Transcribed from episode 44 of the Solecast and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to and download the whole show here.

The syndicate was a network of anti-racist skinhead crews and antifascist crews that were ready to hunt down Nazis in their cities. That was the beginning of what came to be known as Anti-Racist Action, ARA. We understood that in order to confront violent racists, we couldn’t just do it ideologically, and we couldn’t just do it with words and language. We could do all of those things, and we were doing all those things, but we also had to be willing to find them where they were and fight them.

Sole (Tim Holland): Today’s guest is Mic Crenshaw, a rapper, organizer, educator, and poet. He helped start the Anti-Racist Action network in the late eighties, which later went on to become one of the largest antifascist organizations in North America in recent history.

With all that’s been happening lately, I just wanted to pick his brain about what they did back then, and what’s changed, and how we can apply the lessons of Anti-Racist Action to today’s struggles.

We also talk about what we can do beyond being reactive and start to build those actual networks of mutual aid and solidarity and community defense. That shit has never been as important as it is now.

We’re also going to talk about the work he’s done and continues to do in Africa, his involvement in the Hip-Hop Caravan which travels all around the continent in Africa, and the work he’s done up there to build community centers and computer centers [AntiNote: We have removed these sections to keep things tight, but we encourage you to go check out the audio because there’s great info in there]. This guy has done so much amazing shit. He makes awesome music, he’s in the streets, he’s in the struggle, and he’s lived a life dedicated to revolutionary action.

We just got into it: he started talking about some real shit in Portland recently where some people got stabbed, and he knew one of them. The survivor was a really good friend of his. I just hit record as soon as he started talking.

Mic Crenshaw: This is a result of a historical process, and I see the escalation of volatility on the streets, in society. In certain ways, I feel like we were born for this, those of us who are engaged in the antifascist movement and struggles, but it doesn’t really take away the anxiety.

TH: That person who got stabbed, that was your friend?

MC: Yeah, he’s a comrade of mine. He’s a dope MC, dope lyricist, dope spoken word artist. Young guy, 21 years old. He’s the type of person who stands up for people. That’s actually who he is. When I heard about the stabbing on the news I immediately wondered if I know anybody involved in that. In the morning I got the text that the comrade was in the hospital, so I went and visited him. He made a speedy recovery. I saw him last night. He’s been out. He was only in the hospital for a couple days. But he got hit so hard in his neck with the knife that it broke his jaw.

TH: You know, I have a friend who works at a refugee spot out here, and she was saying how the people who work there got followed home and assaulted by white supremacists and were stabbed; that wasn’t even in the news. Another comrade’s partner in another city got followed home after the anti-sharia stuff last week, and she got beat down by four Proud Boys. It’s like, what the fuck? These are women getting beaten up by men in both of these instances.

MC: I keep hearing of these instances (and like you said, a lot of it isn’t making the news). Two grown men confronted grade-school children because the kids were taking down some fliers or something. I don’t have all the details, but to make a long story short, we have these racist grown adults threatening children, and beating up women. That’s not okay.

TH: The irony here is these anti-sharia marches that were happening were under the guise of liberal values and women’s rights. Alright then, you’re going to hide behind the cops, call women bitches and then follow them home and beat the fuck out of them. That’s some grade-A American feminism.

That’s why I wanted to talk to you about this shit. When we met, I didn’t know your history as an activist. Then Scott Crow was like, “Oh, shit, he started the Anti-Racist Action network.” So let’s rewind it a little bit and go back to how your anti-racist work really got started.

MC: I was a teenage kid in Minneapolis. I moved up there from Illinois; I’m originally from Chicago and moved around a lot. By the time I got to Minneapolis I didn’t really fit in, and I was tired of always going to new schools and trying to find new friends. That’s when the hardcore punk scene started to appeal to me, because I started meeting people from that scene, and I was like, well, these guys aren’t trying to fit into the mainstream social cliques. The music that they were listening to spoke to me, because it was hard, and it had a lot of energy, and it had a message.

So I started hanging around that scene and making friends inside the scene. My group of friends and I started rolling around together, and at the time we were straight-edge. We weren’t drinking or doing drugs. Skateboarding together. It was me, this brother J*, who’s a native American kid, a couple working class white kids. There were about seven of us at first. And we picked up a copy of the book Skinhead by Nick Knight. We identified with that culture. We liked the look, we liked the working class roots of it, and we were ready for action. We wanted to be little tough guys.

