Transcribed from the 16 March 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Women in Chile are finding feminism in their homes, in their jobs, in their schools—feminism is everywhere.

Chuck Mertz: Chilean feminism is challenging the macho establishment that has forever dominated the country, as well as the more recent neoliberal order, by going beyond mere intersectionalism towards strategies that are “multi-sectoral and transversal.”

Here to help us understand what that is so other activists may learn from the successes of Chilean feminism, American anarchist living and working in Santiago, Chile, Bree Busk has written the ROAR Magazine articles “Chile’s feminists inspire a new era of social struggle,” and “Chile’s feminist movement is here to stay,” which are two parts of an ongoing series Bree is writing on Chilean feminism at ROAR Magazine.

Bree is a member of both the Black Rose Anarchist Federation in the US and Solidaridad in Chile.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Bree.

Bree Busk: Hi, nice to be here with you.

CM: In your first article, “Chile’s feminists inspire a new era of social struggle,” you write, “It is May 2018, and as winter descends on Santiago, Chile, a new wave of feminist activity is exploding into life: antipatriachal graffiti covers the city’s walls, and streets are littered with the evidence of recent marches; tension is rising in the universities, and social media are flooded with posts ranging from cautious inquiries to joyous declarations. ‘Is the downtown campus of PUC occupied?’ asks one. ‘Was UCEN taken over?’ ‘Instituto Arcos on feminist strike!’”

Back in 2011 and going until 2013, there were major student demonstrations during what started as the August 2011 “Chilean Winter” protests, which led to the larger Chilean education conflict. Is the Chilean feminist movement of last year and now continuing into 2019—how much is this an outcome of the student protests from earlier this decade? Is this the legacy of those protests?

BB: That is a wonderful question. The answer is both yes and no. The students were definitely protagonists in 2018. The students have a long history of struggle. But in 2018, the students weren’t particularly active at the beginning of the year. It wasn’t a time where students were in a constant cycle of marches in the streets or making demands. It was actually kind of a quiet moment. The feminist movement intersected with the student movement, and the students had the muscle memory to pick it up and start running.

CM: What was the state of patriarchal power and the state of feminism before the current feminist movement? For people in our audience who are not familiar with Chilean culture or who haven’t visited Chile, what was the state of feminism before the current feminist movement?

BB: Chilean feminism goes all the way back. There’s a really wonderful, inspirational history going back to the turn of the previous century. But I would say this era started probably around 2013. That’s when issues like legalizing abortion rose to the top again here. Before 2017, Chile had one of the most restrictive anti-abortion laws in all of Latin America—no exceptions whatsoever, even in the case of rape and fetal inviability.

But also we have had growing tension around the issue of femicide, which is the targeting of women for violence and murder just because they are women or because they are not behaving the way that men expect women to. Often these femicides are carried out by boyfriends, husbands, exes, family members, or people in the community who don’t like to see women doing well for themselves or saying no. That topic has been in the news, in all the headlines, for years. And part of the more recent feminist movement has been focused on articulating that as a particular social and political issue, and organizing against it.

There are all these mixed issues—the abortion struggle, the struggle against gendered violence, and more recently, articulating economic issues through a feminist lens—and these are all cooking in the background, but nothing had quite spiked into a huge social movement in the streets until 2018.

CM: I don’t want to engage in tragedy porn, but I want to follow up on something you just said. How common is femicide in Chile?

BB: I don’t have the specifics in front of me, but let me put it this way: you hear something in the news every week. In fact, there were two femicides that took place in Chile and were reported and documented just the day before the march. I’m sure the outrage around that really put the fire to people’s feet to jump up and participate in that moment.

CM: One of the things I’m concerned about is an oversimplification of the feminist movement in Chile—if it even gets reported here in the US media, I’m concerned that it’s going to be reported as a march or a movement for reproductive rights and that’s it.

What is missed when we only see the feminist movement in Chile as a fight for reproductive rights?

BB: Almost all of it. That is an important pillar, but I don’t think it’s been the motivating factor in the most recent years. It’s there, but I think that growing inequality is more of a motivator. When we talk about gendered violence, of course we can talk about femicide and domestic abuse, but we’re also talking about the violence of capitalism.

Chile, to the outside world—especially to the Latin American region where it is—is doing really well economically compared to others. There are a lot of economic migrants who come to Chile for that reason. It’s considered a stable, good country where people can make it. But at the same time, much like the US, there is an increasing gap between rich and poor, and women are even further disadvantaged under that system.

