Transcribed from the 30 May 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

“These cases around women actually broaden our understanding of just how at risk black bodies are, and just how deep police authority has grown.”

Chuck Mertz: It’s not only black men who are victims of violence at the hands of police. Black women have been killed by cops, too. You may not know their names like you know Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, and Eric Garner. Maybe that’s the problem.

Here to tell us about the black women victims of police brutality and the #SayHerName campaign is Kimberlé Crenshaw, co-author of the report #SayHerName: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women, a document highlighting stories of black women who have been killed by police and shining a light on other forms of police brutality often experienced by women, such as sexual assault.

How are you, Kimberlé?

Kimberlé Crenshaw: I’m doing well, thank you for having me.

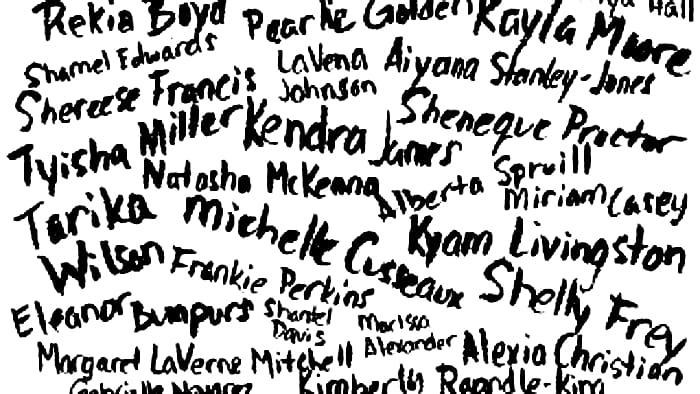

CM: It’s great to have you on the show. Let’s just start at the beginning: there was a major protest across the country on May 21st. As The Nation reports, “rallies and vigils in more than 20 cities including Baltimore, Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles demanded that onlookers, the media, and the public at large #SayHerName. Participants argued that a truly inclusive movement challenging police misconduct and state violence would make sure the names of Tanisha Anderson, Michelle Cusseaux, and Tarika Wilson—all black women killed by police—are remembered and used as motivating rallying cries alongside the names of their male counterparts.”

I saw some—but very, very little—news coverage of this. Did you see much? Or is the media still ignoring even the movement to get people to stop ignoring black women victims of police violence?

KC: You put your finger right on the problem. Within the non-traditional media, there was some coverage. But in terms of the major newspapers and the dominant electronic media, no, there wasn’t a lot of coverage of the protest.

There was a lot of conversation about it online. The internet blew up, particularly when the sisters protesting in the Bay Area bared their breasts, which is a traditional way of symbolizing outrage in African society. That got some coverage. And there was an article in the Washington Post that covered the report. But broadly speaking, it was once again the same kind of white-out, the exact issue we had been protesting. So it was very disappointing.

I would add to that that there are many commentators and op-ed columnists who we are accustomed to seeing picking up issues about police brutality against black men, and they too seem not to have been moved to speak on this issue. So it’s an ongoing struggle.

CM: What does it say about sexism or the state of our media when one of the few instances of these rallies getting any kind of media attention was when women exposed their breasts?

KC: It tells us a couple things that are also at the core of our report. Black women don’t come into view as victims of police brutality; they’re not seen as representative of how the entire community experiences racism. Nor do they come into view when the conversation is about violence against women, which of course police violence against black women is. So it’s a two-level problem. When it’s about women, black women and other women of color are rarely seen as emblematic of the issues that women face; similarly, issues that are typically framed around racism are rarely, if ever, framed around how black women experience racism.

It’s a two-level problem in another sense as well. Structures of inequality create particular kinds of risks that black women face—that’s the first level of discrimination. The second level is that things that happen to them are largely irrelevant in the media, in policy debates—and often they are even marginalized within anti-racist movements. This is what this entire #SayHerName campaign is trying to resist and operate against.

CM: There is this sexist idea that we often see the media embrace: they’ll cover stories when the narrative is a kind of “damsel in distress” situation, one about “protecting” women. So why don’t stories of black women abused by police get on the air? Why doesn’t it fulfill the “damsel in distress” narrative that we often see the media embrace?