And right around that same time, those shows like Sally Jessy Raphael and Donahue and Geraldo Rivera started giving a platform to all these white power boneheads. And we were like, that shit is wack! But within a matter of days, people started emulating that in Minneapolis, and we started to see these kids who really didn’t know anything about the two-tone roots of skinhead culture who were just copying what they saw on TV, and they started showing up in the areas where we were hanging out, and coming to shows, and we got wind that some of these guys were white power—they were calling themselves the White Knights—so we confronted them. We were like, “That’s not going to fly around here. We’re going to give you a chance to denounce that shit, and the next time we see you, if you’re still claiming white power then there’s going to be a problem.”

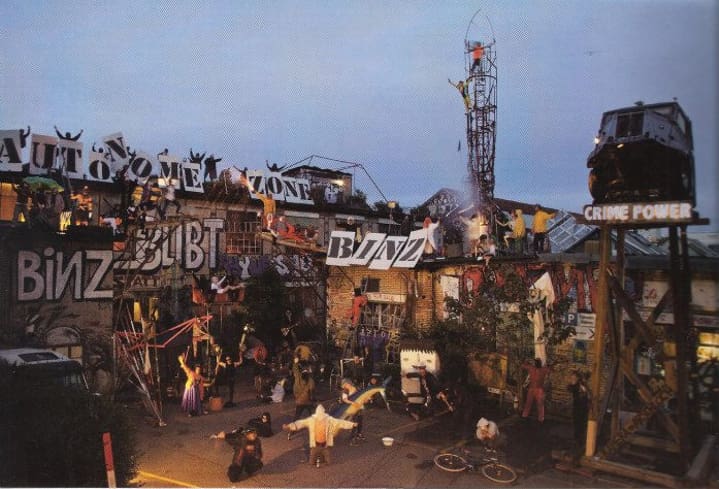

That was the beginning of it all. We intentionally called ourselves the Minneapolis Baldies, because so many people were watching stories about skinheads in the media and reading it in the magazines and stuff, and all of them identified skinheads with Nazis. There was no popular media stories at that time, no mainstream media coverage of the real roots of the skinhead subculture. Everyone defined them as Nazis, so we wanted to differentiate. We felt like we were true skinheads. We were truer to the authentic roots of the culture. Plus, we also understood that in United States gang culture, in numerous cities, there had already been Baldies cliques: there were Fordham Baldies in New York, and there was actually an older Minneapolis Baldies in the fifties and sixties.

Once we confronted these guys, who were led by a member of the Klan, that began a protracted period of violence on the streets, where we would see them and we’d fuck them up. And sometimes they’d see us, and we’d be outnumbered, and they’d jump us. We were carrying weapons everywhere, and shows were often violent, and we decided that we needed to build allegiances with people outside of our immediate clique, which had grown to about thirty. So we started to reach out to some of the black and Latino gangs, people in the native American community and their street organizations, and we started to build an allegiance with people who would take a stand in fighting against these white power skinheads.

Technology, in addition to the globalization of labor and deregulation, where you only have to pay people a dollar a day, has created this society in which people are no longer necessary or employable. That allows the vanishing of entitlements to create the need for scapegoating, for extra policing, and the need for a constant war machine (as our only export). It’s in this petri dish that fascism emerges as a natural response.

In addition to that, we built with other punks and anarchists in the scene at that time, specifically the Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League. We used the anarchist bookstore (the Back Room Bookstore in Minneapolis) as a center for organizing, meetings, and cultural events. And eventually we reached out to people in other cities who were having the same problems. There was Madison, Wisconsin; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Chicago, Illinois (we had strong allies in Chicago); Lawrence, Kansas. A lot of cities in the Midwest. And I think it was in about ’87 or ’88, we had our first meeting that was multiple cities: over a hundred anti-racist skinheads and antifascist activists from different cities came to Minneapolis. We had a meeting at the library, and we formed this syndicate.