In a way, the left establishment can be just as obstinate as rightwing establishment parties. People who have been in power for a long time don’t like being told they have to do things differently or think of things that they didn’t consider before. There’s a good portion of the left in Chile who are very comfortable.

For example, with our pension system you only accumulate money towards your pension when you’re working. What about the many Chilean women who are working in the home, as housewives, caregivers, or working in the informal economy? It’s probably more the rule than the exception to be working without a stable contracted job.

So women are finding feminism in their homes, in their jobs, in their schools—we could talk about sexist educational policies: the lack of sex education, the lack of protocols to protect students from abuse in their educational institutions. Feminism is everywhere. That’s one thing that people need to see about this movement right now.

CM: In 2013, Chile did elect Michelle Bachelet as president. Did that in any way have an impact on the feminist movement? Here in the States, when Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, all of the sudden people were saying we were living in a post-racial society (which was definitely not the case). I’m wondering if there was the same kind of exaggeration in Chile, that they were somehow living in a “post-sexist” Chile because Michelle Bachelet had become president.

Did her election have an impact on the feminist movement in Chile?

BB: I wasn’t here for the period when she was in power, but you are not the first person who I’ve heard make this connection between Bachelet and Obama. They both represented a lot of hope, because they were coming from a progressive type of messaging, and in a way Bachelet did make some concrete improvements that women benefited from. But like with Obama, by the time she was finishing her second term, people were very disillusioned with what she could accomplish. She was in power for a lot of the high points of the student movement, and I think the students might have felt that she was going to be an asset to their struggle—and there were some accomplishments achieved, but we don’t have free education in Chile.

Just having a woman or even a socialist as president was not enough to achieve the major goals of the movement.

CM: You mention how the feminist movement in Chile is disrupting and challenging the left as a whole. How do feminists disrupt and challenge the left?

BB: That was something I saw a lot of in the period right before 2018. Towards the end of 2015 and 2016, feminism was on the table, and all the traditional leftist groups—both the official parties that run candidates in elections and also the smaller political groups or social movement organizations—had to think about what to do with this now that they couldn’t avoid it.

Some political groups decided to avoid it, and a lot of them paid consequences for that—losing female membership, having terrible splits; other groups just dissolved under the pressure. Others were able to integrate the new critiques and issues that were being presented. In a way, the left establishment can be just as obstinate as rightwing establishment parties. People who have been in power for a long time don’t like being told they have to do things differently or think of things that they didn’t consider before. There’s a good portion of the left in Chile who are very comfortable. Suddenly people who were used to assuming that male leadership is the default were being forced to accept changes.

Some feminists might just want to see it all burn; others are in the trenches trying to force change in their respective organizations or movements to make them feminist.

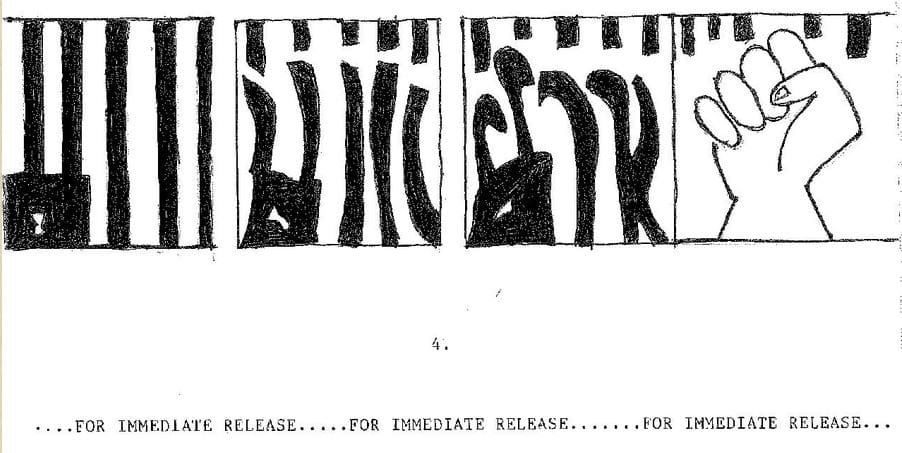

CM: You write, “The Chilean student movement has a long, rich history, most recently marked by periods of struggle in 2006 and from 2011-2013, and can seem quite exotic to foreign audiences thanks to iconic photos of occupied schools and massive mobilizations. However, there is a danger in romanticizing these superficial images of struggle. The risk is that without historical grounding or contextual analysis, this current spectacle of youthful feminist rebellion will obscure the far more intriguing political developments taking place away from the cameras.”

