Transcribed from the 21 April 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The fact that it’s the poor who are paying the price is one of the reasons that the rest of us can just cruise.

Chuck Mertz: Climate change is happening, and it may already be in a state where it is completely outside of our control. And its impact is going to be a lot more intense, a lot sooner than we thought. Which means we’ve got to start thinking about the world in our climate change future. Here to help us do that, Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann are authors of Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of our Planetary Future.

Joel Wainwright is associate professor of geography at Ohio State University. He is the author of Geopiracy: Oaxaca, Militant Empiricism, and Geographical Thought, which won the Association of American Geographers Blount Award in recognition of innovative scholarship and cultural and political ecology.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Joel.

Joel Wainwright: Thanks, Chuck, it’s great to be here.

CM: Also joining us is Geoff Mann. Geoff is director of the Center for Global Political Economy at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. You may remember Geoff being on our show in the past when we talked about his book, which has possibly one of the best titles ever, In the Long Run We Are All Dead.

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Geoff.

Geoff Mann: Thanks a lot, Chuck.

CM: Joel, let’s start with you. You write, “For most of our lives, we have thought of climate change as a threat looming on the horizon, a challenge that would perhaps soon need to be faced. Those days are past. Today, all around the world the menace we worried about is no longer merely ‘potential’ but has rapidly materialized.”

Why isn’t climate change the top story of the news every night? If it’s already happening, it’s going to get a lot worse. If climate change has gotten so bad, how can we have so many people who simply believe it’s not happening?

JW: In a capitalist society, people intuitively recognize that to quickly confront climate change means decarbonizing the economy. Simply put, climate change is caused by changes to the atmosphere that come about when humans take things out of the Earth’s crust and burn them to power the economy—and put more CO² and CH⁴ in the atmosphere. At an intuitive level, when people figure out that’s the basic problem, this asks them to confront basic questions about how society is organized. And let’s be honest: in the political climate the world has been in since climate change was really discovered and became front page news, people’s political imaginations have not been broad enough or left enough to really imagine how we would go about quickly restructuring the world economy and political life to pull off any kind of transformation.

That’s a general answer. Here in the United States we have the additional problem of being the home of many of the world’s largest fossil fuel corporations, who (as is now well-documented and well-known) have spent an awful lot of money lobbying to change how people in the United States understand climate change.

It’s easy to get upset about denialism, and it’s entirely understandable, and correct to do so. It’s something we have to confront. But it’s also worth recalling that there are plenty of other societies in other parts of the world where we don’t have large fossil fuel companies funding denialism, but where we still haven’t seen high carbon taxes that would rein in fossil fuel use. It’s important to maintain a broader view, and this is where we have to pay attention to matters like capitalism and ideology.

CM: Geoff, to what extent do you think the fact that climate change’s first victims are the relatively poor and powerless leads to any under-reporting of climate change’s impact? Do we distance ourselves psychically somehow from climate change because the first people who are being affected are other people?

GM: It’s irrefutable. That the problem can be so great, as it already is, and affect literally millions of people, and be barely (if at all) mentioned in mainstream media and various other fora that we might come across in our everyday lives in these privileged part of the world where we live—it’s absolutely a function of not just its distance from but also its apparent irrelevance to our lives. I in no way mean to endorse the idea that it is irrelevant. But we are millions of miles from the lives of poor people in Africa and Southeast Asia, regions are already dealing with not just the signs of future troubles and terrors but already-existing massive effects of the ecological shifts that climate change is precipitating.

In my mind there’s no question that it exists. The fact that it’s the poor who are paying the price is one of the reasons that the rest of us can just cruise.

CM: Let me just follow up on that, Geoff, because you write in your book that climate change is having a toll on everyone. So how, right now, whether they realize it or not, are the rich and powerful already being affected?

GM: We could begin with things as straightforward as the ongoing drought in the southwestern US and Mexico; we could point to the shifting climate here in Canada, in the Arctic, and obviously in the American part of the Arctic as well. We could point to very obvious ways in which folks in Canada and the United States could run into the signs of a shifting climate every day.

Those things have inconveniencing effects on our every day lives (like when a big storm in Toronto ices up the roads), but they also have not just minor but really catastrophic effects on the lives of people who might otherwise appear kind of privileged to us—take the drought and wildfires in California this past summer .

We’re living in a dreamworld if we imagine those things are going to tone down, that that was “just a bad year.”

CM: So Joel, how impossible is it to stop using fossil fuels in order to mitigate climate change, and not have economic and political upheaval? Does climate change make that revolution inevitable?