The syndicate was basically this network of anti-racist skinhead crews and antifascist crews that were ready to hunt down Nazis in their cities. That was the beginning of what came to be known as Anti-Racist Action, ARA. Because we understood that in order to confront violent racists, we couldn’t just do it ideologically, and we couldn’t just do it with words and language. We could do all of those things, and we were doing all those things, but we had to be willing to find them where they were and fight them. That was the beginning of that culture.

Little did I know at that time that simultaneously there was an antifascist movement happening in Europe that mirrored what we were up to. I didn’t find that out until later.

TH: How did you do it without the internet?

MC: You know, there were zines. There was a punk zine called Maximum RockNRoll. There was another one called Your Flesh, and in these zines, these black-and-white paper rags, there would be scene reports from different cities. You could go down to Shinder’s bookstore and they had these zines. They maybe cost 25 cents. You’d buy them and you’d look in the back, and there would be reports from the west coast, the southwest, the east coast. And you started to see that these people are fucking having Nazi problems everywhere, and you’d reach out to people in those scenes.

There were some of us in the punk scene who traveled a lot, or people who were in bands that were on tour and so they would meet people from different scenes, and they’d hear about what was happening in those cities, and they’d get people’s contacts. You’d go in your kitchen, and you’d pick up your clunky telephone and dial the number and call somebody. Or you’d go to a phone booth!

But we built the network that way, and that network even came all the way out to Portland. Before I moved to Portland from Minneapolis, there was a network of SHARPs, Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, out here. I knew I had a home out here on the streets if I wanted it. When I got here, those were the first people I networked with and built community with here in the city, and we’re all still friends and comrades to this day.

It’s a trip right now, because it’s thirty years later, and here we go again. We’re all grappling with the differences between what we faced in the Reagan era and what we’re looking at right now.

TH: What are those differences? How have things changed? What’s new?

MC: Subjectively, those of us who were involved on a personal level, an individual level, we’ve all grown older. Those of us who didn’t commit suicide or get killed or succumb to some disease—those of us who are still around and who kept being relatively active—we have more to lose. A lot of us have families. Some of us have careers that we love. So there’s that very personal reality. The willingness to go out into the street and engage, and even actively hunt down violent racists is something that is different when you’re middle-aged. The way you orient yourself and the thought process around the types of decisions you make, around personal safety and security and potential incarceration and death—it’s different than when you’re a teenager. It just is.

There’s also the external reality that the state has escalated the way that it criminalizes and prosecutes and convicts people for political organizing and political violence. We see historically that the state has not only protected white supremacists, but in a more convoluted sense, it seems as if they allow white supremacists to operate under these bullshit constitutional protections of freedom of speech, knowing that they’re going to provoke and incite violence, and then they use that opportunity to then go after the antifascists and the anti-racists and criminalize them for responding to the white supremacist threat. So we know that there’s a lot more at stake in the way that the state responds to our activity, especially if it’s going to include person-to-person violence or organized violence.

Third, there’s the surveillance aspect, passive surveillance. The state obviously has their overt and covert surveillance. But what I call passive surveillance is the fact that there are fucking cameras everywhere. People aren’t always aware of the fact that what they do is being recorded by cameras that might not intentionally be trained on the activity, but because of security paranoia and the prevalence of technology that’s affordable to business owners, there are cameras everywhere.

Lastly there’s the device culture that we live in. Everybody’s got a telephone, and everybody’s recording shit. If they see something interesting, if they see violence, they want to take out their telephone and record it. All of these things come into play when we think about what’s at stake when you decide that you have to take a stand and confront somebody. The consequences of that have to be part of our consciousness, and have to be part of our organizing strategy when we’re trying to figure out how to engage these people.

Back in the day, you find out where they are, and you go fuck them up. Now there’s a lot more to it. And at a lot of these rallies and demonstrations, we’ve been taking losses. We’ve been going out there and publicly getting our asses handed to us. Getting stabbed. And these guys are being protected. There are a couple of these fascist fuckers who have been going around beating people on camera, like this Based Stickman character, and then they get canonized as heroes in the media, and they’re allowed to walk around freely and do this. Whereas I know if I were on camera kicking someone’s ass in three different cities, I’d be gone for like 25 years.

It’s an interesting time. The racists, the right wing, the religious right, the Proud Boys, all these different toxic conservative elements have been emboldened by the atmosphere created by this administration.