What are those developments that are taking place away from the cameras?

BB: One of the most interesting topics right now is in regards to the immigrant movement here which is just beginning to come into being. Chile traditionally hasn’t counted on a lot of immigration. It’s a very isolated country with an ocean to the west, the Andes to the east, the Atacama desert to the north, and Patagonia to the south. But, like all countries, when Chile became more stable and more economically advanced than its neighbors, it started to attract more and more people.

Right now, we have a huge number of Venezuelans entering the country. We also have a lot of immigrants from Haiti. They represent a really interesting new challenge for Chile, because there wasn’t a large established black population in Chile before. In a way, Chileans are having to develop their racial consciousness at the same time that they’re learning what it means to be a country that attracts immigrants in massive numbers. Of course the product has been a lot of xenophobia, and there’s developing anti-black racism as well. Some people are becoming more conservative.

However, something really inspirational is that one of the first groups that said we need to deal with racism and deal with anti-immigrant sentiment was the feminist movement, even before it was reaching the peaks that it has today. For example, on International Working Women’s Day, March 8 of the year before last, I remember attending basically a propaganda-making event where everyone translated all of the slogans of the march into Haitian Creole and put them all around the city, with messages saying, “Women immigrants, we welcome you to the struggle.” And it’s not just in the messaging, but it’s trying to do concrete outreach and support. Because women migrants are in a position of hypervulnerability. Some don’t know Spanish. Some don’t have legal status. Some will be victims of femicide, state violence.

The feminist tendency intersecting with the immigrant movement is something that definitely deserves more attention.

Fascists don’t necessarily expect to win, but they use elections as a method to get their message out there, to create a higher visibility for their type of politics.Their movement is growing. But I think the feminist movement is growing faster and it’s better organized.

CM: You write, “In late 2017, the struggle against femicide and gendered violence converged with the immigrant rights movement with the death of Joane Florvil, a young Haitian woman accused of abandoning her infant daughter. Joanne was subsequently arrested and held in detention until her death thirty days later, allegedly due to injuries that occurred during her arrest. As a recent migrant who didn’t speak Spanish, Joanne was placed in a position of hypervulnerability, unable to explain her actions to police or to defend herself against their accusations. Her death has since become emblematic of growing xenophobia, a problem which is further exacerbated by anti-black racism and misogyny.”

So: anti-black racism, misogyny, anti-immigrant sentiment—does any of this reflect a growing far right that is increasingly violent in Chile under neoliberalism, as is being seen in other neoliberal democracies? Are you seeing a rise of the far right in Chile?

BB: The short answer is yes. It’s manifesting in a lot of different ways. First of all, fascism never really went away here. The deal that the institutional left made when democracy returned to Chile was that a lot of people were not going to get put in jail for their participation in the dictatorship. Which means there are people in congress right now who are Pinochetistas. Openly. Without shame. There are still monuments to fascist ideologues up in the city, in public places. In a way, the history of the far right and fascism here is an unbroken part of the chain coming from the dictatorship.

But we’ve also seen some new developments. For example, in the last presidential elections we had a fascist candidate named José Antonio Kast, and people in the US would recognize him as a familiar type of public figure. He gave the Steve Bannon feel, where he won’t say exactly what he’s for, but he knows how to dog-whistle with the best of them. He represents the politer institutional face of what is really a violent, growing rightwing movement.

We also have a lot of smaller grassroots fascist organizations that organize under slogans like “Neither the right nor the left!” (which always means the right, incidentally) or “We’re just patriots; we don’t care who you are, we just want traditional values” (which for them means being anti-abortion, anti-feminist, and anti-migrant, and under anti-migrant slogans they also mean anti-black). Those groups have been increasing their media presence, getting more interviews. I see their graffiti going up around the city, and also their posters and propaganda.

The worst example that we saw was last year during the annual march to expand abortion rights. One particular group came and tried to do a propaganda action to disrupt the march, tried to drag some barricades into the street. They had a big banner that said something like “Female animals should be sterilized” (meaning, of course, feminists). They had buckets of blood and animal viscera that they dumped on the march route. Of course, though that was disruptive enough, it didn’t stop things. But there was a group of hooded, masked individuals who then attacked the march in different sections simultaneously, stabbing some of the women who were participating in the march. No one was caught for that crime. And of course the group denies carrying out that attack, but they did it.