KC: Well, they’re not given the “benefit” of being the damsel in distress because they’re black. There are particular ways of being a woman that puts you outside of even the sexist stereotypes about police coming to the rescue of women. In fact, several of the cases that we talk about in the report involve the police being called to give assistance. They could be typical “damsel in distress” situations. But when the police show up and the damsel is a black woman, she winds up being killed.

Tanisha Anderson was killed about ten days before Tamir Rice by the Cleveland police. Her family had called an ambulance because she was having a mental health crisis. Instead, the police showed up. And they saw this as a contain, constrain, and control situation, not that this person is in distress and needs sensitive intervention.

They attempted to force her into a car; they separated her from her family—which, as everyone with any knowledge of mental health issues knows, is the last thing you would do with a person in crisis. She did not want to get into the car. They performed a body slam on her, and knelt into her back, and she eventually stopped breathing. They disallowed the family from even approaching to comfort her as she lay out on the street, dying, barely clothed, in the snow, in Cleveland.

This is an unfortunate episode, but it’s not unusual. Other such cases—Michelle Cusseaux and Kayla Moore are two more examples—began when someone called the police to help the women. Instead, each of these women ended up being killed. This is a classic situation where black women are seen as targets of intervention and constraint rather than people to be helped, and therefore they end up dead.

CM: Black Youth Project had this announcement of last week’s rallies at their site: “Recent events across the country have demonstrated that police murders, sexual assault, and harassment continue with impunity. As we struggle to fight for justice for loved ones like Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, and Rashad McIntosh, we cannot forget and must fight fiercely for Mya Hall, Aiyana Jones, and Rekia Boyd. The police harass, abuse, murder, and do not discriminate based on gender or sexuality.”

I do not see stories of sexual assault by police in the news. I see stories of police violence in the news, but not sexual assault. Are there stories about police sexual assault?

KC: This is one of the reasons our report is framed in two different ways. One is to lift up the names of women who were killed by police in ways parallel to the way that men are killed. There are these common frames that help us understand what police brutality looks like. Many of the stories in the report were stories that said, look, black women are invisible not because they don’t experience these things. They experience some of the exact same things.

But killing is not the only way that black women experience police violence. What happens to black women when they encounter the police? Yes, they are killed; yes, they are beaten, like Marlene Pinnock on the side of the highway by California Highway Patrol—but they are also disproportionately subject to sexual violence.

Daniel Holtzclaw, for example, was finally charged with raping thirteen African-American women. How is it that this officer could have gotten away with thirteen sexual assaults? It gives us a window to the vulnerability that African-American women face more generally. When African-American women charge someone with rape, they’re least likely to have their cases prosecuted. And even on the rare occasion where their cases are prosecuted, those who are convicted of raping them receive the lowest penalties of all people who rape women.

And this doesn’t even account for police sexual violence, which studies have suggested is a highly significant issue. The fact that we don’t hear about it doesn’t suggest that it doesn’t happen. It suggests that the people who it happens to don’t matter. People don’t believe them.

CM: You report on half a dozen pregnant women and women with children present who were killed or subjected to excessive force by police. You include the story of Rosan Miller, who was put in a possibly prohibited chokehold by the New York police while seven months pregnant. This encounter started because Ms. Miller was grilling on the sidewalk.

What proportion of cases of police violence against black women are started over misdemeanors? We recently had author Scott Jacques on the show, who wrote about drug-dealing in Code of the Suburbs, and he talked about the shortcomings of police in inner city areas when it comes to responding to crime and enforcing law. I’m starting to get the feeling that real crime isn’t fought in poor neighborhoods, but misdemeanors are.

“There were others who said this was not the place for it. ‘Where are the men?’ they would ask us.

…The men are on all of the other posters.”

KC: Yes, that’s right. But I have to say that one of the challenges across the board is that reliable data is often difficult to find. With respect to killing, as many commentators have pointed out, there is no federal requirement that local municipalities track that data and report it. One of the main recommendations to come out of the Obama Administration’s 21st Century Policing Report is to start doing that.

But from the cases that we collected—either from personal knowledge (my co-author Andrea does a lot of work in this field), or in the newspapers and on the internet—we found that most of the women who suffered a violation of some sort did fall within the “Broken Windows” policing approach that focuses a lot of attention and enforcement on misdemeanors and minor infractions.