Around the end of Occupy I started to see this thing happen that I also saw in the eighties, where the radical left was more eager to call each other out and tear each other down than to produce any type of real meaningful base of activity for the working class to seek liberation in their communities. There became this insular infighting culture that I didn’t want to have anything to do with.

TH: And we think Trump is bad, but what’s coming next? Trump could be just one step towards whatever’s coming.

MC: To use leftist rhetoric, we’ll call this late-stage capitalism. To elaborate on that: it’s the development of technology and how that’s changed the means of production in a society that came into wealth and privilege and prestige on mass manufacturing from the war effort, which led to the auto industry, and so on. Those things, going all the way back to chattel slavery, mass production at the cotton plantation, the exploitation of free labor, and the profits that were consolidated off of that, led to the development of the industrial age, and in the interest of profit we’ve arrived at a situation were there sentiment is, “Why would I pay a human being a fee to do for me what I can get a machine to do for free?” So as my man Waistline out of Detroit so eloquently points out, if you can get a machine to do in an hour what it used to take an assembly line of human bodies a whole day to do, in the interests of profit you’re going to go with the machine.

Trump came into power telling people he’s going to bring back coal mining. Even people in coal country know there’s no way that’s coming back. Because it’s not profitable. How can you compete? There’s this whole hipster thing going on where people want to hand-carve handlebar mustache trimmers or whatever the fuck they’re into. That’s cool, it’s a novelty thing from a bygone era, but the fact of the matter is in a capitalist society, if you want to compete, you have to be able to produce more, you have to be able to produce cheaper.

So the technology, in addition to the globalization of labor and deregulation, where you only have to pay people a dollar a day or whatever, has created this society in which people are no longer necessary or employable. That allows the vanishing of entitlement to create the need for scapegoating, for extra policing, and the need for a constant war machine (as our only export). It’s in this petri dish that fascism emerges as a natural response. It’s logical that fascism is going to be escalating and on the rise right now. This is part of a process we’re in that’s not going to fucking stop.

So the question is, what do we do in response? And not just defensively, not always on some reactive, reactionary shit. How do we think proactively, long term, so that we can have quality of life that’s not just us responding to brutal repression?

As a cultural activist who’s been a professional hip-hop performer, an MC rocking shows and all that, I was able to exist in a bubble for a while. I was able to channel a lot of my political consciousness and political activity. Not only am I rocking shows and recording and releasing music and touring, but I’m going into the schools and engaging young people around these questions of how we not only face history and be aware of history, but how we can be accountable for this moment that we’re in and see our lives as not existing in a vacuum based on pleasure-seeking and devices and consumerism, but actually part of a process that we have a role to play in.

Doing those things allowed me to separate myself from the radical left in a way that was kind of intentional for a number of years, because around the end of Occupy I started to see this thing happen that I also saw in the eighties, where the radical left was more eager to call each other out and tear each other down than to produce any type of real meaningful base of activity for the working class to seek liberation in their communities. There became this insular infighting culture that I didn’t want to have anything to do with, specifically because in a lot of those spaces I was one of the only people of color. I was one of the only black people. I’ll be goddamned if I’m going to spend my time around a bunch of fucking white people who want to tear each other up. I’ve got more important shit to do.

So I stopped fucking with that scene for those reasons, and I see the same kind of thing happening now. We do the work of the state, for the state, by tearing each other up and rendering ourselves ineffective. What I’m looking at right now is: how do I organize, how do I take the skills that I’ve developed from years of organizing in left circles, in left movements—how do I take those to the broader working class communities that I’m actually from? What do I have to contribute to my black community, my working class black folks, my poor striving and struggling black communities, my lumpen black proletariat, my cats who are in their own ways already organized, coming from gang culture? I see these people as the people who I really need to be part of building a movement.

These racist attacks from all these different elements on the right are actually serving to pull some of us out of the woodwork who have been comfortable doing our own thing in our own way for a while, and bring us together and create this sense of unity around these questions. How do we not only defend our communities and ourselves, but how do we let it be known that that shit is not going to fly over here? If you come over here with that shit, you’re not going to fucking leave in one piece.

