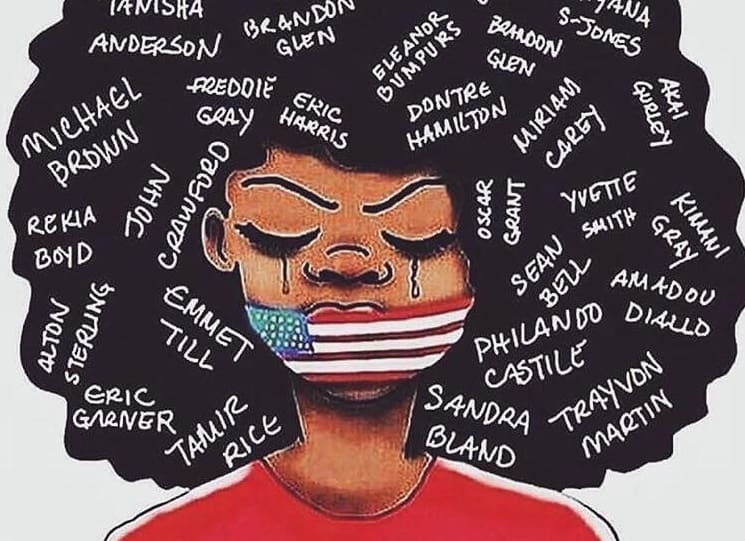

We have to understand the violence of “broken windows” policing within a long continuum of ongoing, foundational, colonial, imperial, racist violence that produces the US political economy. Black Lives Matter didn’t actually arise from police killings. It was first a response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin—a vigilante-style killing. We have to understand the totality of this violence.

Chuck Mertz: What if I told you that at the heart of the policing crisis we are facing today is—you guessed it—neoliberalism? Here to describe the deep reasons that lead to so much violence and so many killings of poor people of color today: Jordan T. Camp and Christina Heatherton are co-editors of the new collection of essays Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter.

Jordan is a post-doctoral fellow for the study of race and ethnicity in America at the Watson Institute for international and public affairs at Brown University. Christina is an assistant professor of American studies at Trinity College.

Hello, Jordan; hello Christina.

Jordan Camp: Hello.

Christina Heatherton: Thanks for having us, Chuck.

CM: Christina, let’s start with you. I know people probably know all of this, but let me give a a summary of what’s taken place over the last several days. First there was the shooting this week of Alton Sterling by Baton Rouge police. As CNN reported on Wednesday: “A day after video captured white officers pinning down and shooting a black man outside a convenience store in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, federal authorities are investigating the case. Alton Sterling, 37, is dead. The US justice department’s civil rights division is leading an investigation into what happened, and the president of the NAACP’s local branch is calling for the city’s police chief and mayor to resign. The shooting led to protests, as witnesses stated that Sterling was not holding a gun. But police found a gun in Sterling’s pocket after being killed. Witnesses say Sterling never went for the gun.”

Then, a day later, we had the killing of Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. Castile was shot four times while seated in his car, as he reached for his license and registration. He was killed in front of his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter.

My question for you, Christina, is what makes either of these cases unique, and what makes them like so many other killings by police?

CH: It’s terrifying that these killings are both so unique and so common. We put together this book Policing the Planet in an effort to figure out why. We were driven to figure out not only how people like Alton Sterling and Philando Castile died, but how they were forced to live.

A lot of the book looks at everyday surveillance, and the routine ticketing of low-level crimes of poverty, crimes of existence: everything from loitering, trespassing, and other things that people are forced to do when they don’t have a place to live (this is what killed Charly Keunang in Skid Row), or selling untaxed commodities (CDs or cigarettes, like Eric Garner or Alton Sterling), to routine traffic violations (for which Philando Castile and Sandra Bland where both killed).

We’ve been very interested in trying to figure out “broken windows” policing: how it works, how it has developed over time, and as you said, how it’s connected to neoliberal models of capital accumulation in cities, how it has incentivized police to enforce these low-level crimes of poverty, and the fatal consequences that have resulted.

CM: Jordan, how much do living conditions get lost in today’s discussion of police violence? Do we focus too much on the deaths and not the lives that people lead with police? What do we lose in our understanding of police violence when we only consider the deaths and not the lives under police surveillance and scrutiny?