JW: There’s a lot in that question, Chuck. Maybe we can parse it out in a couple bites. Let’s start with mitigation. For some time, the goal has been to reduce the amount of carbon we put in the atmosphere on the order of something like eighty percent or so, by the year 2050. That’s something you can find in the IPCC reports, or even in the aspirational statements that were made by the previous US president.

To actually bring that about, we have to change how we power the global economy. We have to move very quickly away from a carbon-based energy system. Let’s take a look at how we get our energy. If we look at the data from the International Energy Association (IEA), we can go back to around 1970 or so, when we started to have serious conversations about what green energy might look like: in those days, we already had a sense of what tidal power and solar power and dams and so forth could do; wind power has also been around for a long time. In those days, something like ten or fifteen percent of the world’s energy was supplied by so-called sustainable green energy of those types.

When we talk about mitigation, we’re talking about confronting not just a technical system of infrastructure but a political system which is global, and underlying both of them is the capitalist, growth-oriented form of our society.

Today it’s still more or less the same, although there has been a huge push for more renewable energy. It’s just that there’s a lot more energy produced and consumed in the form of fossil fuels around the world. Mitigation means qualitatively changing the whole global energy system.

There are a couple of big problems with that. One is that relatively speaking, fossil fuels are incredibly cheap as sources of energy, in part because we’ve been doing it for a long time so there are huge corporations that have a massive institutional framework, a global architecture for pulling the fuel out of the crust and burning it and delivering your electricity or the gasoline to your car. But on top of that there’s the whole political side of things, the political infrastructure, which includes massive subsidies for those corporations as well as the power system.

When we talk about mitigation, we’re talking about confronting not just a technical system of infrastructure but a political system which is global, and underlying both of them is the capitalist, growth-oriented form of our society. With that in mind, we can return to your question—can we quickly decarbonize the global economy without changing the basic form of our society? I don’t see how it’s possible, and I’ve never seen anyone produce a coherent explanation of how it could be done.

This is where most liberal thinking about climate change really goes out the window. We start to talk about if we painted our roofs white and drove less and biked more, we could chip away here and there. But there are a couple problems with that kind of thinking. One is how we manage to produce coordination globally to get a lot more people doing a lot of that stuff. Another is how we could prevent people who might free-ride in that arrangement from taking advantage of the extra-cheap energy that would be available, how we would stop states from subsidizing fossil fuels even more if people started to demand less of them.

This is where we have to consider serious political change. But exactly of what type? It’s not like there’s one clear alternative. In fact there are multiple different potential futures out there that involve addressing mitigation and adaptation. But unfortunately, both in the world of academic political theory and also on the political left, in the climate justice movement, we haven’t done a great job of being concrete and theoretically clear about what the different possible futures are that are available to us.

CM: Joel, let me follow up on that; I want to ask you about one potential future. You write, “The vast proportion of historical greenhouse gases have been emitted as byproducts of the choices and activities not of the masses of ordinary people but rather of a wealthy minority of the world’s people.”

So those who caused this are benefiting the most, and did nothing and continue to do nothing about it, as they’re still not affected while the poorest are. And they’re still benefiting from this system. How inevitable is any kind of class reckoning, in your opinion?

JW: First I want to make sure that we all remember, Chuck, that what you just said summarizes the huge moral dilemma at the heart of climate change which we can never repeat enough: we have a problem which is mainly affecting two enormous groups of people—the world’s poor and the future people of the world, almost all of them—who have done almost nothing to cause the problem. And conversely, the people who have done the most to cause the problem are by and large not going to feel the consequences of it.

As for the inevitability of conflict, I think I can speak for Geoff in saying that although we may be the kind of Marxists who think about long-term historical processes and capitalism and class conflict in ways that try to recognize the inevitability of conflict in a very general sense, we’re not the sort of people who think that any particular future is inevitable. That sort of thinking tends to lead the left in all sorts of bad directions: either we think we’re guaranteed to win because history is on our side, or we just throw our hands up because there’s nothing we can do, it doesn’t matter. Neither one of those outcomes is very helpful for either clear thinking or political organizing.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that anything can happen. There’s a kind of thinking which is really important: careful speculation based on clear premises, scientific reasoning, and historical analysis of what’s happened in the past. That’s the style of thinking we tried to inhabit when we were writing this book. When we occupy that style of thinking, our hypothesis essentially is that there are a couple more or less likely outcomes in the future, and the most likely one is the one that we named Climate Leviathan.

CM: That’s where I wanted to go next. Geoff, your book “outlines the potential political and economic paths we anticipate unfolding in a rapidly warming world. We examine the path we regard as most likely, which we call Climate Leviathan, and sketch the outline of the radical alternative.”

