Bringing Back Walter Rodney

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

by Kofi Shakur for Klasse Gegen Klasse

19 April 2017 (original post in German)

Why are African countries “underdeveloped”? And how did the imperialist plunder of the continent begin? Was slavery a product of racism? Or did racism rather emerge out of the economic exploitation of the African labor force? The Guyanese anti-imperialist Walter Rodney delivers materialist answers to these questions.

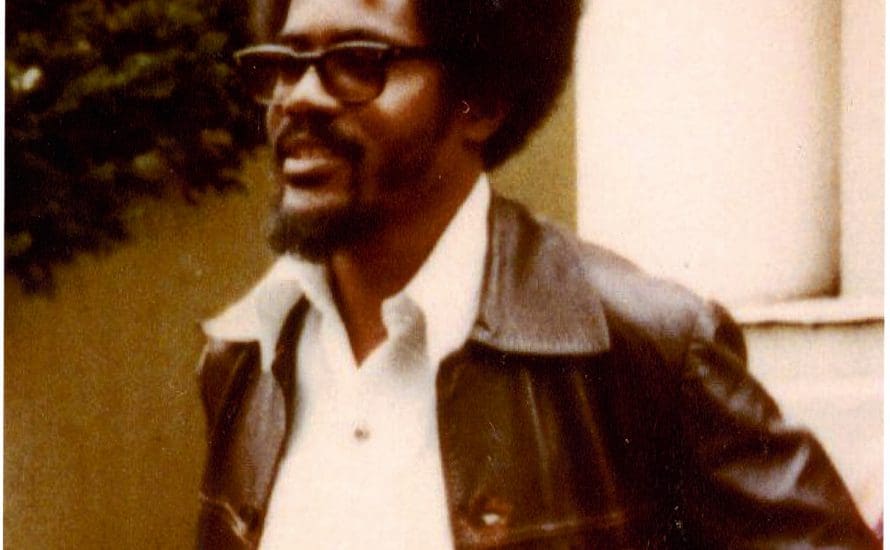

The British dub-poet Linton Kwesi Johnson (LKJ) dedicated a song to him after he was killed, in 1980, by a bomb set in his car. And even today people remember the “Rodney riots,” as they were known, that broke out among university students in the West Indies in 1968 when the Jamaican government barred him from teaching after he traveled to Cuba and the Soviet Union. Who are we talking about? None other than the anti-imperialist fighter Walter Rodney.

In concert, LKJ frequently name-checks the title of Rodney’s book, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa—the title of the German publication, it should be noted, was Afrika: Die Geschichte einer Unterentwicklung [Africa: A Story of Underdevelopment]. This is not merely a poor translation but a crude watering-down of the book’s politics, which are essential to understanding the current state of affairs on the African continent.

In the book, Walter Rodney conducts a deep investigation into multiple African cultures and states in the time before they were shaped by the slave trade and imperialist resource exploitation, and describes their continuing modes of development. By way of these case studies, a picture emerges of the economic and social structures of these societies up to and through the introduction of feudalism and the formation of the state.

Where does racism come from?

His explication of the origins of racism is one of the achievements for which Rodney should be recognized. Against a still-widespread misapprehension, he writes:

Occasionally, it is mistakenly held that Europeans enslaved Africans for racist reasons. European planters and miners enslaved Africans for economic reasons, so that their labor power could be exploited. Indeed, it would have been impossible to open up the New World and to use it as a constant generator of wealth, had it not been for African labor. (…) Having become utterly dependent on African labor, Europeans at home and abroad found it necessary to rationalize that exploitation in racist terms as well. Oppression follows logically from exploitation, so as to guarantee the latter. Oppression of Africans people on purely racial ground accompanied, strengthened, and became indistinguishable from oppression for economic reasons.

He later gives a similarly incisive treatment, with a detailed account of the development of the company Unilever into a monopoly at the expense of Africa, to the well-worn lie of feel-good colonialism: that it also benefited Africans. The streets, schools, hospitals, nearly all the infrastructure projects—the benefits of which are still touted by European world-savers—were built either in direct service of the export of natural resources or were amenities meant exclusively for whites. The absurdity of the local-benefits argument should become clear, at the very latest, when one reads of a British colony achieving nearly British living standards for the colonists while untold thousands of Africans had one doctor.