JC: Part of the media frame is to render each of these instances exceptional or singular, and it takes it out of the necessary political and economic context. There is a social and economic crisis that’s being disproportionately felt by poor and working class people of color in cities and ghettos and barrios all around this country and indeed the world. We’ve got a joblessness crisis—unemployment at Great Depression levels among the black and latinx poor (for decades)—combined with a shift in state capacities away from social budgets (education, healthcare, and housing), and towards the expansion of policing and prisons, where they can target non-criminal behavior. People are criminalized, essentially, for not having property in a rapidly gentrifying city.

What we want to argue is that these forms of policing—“broken windows,” so-called “community policing,” “neighborhood policing”—are political expressions of neoliberal capitalism at the urban scale.

CM: Then we have the shooting of twelve Dallas police officers, five being killed, in what the Dallas Morning News called “an ambush by snipers” (although it’s now been determined that there was only one shooter). In the wake of those shootings, Kai Wright posted an article at the Nation headlined “Black Lives Still Must Matter, Even After Dallas, but the attack is a reminder that no life will be safe and truly valued until we also confront the broader American culture of violence.”

Kai writes, “There’s no reason to connect the attacks to the hundreds of people who joined the anti-violence march in Dallas, or in cities around the countries this week. The Next Generation Action Network, which organized the march, has already condemned the shootings and called them ‘cowardly.’”

Christina, do you fear that the Black Lives Matter movement and their affinity groups will be blamed for these killings?

CH: There’s no doubt that they’ll be blamed. But as you said, the fault is not theirs. The statement that Black Lives Matter put out, emphatically distancing themselves from that kind of violence and vengeance, was right on target.

Recently we lost a towering figure in the field of black studies. His name was Cedric J. Robinson, and he was an incredible historian of the black radical tradition. Cedric Robinson said one of the defining features of that tradition is a pursuit of justice, not vengeance. And the Black Lives Matter movement, and all the movements that are fighting for the abolition of policing, are on the street for justice. If it were for vengeance, the rhetoric would be different, the tactics would be different, the organizing would be different. They’re not. This is a fight for justice; this is a fight for the basic implementation of the rule of law. This is a fight for justice, and not vengeance.

CM: Jordan, how do you fear the events in Dallas will change the national discussion on police violence?

JC: Of course, there is what scholars call a moral panic, where fears and anxieties about violence are appealed to in order to justify a response by the state that exceeds the actual threat.

I think if we look at this case in Dallas, it’s instructive that there was a choice made to use a robot to carry out an assassination, which even a mainstream liberal outlet like the New York Times says “blurs the line between policing and warfare.” It endows the police with the power to be the judge, jury, and executioner. My fear is that it could set precedence as a tactic, and open the way to predator drones, hellfire missiles, and domestic kill lists.

This moral panic about Black Lives Matter—about social protest, about people’s critique of a carceral state—obscures the actual source of violence, which is permanent war, policing, and prisons.

CM: Christina, one last quote from Kai Wright at the Nation: “Here’s the thing. The world is often more complicated than our political discourse accommodates. We are rarely allowed to use the word ‘and’ in our politics. But it is surely useful this morning [the morning after the shootings in Dallas]. We can and must condemn and organize against violence in all its forms—both violence against public servants and violence that public servants direct at us; acts of terrorism and state-sanctioned acts of war, hate crimes directed at a community of people and personal disputes that turn deadly due to the omnipresence of guns. What unifies all of this death is the grim reality that America is a horribly violent place. And if Dallas changes anything about the movement for black lives, it is only to remind us that in order to truly ensure black lives are valued, we will have to confront the broader culture of violence that has long gripped this nation.”

Jordan was just touching on this, but beyond racism, do we have to confront violence more broadly in order to stop the killings? And is it important for the Black Lives Matter movement to focus on the violence more than any aspect of race?

Trying to prove that policing is racist is like trying to prove that water is wet. I don’t think it’s for lack of knowing that people don’t respond. It’s for something else. That’s why organizing is so important right now.

CH: There is no separating racism from violence in the history of this country. As a number of our contributors to Policing the Planet—activists, scholars, journalists and artists—made clear, we have to understand the violence of “broken windows” policing within a long continuum of ongoing, foundational, colonial, imperial, racist violence that produces the US political economy.

Correct me if I misunderstood your question. But I do want to add something: Black Lives Matter didn’t actually come out of police killings. It was first a response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin—a vigilante-style killing. Throughout the book, we not only detail different police murders, but also vigilante-style killings such as Zimmerman’s murder of Trayvon Martin.

