Transcribed from the 30 July 2025 episode of Syria: The Inconvenient Revolution and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole conversation:

Islamized Armenians want to connect with the global Armenian community. One of their arguments is: “We’re a resource. We’re Muslim, we’re Kurdish speakers, we’re Arabic speakers, we have a unique position, and we can bridge these cultures.”

Leila Al-Shami: Hello everyone, welcome to another episode of Syria: The Inconvenient Revolution. I’m your host Leila, and today I have with me Dr. Karena Avedissian, who some of you will know already because she’s another member of the From The Periphery collective and the host of our podcast called Obscuristan.

Karena has recently returned from a trip to northeast Syria, where she was doing research into the Armenian community there (she’s Armenian herself)—these are survivors of the Armenian genocide. She wrote a fascinating article about Armenians who had become Islamized, which was something I knew very little about before.

Very happy to have you with us, Karena, please introduce yourself.

Karena Avedissian: Thank you Leila. I’m Karena. I’m a political scientist; previously I have focused on social movement mobilization, and more recently on disinformation in Eurasia. I focus on Russia, Armenia, and most recently I conducted a research visit to northeast Syria where I spoke to Armenians, and it turns out there are lots of Islamized Armenians in the region.

LS: How many Armenians are in northeast Syria, and can you tell us a bit about how they got there?

KA: As anyone who has cursory knowledge of the Armenian genocide knows, when the massacres started in 1915 it was followed by a policy of forcibly deporting Armenians to the Syrian desert. We know that many of the survivors of this deportation were small children and that they were adopted into local Arab and Kurdish families. Somehow after that the story ends and these people disappear.

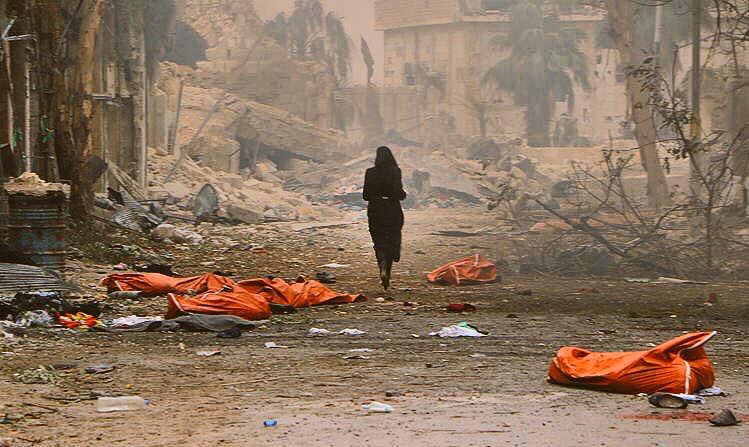

When I went there, I was quite shocked to understand that more than twenty thousand Islamized Armenians live in the region. These are descendants of the Armenian genocide; they had gone through a network of what were essentially death camps—which later, by the way, became a model for Hitler’s plans in Nazi Germany. These were camps that were established in numerous locations, particularly in al-Bab, Manbij, Maskanah, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, Ras al-Ayn, and other places. In Deir ez-Zor in particular, until recently, people who visited would take videos and photos of themselves sweeping aside dirt in random areas and finding bones everywhere. That’s how many were killed there.

The official number of victims of the Armenian genocide is 1.5 million, and we know that 800,000 to 1.2 million Armenians were forcibly deported to the Syrian desert. So it was actually a main theater of the Armenian genocide—which was something quite new to me, thinking of it in that lens, because I’d always focused on Anatolia.

There are Christian Armenians as well in Qamishli, which is the more traditional Armenian community. But the Islamized Armenians were invisible under Assad, because Assad dealt with the Armenian community in Syria through the Armenian church. And because the church didn’t recognize them, neither did Damascus. It was not until the Rojava revolution and the establishment of the Autonomous Administration in 2014 when the space opened up for different ethnic groups, including these Armenians, to assert their identity and establish their own institutions.

LS: That’s very interesting. They’d been totally invisible until now. Could you tell us about some of the challenges they are facing in reclaiming their identity and connecting to their heritage?

