AntiNote: The following article, written almost exactly two years ago, has special significance to us for several reasons, primary among them of course the subject matter—the gas attack in the outskirts of Damascus whose second anniversary was just observed by Syrian liberation activists and allies around the world—and the author.

Razan Zeitouneh is an award-winning Syrian human rights lawyer and activist who was abducted along with her spouse and two colleagues just a few months after writing this heartbreaking eyewitness account of the Ghouta massacre. Her story is one that should be far more widely known, and provides a glimpse of the shape that the civil society movement took (though the assumption is widespread that it disappeared completely) after the Assad regime decided to counter the uprisings of 2011 with barbarous violence. Efforts to find her and secure her release have not ended.

Resources in English about the movement of which Razan Zeitouneh was a part and the context in which she worked are relatively rare but not inexistent. A good place to start is a medium-length documentary in Spanish and Arabic (with English subtitles), Ecos del Desgarro, which we recently shared in the Cinema Utopia section of this site.

A Search For Loved Ones Among Mass Graves

by Razan Zeitouneh

Originally appeared at Now. Media on 23 August 2013 (site no longer live)

“We have grown accustomed to the fact that anything is possible in this war and that the sole means to confront it is to prepare for anything.”

East Ghouta, Syria

I am trying to replay that day in slow motion in the hope of bursting into tears as any “normal” person is supposed to do. I am terrified by this numbness in my chest and the fuzziness of images running around in my mind. This is no normal reaction after a long day of tripping on bodies lined up side-by-side in long and dark hallways. Bodies are shrouded in white linen, and old blankets show only faces that have turned blue, dried foam edging their mouths, and sometimes, a string of blood that mixes with the foam. Foreheads or shrouds bear a number, a name, or the word “unknown.”

The same stories and images are repeated across each medical outpost in Ghouta towns, which welcomes those martyred and wounded. Medics, the majority of whom have been affected by the poisonous gases, tell over and over again how they yanked doors open and entered houses where they found children sleeping quietly and peacefully in their beds. A few reached medical outposts and benefited from first aid. But the most pressing image is that of whole families dead: a father, a mother, and all of their children who were taken from their beds straight to mass graves.

A father is standing by a seemingly endless long grave in Zamalka, where his wife and child are buried by the side of numerous other families. I thought he must be secretly envying the families whose members all went to these narrow graves, leaving behind no one to feel the pangs of loss.

Clashes are still heavy and near, but no one cares. Everyone is busy digging and sprinkling dirt over loved ones. One person overseeing the burial operation explains how 140 bodies are put side-by-side in this little grave.

Take pictures, he says, before listing the names of whole families buried here and there. We wait as if we are supposed to meet the family, greet the parents, and play with the children; but all we see is some uneven dirt and a few twigs scattered randomly over it.

Families flock to search for their children in hallways lined with bodies in each town. An old lady comes in, imploring those present to lead her to the bodies of her sons and brethren if they have been martyred. Young men help her to lift covers off the faces of unknown martyrs waiting for someone to identify them. She goes from one face to another, gasping at one point when mistakenly seeing a face she thought she knew. The search ends and she starts praising Allah in her quavering voice as the odds of one of her loved ones being dead is now smaller after inspecting one medical outpost.

In most cases, families were scattered over medical outposts throughout Ghouta. Those who were treated and regained their strength begin the journey of looking for family members from one town to another. And for those people who did not find their loved ones in hallways lined with the wounded or martyred, or among the list of deceased that administrative staff managed to record, most could barely control their anger and sadness – often collapsing in tears as a result.