For example, there is an interview with Red Nation, which is an indigenous, native-led council in Albuquerque, New Mexico, that’s been organizing around the vigilante murders of two Navajo men named Rabbit and Cowboy. They say we have to understand the totality of this violence. When we have the state authorizing these extra-judicial killings, with impunity coming in various forms, this becomes a mindset, a common sense that people adopt. George Zimmerman appointed himself what Vijay Prashad calls a “human drone.” He thought he had located violence in the landscape, and he thought, at Jordan said, that he could act as judge, jury, and executioner.

These foundational violences come together in the daily practice of policing, and in the daily practice of vigilante violence and killing. It’s certainly not simple as a tagline, but it’s something that we have to confront in its totality.

CM: Jordan, what do you say to someone who argues the reason the police are focused on poor people of color is because of poverty leading people to do desperate things, including committing crimes, and poor people of color are more likely to commit crimes? Any time I have a conversation with anybody about Black Lives Matter, they often point to the responsibility of the people who are being targeted themselves.

What do you say to somebody who argues that this is all just a greater issue with poverty and not as much to do with racism or violence?

JC: This argument reproduces a racial “common sense” that has underpinned the largest buildup of policing and prisons that this planet has ever seen. It distracts us from the causes and consequences of this unprecedented transformation of police and prisons at all scales of the political economy.

The justification for “broken windows” policing is often presented as a race-neutral response to criminality. As your question suggests, its disproportionate deployment in poor communities of color has been justified as merely statistical inevitability.

So when people say this I think they unwittingly echo somebody like William Bratton, who asserts that the mass arrests of African-Americans and latinxs stems from intractable racial disparities, and who commits (and suffers from) crimes and disorder. His argument is that African-Americans and latinxs are not targeted in policing campaigns, but rather are subject to mass arrest because they’re the greater proponents of violence and crime.

Such circular racial logic has been a key legitimating instrument for a wholesale transformation of policing in American cities. The thing is, this arbitrariness is so widespread you have people getting arrested for, say, an open container in a black neighborhood, but if you went to a wealthy white district in Chicago, you can’t tell me that they’re doing mass arrests of champagne drinkers.

The contradiction is blatant. People are arrested for jaywalking in huge numbers in poor communities of color. That’s just not happening where I walk in Providence, Rhode Island, outside of Brown University. So we need more sophisticated analysis of the complex relationships between racialization, criminalization, and the political economy of policing and prisons, which we believe the activists and authors in our book make a contribution towards.

CM: Christina, just to follow up on what Jordan was saying, I’ve told this story on the air before: I was waiting for a train up here in Evanston, Illinois, just north of Chicago. Evanston is a very mixed suburb, but this part is predominantly white and wealthy. I was talking to an African-American gentleman at the train stop one time, and he told me, “This town is great. I absolutely love this town. I’m from Englewood on the South Side, and you can’t sit in your back yard and drink a beer. You can’t sit on your front porch and drink a beer without the cops messing with you. And you can do that here.” That really opened my eyes.

How much of the problems that the racialized poor face when it comes to police relations is just simply not known by those who are not in the racialized poor, which leads to the continuing process of the only solution being more cops?

CH: The common sense of “broken windows” policing is the following: when your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. I take your question in two different ways. On the one hand, there’s the question of whether people know or not. Sometimes this work is a little crazy-making, because proving that policing is racist is like trying to prove that water is wet. I don’t think it’s for lack of knowing that people don’t respond. It’s for something else. That’s why organizing is so important right now. Things are only going to shift if there’s a critical mass of us demanding change. I have a lot of hope, with all of the people organizing in the streets, because that’s the only way things are going to change.

But the other part of your question gets at how police work is incentivized. Recent developments have shown us a few different aspects of this. The Feguson Report that came about after the killing of Mike Brown and the uprising in Ferguson showed what happens when police are being deployed as revenue generators. Some twenty percent of the Ferguson municipal budget came from low-level tickets for things like broken taillights, people not driving with seat belts, people jaywalking, people playing their music too loud. Just ridiculous low-level crimes of poverty. A whole vast range of “crimes” for which, as Jordan said, it depends on the area you’re in whether it counts as a crime or not. What Ferguson revealed is that when police are incentivized to be revenue generators for their local municipality, it means that they excessively enforce the law and prosecute people for crimes of poverty who cannot afford to pay their tickets for citations.