KA: First it’s just assimilation, just a natural process. Four or five, and in some cases six, generations after Islamization, they don’t speak Armenian anymore and they haven’t in any measurable way grown up in the Armenian culture. They’ve been completely separated, isolated from all the narratives and discourses that have been happening in the Armenian transnational community. In Syria, Aleppo has a big Armenian community, Qamishli has an Armenian community, there are schools there—and they were part of this world, they were part of the discourse network, meaning-making and identity-building post-genocide. This group of people was completely cut off from that.

I’ve heard lots of other Armenians say, How Armenian are they really? They didn’t grow up Armenian. But certain markers I found quite interesting and unexpected. In visiting with these people and speaking with them, I was astonished to learn that many of them are one hundred percent Armenian—I don’t like to give percentages to ethnicity, but they had continued marrying among one another even as they were Islamized after a few generations. They quietly preserved the knowledge of who in the community was Armenian.

Some described grandfathers, great-grandfathers warning their children not to be public about being Armenian, not to announce it. When I asked why, they said it was partly fear: they were traumatized from the genocide. Even the next generation was still living with that fear: If we tell people we’re Armenian they might kill us. Some of these Armenians grew up in really rural, tribal areas where being open about a different identity was looked down upon, so depending on the tribe that they were with, it was like they already knew being Armenian wasn’t good, so it was best not to be open about it.

Others still said that, No, our grandparents were proud to say they were Armenian! They would talk about the positive stereotype that Armenians are “industrious” and would be open about that. This is also interesting: some of the adoptive families, the parents, made sure their adopted Armenian children would marry other Armenians. They would do the marriage match-making and find other Armenians that had been adopted by other Arab or Kurdish families, and marry those children together.

There are so many definitions of ethnic identity. One is internal; the other is external, where the community around you identifies you and sees you as Armenian (or whatever the ethnic group is). One internal marker of identity that I think is important—I’ve just finished transcribing my interviews and am just starting to make sense of what they had been telling me. In multiple interviews I conducted with Islamized Armenians there is a sense of historic continuity, the memory of genocide—even though many of them are descended from orphans who were barely three and don’t know where they came from in the Ottoman empire. But they knew stories.

Again, a lot of times these stories, this collective memory or memory work, was also done by the community outside of them. For example, one man I spoke to, who was maybe in his sixties, a Kurdicized Armenian from Ras al-Ayn (who ended up displaced in Tal Tamer because of SNA violence, Turkish-backed militias), spoke of his ancestor, his grandfather or great-grandfather, who ended up in the Syrian desert, in Ras al-Ayn, and the family didn’t know where he came from. They asked around to neighbors—Can you tell us where he was from?—and some of them would say, We know by the clothes he was wearing that he was from Sasun in the Ottoman empire. Based on those stories and that memory, they could figure out where their ancestors came from.

Other themes I noticed were the trauma of the genocide and the memory of that seemingly haunting many of my respondents—again, generations later.

LS: You had a very powerful story in the text you wrote, a story of cannibalism and how that had impacted people many years later. Maybe you can share it with us.

KA: I had a wonderful Kurdish translator; she was a young woman from Afrin. This is interesting because as a woman from Afrin she was also displaced; she was based in Aleppo. When I had gotten in contact with her, she made the trip from Aleppo to the Autonomous Administration to help me with these interviews. She said she was very interested in Armenian history, so she was quite happy to accompany me on these interviews.

During one interview we sat with a Kurdicized Armenian woman, and our interview hadn’t even begun—we were drinking tea in the evening and just chatting—and the translator was translating what the woman was saying in a relaxed way. Not everything, it wasn’t a formal interview yet. And I realize at one point my translator is crying, and I look at my respondent and she’s wiping away tears and continuing to speak. I’m understanding that something heavy is being discussed.

I looked at my Kurdish translator expecting the translation, and she looked at me and said, How can I translate this? I can’t do it. I was like, Can you just give me an idea? You can be vague about it. And she said, I’m human—you hear all these horror stories about genocide and you know about the death, the violence, but sometimes it’s just too much. She really didn’t want to tell me.

After some nudging, she galloped through what she had been told. She didn’t give me any of the emotional detail that was eliciting such an emotional response from both of them. She said, There was a boy, I don’t know if he was dead or alive, but they cooked him and they ate him. It was a moment of understanding that there was an act of cannibalism—which makes sense. They were on death marches in the desert; they didn’t have food or water for weeks. And yet it’s not one of those stories that gets passed down very often. It made me think about shame, and how shame and trauma shape identity and reinforce it in ways that obviously continue to reverberate many generations later.