We’ve talked a lot about Broken Windows policing as one of the reasons behind the Stop-and-Frisk policy in New York, which grew into such an unconstitutional problem that a court prohibited the police department from continuing it. What we talk less about is that black women have the same disproportionate incidence of being stopped and frisked as black men do. It is not just a male problem.

We also don’t talk about the other ways that this kind of surveillance impacts the everyday lives of black people, particularly women. It wasn’t just that the police think you look suspicious when you’re out and about. If you’re in front of your own house trying to grill, that is apparently also an occasion for the police to intervene.

The police are given carte blanche to engage in surveillance and excessive intervention in the movement of people through public space. But moreover, cases involving women actually involve police coming into their homes and engaging them there. Kayla Moore, for example, was killed in her own bedroom. This is a particularly gruesome aspect of being subject to police abuse. If you can’t control how you move or if you look “furtive” or not (as we saw in the conversation around the killing of Trayvon Martin—why was he wearing a hoodie?), you certainly can’t perform your way out of the risk of being killed by police when you’re in your own home, in your own bedroom.

These cases around women actually broaden our understanding of just how at risk black bodies are, and just how deep police authority has grown—into the capacity, through Broken Windows policing, to intervene in social contexts with a criminalizing, coercive intervention practice that often leaves black people dead.

CM: Here’s Dani McClain writing at The Nation last week: “There’s also the case of Dannette Daniels, a 31-year-old pregnant woman who was fatally shot in the head by a Newark, New Jersey, police officer in 1997. The officer was later cleared of criminal charges. To be fair, hundreds of people marched to protest the shooting at the time. But Daniels’ name is rarely if ever heard among those of others brutalized or killed by police during that same time period, such as Anthony Baez, Abner Louima, and Amadou Diallo.”

How much can we blame activists who fight against police violence for this lack of attention being given to black women victims of police violence?

KC: I think it’s important to recognize that there are activists across the spectrum who have very different orientations regarding the importance of incorporating patriarchy inside the demands of an anti-racist struggle. You mentioned Black Youth Project; Charlene Carruthers is one of the leading young women who are insisting that gender identity and sexuality be incorporated inside the movement against racism.

At the same time, there are both traditional leaders and younger leaders who don’t see these issues as being intersectional. They don’t necessarily remember the additional ways that black women—cis black women and transgender black women and queer black women—are also made vulnerable.

A case in point: we came up with the #SayHerName hashtag during the Eric Garner demonstrations in New York; we had pulled together a banner that had several images of black women who had been killed by police. Some people were very supportive of the idea of talking about women as well in this campaign. Others were just stunned. They had no idea that black women were also killed by police—understandably, because it’s not talked about. But then there were others who said this was not the place for it. “Where are the men?” they would ask us.

The men are on all of the other posters. This is the one banner that had women who were killed by the police. It’s not surprising that in the racial justice movement there are some who have male-centric views. We live in a male-centric society, so it’s not surprising that it’s replicated in some ways in our movement. What’s really promising about today, though, is that so many women in the movement are in leadership positions, and they are bringing this conversation to the forefront.

So yes, it is a struggle. And yes, we can say that we bear some of the responsibility for the erasure of black women. So it’s our responsibility to lift up those who are now lifting up these cases in the racial justice movement.

CM: At the Black Youth Project 100 website, it states: “All #BlackLivesMatter, and that means we uplift and fight for lasting justice for the families of victims of police violence. We’ve joined Ferguson Action and Black Lives Matter to put out a national call for actions to end state violence against all black women and girls.” This is all part of the #SayHerName campaign.

How would you describe the impact that a combined effort by Ferguson Action, Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project 100, and #SayHerName would have on civil rights and civil rights activism here in the US?

KC: I think we’re looking at the face of the new generation of racial justice activism. Of course, these questions are not new. And black women have been at the forefront of organizing around racial justice all along, and at key moments in time, gender has played a significant role. That has just been largely forgotten.

So this is an exciting moment, when young leadership has made the call for women to be at the center and to bring the lives and the names of women into the center of the advocacy. Our hope has to be that there is broad-scale pickup, that there is insistence that these names not be forgotten. The simple beauty of #SayHerName is that it is an action that can be done individually and collectively.

It’s a very hopeful moment, and the call that the Black Youth Project 100 put out was answered by so many people around the country. The hashtag was a useful vehicle for bringing a lot of that energy forward. This is the best kind of coalition possible, and it’s a very exciting time.