Then those tickets lapse into warrants. The condition that we’re looking at across the country is that people are walking warrants. People have unpaid tickets, and they have a stamp. They have marks of removal. Any person can be pulled over at any time on the suspicion that they have a warrant. In her dissenting opinion for the recent case of Utah v. Strieff, supreme court justice Sandra Sotomayor made this point emphatically. She said that in federal and state databases there are 7.8 million outstanding warrants, and people live under the continuing threat of being stopped, searched, arrested, removed, or deported.

If I could say just one other thing: not every situation is Ferguson, but that doesn’t mean that policing doesn’t happen in a very similar way. We spend a lot of time in the book talking about Ferguson, but also places like Skid Row in Los Angeles, where police are also enforcing “quality of life” ordinances, crimes of poverty—not because those infractions are funding the local budget, in this case, but because police are essentially clearing spaces for new capital investment. In Ferguson there are 21,000 people; there are 24,000 warrants. There is a similar level of disproportionality in places like Skid Row, but the reason for the policing is different. The reason is removal. The reason is trying to refashion the landscape for new capital investment. We need to understand that dynamic.

In the name of reform, police departments say they will do “community policing” and “have sweet tea with the neighbors,” but what they’re actually trying to do is get access to more funding. But we know that what works is less.

CM: Jordan, let me just follow up on that real quick. The solution, as I was saying to Christina, has always been more cops, or more cops of color, or more cops with some sort of sensitivity training. Yet we still have all of the problems that we are facing, even in the wake of the Ferguson Report.

So Jordan, to you, why have all of these solutions not only fallen short, but why are they persistently pursued if we know, and we have seen historically, that they don’t work?

JC: Partly it has to do with our impoverished understanding of racism and policing. As Naomi Murakawa (one of our contributors) points out, Obama and his Commission on Twenty-First Century Policing define racism as an outcome of a few bad apple officers, and what we need to do is contain it, and as you suggest, do some diversity trainings or hire more black police officers. The problem with this is that it obscures the ways in which we’re dealing with structural racism. The tradition of what Murakawa calls “liberal law and order” has been right at the root of the buildup of the largest carceral apparatus on the planet.

The purported distinctions between “broken windows” policing, “community policing,” and “neighborhood policing” matter very little when it comes down to funding structures. In the name of reform, police departments say they will do “community policing,” and sit down and “have sweet tea with the neighbors” (as one of our contributors, Justin Hanford puts it), but what they’re actually trying to do is get access to more funding for more police officers.

But we know that what works is less. We need less contact between police officers and people, and what people like Ruth Wilson Gilmore and others have encouraged us to think about is a shift in state capacities away from policing and prisons and towards education, healthcare, housing, or what Prashad, in his chapter, describes as a “social wage.” If we want a more capacious solution to the current crisis, we need to revive this forgotten idea of the social wage as a solution to the policing crisis.

CM: Christina, you guys have been talking about “broken windows” policing, and I’ve been a little bit negligent in not defining that, in case people just don’t know what it is. It is the maintaining and monitoring of urban environments to prevent small crimes such as vandalism, public drinking, and toll-jumping, a process that helps create an atmosphere of order and lawfulness (supposedly), thereby preventing more serious crimes from happening.

Is there any evidence, Christina, that broken windows policing works?

CH: I think it depends on what you mean by “work.” Broken windows policing came to fame with a 1982 article in the Atlantic magazine by George Kelling and James Q. Wilson, with support from the Manhattan Institute, which is a rightwing think tank that has been promoting broken windows policing ever since. According to their propaganda, it works.

But the question put forward by social movements and activists ever since is: what definition of “order” are you using? Broken windows policing is usually seen as an enforcement of what are called “quality of life” ordinances. All the things you mention—loitering, public drinking, trespassing, etcetera—these are seen as infringing on the quality of life of some people. But if we think about the political economy of the United States over the past thirty years—when there has been wage stagnation, mass unemployment, mass criminalization, mass incarceration—we frankly have a lot of people who are engaging in behaviors that can be called “quality of life violations.”

How do people prove this? The number of people who are arrested who have no place to go, so they get arrested for loitering? The number of people who are arrested because they, like Philando Castile, have been pulled over dozens of times for petty traffic violations? When people are arrested and sent to prison, that might be an advance and a success for some people, but for most people in this country, that’s a carceral state. That’s not a success.