It felt as though—we can talk about the political project of the Autonomous Administration, but their identities were so political, and I was impressed by the way they would speak about their work in the Autonomous Administration, establishing councils and brigades. This woman, for example, was the head of the Armenian Social Council based in Hasakah.

Turkey is our main enemy is something I heard over and over again from Armenians in the region, and from others as well—and it’s the same Turkey we’re dealing with. They didn’t finish the job and we shouldn’t get lulled into a false sense of security that the genocide is over. The fall of Artsakh was mentioned very much: See what happened? It just keeps happening! So we need to be prepared, we need to be organized, because they tried to annihilate us.

I mentioned in the article I was reminded of Talaat Pasha’s words. He’s one of the three architects of the genocide, and there’s a famous line attributed to him where he says about the Armenians, “They can live in the desert but nowhere else.” And here I was finding this community of Armenians living in the desert, still holding onto their identity, and now, in this context and political environment, given the opportunity to assert their identity and reclaim it.

LS: The Autonomous Administration has been lauded for its attempts to create a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society which could act as a model for Syria as a whole. Maybe you could tell us about some of the steps it’s been taking to include people, and the structures that have been set up to achieve those aims.

KA: The Autonomous Administration, after it was established in 2014, established a social contract which acted effectively as a constitution. If you read the language of it, it’s very explicit about its multi-ethnic, multi-confessional society; that is a defining factor and a strength of it. The Islamized Armenians’ experience establishing themselves is a really good example of how this works.

When the Autonomous Administration was established, it was a Kurdish-led coalition of Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Syriacs, and other groups. Essentially the Kurds were ahead in terms of the self-organization, the political structure, and the ideology to make this happen, and then the Arabs followed—this is what people tell me—and then it was the Syriacs. The Islamized Armenians were smaller in number, they were scattered around, and under the Assads there was no sense of a unified, cohesive community for them, but when it came time for them to be able to do something, it was that structure, that freedom by which different ethnic groups can establish their own political parties and institutions. In the Armenians’ case it’s the Armenian Social Council, the Armenian Women’s Union, and the Martyr Nubar Ozanyan Brigade, the self-defense unit.

It’s not a perfect model at all. In fact, I hear a lot—I haven’t seen evidence of it, but there is apparently low-level corruption that the administration turns a blind eye to, because as long as it doesn’t threaten the governance of the leadership or the project as a whole, it’s left alone. Sometimes I think, Is that just an inherent aspect of systems that are really decentralized? How do you clean up certain institutions? Is it individuals? I don’t know the answer to this question. But they were given the space. As long as they had enough people registering, they were able to establish their own political parties and their own institutions.

I asked someone recently about the Assyrians, because they’re larger in number than Armenians in the region, and specifically about language instruction. Post-revolution, now the curriculum in the schools of the Autonomous Administration teach Arabic and Kurdish, whereas before it was just Arabic. And apparently all ethnic groups technically have the right to establish their own schools with their own language instruction. But in the Assyrians’ case, many left post-ISIS violence. This is something that’s very little-known and very little talked about: the whole Tal Tamer river valley was inhabited by Assyrians, and they’re mostly gone and haven’t returned. Their homes are still standing, they still technically own these homes, but they’re gone. So there’s so few Assyrians that there’s no language instruction.

Another researcher who was recently in the region, a friend of mine, was talking about the Syriacs: they also had their own language instruction but they didn’t opt for that. Maybe it wasn’t useful to them or they didn’t feel like they needed it. They only have Arabic and Kurdish language instruction.

LS: The Armenians in northeast Syria either speak Kurmanji (the local Kurdish language) or Arabic. Are there attempts, then, to revive Armenian? Is there interest in that? We hear about Kurdish communities that were Arabized, but what we don’t hear about is communities that were Kurdicized or Islamized—what are the steps that are being taken to revive their linguistic heritage?

KA: The Armenian Council has been offering language instruction in western Armenian. There are two main dialects of Armenian: eastern is spoken in the Republic of Armenia and Iran, and western Armenian was spoken in the Ottoman empire. The descendants of genocide survivors took western Armenian with them to Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere. What I know about language learning is that you best learn a language when you need it to meet your needs—like as a child, for example. And it’s not needed, especially in Hasakah, which is the hub for Islamized Armenians.