How bad can it get, Geoff? How bad could the Climate Leviathan be? “Climate Leviathan” sounds really bad. What do you mean by that term?

GM: Folks interested in the history of political thought will know right away that we’re riffing off the book by Thomas Hobbes from the seventeenth century called Leviathan. In that book, Hobbes famously makes an argument for what we might think of as a kind of absolute monarch. He says that the absolute monarch, to which all people of a territory are subject, is the one force that can suppress what Keynes would have called civil dissention. It makes civil war impossible. In the peace and stability that’s produced, people could live their lives pretty much like a proto-capitalist society. That’s what Hobbes imagined: a bourgeois republic under the shell of this absolute monarch.

When Joel and I are riffing on that kind of thinking, we’re proposing that the emergent order we think is most likely given the climate crisis is a global move towards a similar kind of power. The possibilities of that power are enormously complicated by the existing nation-state system and current geopolitical arrangements. Nonetheless we see a global desire for a power to come about that can mandate each one of us how much we can emit, who can emit, where they can emit, and create a stable, dependable, guaranteed, almost omnipotent carbon order that will therefore (hopefully, in this dreamworld) enable us to keep living the rest of our lives the way that we do now.

Both on abstract and metaphysical grounds, and also in terms of political arrangements, we could have something like the evolution of the political as such. We could have shifts like those during the birth of the modern era, when there were also ruptures in the political.

CM: Joel, you write, “Our point is not that global warming will simply cause everything to change or collapse. Instead we argue that under pressure from climate change the intensification of existing challenges to the extant global order will push existing forms of sovereignty towards one we call planetary.”

What do you mean by “planetary sovereignty”?

JW: It’s not the rightwing dystopian fantasy of world government…but it’s not completely unrelated, either. By planetary sovereignty, Geoff and I are trying to say two things at once. On the one hand we are trying to describe a form of sovereignty which is now planetary in scale. In that sense it’s breaking with modern political theory as it has been derived by Hobbes, in that we are finally somehow transcending a form of sovereignty that is specifically defined by a territory and its relationship with a given people. Not to say that sovereignty always works perfectly in the actual world or that there’s a coherent tie between territory and people—that’s a whole other discussion. But at least that’s how it’s imagined that it’s supposed to work. And in the future, we think that could be relaxed, and that there could be a form of sovereignty that could be defined by being planetary, that concerns people of the world as a whole and their management.

Which brings us to the second point, which is that under the modern compact which is supposedly underwriting modern popular democracy, the sovereign (which is typically defined as the people as a whole) legitimates rule, and the state or the government is supposed to defend the people, for instance through security and borders and all that stuff. Again, that’s the theory. I’m not saying that’s actually how it works or that it’s ideal.

But planetary sovereignty could define a scenario where life on Earth, both including human life and the viability of the Earth as a planet, becomes an ideological or hegemonic substitute for the notion of the people and their territory. Both on abstract and metaphysical grounds, and also in terms of political arrangements, we could have something like the evolution of the political as such. We could have shifts like those during the birth of the modern era, when there were also ruptures in the political.

That’s all pretty abstract, so let me add just one little qualification. Is this something that your ordinary bread-and-butter rightwinger in the United States would be afraid of? Most likely. They would define that as world government or a world state. When we hear that kind of rhetoric on the right, it’s not only quite vague, it’s also unclear what they’re proposing as an alternative. In our scheme, we touch on the desire to return to a kind of nativistic, religious or ethnic or racial order premised upon the secure defense of a particular in-group. We speak of that as Behemoth, in part as an homage to the classical opponent of Leviathan. And the reason we haven’t arrived at a world where we have a liberal Climate Leviathan already is precisely because of the persistence of Behemoths in different parts of the world which are holding back the emergence of this new form of political order.

So we don’t deny, at all, that there are counter-powers, so to speak, in the world. That’s why there’s nothing inevitable about Climate Leviathan. On the other hand, we don’t think all the Behemoths, as they exist now or will in the future, will have the capacity to produce a radically different order. At least that’s not what we see as the most likely outcome.

CM: Geoff, you write, “A stable concept of the political can only hold in a relatively stable world environment. When the world is in upheaval, so too are the definition and content of the realm of human life we call political. Political theory thus has a place in natural history, and finds its meaning through critical reflection upon it. Whether we know it or not, all of our thinking is environmental even when it rebels against nature.”

Last week we spoke with Emily Apter, author of the book Unexceptional Politics: On Obstruction, Impasse, and the Impolitic. Emily argues that everything is political, and it’s a mistake to think anything isn’t. Here you’re saying everything is environmental. Is everything, Geoff, both political and environmental? And with climate change, are the two now inseparable?