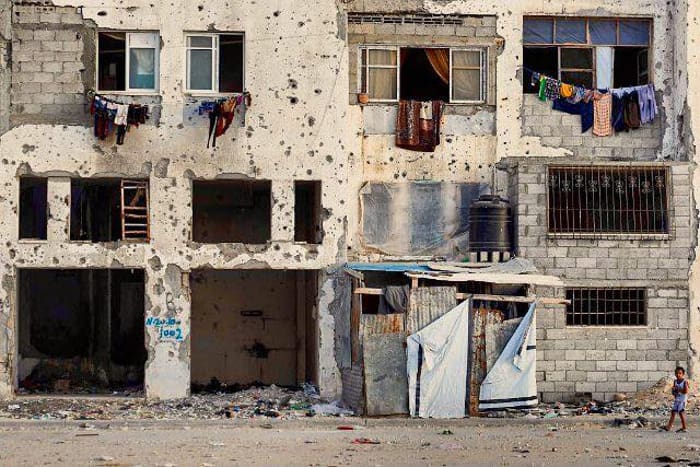

Those wounded are not faring much better, especially the children. Many children sob when anyone tries to speak with them, and the children ask where their parents are, but nobody has answers. In any case, people in East Ghouta cannot come to terms with what happened. This is a country filled with uncertainty, but even these events should not happen.

A man stands next to a medical outpost, crying and wringing his hands. He said he saved three women and drove them to the hospital. But he was in such a hurry that he ran over someone and killed a man on the way. As he parked his minivan in front of the hospital and tried to decide on what to do about the man he ran over, a MiG jet chose this particular spot to launch an airstrike merely minutes later that annihilated the minivan. Who would go through such events within a matter of hours and still believe that Judgment Day is not near?

Even those who are still holding on to some remnants of strength burst out in anger. No one can fathom that hundreds of martyrs could have been saved had there been more medication or had donors decided to provide aid to medical outposts specializing in chemical attacks. Even doctors are angry at themselves for having to choose between one wounded and another, and playing a lottery of life and death in revolutionary Syria. One doctor named Majed wrote on Facebook: “I cried and I cried all day long as I was receiving the donations of generous people who were not convinced that the project we submitted four months ago to equip a medical outpost to deal with chemical attacks is a necessity. Hundreds of martyrs now convinced them of it… I cried while signing my approval to cash in these sums, the price of which has been paid in the pictures of martyrs…”

But the problem is much graver: We have grown accustomed to the fact that anything is possible in this war and that the sole means to confront it is to prepare for anything – there is nothing more we can do.

When fathers and mothers speak to their children, it’s all the more self-evident. ‘My son, brush your teeth and go to bed, it’s already late. Don’t drink too much water before bedtime. If you hear the rumbling of a plane, go down to the basement. If you smell something foul, climb up to the roof. If you run out of time to do any of the above, just know that I love you but there is nothing I can do. The world is a filthy and cruel place. One day you will understand that if you get the chance to grow up.’

‘Bid goodnight to your country, my son.’

This article is a translation of the original Arabic, also published by Now.Media.

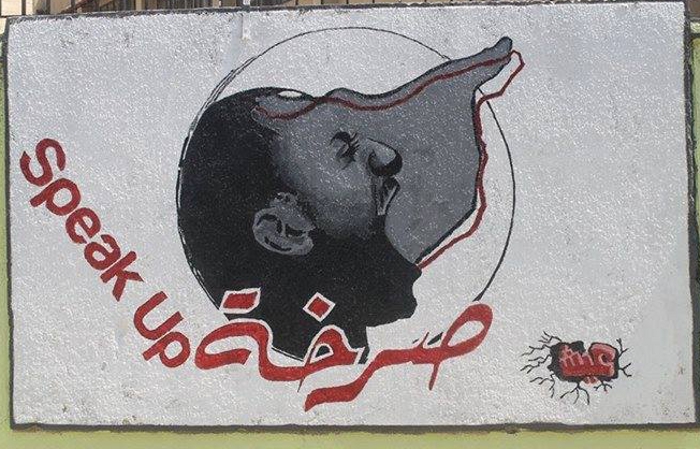

Featured image: public art in Kafranbel, Syria. Source: Dawlaty.org (Facebook)