I walked into the council room one day during language instruction, and there was a young man who I became friends with, a young Armenian man from Aleppo—his parents had died, he told me he didn’t really have anyone left in Aleppo anyway, so he wanted to come fulfill this “patriotic” (as he said) mission to teach Armenians Armenian. When I walked in, he’s at the whiteboard with Islamized Armenians sitting around, one has a child on her lap, literally learning the conjugation for “I’m learning Armenian, you’re learning Armenian, he/she is learning Armenian.” And another language instructor was expressing frustration: You teach them something and it goes in one ear and out the other, they leave and go back to their Arabic-speaking homes, and they come back having forgotten the previous lesson and you’ve got to start over.

It’s an uphill battle. Resources are hard to come by in general in the Autonomous Administration; Turkey has cut off a lot of major water supply, everything runs on diesel generators. Asking an Armenian from Aleppo to come and make that move is quite a big ask. It’s still early days, relatively speaking—maybe they get more resources moving forward. But none of them spoke with passing fluency, which I found interesting. They all knew “Hello, good morning,” and “would you like…?” giving me a coffee or whatever. But they didn’t really speak it.

I’m self-conscious in general, but there was a cute self-conscious excitement that This Armenian from Armenia has come, and she’s come to speak to us because we’re Armenian! It felt like a sense of validation for them, and that really meant a lot. During one event, a genocide commemoration on the eve of the actual commemoration day, a candle-lit march, someone tapped me on the shoulder and I turned around and this person was like, There’s ethnic Armenian soldiers here to say hello! They heard there was an Armenian from Armenia and they just want to say hello. And there are twelve young men just standing there smiling. I was like, Hi, can I take a photo? They said yes and I took a photo of them.

It’s a connection that I think means a lot.

LS: These Islamized Armenians face some kind of exclusion or even discrimination within the broader Armenian community in northeast Syria. You tell a very sad story in your article about some Armenian fighters who died defending an Assyrian church, but their mothers are not allowed to enter that church to mourn them because they are Muslim.

What is their relationship like with the broader Muslim community, then, with Kurds and Arabs in the region who are Muslim? Is there a sense of brotherhood between them, or not?

KA: It’s an interesting question. I felt like I couldn’t access that world, being on the outside. Most of them seemed quite secular, even the ones in headscarves. It wasn’t a forefront issue for them. One told me, without me asking, Sometimes I get pushback, “How can you continue to be Muslim? We understand you were assimilated and were Islamized, but why not convert back?” And she was pre-empting me asking that question by saying, I don’t see any contradiction in being Armenian and Muslim. It’s a religion of peace, and I don’t see a problem with that.

Indeed, this is a mirror of Islamized Armenians in Turkey, where Armenians who remain—there are more than people expect. When you read the scholarship on it, you find there are many more Armenians who stayed and survived and had to hide their identity in Turkey than you would think. And a man I spoke to in Turkey said the same thing: It’s not an issue.

But actually it’s a good question in terms of what they represent for the Armenian community. On the one hand, Armenian identity is generally defined in quite rigid ways (although with younger generations that’s changing): for older generations, being Armenian means being Christian. There are historical-social reasons for it, one of which is Armenians didn’t have a state for thousands of years, and it was the church that managed the community, and mediated relations between empires and communities, and states and communities.

That’s on the one hand, but on the other, these Islamized Armenians—more than anything, they want to connect with the global Armenian community. One of their arguments was, We’re a resource. We’re Muslim, we’re Kurdish speakers, we’re Arabic speakers, and we have a really unique position and we can provide that bridging of these cultures. Especially at this juncture of Armenian history, which I won’t get into—currently the Armenian nation, transnationally, is going through some hard times after the loss of Artsakh, continued aggression from Azerbaijan, and pressure from Turkey. Armenia is not in a good place right now, and they know this. Their argument is, Let us be a part, let us increase your numbers, let us help.

That’s the most “relevant” way that religion came into it—as a resource.

LS: Did you feel like Armenians there were trying to reach out and connect to Armenians elsewhere? Are there those openings and those channels?