CM: You mentioned José Antonio Kast, and you write in your article that his “2017 presidential campaign promised a return to law and order and was welcomed by traditional conservatives. His hardline positions on immigration and social issues such as abortion made him an inspirational figure to fascist groups organizing on the grassroots level. The ascent of nationalist and ethno-supremacist movements globally has given Chilean fascists a feeling of increased legitimacy, and the threat of organized violence against black migrants and feminists is moving from empty posturing to real violence on the street.”

But Kast came in fourth place in the first round of 2017’s presidential election, was not able to make it to the runoff, and he got less than eight percent of the vote. So how representative is Kast of Chile? Or is his popularity growing since his 2017 electoral defeat?

BB: Not everyone would support him. Piñera is a much easier candidate to get behind, even for more extreme conservatives, because his main angle is that he is a businessman; he would rather ignore the feminist movement into nonexistence, to rebrand it, to de-escalate it, to use softer tactics. But something we’ve seen in the US is that fascists don’t necessarily expect to win, but they can use elections as a method to get their message out there, to create a higher visibility for their type of politics.

Kast is not the only politician with that type of angle. The movement is growing. But I think the feminist movement is growing faster and it’s better organized. Whenever rightwing extremist groups try to do their own actions, they are inevitably much smaller, much weaker, and focused on trying to gain media attention more than posing an actual counter to the movements of the left right now.

But things can change quickly, as they did in the US. We had a candidate who was a joke for many years, and now he is our president. Chileans believe that the tide can turn quickly.

CM: Is feminism in Chile leading to a decline in fascism? Is feminism actually undermining fascism? I saw a poll saying that 75% of Chileans support the feminist movement. So is it really having a big impact as far as antifascism is concerned?

BB: I don’t know if it’s undermining it. But fascists can’t organize without thinking about the feminist movement. Where is the army to fight the rise of fascism? The feminist movement is the army we have. Not just in Chile, but in Brazil, and even in the US eventually. But I’m not ready to make an assessment of that, because people are still operating with a certain degree of caution.

A lot of the feminist leaders—the people you see on TV all the time—are going around with security details. There are still isolated attacks. But I haven’t seen a fascist march in quite some time either. Also similar to the US, those types of groups have their own internal power struggles and tear themselves apart.

There was a small action done a week before the March 8 strike, where a little teeny group identified as rightwing libertarians tried to do a counter-propaganda activity. It was so small that it was erased by the flood of media attention to the feminist activities that were happening at the same time.

CM: You mention the multi-sectoral and transversal tendencies within the feminist movement in Chile, which “arguably hold the potential to unite Chile’s diverse social movements into a force capable of presenting a real challenge to the triad of capitalism, patriarchy, and the state,” as well as the emergence of La Coordinadora 8 de Marzo, or C8M, the coalition serving as the primary vehicle for this political approach.”

You’re not seeing only intersectional, but multi-sectoral and transversal tendencies within the movement. Is this more than intersectional? What do you mean by “multi-sectoral and transversal?”

This feminist movement is not a movement of bosses and politicians. This is a movement of women who are working class, indigenous, people who do not have access to institutional power to enact their demands. They have access to popular power; they have access to each other.

BB: Multi-sectoralism is the idea of mobilizing different sectors or areas of struggle around common demands. Example sectors could be healthcare, the student movement, the labor movement, or the territorial movement—the movement of communities, land, territories, housing. A multi-sectoral movement is the idea that movements shouldn’t just stay in their lane, that we need an analysis that incorporates all of these different areas, and then find something to bind them together. There could be students supporting labor demands, or workers supporting the demand for dignified housing. The idea is to get everyone on the same page, working together through networks of mutual support, so no issue is left behind, and no issue stands in isolation.

For example, there is an organization that would translate as the Healthcare for All movement—they are a multi-sectoral organization in that they bring together medical professionals, patients, and medical students, and try to do healthcare work that touches on all these other areas. When there was an indigenous hunger striker who was carrying out a hunger strike in order to access the right to his religious ceremonies, the healthcare organization mobilized around supporting him, from a healthcare perspective: that he deserves his treatment, he deserves to be free to live his life and to practice his culture and religion. They also organized trainings: medical students would do free workshops, medical trainings, and offer basic services in their neighborhoods or in the neighborhood where their university is located. It’s uniting students with healthcare with neighborhood organizing. That’s the idea, it’s things mixing together and mutually reinforcing each other.