“Our modern police are simply the contemporary version of slave patrols, of the cavalry, of all the ways that the state used the police to enforce racial stratification and hierarchy.”

CM: Your report offers some examples of gender-specific and inclusive policy demands to address black women’s experiences of policing. One of these is the call for a comprehensive ban on the use of the mere possession or presence of condoms as evidence of a prostitution-related offense.

Is that seriously allowed? Is this a way that police harass black women on a regular basis?

KC: Particularly poor black women, transgender black women, homeless black women, black youth. One of the key aspects of policing that Andrea Ritchie speaks to is the way that the police are deployed not just to police “broken windows” but actually to police gender and gender performance, to police bodies that don’t fall into categories that the police see as legitimate—and to suspect, whenever they see a black woman or a transgender woman in a particular space or dressed in a particular way, that there is something afoot that they are empowered to step in and police.

Many of the black women who come into the criminal justice system have encountered police who think that it’s their role to engage in gender and sexuality policing.

So some of these recommendations come particularly from the practice of defending marginalized women from the ways they, specifically, are at risk of encounters with the police. When we broaden the frame of “policing,” we see a whole new template, a whole new terrain of vulnerability that creates the need for different kinds of policy interventions.

We’re not going to get to this if the only thing we think the police are doing is harassing black men while they’re driving or walking.

CM: Another one of the many suggestions you have that I wanted to mention is calling for use-of-force policies clearly prohibiting the use of tasers and excessive force on pregnant women or children.

So you’re currently allowed to taser kids and pregnant women?

KC: Currently, the approach to excessive force is that it is essentially a subjective determination by the police officer. If the police officer says that in his or her judgment, or at the time, they felt that they were in significant risk of serious bodily harm, in some jurisdictions, tasering can be used to effectuate control over the subject. So if the subject is not “in control,” tasering is sometimes allowed.

There’s a case ongoing right now with a black woman, Natasha McKenna, who was killed in Virginia by being effectively tasered to death as police were trying to extract her from a cell. Hopefully that’s going to be a case that people will follow. What made those officers think that it was okay to taser her? The rules themselves are permissive, based on the officers’ interpretation of what the situation is, and only very rarely will a judge or a jury say that it was unreasonable under the circumstances.

I’ll broaden it just to point out that in the acquittal of the officer who killed Malissa Williams along with her partner by jumping on the hood of her car and shooting them to death, the judge said that his fear was “reasonable.” This is a man who jumped on the hood of the car, saying that he wasn’t sure whether they were shooting. If that can be seen as a reasonable use of force, then the use of tasering is also going to be difficult to confine.

CM: We have one last question for you, Kimberlé, and it’s what we call the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience might hate your response.

If we are trying to be inclusive, recognizing police violence versus black women as well as versus black men, doesn’t this need to be a movement without the racial factor? In other words, does Black Lives Matter need white people to be recognized as victims too in order for state violence across the board to be changed? What I’m asking is (and this is the worst possible way to phrase it): do white lives have to matter before black lives will?

KC: That’s an excellent question, but I wouldn’t say it’s from hell. In fact I would say it’s from heaven. I’ll put it this way: in the kingdom of heaven, when white people and black people are treated exactly the same, then absolutely, it makes total sense that any problem be articulated in the most race-neutral way possible.

But we live on the planet Earth, and more importantly we live in the United States of America, where the entire project of policing is based on our history of creating a racialized democracy. Our modern police are simply the contemporary version of slave patrols, of the cavalry, of all the ways that the state used the police to enforce racial stratification and hierarchy.

Does that mean that white people aren’t impacted? Of course not. And it also doesn’t mean that white people don’t matter. White people matter in the same way they mattered in the civil rights movement. White people were absolutely essential in saying, “This is not the democracy I want to live in. Even though I might not be at risk in the same way as this black body, I am at risk living in a society where anyone is allowed to be treated this way. I know that if any of us is subject to this, all of us can be subject to it.”

Yes, white people are significant. Yes, this movement depends on white people recognizing that the police need to be constrained. And yes, we believe we can get there with a focus on black lives mattering.

CM: Kimberlé, thank you so much for being on This is Hell! with us today.

KC: Thank you for having me. It was a pleasure.