CM: Jordan, you write, “As de-industrialized cities have become veritable landscapes of broken windows, replete with abandoned homes, job sites, and factories, policymakers and police departments have utilized the logic of broken windows to locate disorder within individuals, offloading liability into the bodies of the blamed.”

So to what degree is broken windows policing just the state reacting to the job losses they created via globalization and trade deals like NAFTA?

CM: We argue that broken windows policing is an expression of neoliberalism. It’s a strategy of managing the surplus populations that have been produced due to the gutting of the social infrastructure and capital’s abandonment. We have to think about the closing of factories in cities all across this country. When people are out of work, there are social consequences of joblessness. The state’s organized political response to this social and economic crisis has been to criminalize poor people and people of color, the dispossessed, who have been produced out of this transformation.

Broken windows policing is often touted as bringing down crime rates (a big “turnaround,” as Bratton and the Manhattan Institute like to say). But there is no evidence to suggest that broken windows policing brings down crime. There’s no link between policing these low-level offenses and bringing down violent crime and disorder. Returning to your question, de-industrialization means that we have to look at the deeper political and economic roots if we want to imagine a different future.

Organizers, activists, and intellectuals all around this country are doing just that. In Chicago, Black Youth Project 100, We Charge Genocide, and Assata’s Daughters are groups talking about a divestment campaign from policing and a reinvestment in the public sector, or what they call “funding black futures.”

Partly, our intervention with the book is that we need to learn to listen to these young organizers who are creating a future in the present.

We need to defund the police. We need to fund things that produce life in our culture. If we don’t, we’ll continue to have the barbarism that we’re currently living through.

CM: And Christina, you write, “Vijay Prashad provides a theory for understanding the political economy of racism in his essay This Ends Badly: Race and Capitalism. The task, he argues, is to develop a framework of an alternative including universal access to economic power and a social wage. This framework, Prashad concludes, should be taken seriously by all or else the ‘common sense’ of our times will lead us to a bad end.”

In your opinion, how bad can this end, Christina?

CH: We’re seeing the potential all around us. Summary executions.

Philando Castile’s girlfriend [Diamond Reynolds], the remarkable and brave woman who filmed her boyfriend’s assassination by the police, said at her tragic press conference that she doesn’t understand why we have all this money for things like stadiums but we don’t have funds for things like Philando’s funeral. She made a plea that the state should fund his funeral, which is just heartbreaking in every sense. At the heart of it is that we have to have big imaginations of who we are, what we want, what we have the right to claim from the state, and what kind of a world we want to live in.

Because we shouldn’t need to tax the state for funerals. We should be taxing the state for life-generating processes, for what Prashad talks about in that article: a social wage, like Jordan said, or taking money out of police and prisons, stopping the process whereby police and prisons become a catch-all solution to all our problems, stopping the process whereby police end up being school disciplinarians, public housing managers, guardians against public park trespass. The police should not be performing these social functions. We need to defund the police. We need to fund things that produce life in our culture, this is what Prashad is saying. If we don’t, we’ll continue to have the barbarism that we’re currently living through.

CM: Jordan, any time I mention Black Lives Matter, somebody says “I think all lives matter.” Is there an issue with the branding of the Black Lives Matter movement? And what’s wrong with saying all lives matter?

JC: What’s wrong with it is it displaces the anti-black racism, the state violence, the mass criminalization, and the structural unemployment that the black working class and black people have borne the brunt of for centuries. This crisis has been particularly acute in the neoliberal era.

On one level, why should we have to even assert that black lives matter? There’s been some debate about this. But “All Lives Matter,” or the even more egregious “Blue Lives Matter” campaigns are to distract us from the demands, the critique, and the social vision that has been articulated by this most recent phase in the history of the black freedom struggle.

That doesn’t mean that you have to agree with everything that people say, but it does mean you have to learn to listen to the cries emanating from the soul of this nation. I don’t think that we’ve learned to do that yet. I’ll say again: if you’re in Chicago, I want you to learn. Read the documents of the Black Youth Project 100. Try to go and see the rallies. There is an explosive struggle for a new society erupting all around us. In Chicago when they shut down the Dan Ryan expressway, they showed us not only that black lives matter, but that black resistance matters. We need to learn from this moment, because alternative futures are not only possible, they are absolutely necessary.

CM: Jordan and Christina, I really appreciate you being on the show with us this week.

JC and CH: Thank you very much.

Featured image source: Assata’s Daughters (Facebook)