KA: No. Not currently. Given their political context and the historical one—they’re excluded from the Armenian community in Qamishli, let alone trying to conjure up the resources it would take to travel to Armenia. A lot of these people don’t have passports, especially now. Everyone is waiting to see what will happen in the negotiations with Damascus regarding the status of the Autonomous Administration, whether it’s going to be integrated or retain some level of autonomy. It’s a big question, and it’s something they worry about.

There’s essentially no connections. When I was interviewing people, I would ask them: Okay, I am a diaspora Armenian, I’m here—but how many others have come?And they would say, It’s you and this one other guy—who’s my friend! It’s a close circle of people I know, and no others. It’s partly due to the perception of Syria as being a dangerous place, or that travel there isn’t easy, especially if you go through Iraqi Kurdistan. It’s quite a journey and not without stress (to put it mildly).

So there’s really virtually nothing yet. It feels like if there’s an opening they should be in a position to reach out and do something.

LS: Did you face pushback and restrictions in doing your research? You tell a story about a discussion with a priest that you could get into, but I was wondering, why is it so sensitive to tell this story?

KA: The Christian Armenian community in Qamishli and Aleppo was quite content with Assad. He largely didn’t bother them; they did various forms of ass-kissing that many do to survive under brutal dictatorship. But unlike the Islamized Armenians, who were marginalized and invisible, Christian Armenians had access to cultural institutions like the church, they had schools. That fostered a stable but regime-dependent identity. They weren’t happy with the revolution and the establishment of the Autonomous Administration. Christian Armenians perceive it as Kurdish rule, despite its multi-ethnic framework, and they are slightly resentful, even as overall there aren’t too many problems.

I want to give an example of their relations through a story I know happened. In Qamishli, there was a small Armenian office, a small local initiative. This office apparently had a framed portrait of Assad on the wall. And Kurds from the Administration had to sort out some unrelated issue with them, but they refused to enter that office as long as that portrait of Assad was hanging on the wall. So these Kurds from the Administration called a key Armenian figure who is quite high up and influential in Kurdish circles—he’s an old-guard PKK-aligned former fighter, well-respected—to mediate.

He told me this story laughing; he thought it was so funny. He went to the Armenians and was like, Guys, just take the portrait down, and they did. I don’t think they cared about it, it was just this performative gesture they had done years before and forgotten about. As soon as they took it down the Kurds entered and they were able to solve the problem.

On the flipside there was another incident where the Autonomous Administration was pressuring the Armenian school that’s attached to the church to adopt its new curriculum—the church was still using the Baathist curriculum. Because of this pressure, the church was resisting; there was an impasse. So the church approached that same individual to see what he could do, and this time the man decided that it was too much trouble to impose this new curriculum at the time, so he spoke to the Kurds: Just lay off temporarily. They’ll change it eventually, maybe it’s just a little too soon. So they did.

That’s just to give you an idea of the way these social networks and conflict resolution work. Going back to the Christian Armenian community and its resentment of Kurdish rule: there’s such a huge disconnect here. When I went to speak with the priest—that whole exchange is in the article; it wasn’t fun. He basically berated me for an hour. He was angry, essentially, that I’d been speaking to these Islamized Armenians. You don’t understand! This isn’t America, this isn’t Armenia! This is Syria, we need to be careful! And he was telling me the Islamized Armenians were making public statements against al-Sharaa, calling him Daesh, rejecting his rule. He told me they have no right to speak on behalf of Armenians—They’re not Armenian anyway—and they’re also spreading dangerous rhetoric.

He was trying to drive home this point that We as a community have to tread carefully, or we’ll end up like the Alawites. With a triumphant smile, he said, I sent a message to Damascus—really self-satisfied—and I heard that my message went to the very top, to al-Sharaa himself. Simultaneously, if you ask Armenians, even in the most conservative Christian, formerly pro-Assad neighborhoods, whether they’d rather live under this new transitional government in Damascus or “the Kurds,” they unanimously say the Kurds. They are so afraid of what they perceive al-Sharaa to represent.

This shift in their attitude to some degree represents the Autonomous Administration’s success in governance, and in particular in ensuring security for the region. That’s the biggest issue for everyone in general in Syria, but in the Autonomous Administration they look at the unrest and the lack of stable security in the rest of Syria, and they think, We don’t want that.