The transversal element is finding the things that can actually bring these sectors together. For example, transversal feminism: feminism is not a sector. Feminism is something that exists in all areas. There is feminism in the workplace. If your boss is harassing you, you need feminism there. You need feminism in the home, where maybe a wife or a mother is forced to take care of all the domestic duties with no support from her partner. You need feminism in healthcare, absolutely.

It is intersectional, but it’s more than intersectional. The power of feminism right now is that it can be a uniting tool to make people understand how their struggles are related. We are much more powerful when we are fighting together and learning from each other than we are if we stick to our little pet cause or only work with what’s in front of us instead of working from a systemic analysis.

CM: You also mention the power of empathy rather than employing sympathy. Why do you see more power in empathy, when it comes to Chilean feminism, than you do with sympathy?

BB: Sympathy comes from an idea of charity, of feeling bad for someone who is experiencing something that you are not experiencing. It’s true that each of us does have a unique existence—there’s no such thing as the universal experience of being a woman. But we can still find common themes. The theme of violence is one that women all over the world can find empathy with. To different degrees, absolutely. But individual and structural violence is part of women’s reality.

Also, we can empathize around our relationships to power. This feminist movement is not a movement of bosses and politicians. This is a movement of women who are working class, indigenous, people who do not have access to institutional power to enact their demands. They have access to popular power; they have access to each other. When we understand and can identify the threads that build empathy between us as individuals and as a movement, that gives us a starting point to start overcoming these systems that oppress and exploit us.

CM: You mention sexual dissidence, a “radical answer to the neoliberal politics of inclusion and diversity, popularized by such groups as Sexual Dissidence University Collective. Sexual dissidence denotes constant resistance to the prevailing sexual system, to its economic hegemony and its post-colonial logic, and rejects the idea of subversive identities (gay, lesbian, queer, trans, drag, etc.) in favor of subversive analysis and action. The result is an inclusive, combative politics that cannot be easily co-opted or institutionalized no matter how many individuals are peeled away by token reforms.”

How does sexual dissidence bring about a larger revolution than something only centered on identity? And do you believe rejecting the idea of these subversive identities (gay, lesbian, queer, trans, drag, etc.) would cause more participation by more people in a feminist movement today here in the States?

BB: Something like sexual dissidence does exist in the US, in the queer liberation tendency, in the anti-assimilationist queer positioning—the idea that being a rich gay real estate broker is a different experience, materially, than being a poor trans woman sex worker. That analysis is there in the US. Here, the strength is that it’s not rooted in who you are but in your relationship to power. That is a much more potent area to organize from.

The group that you mentioned, CUDS, says that for them sexual dissidence is important because any identity can be co-opted. Being gay, for example, is not enough to ensure that you will maintain a counterposed perspective towards systems of power. You can be assimilated, you can participate in this structure. The idea is to have a way of acting that can’t be assimilated.

That doesn’t mean that people don’t get to identify as gay, as lesbian, as trans, as non-binary. All of that exists here. In a way, the integration of these communities into feminism here is more successful than it is in the US because it’s around an analysis of power.

There’s the same idea with feminism itself. Just being a woman doesn’t make you a feminist. It’s what you do, it’s how you act, it’s how you relate.

CM: You write, “United under the banners of non-sexist education and an end to patriarchal violence, Santiago-based high school and university students mobilized on May 16 of last year in the largest feminist mobilization in Chilean history, initiated by the Chilean Student Federation. This march caught the world’s eye with its flashy contingents of young women marching topless while wearing maroon balaclavas, a choice that was as much a demonstration of power as a celebration of bodily autonomy.”

Why topless? Why do you think that topless is a good strategy for a feminist mobilization?

BB: It’s one strategy. For young women who are participating in the movement today, the idea of showing your body because you want to, not as a spectacle or for the sexual consumption of others, but to simply exist and be surrounded by your classmates, by your friends, and to feel the power of that in numbers, and that protection, and to say that your bodies have other purposes, your bodies can be for the fight, for the struggle, and not just for titillation or entertainment or for selling products. Women who use that tactic want to rebrand their bodies, in a way, to take back how they’re defined, and put them in their own context. In a way, more than being attractive, women who do that tactic are a little scary. I think that’s pretty cool. And I’m sure that’s one of their goals.

CM: Bree, I really appreciate you being on the show.

BB: Thank you.