Take into consideration these critical questions around how the state engages us. How do we protect ourselves in an environment where we’re already hyper-criminalized as black folks in relation to the prison-industrial complex? There are so many divisive means and ways that are ingrained in the system, ways to get us off the street, out of our communities, and incarcerated, or in the fucking grave. From police violence where one of us gets killed every 28 hours, to this fucking mandatory minimum sentencing, where there are young people being sentenced as adults and going to jail for five to ten years, for life sentences, for something that really could be a teachable opportunity in the sense of restorative justice, or a moment to get people to take a critical look at the root causes of some of the ills we’re facing on the streets in day-to-day life.

But there’s a lot of complexity that we all have to be looking at in this moment, and it’s a pivotal moment. We have to stop and really take stock of how we got here. How do we figure out how to go forward and not always be on the defense? Because that’s just not sustainable.

The clarity that I get right now isn’t me as an individual going on some vision quest or something. The clarity that I’m getting is when I’m in rooms with people who are all thinking critically. I love being part of that work, because it’s bigger than me as an individual, and I feel that there’s a truth and an authenticity to the clarity that’s coming out of those moments.

TH: Right. The thing I struggle with is trying to find projects that are rooted in mutual aid and rooted in people’s needs, projects that can strengthen people but don’t become easily recuperated by the state. I’m one of these motherfuckers who loves the idea of urban gardens and guerrilla gardens, but all I’m doing is raising up property values. If I do it wrong, I’m just raising property values so some real estate person can kick out the people we built the gardens with.

Do you have any other ideas as to what those of us who are concerned with this moment and moving beyond reactive stuff—what are some projects you’ve seen? What are some things you’re thinking about that could be incorporated into the thinking and organizing that folks are doing?

MC: You mentioned community gardens. That conversation and that consciousness is not new, it’s been around, and I think it’s time that a lot of us who haven’t been involved in food justice and community control and control of land and geography in our communities started to learn about that in collective and cooperative ways, and learn with each other about the resources of the land and the space that we live on. How do we better use that land in a way that sustains and supports life, that is self-sufficient?

Communities could divest from the big-box corporate network of food distribution, and could take care of ourselves in ways where we’re trading and bartering and distributing surplus from our own gardens—be they individual gardens or community gardens—and sharing food in that way. Community defense committees are something that form as a defensive reaction to the right’s escalation of violence and the volatile political atmosphere on the streets and in our communities. But I think that we need to be looking at the community defense networks that we’re forming now and starting to think about long-term strategies.

Say this rash of violence that’s happening in cities goes away after a few months. When the weather starts to get cooler in a lot of these more temperate places that we live in, maybe some of the violence will go away, and people will kind of chill out. Then the networks that have been forming over the summer and prior need to be sustained. We need to understand that the camaraderie and the solidarity, the organization, the sharing of skills, and all the things that it takes to create community defense should be ongoing processes.

It’s only through committing to long term work that we start to get used to what we’re up to and it’s not such a shock anymore. What other ways can we apply these relationships and these skills that we’re not even considering right now because we’re always just responding to something?

I don’t have the answers, but I do know that the answers are going to come from me working with people. The clarity that I get right now isn’t me as an individual going on some vision quest or something. The clarity that I’m getting is when I’m in rooms with people who are all thinking critically. I love being part of that work, because it’s bigger than me as an individual, and I feel that there’s a truth and an authenticity to the clarity that’s coming out of those moments that’s not really available when I’m just thinking about me.

I guess that’s the silver lining, so to speak. What we’re experiencing right now is that people are developing clarity together that wouldn’t be available if we weren’t going through this.

TH: There’s talk about how some people do activism because they don’t have a social life; they do it as a replacement for a social life. But we shouldn’t be showing up to the struggle like it’s a fucking job. We should be breaking bread with the people who we are organizing with, whether that’s a barbecue once a month, informal meetups, sharing ideas. That’s what old-school organizers in Denver are all like: Fuck these assemblies, fuck all this shit. Let’s just fucking eat some food and listen to some music and talk some shit.

MC: Let’s be friends, man. Let’s be friends. Because when we’re friends, then we can be family. And when we’re family, we fucking stand for each other, we have each other’s backs. Yeah, we’re not perfect. But if we have a problem with each other, we can work it out. We can sit down and figure it out together because there’s some unconditional love there that’s built up over time.