That is at odds with what the church is doing. The Armenian church is doing what the church has traditionally done: cautious, ingratiating behavior to whoever is in power. It was Assad before, now it’s al-Sharaa—Whatever! Partly it’s the “minority” thing to do, but also it’s in some part due to the legacy of genocide. You have to play nice, you have to be the good community that plays along, don’t stick your neck out so we don’t get killed.

LS: And of course the Kurds participated, to some extent, in the Armenian genocide. Do you think that’s a historical reason for this resentment towards Kurdish rule? And what steps is the Kurdish administration (or are Kurds in general) taking to recognize and address that role, and reconcile it?

KA: Definitely. Much of the resentment among Christian Armenians in Qamishli is due to the historic role of Kurds in the genocide, both as perpetrators and as directly benefiting from the stolen wealth.

Since that happened, Kurds themselves became targets of Turkish state aggression, and collectively—this is partly due to Abdullah Öcalan’s writing, owning up to his people’s role in the Armenian genocide and calling for more cooperative collaboration with Armenians in this brotherly framework—that attitude is more mainstream than you would think. There are still Kurdish nationalists who talk about the concept of “Kurdistan,” and a lot of Armenians look at that and say, That’s historic Armenia, that’s not Kurdistan, and so on. But in the Autonomous Administration in particular—much of this work, by the way, has been done by Kurds in Turkey, including the memory work. Particularly in Diyarbakır, which is a Kurdish-majority city where local Kurdish political figures have done a lot to connect with the Armenian community and support them, going so far as to fund the reconstruction and restoration of old Armenian monasteries in the city and inviting Armenian delegations from abroad to come and participate in mass.

It’s hard to imagine that happening now; that window is closed to a large extent. But in the Autonomous Administration it’s almost baked in. Because it’s a multi-ethnic, multi-confessional society where every group has the right to its own institutions and asserting its own identity, it’s already there. But I thought it was quite touching that personally, I was being taken around by Armenians to meet different party officials and Kurdish defense figures, and every time it was communicated to them that I was Armenian and coming from Armenia, it always felt genuine that they were grateful I was there. They would express their gratitude and sometimes apologize for their role in the genocide and express hope that we can work together moving forward in pursuit of common goals.

Also, at the Armenian genocide commemoration I attended in Hasakah, they had representatives of different communities come and speak—Kurdish, Arab, Yezidi—and all were reinforcing the importance of genocide recognition and working together against the common threat of Turkey, just to the north.

I live in Armenia, and if you speak to a random Armenian on the street and mention the Kurds, my expectation would be maybe six times out of ten they would express a negative opinion based on that history. But that’s largely because Armenians in the Republic of Armenia have not connected with the more recent memory work and acknowledgment of the Kurdish movement that’s been happening in the last couple decades. They don’t have access to that, they’re not connecting with it, so they don’t know. The predominant assumption is like, Oh yeah, those Kurds who killed us.

LS: It’s interesting, because you were in Syria at the same time as me, at the time just after the horrific massacres on the coast which had targeted the Alawi community. What was the feeling there at that time? There are so many minorities living in the northeast of Syria. How do they feel towards the future? Do they feel secure, or threatened? Could you give us a bit of insight into their reactions?

KA: “Concern” is probably the word I would use. Some worried more than others. A Christian Armenian in Qamishli told me—Armenians are already leaving. And she said, Armenians who aren’t leaving—don’t think they don’t want to leave. If they’re not leaving it’s because they don’t have the means. Others said, pointing to that violence on the coast, We’re next. This Autonomous Administration is the only thing standing between us and that kind of violence.

Sometimes I don’t know how much of this is personal conviction and how much of it is the political environment and political education they’ve all been undergoing, but someone was mentioning the long-ago departure of Jewish Syrians, particularly from their region, and saying, A loss of one group is a loss for all of us—again seeing themselves not as Armenians, post-Rojava revolution, but saying, It didn’t really matter; we never looked at who’s Kurdish, who’s Arab, who’s Armenian, because it didn’t really matter. But it’s this worrying concern that this project is under threat and they might have to be reckoning with a completely different system.

LS: Understandable. What do you think people’s hopes for the future are? What do they want to see going forward?