This makes it evident that the underdevelopment of the African continent is not a result of the racial-essentialist inferiority of either Africans or their societies, but rather of the intentional activity of the slave trade and colonialism as such. Only the enormous destruction and appropriation of knowledge, the monopolization of natural resources and the exploitation of the black labor force—in other words, the brutal assertion of capitalist and imperialist interests and the interests of the European bourgeoisie—can explain the current status of African nations as “developing countries.” Still today it is the unholy alliance between imperialist states and local bourgeoisies that is responsible for the subjugation of the semicolonized. With regard to the struggle against imperialism, for Rodney it was therefore all the more important to emphasize that the fight for emancipation and independence could only rise out of the self-organized politics of the exploited and oppressed themselves.

Not a popular front—meaning a coalition with the local bourgeoisie—but an independent organization of the proletariat is necessary in the semicolonies, above all since it is not uncommon for local bourgeoisies to be assigned the role of viceroys: they function as agents representing the interests of imperialist companies, in order to benefit in return from their privileged position and connections to them. It is also not uncommon for these same people to simultaneously employ nationalistic jargon in the guise of “independence,” only to betray the interests of their own people. Well-known examples are Blaise Compaoré [Sierra Leone] or Joseph Kasavubu [Congo], who in cooperation with French and American imperialism, respectively, were responsible for the murders of anticolonial fighters in their countries.

Exploitation of the African Continent

Rodney did not limit himself, however, to the examination of colonial oppression from a Marxist perspective, but also investigated the precise role of the exploitation of the African continent in the process of capital accumulation by the European bourgeoisies. He described, among other things, the complete plunder of entire countries which had been, for example, completely covered over by monocultures, causing hunger and misery for their whole populations. These landgrabs were highly lucrative for capital interests, who could at once increase exports and take advantage of a cheap, desperate labor force. Franz Fanon similarly demonstrated the significance of imperial rule with the following analogy:

Colonialism and imperialism have not settled their debt to us once they have withdrawn their flag and their police force from our territories. For centuries the capitalists have behaved like real war criminals in the underdeveloped world. Deportation, massacres, forced labor, and slavery were the primary methods used by capitalism to increase its gold and diamond reserves, and establish its wealth and power. Not so long ago, Nazism transformed the whole of Europe into a genuine colony. The governments of various European nations demanded reparations and the restitution in money and kind for their stolen treasures. As a result, cultural artifacts, paintings. Sculptures, and stained-glass windows were returned to their owners (…).

At the same time we are of the opinion that the imperialist states would be making a serious mistake and committing an unspeakable injustice if they were content to withdraw from our soil the military cohorts and the administrative and financial services whose job it was to prospect for, extract, and ship out wealth to the metropolis. Moral reparation for national independence does not fool us and it doesn’t feed us. The wealth of the imperialist nations is also our wealth. (…) In concrete terms Europe has been bloated out of all proportions by the gold and raw materials from such colonial countries as Latin America, China, and Africa. Today Europe’s tower of opulence faces these continents, for centuries the point of departure of their shipments of diamonds, oil, silk and cotton, timber, and exotic produce to this very same Europe. Europe is literally the creation of the Third World. The riches which are choking it are those plundered from the underdeveloped peoples.

About the colonial division of labor which occurred within the process of exploitation, Rodney has this to say:

No industry meant no generation of skills. Even in the mining industry, it was arranged that the most valuable labor should be done outside Africa. It is sometimes forgotten that it is labor which adds value to commodities through the transformation of natural products. For instance, although gem diamonds have a value far above their practical usefulness, the value is not simply a question of their being rare. Work had to be done to locate the diamonds. That is the skilled task of a geologist, and the geologists were of course Europeans. Work had to be done to dig the diamonds out, which involves mainly physical labor. Only in that phase were African from South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Tanganyika, and Sierra Leone brought into the picture. Subsequently, work had to be done in cutting and polishing the diamonds. A small portion of this was performed by whites in South Africa, and most of it by whites in Brussels and London. It was on the desk of the skilled cutter that the rough diamond became a gem and soared in value. No Africans were allowed to come near that kind of technique in the colonial period.

By the same token, in an interview about the situation in the country of his birth, Guyana, with a keen look at its societal structures, Rodney explained that he recognized and agitated against not only the specific racist oppression of black and Indian workers as blacks and Indians, but their exploitation and oppression as workers as well, calling for united struggle.

In view of the tasks ahead, it is a necessity for us to reacquaint ourselves with the research and findings of Walter Rodney. If we truly want to build a forceful movement against racism and the imperialist interests of German capital, we must fight still-pervasive false perspectives on the cause and function of racism, and put a historical-materialist analysis up to challenge them.

Translated by Antidote