GM: That’s a fantastic question, and one that I’m somewhat wary of leaping into for fear of saying something that I’ll later regret. But I think it’s fair to say that at this moment in time (and perhaps this has always been so) there can be nothing environmental, as the term is conventionally used, that is not political in our world.

What Joel and I were trying to say in the passage you just read from is that our political thinking—in other words our understanding of what counts as political, the realm of what we think of as politics in contemporary life—is inevitably (if not entirely) environmental. It’s inseparable from it, if that makes sense. They’re not the same thing, necessarily.

But it’s important to try to frame what Joel and I are talking about when we say political, which may or may not be the same as what Emily referred to. At the most superficial level (without meaning her argument is superficial), Joel and I would immediately agree that everything is political, and if we think of things that are conventionally assigned to the realm of private life or intimacy and tell ourselves those aren’t political facets of life, we’re being naive. If that’s part of what she’s saying, then I think we would agree readily.

But Joel and I are particularly interested in the shifting ground of what counts as political life and political engagement. And insofar as the political has been heavily shaped by a notion of upheaval, as well as a distinct group of peoples coordinated territorially by something like the modern sovereign nation state—if those are among the crucial frames that contain political life, then we anticipate shifts, and would argue that it is already shifting. It is already being forced to confront environmental factors, primarily climate change.

All of our lives today are structured by the capitalist nation-state, which forms this world, capitalist modernity, which has a given set of political possibilities. It’s very hard for us to imagine that this could be otherwise. But when we look at things historically, it’s also obvious that this is a very recent, highly contingent, and by no means necessary relationship.

Climate Leviathan becomes an emergent global order that we see as a very distinct possible trajectory because climate change tests the nation state and our conventional understandings of the grounds of the political in ways that it has never been tested, perhaps ever. It demands a response that can’t be contained at any scale other than the planetary. When we have these meetings in Paris and Copenhagen, we see people who understand themselves as progressive and left all over the world desperately hoping for the coordination of a binding agreement, of a planetary power. This is the only way we can understand conventional political concepts to have any grasp in a future world in which climate has shifted things so much.

JW: In round numbers, human beings as a species have been on this planet for about three hundred thousand years. What we think of as the state—not the modern state, but the state as we may have found in the ancient Incan empire or the ancient Egyptian world—has been around for about ten thousand years. That means that in rough numbers, around 290,000 years, the vast majority of our time on Earth, humans didn’t have what we would think of as a state.

The modern state, which we think of as the capitalist nation-state, is even more recent, and emerges in human history just in the blink of an eye. What we think of as modern political theory associated with people like Hobbes or Machiavelli basically dates from the very recent period of the last two or three hundred years when the capitalist nation-state became dominant. All of our lives today are structured by this phenomenon, the capitalist nation-state, which forms this world, capitalist modernity, which has a given set of political possibilities.

It’s very hard for us to imagine that this could be otherwise. But when we look at things historically, it’s also obvious that this is a very recent, highly contingent, and by no means necessary relationship. In the most general sense, climate change presents us with a real crisis of the political imagination, because to really seriously think about how to confront climate change exposes the limits of our political imagination. That’s why we have to begin by realizing where we stand in terms of a longer arc of political history in light of the Earth’s natural history.

CM: Geoff, you quote another past guest on our show, Roy Scranton, author of Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, writing that “learning to die as a civilization means letting go of this particular way of life and its ideas of identity, freedom, success, and progress.”

We’ve been talking about how our political and economic systems have had an impact on leading to climate change, but how much are the ways we view identity, freedom, success, and progress to blame for climate change? Is it our views on and of identity, freedom, success, and progress that caused climate change?

GM: Those values, while certainly not at all unproblematic at the moment, didn’t emerge and exist independent of the capitalist liberal democracies that many of us live in today. Those values are themselves not independent ideas that the rest of society is organized around, but they’re actually materially produced by that world, and that means that as we struggle for a different world, we’re not necessarily going to be stuck with these rigid concepts that are somehow dragging us down like a sea anchor. Our political struggle will involve, hopefully, a really significant shift in our conceptions of what we value.

Effectively, Roy Scranton comes down on the side of a group of people who are increasingly vocal and increasingly influential, who understand climate change to be a kind of end game. There is a lot of talk about “We’re fucked.” Joel and I strongly want to resist that turn even though we understand, intellectually and emotionally, how people get there. We don’t think there’s no hope. We’re very concerned to focus on the people all over the world who (not at the scale of the state) are struggling incredibly productively in the worlds in which they live. And we need not only to endorse and support those movements, but we have to cultivate the possibilities of those movements in as many places as we can. We see enormous hope in indigenous struggle all over North and South America and the rest of the world. We see enormous hope in local efforts to shift the way that everyday lives are led.