KA: On the one hand, their main concern is the security situation, and they do feel safer under the Autonomous Administration. But any time the conversation goes to the potential future of living under a unified, integrated Syrian state, they would enjoy the privileges of that. There are some issues with resources, with passports, since Assad fell and the lack of agreement over certain key areas. For example, a woman told me her eldest daughter was supposed to go to university this year, but Damascus wasn’t accepting university applications from the Autonomous Administration until some agreement was going to be reached. She had a lot of anxiety around her daughter missing a year, and just hoped something would be worked out.

This is being in a denied context and having to deal with all the deprivations that come with that. I haven’t been to the rest of Syria, I don’t know economically how it would compare. It’s probably quite different. Damascus and Aleppo, not having been there, seem much more cosmopolitan old cities, whereas there is no equivalent in the Autonomous Administration. Qamishli is the “big city,” and it’s a very provincial town.

But that’s it, that’s what they have.

LS: I think Idlib has taken over as the economic center of Syria now. Many people from Damascus go to visit these large malls in Idlib that they just don’t have there.

You spoke earlier about how people were desperate to make connections with Armenians outside of the Autonomous Administration. Do you have ideas how people can make those cross-border connections?

KA: There is the Armenian Social Council; they have a Facebook page, which is in Arabic. Although it’s not the easiest option, they can also travel to the region. It is possible, and as long as you have a translator for Arabic or Kurdish, you should be fine. Seeking these people out can be really rewarding, because they are so ready to connect.

More than anything they want to connect with other Armenians, but really anyone, not just Armenians: people who are interested in their experience who want to talk to them and learn from the way they’ve been able to survive physical death against all odds, and near total erasure of their identity. To have this unique opportunity at this time and begin to establish themselves and reclaim their identity—that in itself is such a remarkable story that anyone interested in social movements, mobilization, nationalism studies (it doesn’t need to be scholarly), I would definitely encourage people to go and connect with them.

Because this community is so new, any connections with them would help them establish themselves further. That recognition from the outside is something they desperately want, and that they are being denied by their own people in large part. But this administration is opening opportunity for them to assert their identity and meet other people, especially from the outside, on their own terms as Islamized Armenians.

LS: One final question I have for you before we wrap up is: have you published your research in Armenia and been talking to Armenian media? What was the reaction?

KA: It was a really interesting reaction. I’ve published one interview in an Armenia-based TV news organization, and an article in a US-based Armenian diaspora publication. Reactions to them have been really something.

As a friend noted, the comments under the article are very long, paragraphs long. They’ve clearly elicited an emotional response. Comments under the YouTube interview are maybe not as long, but they are similarly touched: many Armenians, even Armenians from Syria, are saying, We’ve never heard of this community before, and connecting certain issues they are familiar with—for example the church being conservative and rigid and exclusionary in the way it deals with the community. Lots of people are saying, It doesn’t matter what religion you are, you can be Armenian no matter what, and The church is super corrupt and we don’t like the church!

Someone who described herself as half-Kurdish and half-Armenian—this was the most remarkable comment I’d seen under this. She’s Armenian on both sides of her family; she grew up in Turkey and the only way they were able to find out was certain echoes and hints from elders. When they went into the records, they were told they had been burned, they were completely gone. But they had adopted Islam also, to survive. She was saying, almost as a response to some of the comments (there were some skeptical ones: You’re not really Armenian if you’re not Christian): Life goes on, life has to go on.

In her family’s case, she said the adoption of Islam was so superficial that Christian or atheist, agnostic practices continued in the home, to the point that she said, If you asked my parents what are the five pillars of Islam, they would have said, “What?” It’s just a coat that you put on to survive. Now she tells people that she’s half-Kurdish half-Armenian, even though she’s fully Armenian, because she grew up in the Kurdish community, when Kurdish identity is also being repressed in Turkey.

Now she says she lives abroad, and when she tells people she’s from Turkey, she says now she has to deal with the assumption on the other person’s part that she’s Turkish and Sunni, and that’s also an issue she has to deal with. So it’s just layers of identity and denial all stemming from this one really violent event.

LS: This has been a really fascinating conversation, Karena, thank you. It’s an issue I didn’t know about, and I’m sure a lot of our listeners wouldn’t have heard about it before.

KA: Thank you so much, Leila.