An affinity group that formed off of Facebook last week—that’s something, and it can be useful. But you’re right. We’re going to have to eat together to build community, and when we were effective at what we were doing in the eighties, it’s because we were kids, and we were friends first. We spent most of the hours of the day together. We went everywhere together. We hung out together. We loved each other, and that was the energy that we brought to the struggle.

In this society we live in that’s based on the commodification of human labor and splitting everybody into units and the nuclear family and all that kind of shit, once people grow up and they get a career and they get money, they move on. Their self-interest about their little bubble becomes a priority in a way that actually doesn’t build community.

About the older activists who have moved on, but who actually have some skills and consciousness based on lived experience: we have a responsibility right now to come out of our bubbles and come into activity with some of these younger people who are newer. We have to. Because all we’ve got is each other. I hate to say it, because I never like to use language to give the enemy more power, but the right is organized. They are. Whatever their differences in ideology might be, they’re smart enough to go, “Well, I’m going to be friends with these guys right now because we have a common enemy.”

We’re going to get through this, man. People in history have gotten through worse. There are people on Earth right now who are going through a lot worse than what we’re going through here. We’ve got to be able to put it in perspective, and know that we were born for this moment.

Our processes of accountability are important. If we have internalized oppression and dysfunction that we’re acting out on each other in our communities and circles, we have to check that. But we have to figure out ways and means to check that stuff that’s not on social media, because the state uses that against us. And we have to be courageous and figure out how to devise healthy ways to communicate around accountability, where if you do something foul, I feel safe confronting you. We have to find ways to do that better, sustaining our relationships and making us stronger as individuals and as groups of people, as opposed to tearing each other apart.

That shit doesn’t help. We’re all wounded, because we live in a sick society. We’ve got multi-generational trauma from genocidal repressive imperialist reality, and we bring that to the table as individuals, and so when we throw people away, a lot of them just move on to another location and do the same shit all over again.

I’m somebody who considers myself a radical and a revolutionary, and a lot of the people who I mess with are anarchists. I have a lot of respect for different strains of anti-authoritarianism that I’m in solidarity with, and a lot of the thinking that I’ve developed in my own consciousness through struggle and through camaraderie with people has brought me to a place where I don’t want to actually say I’m an anarchist or a communist or a socialist—primarily out of respect to the people who do call themselves those things, who have read thousands more books than I’m going to find time to read.

I used to be involved in an organization called the Communist Labor Party, and some people in the leadership of that organization were some of the wisest revolutionaries I’ve ever met, who had a lot to do with my development, and a lot of those people went on to build alliances—very intentionally, very strategically, and very consciously—with people who weren’t and would never identify as communists. They understood that the need for a mass movement in this country isn’t based on being in a fucking clique of people who all agree on the same semantics. It can’t be.

When I’m in Africa touring with the African Hip-Hop Caravan, some of the best organizers I’ve ever met, young cultural activists who are also amazing artists—they’re anarchists. They’re very horizontalist and anti-authoritarian and anti-statist in their orientation to the struggle, because they’ve seen the promise of rhetoric turned into the same neoliberal state mechanics that oppress people the same way that colonial regimes did. Their relationship to anarchy isn’t about a uniform or even an identity as much as it is a political understanding that as long as the state exists, the power dynamic is going to be the same in relation to the masses. I can get with that. I’m not interested in ushering in some supposed new system that’s based on personality cults and hierarchy that’s just going to turn around and continue to fuck people. That’s not what I’m here for.

We’re going to get through this, man. People in history have gotten through worse. There are people on Earth right now who are going through a lot worse than what we’re going through here. We’ve got to be able to put it in perspective, and know that we were born for this moment. Whether or not you believe in some spiritual, metaphysical reality and all that kind of stuff, or whether you’re just a straight-up atheist and there’s nothing more than what’s happening, and when we’re done here, it’s all done—okay, fine. Then let’s be present and work with what we have and make the best of it.

These other motherfuckers are fucking cavemen. All the shit they say about us to justify the dehumanization that leads to the extermination of people (which is what their whole project is about)—that’s a mirror they’re holding up to themselves. So let’s continue, let’s go forward. La lucha continua, the struggle continues.

TH: Thank you, Mic Crenshaw, for coming through and blessing us today. Enjoy the weather, enjoy the summer, fight the power.