We’re not fucked. We could be, but we’re not. There’s no guarantee. We see a great deal more possibility out there than perhaps the title of the book communicates.

CM: Joel, let’s follow up on that and the difficulty of hope. You write, “Rapid climate change is sure to have dreadful and often deadly consequences, particularly for the relatively weak and marginalized, both human and non-human. A political and ethical analysis is therefore of the utmost urgency.”

How difficult is it to make something the moral duty of society to address? After all, we have poverty, homelessness, and people dying because they can’t afford healthcare. So how hard will it be to make people realize the ethical urgency of addressing climate change? How much are we numb to the suffering of the world, so we are going to let the world suffer again?

JW: At the end of the movie that Al Gore made a number of years ago, where he tried to appeal to the American conscience to get them to pay attention to climate change, he used a World War Two metaphor, and he said we can do this, we can decarbonize our economy, because look at how we pulled together during World War Two when we needed to. I thought at the time that this is a really bad metaphor, for a lot of reasons I won’t get into now.

The challenge we face is unfortunately a lot more complex and difficult than that faced by the United State during World War Two. A better historical parallel would be the long human struggle to eliminate slavery. From the vantage point of slave owners, giving up slavery is impossible to imagine. It’s the basis of their livelihood and their power—and their identity. In a sense, for the wealthy of the western world, giving up fossil fuels in a form of society that has produced this incredibly injustice of climate change is an order which is just as tall.

It took humanity a long time to confront slavery. In the United States, to eliminate it took the bloodiest war in our history. We can and should question the extent to which we were ever able to do justice to that history. Obviously the struggle for racial equality and civil rights is very much with us today, and absolutely part of the agenda that we’re fighting for.

The order we have here is extremely tall, and it’s a huge challenge, but we can’t allow ourselves to be deluded into thinking that just because today someone comes out and says we passed the threshold and we now have 405 parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere, and the temperature in the Pacific has reached a threshold it’s never been at, and the world’s greatest, most powerful typhoon just hit a country, so therefore it’s all over—that sort of thinking is what we oppose. It’s quite possible that the future will have very serious climate change with a lot of dreadful effects, but if a left can become organized all over the world and change how we live, we could actually radically improve the lot of many, many people.

Conversely, we could have the emergence of a planetary sovereignty which essentially amounts to a collective management of life on Earth by some capitalist elites (principally the United States and China and a number of other powerful countries) where they mitigate some carbon and they allow for some very elaborate forms of adaptation but in actual fact life gets much worse for many people. What this means is that while all politics today is environmental in some fundamental way, it’s still politics, and we still have to maintain that struggle somehow.

CM: Geoff, does climate change guarantee the socialist revolution that conservatives have argued is the real motive of climate change activists? Are we now definitely going to have the socialist revolution all the socialists have been waiting for and all the conservatives have been fearing?

GM: No. It does not guarantee that at all. Of the various possibilities, that sounds like a pretty good one to me, but at present, without the kind of political work that Joel has been describing and that people all over the world are actually engaged in—without a lot more of that, something like a socialist revolution is highly unlikely. Something like a radically collective, redistributional, secure, and dignified politics for the people of the world could be an outcome of climate change—that’s definitely the work that needs to be done, but right now it is not at all likely.

That’s not to say it’s impossible. In fact it’s possible and maybe it’s more possible now than ever. Who knows?

CM: Geoff and Joel, thank you so much for being on our show.

GM and JW: Thank you.

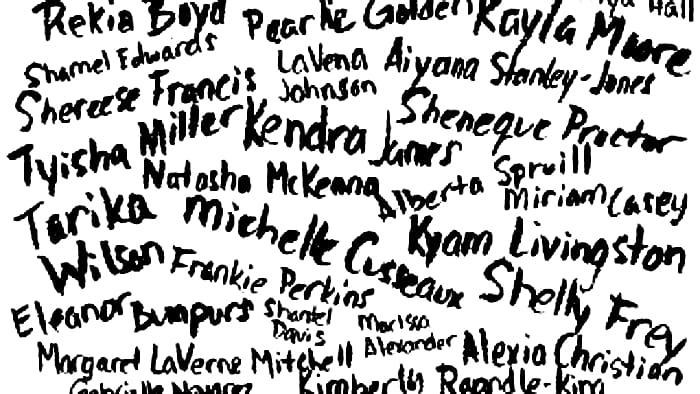

Featured image: artwork by Cai Guo-Qiang